Frustrated with insurers, some large companies — including a certain cable behemoth — are shedding long-held practices and adopting a do-it-yourself approach.

It’s hard to think of a company that seems less likely to transform health care.

It isn’t headquartered in Silicon Valley, with all the venture-backed start-ups. It’s not among the corporate giants — Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase — that recently announced, with much fanfare, a plan to overhaul the medical-industrial complex for their employees.

And it is among the most hated companies in the United States, according to many surveys on customer satisfaction.

It’s Comcast. The nation’s largest cable company — the $169 billion Philadelphia-based behemoth that also controls Universal Parks & Resorts, “Sunday Night Football” and MSNBC — is among a handful of employers declaring progress in reaching a much-desired goal. In the last five years, the company says, its health care costs have stayed nearly flat. They are increasing by about 1 percent a year, well under the 3 percent average of other large employers and below general inflation.

“They’re the most interesting and creative employer when it comes to health care benefits,” said Dr. Bob Kocher, a partner at Venrock, a venture capital firm whose portfolio companies have done business with Comcast. (The cable company declined over several months to provide executives for an interview on this topic.)

Comcast, which spends roughly $1.3 billion a year on health care for its 225,000 employees and families, has steered away from some of the traditional methods other companies impose to contain medical expenses. It rejected the popular corporate tack of getting employees to shoulder more of the rising costs — high-deductible plans, a mechanism that is notorious for discouraging people from seeking medical help.

Most employers now require their workers to pay a deductible before their insurance kicks in, with individuals on the hook for $1,500, on average, in upfront payouts, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Instead, Comcast lowered its deductible to $250 for most of its workers.

“We believe that no one should be required to be an expert in health care,” Shawn Leavitt, the executive overseeing benefits at Comcast, said in a 2015 interview with a consultant. “Our model is based on providing employees support and assistance in making the right decisions for themselves and their families. Employees should not feel alone, confused and overwhelmed when it comes to understanding and selecting their benefits.”

Cable TV subscribers who have felt confused and overwhelmed when dealing with Comcast customer service may be surprised to learn how nimbly the company has upgraded services for its employees. While Comcast continues to work with insurers, it has largely shunned them as a source of innovation. Instead, it has assembled its own portfolio of companies that it contracts with, and invests in some of them through a venture capital arm, Comcast Ventures.

Turning to health start-ups for new benefits

One such company is Accolade, in which Comcast is an investor, and which provides independent guides called navigators to help employees use their health benefits. Another, called Grand Rounds, offers second opinions and help in finding a doctor. Comcast was also among the first major employers to offer workers access to a doctor via cellphone through Doctor on Demand, a telehealth company.

“We see the start-up community as where the real disruption is taking place,” said Brian Marcotte, the chief executive of the National Business Group on Health, which represents large employers. “We weren’t seeing enough innovation.” The group now vets some of these companies for employers, including Comcast.

Comcast “is the tip of the spear,” Mr. Marcotte said.

The corporation, of course, is controlling costs and offering these unusual benefits out of self-interest. And these services are sometimes handed out at the expense of improving wages. In a tight labor market, Comcast also needs to remain competitive for not only highly skilled employees, but also lower-wage workers whose direct contact with customers has generated so much dissatisfaction over the years. “We do these things because it’s great for business,” Mr. Leavitt said.

But much of what sets Comcast apart is its willingness to directly tackle its medical costs rather than relying on others — insurers, consultants or associations. It’s a luxury only the largest companies can afford, and roughly a fifth of big companies continue to see annual cost increases of more than 10 percent, according to Mercer, a benefits consultant.

While fate may play a role — a single expensive medical claim can drive up a company’s costs in any given year — employers, like Comcast, that use a variety of strategies tend to have the lowest annual increases. “You attack this thing from different angles,” said Beth Umland, Mercer’s director of research for health and benefits. “The intensity of effort pays off.”

Some companies are shaking up hospitals and doctors

Other employers are focusing more attention on unsatisfying hospitals and doctors. Walmart has been at the forefront of efforts to direct employees to specific providers to get medical care, even if it means paying their travel to places like the Mayo Clinic.

The retailer said it had found, for example, that employees were being told they needed back surgery even when they would not benefit from the procedure. “Walmart isn’t going to stand for this,” said Marcus Osborne, a benefits executive, at a health business conference. “We aren’t going to sit around to try to build another coalition or bureaucracy.”

The majority of working-age Americans — some 155 million — get their health insurance through an employer, and most companies cover their own medical costs. The companies rely on insurers to handle the paperwork and to contract with hospitals and doctors. Insurers may also suggest programs like disease management or wellness to help companies control costs.

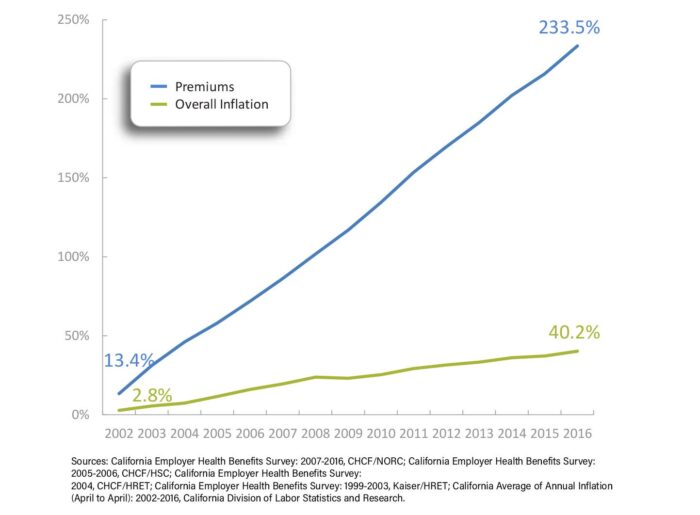

But employers, including that Amazon-Berkshire-JPMorgan alliance, are increasingly unhappy with the nation’s health care systems. Companies are paying more than they ever have. And their employees, saddled with escalating out-of-pocket costs and a confusing maze, aren’t well served, either. “The results haven’t been there,” said Jim Winkler, a senior executive at Aon, a benefits consultant. “There’s frustration.”

At Comcast, some workers probably miss out on the new ventures altogether and others don’t have much choice but to go along. The company’s relationship with labor is often strained, and it has largely managed to fend off efforts by groups like the Communications Workers of America to organize its employees. Robert Speer, an official with a local of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers in New Jersey that represents about 180 workers, noted the company’s use of independent contractors to do much of its work, none of whom are eligible for benefits and can be paid by the job rather than hourly. “You are making no money,” he said.

And, like many other workers, many employees are being pinched by the rising cost of premiums, Mr. Speer said.

Comcast workers with company coverage are told to go to Accolade first. Its phone number appears on the back of their insurance cards and on the benefits website. “The key to Accolade’s success is being the one place to go,” said Tom Spann, a co-founder of the company.

Geoff Girardin, 27, used Accolade when he worked at Comcast a few years ago and he and his wife were expecting. “Our introduction to Accolade was our introduction to our first kid,” Mr. Girardin said. He credits Accolade for telling him his wife was eligible for a free breast pump and helping find a pediatrician when the family moved. “It was a huge, huge help to have somebody who knew the ins and outs” of the system, he said.

For employees like Jerry Kosturko, 63, who survived colon cancer, Accolade was helpful in steering him through complicated medical decisions. When he needed an M.R.I., his navigator recommended a free-standing imaging center to save money. “They will tell me what things will cost ahead of time,” Mr. Kosturko said.

A nurse at Accolade helped him manage symptoms after he had surgery for bladder cancer in 2014. He developed terrible spasms because, he said, he wasn’t warned to avoid caffeine. The Accolade nurse thought to ask him and quickly urged him to call his doctor for medicine to ease his symptoms.

Mr. Kosturko also turned to Grand Rounds when his doctor thought he might need to stay overnight in the hospital to be tested for sleep apnea. The second opinion convinced him he did not.

In complicated cases, Grand Rounds can serve as a check on the network assembled by the insurer. It pointed to the case of Ana Reyes, 39, who does not work for Comcast and had contacted Grand Rounds after treatment for cervical cancer. When she continued to have symptoms, she says, she was told to wait to see if they persisted.

“This is my life at stake,” she recalled in an interview. “I need to know what I’m doing is the best plan.” Grand Rounds asked a specialist at Duke University School of Medicine, Dr. Andrew Berchuck, to review her case.

“Grand Rounds was able to get all my medical records, which is over 1,000 pages,” Ms. Reyes said. Dr. Berchuck reviewed and wrote his opinion in one week, recommending a hysterectomy because she was likely to have some residual cancer. “The same day, my treating physician, she called me to schedule a hysterectomy,” Ms. Reyes said.

Insurers are usually none too pleased with the employers’ use of alternatives: They’re reluctant to share information with an outside company and poised to undercut a potential competitor by offering a cheaper price. They may even refuse to work with some of the companies.

The largest employers push back. Fidelity Investments insists on cooperation between insurers and outsiders, said Jennifer Hanson, an executive at Fidelity Investments. “Those who don’t will be fired,” she said at a health business conference.

For Comcast, the next frontier is the financial well-being of its employees, many of whom live paycheck to paycheck and may not be able to afford even a small co-payment toward a doctor’s visit. Employees who run into financial trouble have no independent source of information, Mr. Spann said.

After talking to hundreds of companies, Comcast Ventures could not find a financial services start-up that would help employees without trying to sell them a product or earning their money on commissions. So Comcast recruited Mr. Spann to serve as chief executive of a new company, Brightside, that it created and invested in.

Employees who are less worried about their finances may be less likely to miss work or suffer from health problems, Mr. Leavitt said. Ultimately, he said, “there is a productivity play for Comcast.”