Cartoon – Employing People with Disabilities

Democrats rode a health care message to their Election Day takeover of the House. Now that the election is (mostly) over, how will they follow through on that campaign focus?

The party is still figuring out its next steps on health care, and Nancy Pelosi and her colleagues will have a lot of decisions to make and details to sort out. “The new House Democratic majority knows what it opposes. They want to stop any further efforts by Republicans or the Trump administration to roll back and undermine the Affordable Care Act or overhaul Medicaid and Medicare,” writes Dylan Scott at Vox. “But Democrats are less certain about an affirmative health care agenda.”

Some big-picture agenda items are clear, though. “The top priorities for Ms. Pelosi, the House Democratic leader, and her party’s new House majority include stabilizing the Affordable Care Act marketplace, controlling prescription drug prices and investigating Trump administration actions that undermine the health care law,” reports Robert Pear in The New York Times.

House Democrats also plan to vote early next year on plans to ensure patients with preexisting medical conditions are protected when shopping for insurance, Pear reports. And they’ll likely vote to join in the defense of the Affordable Care Act and its protections for those with pre-existing conditions against a legal challenge now before a Texas federal court.

Here are a few areas where House Democrats will likely look to exercise their newly won power.

Stabilizing Affordable Care Act markets: “I’m staying as speaker to protect the Affordable Care Act,” Pelosi said in an interview with CBS’s “Face the Nation,” calling that her “main issue.” And Vox’s Scott says that “a bill to stabilize the Obamacare insurance markets would be the obvious first item for the new Democratic majority’s agenda,” adding that a bill put forth by Reps. Richard Neal (MA), Frank Pallone (NJ) and Bobby Scott (VA) is the likely starting point. Democrats may look to provide funding for the Obamacare “cost-sharing reduction” subsidy payments to insurers that President Donald Trump ended in October 2017. And they may look to restore money for Affordable Care Act outreach and enrollment programs after the Trump administration slashed that funding by 84 percent, to $10 million, Pear says. “Another idea is for the federal government to provide money to states to help pay the largest medical claims,” he adds. “Such assistance, which provides insurance for insurance carriers, has proved effective in reducing premiums in Alaska and Minnesota, and several other states will try it next year.”

Investigating the Trump administration ‘sabotage’: “Administration officials who have tried to undo the Affordable Care Act — first by legislation, then by regulation — will find themselves on the defensive, spending far more time answering questions and demands from Congress,” Pear writes.

Reining in prescription drug prices: Trump, Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell have all pointed to this as an area of potential cooperation, But Vox’s Scott calls this “another area where Democrats know they want to act but don’t know yet exactly what they can or should do.” Some options include pushing to let Medicare negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers and requiring makers of brand-name medications to provide samples to manufacturers of generics, potentially speeding the development of less expensive competitors.

“There are a lot of levers to pull to try to reduce drug prices: the patent protections that pharma companies receive for new drugs, the mandated discounts when the government buys drugs for Medicare and Medicaid, existing hurdles to getting generic drugs approved, the tax treatment of drug research and development,” Scott writes. But it’s not clear just what policy mix would really work to bring down drug prices, and the pharmaceutical industry lobby is likely to push back hard on such efforts. Democrats may also be hesitant to give President Trump a high-profile win on the issue ahead of the 2020 election.

Medicare for all: Much of the Democratic Party may be gung-ho for some sort of Medicare-for-all legislation, but don’t expect significant progress over the next two years. “House Democratic leaders probably don’t want to take up such a potentially explosive issue too soon after finally clawing back a modicum of power in Trump’s Washington,” Scott writes. And Democrats have to forge some sort of internal consensus on just what kind of plan they want to push in order to further expand health insurance coverage.

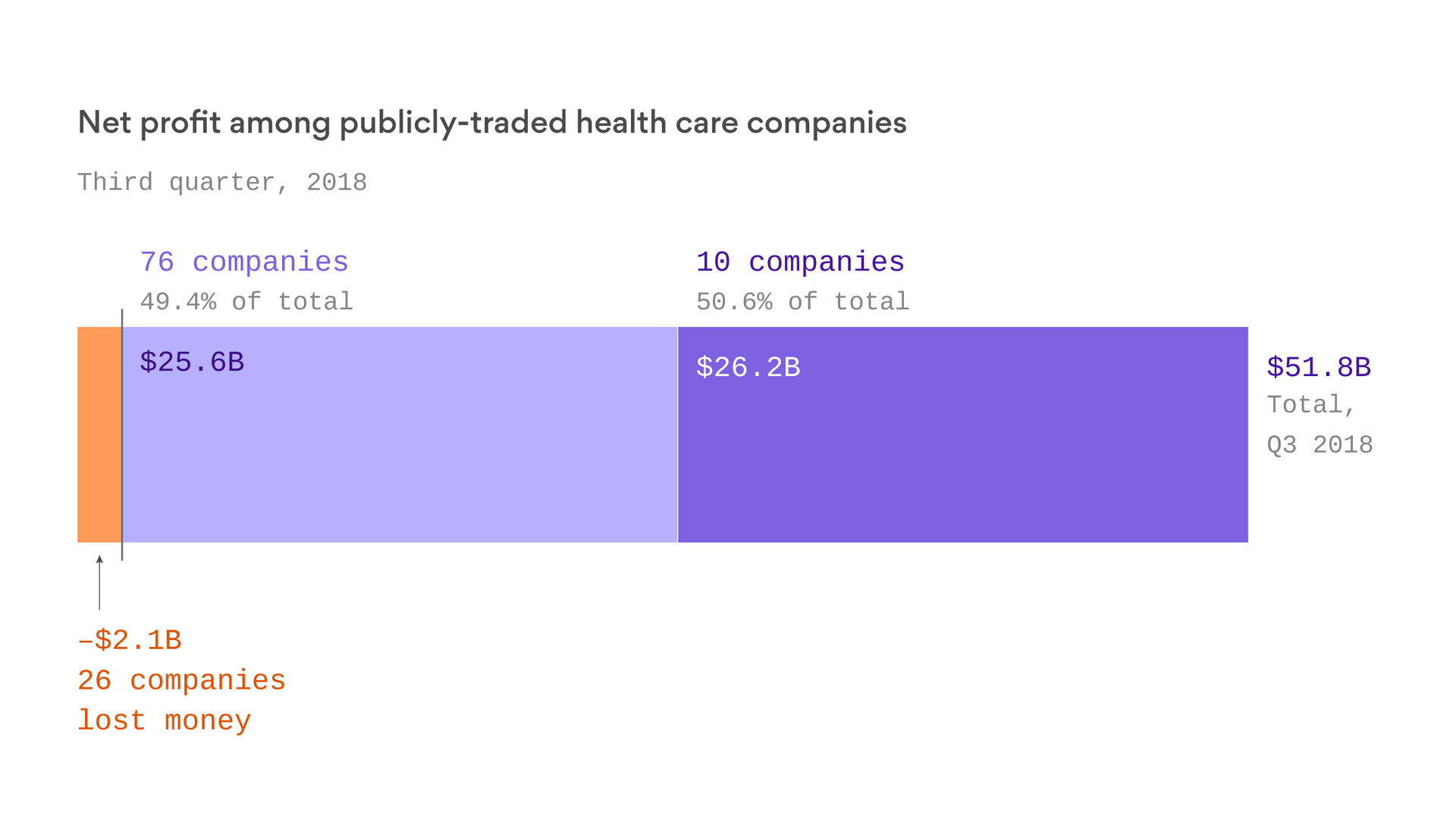

Ten companies controlled half of the health care industry’s $50 billion of global profit in the third quarter of this year, according to an analysis of financial documents for 112 publicly traded health care corporations. Nine of those 10 companies at the top are pharmaceutical firms.

The bottom line: Americans spend a lot more money on hospital and physician care than prescription drugs, but pharmaceutical companies pocket a lot more than other parts of the industry.

Two decades ago, the costs began rising well beyond that of other nations, and in recent years have shot up again. What can explain it?

There was a time when America approximated other wealthy countries in drug spending. But in the late 1990s, U.S. spending took off. It tripled between 1997 and 2007, according to a study in Health Affairs.

Then a slowdown lasted until about 2013, before spending shot up again. What explains these trends?

By 2015, American annual spending on prescription drugs reached about $1,000 per person and 16.7 percent of overall personal health care spending. The Commonwealth Fund compared that level with that of nine other wealthy nations: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Britain.

Among those, Switzerland, second to the United States, was only at $783. Sweden was lowest, at $351. (It should be noted that relative to total health spending, American spending on drugs is consistent with that of other countries, reflecting the fact that we spend a lot more on other care, too.)

Several factors could be at play in America’s spending surge. One is the total amount of prescription drugs used. But Americans do not take a lot more drugs than patients in other countries, as studies document.

In fact, when it comes to drugs primary care doctors typically prescribe — including medications for hypertension, high cholesterol, depression, gastrointestinal conditions and pain — a recent study in the journal Health Policy found that Americans use prescription drugs for 12 percent fewer days per year than their counterparts in other wealthy countries.

Another potential explanation is that Americans take more expensive brand-name drugs than cheaper generics relative to their overseas counterparts. This doesn’t hold up either. We use a greater proportion of generic drugs here than most other countries — 84 percent of prescriptions are generic.

Though Americans take a lower proportion of brand-name drugs, the prices of those drugs are a lot higher than in other countries. For many drugs, U.S. prices are twice those found in Canada, for example.

Prices are a lot higher for brand-name drugs in the United States because we lack the widespread policies to limit drug prices that many other countries have.

“Other countries decline to pay for a drug when the price is too high,” said Rachel Sachs, who studies drug pricing and regulation as an associate professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis. “The United States has been unwilling to do this.”

For example, except in rare cases, Britain will pay for new drugs only when their effectiveness is high relative to their prices. German regulators may decline to reimburse a new drug at rates higher than those paid for older therapies, if they find that it offers no additional benefit. Some other nations base their prices on those charged in Britain, Germany or other countries, Ms. Sachs added.

That, by and large, explains why we spend so much more on drugs in the United States than elsewhere. But what drove the change in the 1990s? One part of the explanation is that a record number of new drugs emerged in that decade.

In particular, sales of costly new hypertension and cancer drugs took off in the 1990s. The number of drugs with sales that topped $1 billion increased to 52 in 2006 from six in 1997. The combination of few price controls and rapid growth of brand-name drugs increased American per capita pharmaceutical spending.

“The scientific explosion of the 1970s and 1980s that allowed us to isolate the genetic basis of certain diseases opened a lot of therapeutic areas for new drugs,” said Aaron Kesselheim, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

He pointed to other factors promoting the growth of drug spending in the 1990s, including increased advertising to physicians and consumers. Regulations on drug ads on TV were relaxed, which led to more advertising. More rapid F.D.A. approvals, fueled by new fees collected from pharmaceutical manufactures that began in 1992, also helped push new drugs to market.

In addition, in the 1990s and through the mid-2000s, coverage for drugs (as well as for other health care) expanded through public programs. Expansions of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program also coincided with increased drug spending. And Medicare adopted a universal prescription drug benefit in 2006. Studies have found that when the potential market for drugs grows, more drugs enter it.

In 2007, U.S. drug spending growth was the slowest since 1974. The slowdown in the mid-2000s can be explained by fewer F.D.A. approvals of blockbuster drugs. Annual F.D.A. approvals of new drugs fell from about 35 in the late 1990s and early 2000s to about 20 per year in 2005-07.

In addition, the patents of many top-selling drugs (like Lipitor) expired, and as American prescription drug use tipped back toward generics, per capita spending leveled off.

The spike starting in 2014 mirrors that of the 1990s. The arrival of expensive specialty drugs for hepatitis C, cystic fibrosis and other conditions fueled spending growth. Many of the new drugs are based on relatively recent advances in science, like the completion of the human genome project.

“Many of the new agents are biologics,” said Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “These drugs have no meaningful competition, and therefore command very high prices.”

A U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issue brief estimated that 30 percent of the rise in drug spending between 2000 and 2014 could be attributed to price increases or greater use of higher-priced drugs. Coverage expansions of the Affordable Care Act also contributed to increased drug spending. In addition, “there has been a lowering of approval standards,” Dr. Bach said. “So more of these new, expensive drugs are making it to market faster.”

“As in the earlier run-up in drug spending, we’re largely uncritical of the price-value trade-off for drugs in the U.S.,” said Michelle Mello, a health law scholar at Stanford. “Though we pay high prices for some drugs of high value, we also pay high prices for drugs of little value. The U.S. stands virtually alone in this.”

If the principal driver of higher American drug spending is higher pricing on new, blockbuster drugs, what does that bode for the future? “I suspect things will get worse before they get better,” Ms. Sachs said. The push for precision medicine — drugs made for smaller populations, including matching to specific genetic characteristics — may make drugs more effective, therefore harder to live without. That’s a recipe for higher prices.

Democratic politicians have tended to be the ones advocating governmental policies to limit drug prices. But recently the Trump administration announced a Medicare drug pricing plan that seems to reflect growing comfort with how drug prices are established overseas, and there’s new optimism the two sides could work together after the results of the midterms. Although the effectiveness of the plan remains unclear, it is clearly a response to public concern about drug prices and spending.

CVS also recently announced it would devise employer drug plans that don’t include drugs with prices out of line with their effectiveness — something more common in other countries but unheard-of in the United States. Even if these efforts don’t take off rapidly, they are early signs that attitudes might be changing.

CS: Hello, and welcome to a special mid-term elections Avalere podcast. This is the last in a three-part series we’re doing on the health policy implications of the mid-term elections, and this time, we actually have results from the mid-term elections! My name is Chris Sloan, I’m a director with the federal and state policy group here at Avalere. Today, we’re going to discuss the results of the mid-term elections and the implications for health policy going forward.

As a reminder for those of you living under rocks, the mid-term elections ended with Democrats taking control of the House while Republicans increased their lead in the Senate. In three states, Medicaid expansion ballot initiative passed, which is likely to lead to about 325,000 new enrollees in Medicaid in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah. Also, Democratic candidates who campaigned on Medicaid expansion won the governors races in Kansas, Maine, and Wisconsin, potentially leading to another 300,000 Medicaid enrollees in those states if they follow through with expansion.

Joining me today to talk about all of this and what we can expect in healthcare from the new Democratically-controlled House is Elizabeth Carpenter. She’s the senior vice president of our federal and state policy group, and she’s the preeminent expert at Avalere in all things health policy. Thanks for being here.

EC: Thanks for having me.

CS: The exit polling for the elections showed that healthcare again was one of the top issues for voters in the elections, eight years after the passage of the ACA. Can you talk about why this issue has continued to be such a big part of campaigns and elections in U.S. politics?

EC: I think this election marked a new high in some ways in terms of how Americans thought and voted on health care. If you had asked me this question leading up to 2016, I would have focused on Americans talking about jobs and the economy, and I would have linked healthcare to jobs and the economy. People often talk about being worried about their job because they are worried about affording their health insurance and their healthcare. This year, from a domestic policy perspective, we saw healthcare at the top of the list, and when you look under the hood, what you see is that people were focused on healthcare costs and not necessarily those costs that are predictable—premiums ranked somewhat low on the list. People were very focused on surprise medical bills and certain areas where we’ve seen increased deductibles and coinsurance that are leading people to be more exposed to system costs. It’s clear that people were focused on healthcare, but they were really focused on having a surprise or unexpected healthcare expense where they were going to have to go out of pocket quite a bit at one time. As the economy has stabilized, people seem to be zeroing on the healthcare front. What I would say is, in all of our policy discussions of healthcare costs, you have to ask yourself, what is the policy doing to address that question? In many cases, I would opine that the policy is not doing much. So it is quite likely that we may see this issue continue as we head towards 2020.

CS: In that vein, a lot of the Democratic candidates this election cycle were campaigning on expansions of public programs, like Medicare for All, Medicare for More. Do we expect that to continue now that Democrats have taken control of the House? How big of an issue do you think recent campaign promises have been?

EC: I would say the Democrats face a choice in this moment about what they want their next step of health reform to look like in advance of 2020. In general, I would very much expect Democrats to use the next year or two to offer thought leadership and position their party in advance of the presidential race. What that looks like, I don’t think we know at this moment. There were a number of candidates, interestingly at the state and federal level, who embraced a Medicare for All or Medicare for More type of approach. Some of those candidates won and some didn’t, and it’s hard to pinpoint what role their position on this circular policy had in those results. But I think it is fair to say that there will be continued debate over what role Medicare and other public programs play in covering our citizens and that Democrats will need to land on something in advance of 2020.

CS: So that was one big issue in the campaign, and another big issue that was on both sides was pre-existing conditions protections that made its way into the campaign season this year. There is still a lawsuit in Texas challenging the Affordable Care Act and the pre-existing conditions now that the individual mandate is gone. Do you see this as an option for some sort of bipartisan consensus coming out of the divided congress? What do you see happening with this issue going forward?

EC: This is another issue where when you look under the hood, even people who say the same things mean potentially very different things. We had candidates on both sides of the isle running ads that talked about their desire to protect pre-existing condition protections, despite the fact that some of those candidates voted to uphold the Affordable Care Act and others voted to repeal it. You asked what might happen if we see the core go down this path where pre-existing conditions projections will be null and void and would Congress sweep in and produce a solution. On face, you could say both parties to some degree do want to maintain protections for some pre-existing conditions. In practice, how you do that gets complicated. Once you open up this particular issue, you’re going to have people on one side of the isle wanting to use it as an opportunity to do certain kinds of reforms, and you have people on the other side of the isle who want to change the insurance market in another way. We’ve heard already from Democrats, for example, who are interested in potentially pursuing limitations on some of the short-term plans, including association health plans and other types of plans that don’t meet all Affordable Care Act requirements. People have already said they want to pursue this in this congress. So you can imagine there being a real need to do something, but at the same time, you can envision how this gets complicated and partisan really quickly. The closer we get to 2020, the more complicated any kind of healthcare debate gets.

CS: Given those realities of a divided government and partisanship, are we in a holding pattern for health policy until 2020 and the next election?

EC: I think a TBD there. Based on what we’ve seen so far, I don’t think anyone holds out a lot of hope for kumbayah and bipartisan progress. At the same time, we’ve seen over the past 24-48 hours various lawmakers on both sides of the isle talking about, for example, the drug pricing issue. The important thing to remember here is that we have a president who is non-traditional in some of his thinking and not necessarily aligned with the positions of the historic Republican party, so to the degree that Congress can reach some kind of alignment, it’s quite possible the President would sign something that another president might not. But it really is up to Congress to decide if they can and want to work together. Both sides at this point are making a calculation about working together and governing is good for them heading into the next election or if fostering gridlock and highlighting differences is a better political path.

CS: Great. Well, thank you so much for being with us. That wraps up our final episode of our three-part Avalere mid-term elections podcast series. As always, watch for more updates and analysis from Avalere over the coming weeks. Feel free to reach out to us with any questions. You are listening to Avalere Podcasts.

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/9-hospitals-with-strong-finances-110818.html

Here are nine hospitals and health systems with strong operational metrics and solid financial positions, according to recent reports from Moody’s Investors Service, Fitch Ratings and S&P Global Ratings.

1. Wausau, Wis.-based Aspirus has an “AA-” rating and stable outlook with S&P. The health system has solid debt and liquidity metrics, according to S&P.

2. Charlotte, N.C.-based Atrium Health has an “AA-” rating and stable outlook with S&P. The health system has a strong operating profile, favorable payer mix, healthy financial performance and sustained volume growth, according to S&P.

3. St. Louis-based Mercy Health has an “Aa3” rating and stable outlook with Moody’s. The health system has favorable cash flow metrics, a solid strategic growth plan, a broad service area and improving operating margins, according to Moody’s.

4. Traverse City, Mich.-based Munson Healthcare has an “AA-” rating and positive outlook with Fitch. The health system has a leading market share in a favorable demographic area and a healthy net leverage position, according to Fitch.

5. Parkview Regional Medical Center in Fort Wayne, Ind., has an “AA-” rating and stable outlook with S&P. The hospital is executing on its strategic plan, and S&P expects it to maintain its balance sheet metrics.

6. Vancouver, Wash.-based PeaceHealth has an “AA-” rating and stable outlook with Fitch. The health system has a leading market position, robust reserves and strong cash flow, according to Fitch.

7. Baltimore-based Johns Hopkins Health System has an “Aa2” rating and stable outlook with Moody’s. The health system has favorable liquidity metrics, strong fundraising capabilities, a healthy market position and regional brand recognition, according to Moody’s.

8. Madison-based University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics has an “Aa3” rating and stable outlook with Moody’s. The hospital has an integral relationship with the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is a major academic medical center and quaternary referral center for the region and state, according to Moody’s.

9. Willis-Knighton Medical Center in Shreveport, La., has an “AA-” rating and positive outlook with Fitch. The hospital has a leading inpatient market share, favorable payer mix and healthy operating margins, according to Fitch.

A Kansas physician and Hutchinson (Kan.) Clinic are defendants in a False Claims Act case the federal government recently intervened in, according to the Great Bend Tribune.

The government alleges Mark Fesen, MD, and Hutchinson Clinic billed Medicare and Tricare for more than $30 million for medically unnecessary medications and treatments, including chemotherapy.

The 45-page federal complaint provides nine examples of patients who received unnecessary treatments.

“These patient examples are not isolated examples, but instead representative examples of the medically unnecessary services Fesen and Hutchinson Clinic repeatedly billed to Medicare and Tricare,” states the complaint. “This is supported by the clinic’s own internal audits that found widespread problems with Fesen’s chemotherapy regimens, and particularly his use of Rituxan.”

A clinical pharmacist who worked in Hutchinson Clinic’s oncology department from 2007-14 originally brought the allegations against Dr. Fesen and the clinic under the qui tam, or whistle-blower, provisions of the False Claims Act.

A federal judge has temporarily shut down Miami-based Simple Health Plans at the request of the Federal Trade Commission.

In a federal complaint against Simple Health Plans, the company’s owner and five other entities, the FTC alleges Simple Health Plans collected more than $100 million by selling worthless health plans to thousands of people. The company allegedly misled consumers to think they were buying comprehensive “PPO” health insurance plans when they were actually purchasing plans that provided no coverage for pre-existing conditions or prescription medications.

Many of the people who purchased plans from Simple Health Plans are facing hefty medical bills for expenses they assumed would be covered by their health insurance plan. In addition, because the limited health plans do not qualify as health insurance under the ACA, some people were subject to a fee imposed on those who can afford to buy health insurance but choose not to.

The FTC is seeking to permanently shut down Simple Health Plans and to have the company return money to consumers.

The long-time president and CEO of Our Lady of the Lake Foundation, the fundraising arm that supports Baton Rouge, La.-based Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center, was fired after a third-party investigation revealed “a pattern of forgery and embezzlement of funds,” according to The Advocate.

John Paul Funes, who led several multimillion-dollar fundraising campaigns for the hospital, headed the foundation for more than 10 years.

“We are shocked and appalled at what we have learned,” Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center said in a statement. “Our Lady of the Lake Foundation is integral to our healing ministry and helped us reach so many important goals that would have been unattainable otherwise.”

The hospital declined to release additional details pending the criminal investigation, according to the report.

“Mr. Funes’ actions in no way represent the values and mission of the Our Lady of the Lake and the Foundation, and the hundreds of volunteers and donors who have given so much over the years,” the hospital’s statement reads.

https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/mid-term-message-dont-mess-my-healthcare

You can’t undo an entitlement.

‘Repeal and replace’ is dead. Drug pricing reforms a likely area of bipartisan consensus.

Democrats can push Medicare For All at their own peril.

For healthcare economist Gail Wilensky, the big message that voters sent to their elected officials during Tuesday’s mid-term elections was straightforward and simple.

“Don’t mess with my healthcare,” says Wilensky, a senior fellow at Project HOPE and a former MedPAC chair.

“It’s as clear as that. There were no subtleties involved here,” she says. “That includes protections for pre-existing conditions and added coverage under Medicaid.”

Consider what happened on Tuesday:

Wilensky says the mid-terms results reinforce one of the oldest truisms in politics: Once an entitlement is proffered, there’s no going back.

“There is no precedent that I’m aware of in American political history where a benefit can be taken away,” she says. “Once granted, it can be modified, it can be increased, it can be augmented in some way, but there’s no taking it away after it’s been in place.”

When Democrats took control of the House, Wilensky says, they drove a stake through the heart of the “repeal and replace” movement.

“Republicans couldn’t even get that done when they control both houses of Congress, she says. “It’s a non-issue, in part because a lot of Republicans support major provisions of the Affordable Care Act.”

With repealing the ACA off the table, Democrats and Republicans might find common ground on issues such as drug pricing.

“That’s clearly is the most obvious, in general, but the specifics of what you want to do become much more challenging,” Wilensky says. “Typically, Democrats want to use administered pricing the way that we use administer pricing in parts of Medicare. I don’t know how much Republican support there is for that.”

The two parties could reach some sort of bipartisan agreement on Medicare Part B drugs, Wilensky says, because it’s a smaller program and the drugs are generally much more expensive.

“Most members of Congress are not talking about messing around with Part D, the ambulatory prescription drug coverage,” Wilensky says. “So it really has to do either with the expensive infusion drugs that are administered in the physician’s office or maybe something about drug advertising. Even then, it’s going to be hard lift when you actually get down to the specifics.”

Besides, Wilensky says, it’s not the cost of drugs that’s at the heart of voter agitation.

“You have to unpack what they’re saying to figure out what they’re actually pushing for,” she says. “People couldn’t care less about drug prices. They only care about what it costs them. So when they talk about drug prices they mean, ‘I want to spend less for the drugs I want, and I don’t want any constraints about what I can order.’

More likely, she says, common ground could be found in arcane areas such as mandating greater transparency for pharmacy benefits managers, and changing PBMs’ rebate structure.

Wilensky warns that giddy Democrats should learn from the mistakes of Republicans in the mid-terms and not attempt to force a Medicare-For-All solution on a wary public.

“First of all, they’re going to have to define what it means,” she says. “But, you have to be very careful because historically there’s not been warm and fuzzy response to taking away people’s employer-sponsored insurance.”

“Again, historically, when candidates mess around with employer-sponsored insurance they have gotten themselves into trouble,” she says. “Most people would like to keep what they have, because keeping what you have is much safer than going with something as yet to be defined.”