https://one.npr.org/?sharedMediaId=968920752:968920754

The Problem

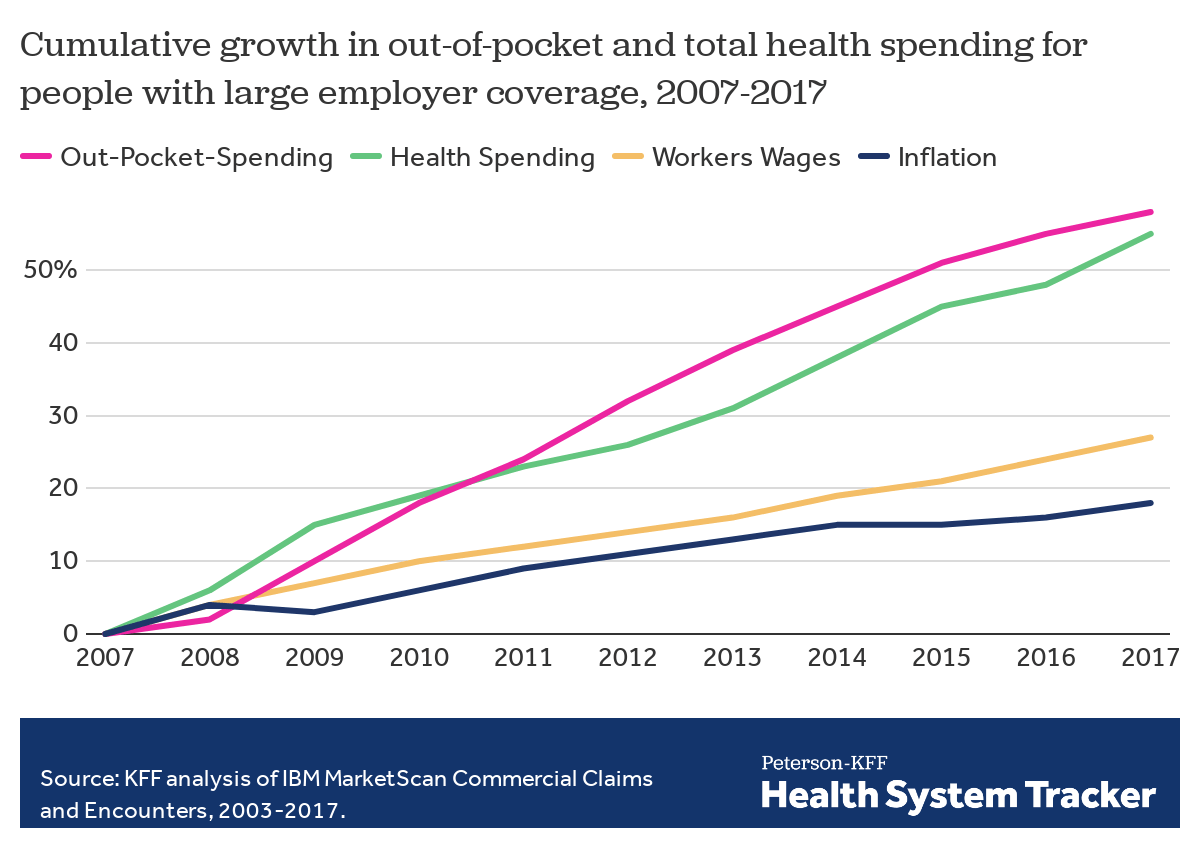

Employers — including companies, state governments and universities — purchase health care on behalf of roughly 150 million Americans. The cost of that care has continued to climb for both businesses and their workers.

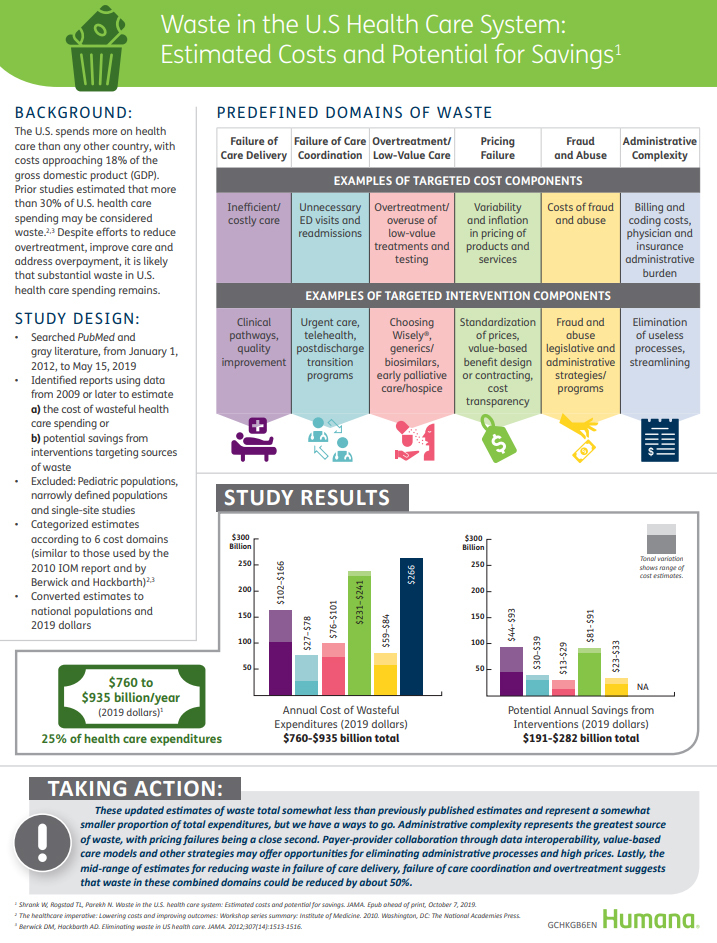

For many years, employers saw wasteful care as the primary driver of their rising costs. They made benefits changes like adding wellness programs and raising deductibles to reduce unnecessary care, but costs continued to rise. Now, driven by a combination of new research and changing market forces — especially hospital consolidation — more employers see prices as their primary problem.

The Evidence

The prices employers pay hospitals have risen rapidly over the last decade. Those hospitals provide inpatient care and increasingly, as a result of consolidation, outpatient care too. Together, inpatient and outpatient care account for roughly two-thirds of employers’ total spending per employee.

By amassing and analyzing employers’ claims data in innovative ways, academics and researchers at organizations like the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) and RAND have helped illuminate for employers two key truths about the hospital-based health care they purchase:

1) PRICES VARY WIDELY FOR THE SAME SERVICES

Data show that providers charge private payers very different prices for the exact same services — even within the same geographic area.

For example, HCCI found the price of a C-section delivery in the San Francisco Bay Area varies between hospitals by as much as:$24,107

Research also shows that facilities with higher prices do not necessarily provide higher quality care.

2) HOSPITALS CHARGE PRIVATE PAYERS MORE

Data show that hospitals charge employers and private insurers, on average, roughly twice what they charge Medicare for the exact same services. A recent RAND study analyzed more than 3,000 hospitals’ prices and found the most expensive facility in the country charged employers:4.1xMedicare

Hospitals claim this price difference is necessary because public payers like Medicare do not pay enough. However, there is a wide gap between the amount hospitals lose on Medicare (around -9% for inpatient care) and the amount more they charge employers compared to Medicare (200% or more).

Employer Efforts

A small but growing group of companies, public employers (like state governments and universities) and unions is using new data and tactics to tackle these high prices. (Learn more about who’s leading this work, how and why by listening to our full podcast episode in the player above.)

Note that the employers leading this charge tend to be large and self-funded, meaning they shoulder the risk for the insurance they provide employees, giving them extra flexibility and motivation to purchase health care differently. The approaches they are taking include:

Steering Employees

Some employers are implementing so-called tiered networks, where employees pay more if they want to continue seeing certain, more expensive providers. Others are trying to strongly steer employees to particular hospitals, sometimes know as centers of excellence, where employers have made special deals for particular services.

Purdue University, for example, covers travel and lodging and offers a $500 stipend to employees that get hip or knee replacements done at one Indiana hospital.

Negotiating New Deals

There is a movement among some employers to renegotiate hospital deals using Medicare rates as the baseline — since they are transparent and account for hospitals’ unique attributes like location and patient mix — as opposed to negotiating down from charges set by hospitals, which are seen by many as opaque and arbitrary. Other employers are pressuring their insurance carriers to renegotiate the contracts they have with hospitals.

In 2016, the Montana state employee health plan, led by Marilyn Bartlett, got all of the state’s hospitals to agree to a payment rate based on a multiple of Medicare. They saved more than $30 million in just three years. Bartlett is now advising other states trying to follow her playbook.

In 2020, several large Indiana employers urged insurance carrier Anthem to renegotiate their contract with Parkview Health, a hospital system RAND researchers identified as one of the most expensive in the country. After months of tense back-and-forth, the pair reached a five-year deal expected to save Anthem customers $700 million.

Legislating, Regulating, Litigating

Some employer coalitions are advocating for more intervention by policymakers to cap health care prices or at least make them more transparent. States like Colorado and Indiana have passed price transparency legislation, and new federal rules now require more hospital price transparency on a national level. Advocates expect strong industry opposition to stiffer measures, like price caps, which recently failed in the Montana legislature.

Other advocates are calling for more scrutiny by state and federal officials of hospital mergers and other anticompetitive practices. Some employers and unions have even resorted to suing hospitals like Sutter Health in California.

Employer Challenges

Employers face a few key barriers to purchasing health care in different and more efficient ways:

Provider Power

Hospitals tend to have much more market power than individual employers, and that power has grown in recent years, enabling them to raise prices. Even very large employers have geographically dispersed workforces, making it hard to exert much leverage over any given hospital. Some employers have tried forming purchasing coalitions to pool their buying power, but they face tricky organizational dynamics and laws that prohibit collusion.

Sophistication

Employers can attempt to lower prices by renegotiating contracts with hospitals or tailoring provider networks, but the work is complicated and rife with tradeoffs. Few employers are sophisticated enough, for example, to assess a provider’s quality or to structure hospital payments in new ways. Employers looking for insurers to help them have limited options, as that industry has also become highly consolidated.

Employee Blowback

Employers say they primarily provide benefits to recruit and retain happy and healthy employees. Many are reluctant to risk upsetting employees by cutting out expensive providers or redesigning benefits in other ways. A recent KFF survey found just 4% of employers had dropped a hospital in order to cut costs.

The Tradeoffs

Employers play a unique role in the United States health care system, and in the lives of the 150 million Americans who get insurance through work. For years, critics have questioned the wisdom of an employer-based health care system, and massive job losses created by the pandemic have reinforced those doubts for many.

Assuming employers do continue to purchase insurance on behalf of millions of Americans, though, focusing on lowering the prices they pay is one promising path to lowering total costs. However, as noted above, hospitals have expressed concern over the financial pressures they may face under these new deals. Complex benefit design strategies, like narrow or tiered networks, also run the risk of harming employees, who may make suboptimal choices or experience cost surprises. Finally, these strategies do not necessarily address other drivers of high costs including drug prices and wasteful care.