https://www.axios.com/2026/01/05/economy-tariffs-ai

Tariff drama and tax cuts! AI spending and AI-spurred job losses! New Federal Reserve leadership! It is on track to be a big year across all the key policy areas of interest to economy-watchers.

The big picture:

Seismic changes have been set in motion by the Trump administration’s sweeping policy agenda and a mega-wave of investment in artificial intelligence — likely to determine the fate of the economy in 2026.

1. The AI economy

The biggest macro questions are whether the alarm bells about AI and the labor market will start to ring true — and whether the productivity effects move from just anecdotes to the economic data.

- Last year, much evidence pointed to AI as a marginal part of the labor market slowdown. Some economists (and officials inside the White House) argue that broader adoption of the technology would boost the labor market, at least in the short term.

Of note:

AI spending buoyed economic growth, at least in the first nine months of 2025. It is also lifting the stock market, which might help support spending among wealthier consumers.

- Whether this turns out to be a bubble that pops — and the extent such a risk poses to the broader financial system as the Fed rolls back regulations — is the related theme to watch.

- That said, any correction in AI investment looks more likely to be a down-the-road story than a 2026 issue.

2. Tax cut boost

The One Big, Beautiful Bill Act, signed into law in July, is set to have its maximum economic punch in the early months of 2026, a likely tailwind for overall economic growth.

- But how large, how broad-based and how sustained that boost will turn out to be remains to be seen.

Zoom in:

Fiscal policy is on track to add about 2.3 percentage points to first-quarter GDP growth, per data from the Hutchins Center Fiscal Impact Measure from the Brookings Institution.

- On the individual tax side, beneficiaries of policies like a deduction for tip income, Social Security payments and expanded deductibility of state and local tax are on track to generate super-sized tax refunds this spring,

- On the corporate side, businesses are enjoying new tax incentives for capital spending, especially on factories.

- Federal spending on immigration enforcement, meanwhile, is ramping up due to the legislation.

3. Trade uncertainty (maybe) resolving

Any day now, the Supreme Court will hand down a decision that might scramble the centerpiece of President Trump’s economic agenda: the ability to impose huge tariffs unilaterally.

- If the court strikes down the bulk of Trump’s tariffs, fiscal revenues could be put at risk, resulting in a chaotic refund process.

- That said, the ruling will help create some guardrails on what kinds of legal authority the president has to impose unilateral tariffs. That, in turn, could lead to a more stable tariff picture (albeit with much higher rates than pre-2025).

- While there are other authorities the president can use to enact tariffs besides the sweeping authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act he has claimed, they require a more deliberative process than the kind of whipsawing that importers faced last year.

4. Future of the Fed

Fed chair Jerome Powell’s term is up in May, and Trump’s selection of his successor is imminent, with Kevin Hassett and Kevin Warsh the leading job candidates.

Zoom out:

Whoever takes the reins will face immense pressure from Trump to lower interest rates to rock-bottom levels — amid continued high inflation — and how they handle that pressure may determine the future of the central bank’s independence from the White House.

- Trump expects the future Fed chair to consult with him on rates, while casting the intention to lower rates as a key qualification for the next leader.

- The question is whether the next Fed chair can resist that political pressure and whether financial markets believe that is the case. If bond markets lose confidence that the Fed will raise short-term rates if necessary to combat an inflation surge, it could paradoxically drive up long-term rates.

- Another huge question: the makeup of the influential Fed board, with the Supreme Court also set to decide whether Trump can fire governor Lisa Cook and, by extension, other Biden-appointed governors.

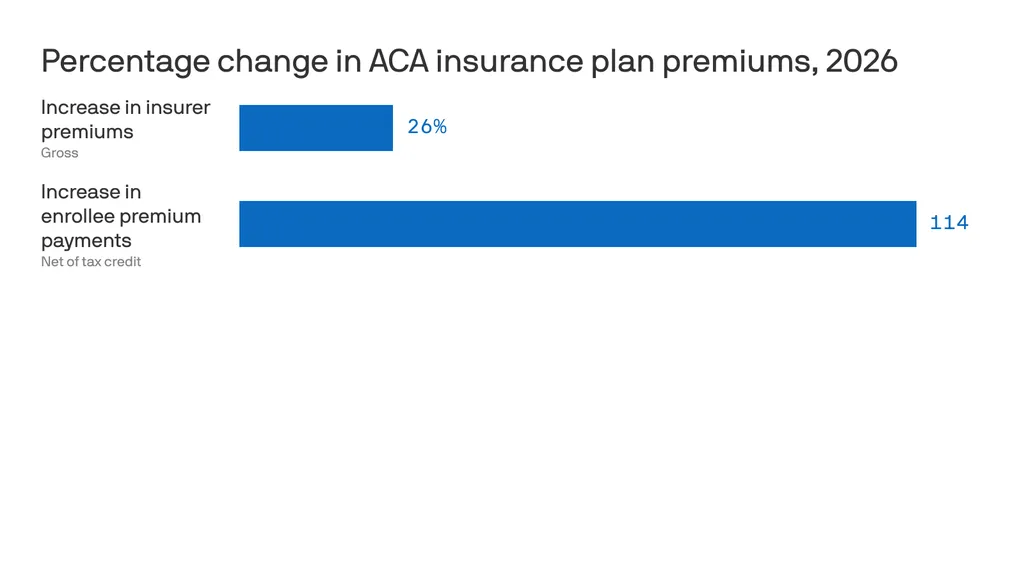

5. Affordability and the midterms

With voters going to the polls in November, the cost of living is emerging as a core battleground.

- Democrats seeking to take control of Congress are making political hay about the affordability crisis.

- Trump has called the term affordability a “con job,” but said recently that he believes “pricing” will be a major election issue.

Flashback:

The Consumer Price Index is up a moderate 2.7% over the last 12 months, but that increase came on top of the Biden-era inflation surge.

- The index is up 23.7% since January 2021, even more for some often-purchased subcategories, including groceries (up 24.6%).

Over the holiday break, the administration quietly shelved plans to impose levies on imported pasta and furniture.

- It’s a hint that the White House is eager to avoid trade levies that might flow directly to prices consumers pay, as opposed to affecting input costs for businesses.