Cartoon – Promoted to Plant Manager

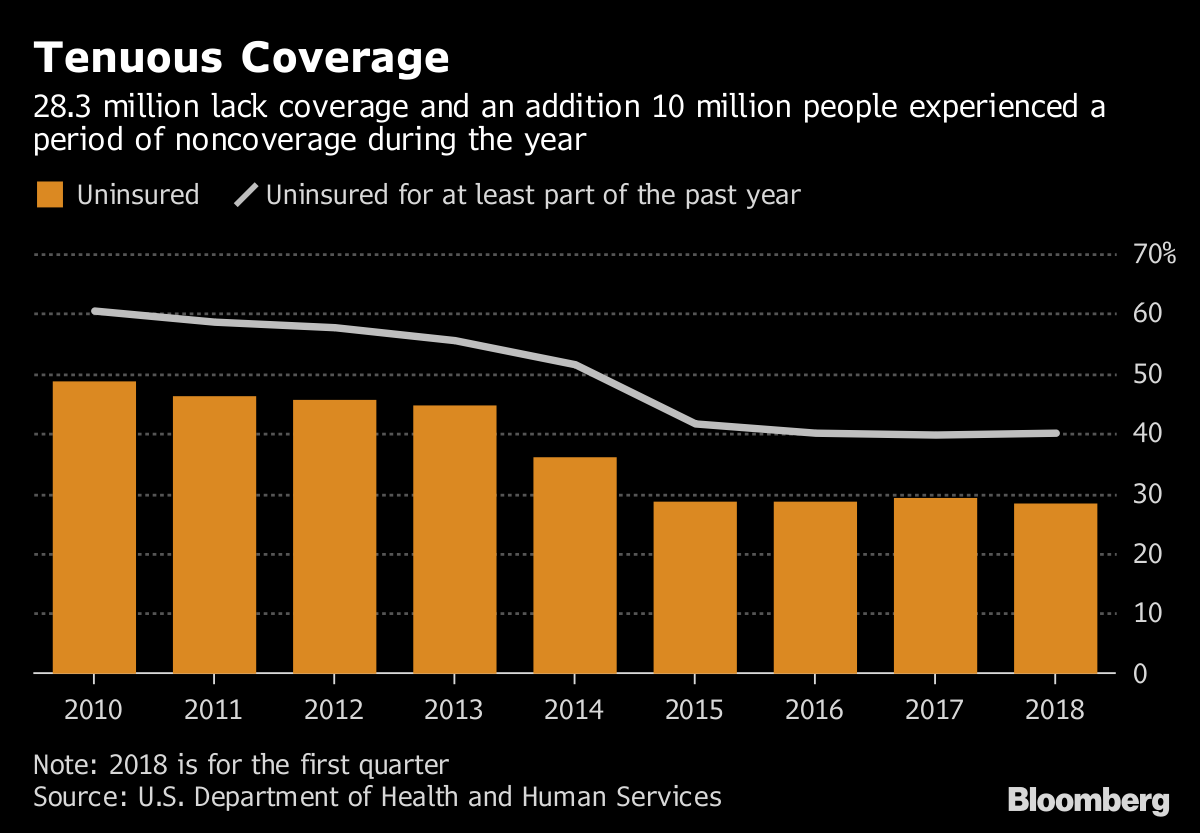

Fewer Americans lack health insurance — but the gap remains wide, especially in some pro-Trump states.

The number of uninsured declined to 28.3 million in the first quarter, down from 29.3 last year — and 48.6 million in 2010, the year the Affordable Care Act was signed into law by then-President Barack Obama, according to data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The distribution, however, is uneven with data for south central states — Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas — showing almost a quarter of adults lacking health care coverage. President Donald Trump, who has opposed Obamacare, won those four states in the 2016 presidential election.

The CDC data also show:

http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180831/NEWS/180839976

For months, congressional Republicans have ignored the Texas-led lawsuit seeking to overturn the Affordable Care Act. With the midterm elections looming, talk of the case threatened to reopen wounds from failed attempts to repeal the law. Not to mention that legal experts have been panning the basis of the suit.

But that’s all changing as the ACA faces its day in court … again. The queasy feeling of uncertainty that surrounded the law just one year ago is back. The level of panic setting in for the industry and lawmakers is pinned to oral arguments set for Sept. 5 in Texas vs. Azar. Twenty Republican state attorneys general, led by Ken Paxton of Texas, are seeking a preliminary injunction to halt enforcement of the law effective Jan. 1. Their argument is built around the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling in which Chief Justice John Roberts said the law is constitutional because it falls under Congress’ taxing authority. The AGs have seized on the congressional GOP’s effective elimination of the individual mandate penalty in the 2017 tax overhaul as grounds to invalidate the law.

They have the Trump administration on their side, in part. The Justice Department in June filed a brief arguing that the individual mandate as well as such consumer protection provisions as barring insurance companies from denying coverage to people with pre-existing conditions are unconstitutional. But the department stopped short of suggesting that the entire law be vacated.

Conservative U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor will hear the case in Austin, Texas. O’Connor has already ruled against an ACA provision that prohibited physicians from refusing to perform abortions or gender-assignment surgery based on religious beliefs, and he is considered a wild card.

Even ACA supporters who downplay the legal standing of the case are bracing for the possibility that O’Connor will side with the plaintiffs, who ultimately see a path to the Supreme Court.

Republicans, meanwhile, are trying to head off a potential political storm. A coalition of Senate Republicans led by Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina introduced a bill to codify guaranteed issue for people with pre-existing conditions into HIPAA laws. But they left out the key mandate that insurers can’t exclude coverage of treatment for pre-existing conditions. That omission left health insurers scratching their heads and Democrats came out swinging, with Democratic Sen. Claire McCaskill of Missouri dubbing the measure “a cruel hoax.”

The politics around coverage protections will really start to matter for Republicans should O’Connor signal support for the plaintiff states, according to Rodney Whitlock, a Washington healthcare strategist and former GOP Senate staffer. “It ups the pressure considerably,” he said. “There’s no question it complicates things for Republicans if a decision comes down in October.”

Insurers are on the lookout for signs of what could happen next. If O’Connor’s decision comes down before open enrollment starts on Nov. 1, the GOP will feel increasing pressure to do something substantive, according to an industry official who asked not to be identified.

Although a ruling striking down the law wouldn’t necessarily impact the individual market in 2019, it would spark the kind of massive uncertainty that insurers hate and complained of last year during the GOP repeal-and-replace efforts.

America’s Health Insurance Plans filed an amicus brief urging the court to deny the request for a preliminary injunction, citing the massive impact such a move would have on insurers in the individual market, Medicaid managed care and Medicare Advantage plans.

“It creates a lot of impetus for federal or state action,” the insurance official said, noting that insurers would have to rely on HHS to interpret how the law’s regulations would apply going forward. If mounting court decisions start to drastically affect the law’s mandates, it would fall to HHS how to manage complicated questions around how to follow ACA rules.

HHS and Justice Department officials declined to comment. CMS Administrator Seema Verma in August told McCaskill when pressed at a Senate committee hearing that she would support legislation to protect pre-existing conditions, but she declined to specify how the CMS would respond administratively if the suit succeeds.

For now, lawmakers aren’t showing any willingness to take a bipartisan approach. The House GOP plans to introduce a companion bill to the Senate measure, Tillis told Modern Healthcare last week. Meanwhile Democrats have made hay over the fact that the protections in his legislation are incomplete. Tillis said leaving out the prohibition of coverage exclusions was not intentional and GOP senators would look again at the bill if the lawsuit advances.

He added that he envisions the legislation as just one piece that could build into a bigger overhaul effort, and wants to see protections of other popular provisions such as allowing people up to age 26 to stay on their parents’ health insurance.

“It’s similar to what we talked about last year,” Tillis said, referencing the 2017 repeal-and-replace efforts. “Any sort of court challenge that would cause a precipitous voiding of Obamacare would leave a lot of people in the lurch, and one of those areas is pre-existing conditions.”

Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.), who spearheaded the last major GOP effort to repeal and replace the ACA last year, also said he would want to look at more comprehensive legislation if the lawsuit advances. “I certainly would,” Cassidy said. “I can’t speak for all, but I do think there would be a drive to.”

How Republicans will move past messaging and into action remains to be seen, Whitlock said.

“If you think of the seminal moments of 2017, you think of pre-existing conditions and the Jimmy Kimmel test,” Whitlock said, referencing the talk show host’s attack on the repeal-and-replace effort following emergency heart surgery for his newborn son. “This was a big deal because people were concerned. It is a very important issue, and it’s also one that Republicans have tried to say in every bill that they’re trying to protect. They have been successful to varying degrees in making that case. But with the Texas lawsuit, there’s no protecting it. It says, throw out the entire ACA root and branch.”

And as nomination hearings for Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh get underway Sept. 4, Democrats will keep using the GOP’s dilemma as a cudgel. McCaskill, for instance, is leveraging the issue in her neck-and-neck race against Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley, who is part of the lawsuit.

“How do you have a pre-existing conditions bill that says we’re not going to protect someone with a pre-existing condition?” she told reporters last week. “It’s embarrassing, it’s the Potomac two-step. Do they think nobody’s paying attention? They’re just trying to cover themselves politically, isn’t it obvious?”

And then there’s the other political dilemma for Republicans who want to show they can secure Obamacare’s protections: convincing their base that they still fundamentally oppose Obamacare even if they don’t want to talk about repeal-and-replace anymore.

“You can be sure there are folks out there who really desperately don’t want to see the Texas side laughed out of court,” Whitlock said. “It destroys the whole narrative about the lawsuit. It’s this bizarre dynamic where an obscure lawsuit that has no legal basis whatsoever leaves the opportunity to talk about” repeal.

He added: “There are people who are flat-earthers on ACA, still preaching complete and total repeal.”

The fate of Medicaid expansion, a central tenet of President Obama’s signature health-care legislation, is in the hands of the people in several states.

In Idaho, Nebraska and Utah, voters will decide whether to make more low-income people, those up to 138 percent of the federal poverty line, eligible for Medicaid, the government-run health insurance program. In most of the other states, who voters elect as governor and to the legislature will influence the direction of this health-care policy for years to come.

Since the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, 33 states have expanded Medicaid, largely along partisan lines, with Republicans leading the holdout movement. But in some cases, Republican governors tried for years to convince their GOP legislatures to expand.

Health policy experts say that, generally, a state’s status of expansion guides which races are most important to watch in the midterms.

“For a state that hasn’t yet expanded, the governor can’t do it all, so you have to watch what happens with the legislature,” says David Jones, associate professor of health law at Boston University who recently examined where Medicaid expansion appears more vulnerable. “But for states that have already expanded, the legislature doesn’t matter as much” because the governor has authority to tweak the current law or to end expansion in some cases.

The midterms come at a crucial time for health care. The Trump administration gave states the greenlight to adopt new rules for Medicaid that the Obama administration rejected. For instance, Arkansas, Kentucky, Indiana and New Hampshire have been approved to add work requirements, and several other states have applied. In July, a federal judge struck down Kentucky’s work requirements plan, putting the rest of the states’ policies into legal jeopardy. Despite the ruling, the Trump administration has signaled that it plans to proceed with work requirements.

Michigan is one expansion state where health policy could veer far to the right if the Republican nominee for governor, Bill Schuette, wins what is considered a tossup race. Schuette, the state’s attorney general, leans more conservative than term-limited Republican Gov. Rick Snyder. On the campaign trail, Schuette has supported repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act.

“He talks a lot about what he doesn’t like [about the ACA], but he has yet to say what he’d do that’s positive,” says Marianne Udow-Phillips, executive director of the Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation based in Ann Arbor, Mich. “I see him being in the mold of Scott Pruitt at the Environmental Protection Agency, doing a lot of rolling back of regulations.”

In Michigan, 680,000 people gained coverage under Medicaid expansion, and 350,000 could lose it if work requirements are put in place. Snyder signed a bill in June to submit a waiver to the federal government that, if approved, would require Medicaid recipients in the state to have a job.

“We’ve gotten used to thinking that Michigan is a moderate state because they have Democratic senators and sometimes go blue in presidential elections,” says Jones, “but … it’s a pretty conservative group of senators in the statehouse,” and a more conservative governor might be able to drum up support for far-right Medicaid changes.

Schuette’s Democratic opponent, Gretchen Whitmer, supports Medicaid expansion and opposes the work requirements waiver, according to a spokesperson in her campaign office.

In Ohio, another expansion state, GOP Gov. John Kasich is term-limited. While he is one of the staunchest defenders of Medicaid expansion, he did pass off a waiver request for work requirements to the feds. Republican Attorney General Mike DeWine and Democrat Richard Cordray, the former head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, are in a tossup race to succeed him.

DeWine leans more pragmatic in general, so John Corlette, executive director of the Center for Community Solutions based in Cleveland, says “I would expect his approach would be closer to Kasich.” DeWine has said he supports expansion with a work component, while Cordray supports expansion with no work requirements.

In Ohio, work requirements threaten coverage for 36,000 adults.

If any states elect governors who are more conservative than their predecessors, “Kentucky is a good example of what a change in leadership can mean for Medicaid expansion,” says Jones. There, a Democratic governor expanded Medicaid to 500,000 Kentuckians. When Republican Matt Bevin was elected in 2015, he added work requirements, along with premiums and reporting income changes.

A governor’s authority, however, isn’t limitless. Since residents in Maine voted in favor of expansion last year, GOP Gov. Paul LePage has refused to enact the policy. The state’s Supreme Court last week ordered him to move forward with expansion.

Implementation of it, though, will likely fall to his successor. LePage is term-limited. Running to take his place is Democratic Attorney General Janet Mills, who supports expansion. Republican challenger Shawn Moody, a business owner, is following LePage’s lead and opposing it. If the state expands Medicaid per the court’s orders, 70,000 people would gain coverage.

Among states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, Jones says the state to watch is Kansas. In 2017, the legislature passed a Medicaid expansion bill, but then-GOP Gov. Sam Brownback vetoed it. The legislature narrowly missed getting enough votes to override him.

While it’s unlikely that the legislature in a state that deep red would flip Democrat, “the state seems to be treading more moderate,” says Jones. On a recent trip to Topeka, he says “many Republicans were willing to say they would support Medicaid expansion. They saw it as a way to save their rural hospitals.”

The governor’s race in the state is a matchup between hardline conservative Secretary of State Kris Kobach and Democratic state Sen. Laura Kelly. Kobach has a slight edge. Kelly has vowed to expand Medicaid, and Kobach is opposed to it.

While it’s a wild card, the political landscape in Florida has the potiential to completely shift in November, laying the groundwork for the state to expand Medicaid. Despite support from GOP Gov. Rick Scott, who is running for U.S. Senate, the GOP-controlled legislature has rebuffed all expansion efforts over the years.

Now, Democrats have a real shot at taking control in the Senate. While it’s unlikely they’ll take control of the House, they are expected to gain ground. The governor’s race is between Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, who supports the Democratic Socialist platform of “Medicare for all.” His opponent, Republican Congressman Ron DeSantis, is against expanding Medicaid.

“Supporters of the ACA think of Florida as the holy grail in terms of expansion,” says Jones.

Confirmation hearings for U.S. Supreme Court nominee Judge Brett Kavanaugh began with fireworks Tuesday morning before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Democrats and protestors alike interrupted Chairman Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, repeatedly in apparent attempts to block the hearing from proceeding. The episode reflects a high-stakes and largely partisan debate that could dramatically impact U.S. healthcare for decades to come.

Kavanaugh, 53, would be the second-youngest member on the court if confirmed, resulting in a 5–4 reliably conservative majority, as NPR reported. His approach to hot-button healthcare topics, such as abortion and the Affordable Care Act, have received particular scrutiny.

On the presidential campaign trail, then-candidate Donald Trump promised to nominate only justices who would overturn Roe v. Wade. Kavanaugh reportedly told one senator that he views Roe as “settled law.” But that doesn’t necessarily mean he believes Roe can’t be overturned, as The Atlantic’s Garrett Epps wrote.

Kanaugh dissented in an opinion last year, writing that the government has “permissible interests in favoring fetal life, protecting the best interests of a minor, and refraining from facilitating an abortion,” and it “may further those interests so long as it does not impose an undue burden on a woman seeking an abortion.”

Another healthcare-related decision by Kavanaugh likely to come up is his 2011 dissent holding that the ACA’s individual mandate was legal as a tax authorized by the Commerce Clause.

Kavanaugh’s reading could come full circle, if a legal challenge launched by conservative states progresses to the Supreme Court. The states argue that the entire ACA was rendered unconstitutional when Congress zeroed out the tax penalty tied to the individual mandate, canceling its status as a tax. In response to the lawsuit, the Trump administration abandoned its defense of key ACA provisions.

It’s worth noting, though, as Bloomberg’s Sahil Kapur did, that Kavanaugh’s 2011 ACA ruling effectively “ducked the issue,” enabling him to avoid ruling on the ACA’s merits. That’s significant because some senators have said Kavanaugh’s views on the ACA will affect how they vote on his nomination.

While liberals fear that Kavanaugh could contribute to the ACA’s dismantling, some conservatives worry he’s too moderate on the ACA. Kavanaugh himself has reportedly signaled in private meetings with Democrats that that he’s skeptical of certain claims in the current Republican-led effort to overturn the Obama-era law.