Medicare spends huge sums financing the dental, vision and other benefits offered by Medicare Advantage plans. A new government report sounds the alert about their potential misuse.

In mid-March, the Medicare Payments Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which advises Congress on Medicare policy, made a bombshell disclosure in its annual Medicare report. The rebates that Medicare offers Medicare Advantage plans for supplemental benefits like vision, dental, and gym membership were at “nearly record levels”, more than doubling from 2018 to nearly $64 billion in 2024, but the government “does not have reliable information about enrollees’ actual use of these benefits at this time.”

In other words: $64 billion is being spent to subsidize private Medicare Advantage plans to provide benefits that are not available to enrollees in traditional Medicare, and the government has no idea how they are being spent.

Not only is this an enormous potential misallocation of taxpayer resources from the Medicare trust fund, it is also a critical part of Medicare Advantage’s marketing scam. The additional benefits offered in Medicare Advantage plans are what entice people to give up traditional Medicare, where there is no prior authorization, closed networks, or care denials.

But, as MedPAC states in the report, even though the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) does not collect the data on utilization of supplemental benefits, what little data there is does not paint a pretty picture, with MedPAC noting that, “Limited data suggest that use of non-Medicare-covered supplemental benefits is low.”

HEALTH CARE un-covered is among the first media outlet to report MedPAC’s findings.

A 2018 study by Milliman, an actuarial firm, found that just 11 percent of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had claims for dental care in that year, and that “multiple studies using survey data have found that beneficiaries with dental coverage in MA are not more likely to receive dental services than other Medicare beneficiaries.” A study from the Consumer Healthcare Products Association found that just one-third of eligible participants in Medicare Advantage plans used an over-the-counter medication benefit at pharmacies, leaving $5 billion annually on the table for insurers to pocket. Elevance Health, formerly Anthem, has 42 supplemental benefits available to Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. They analyzed a subset of 860,000 beneficiaries. For six of the 42 benefits, the $124 billion insurer could not report utilization data. For the other 36 supplemental benefits, the bulk of those covered used fewer than four benefits, with a full quarter not using any benefits at all and a majority using one or less benefits.

Medpac added that it had “previously reported that while these benefits often include coverage for vision, hearing, or dental services, the non-Medicare supplemental benefits are not necessarily tailored toward populations that have the greatest social or medical needs. The lack of information about enrollees’ use of supplemental benefits makes it difficult to determine whether the benefits improve beneficiaries’ health.”

With studies already showing that Medicare Advantage is associated with increased racial disparities in seniors’ health care, the massive subsidies provided to supplemental benefits appears to be an inadvertent driver of this problem:

the $64 billion—at least the portion of it that is actually being spent as opposed to deposited into insurer coffers—is likely not going to the populations that actually need it.

Amber Christ is the managing director of health policy for Justice in Aging, which advocates for the rights of seniors. “Health plans are receiving a large amount of dollars to provide supplemental benefits through rebates to plans. Clearly the offering have expanded, but the extent that they are being used is a black box,” she said. What little we do know, she said, indicates a “real lack of utilization.”

Christ pointed out that the Biden administration has taken some significant steps forward. “We’ve seen some good things coming out of CMS that will bring some transparency—the plans are going to have to report spending and utilization data, and in 2026 they will have to start sending notices to enrollees at the six-month point, letting people know what benefits they have used and what’s available. Those are all good moves.”

What’s missing from the proposed rule-making, however, is how the colossal outlays to supplemental benefits impact the goal of health equity, Christ said. “What we would have wanted to see more is demographics around utilization. Are there disparities in access?”

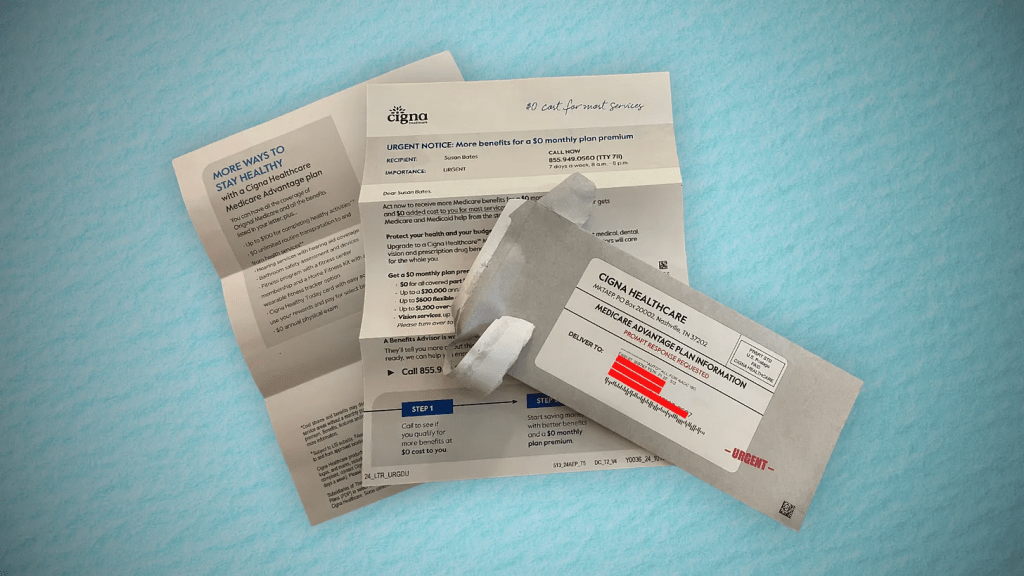

Of particular concern to advocates is the way that Medicare Advantage plans use supplemental benefits to market to “dual eligibles,” people who are eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have taken to offering what amounts to cash benefits to dual eligibles, which provides a very strong incentive for people to sign up for Medicare Advantage.

But it’s effectively a trap, as being in both Medicare Advantage and Medicaid can not only result in prior authorization, care denials, and losing access to one’s physician, but also making care endlessly complex.

“Medicaid offers a bunch of supplemental benefits, either fully or often more comprehensively than Medicare Advantage. Seniors get lured into these health plans for benefits that they already have access to. But because benefits between Medicare Advantage and Medicaid aren’t coordinated people experience disruptions to their access to care. If they are dually enrolled it should go above and beyond, not duplicate coverage or making it more difficult to access coverage,” Christ said.

David Lipschutz, the associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy, related an experience he had with a state health official who counseled a senior against enrolling in Medicare Advantage. The official “was able to stop them and help them think through their choices. She wanted to enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan that offered a flex benefit,” which is basically restricted cash (Aetna, for example, restricts its recipients to spending the money at stores owned by CVS Health, its parent company). “None of her five doctors contracted with the Medicare Advantage plan. Had it not been with that interaction with the health counselor. She would have traded the flex card for no access to her current physicians. It’s an untenable situation.”

Lipschutz added that Medicare Advantage insurers contract with community organizations to administer supplemental benefits, which helps to insulate the industry from political pressure from advocates in Washington. “This whole new range of supplemental benefits has also at the same time pulled in a lot of community based organizations. They need the cash that the plans are offering. It creates a welcome dynamic for insurance companies trying to make community organizations dependent on their money. But it’s not a good situation to be in when you’re trying to reign in Medicare Advantage overpayments.”

Bid/Ask

The core of the financing of supplemental benefits is through a bid system, in which CMS sets a benchmark based on area fee-for-service Medicare spending, and then invites insurers to submit a bid, and then receives a rebate for supplemental benefits based on the benchmark. The essential problem is that the average person in traditional Medicare is sicker than someone in a Medicare Advantage plan—the research shows that when patients get sick, they leave Medicare Advantage for traditional Medicare if they can. And Medicare Advantage plans aggressively market to healthier patients—the oft-touted gym membership supplemental benefit only works for those who actually work out at the gym regularly. (Well under one-third of those 75 and over.)

And in counties with low traditional Medicare spending, the benchmark is at 115 or 107.5 percent—an unreasonable and massive subsidy written into the Affordable Care Act at the behest of the insurance lobby. The lowest benchmark is at 95 percent of FFS spending for areas with high costs.

“The way the payment is set up leads to this excessive amount of rebate dollars,” said Lipschutz. “It’s a fundamentally flawed payment system which is in dire need of reform.” Lipschutz’s position jives with the MedPAC report, which states that: “A major overhaul of MA policies is urgently needed.”

Supplements For Half

“You shouldn’t have to enroll in a private plan just to access these benefits,” said Lipschutz. But that’s exactly the choice millions of seniors are faced with. Forty-nine percent of seniors remain in traditional Medicare.

And for that group, Medicare offers no supplemental benefits, Christ said. “As a foundational principle spending all this money for Medicare Advantage to give supplemental benefits doesn’t make sense. This is the Medicare trust fund. Half of Medicare has “access,” and the other half, in traditional Medicare, doesn’t. Wouldn’t those dollars be better spent giving everyone access? Especially when we understand that Medicare Advantage has narrower providers and prior authorization.

There’s a recognition that these supplemental benefits have positive impacts on quality of life, but we’re not offering it in traditional Medicare—even though Medicare Advantage is not doing a better job than traditional Medicare.”

House of Cards?

A new lawsuit, filed in April, could substantially impact the incentives that plans have to offer supplemental benefits. To manage costs, many Medicare Advantage plans have value-based care arrangements with providers—meaning that they share some of their revenues with hospitals and other health providers to ensure access to networks and to smooth costs out in the long run.

But as part of this arrangement, providers bear some of the costs of the plans—including the cost of supplemental benefits. Bridges Health Partners, which is a clinically integrated network of doctors and hospitals, sued Aetna to block the allocation of supplemental benefits to the expenses that they bear the cost of, due to a 20-fold increase in their costs.

Combined with the 2026 requirement from CMS that participants be informed as to what benefits they haven’t used, insurers’ ability to offer these supplemental benefits and still retain sky-high profit margins could be curtailed.