And the questions I’d ask UnitedHealth Group’s CEO about his company’s ACA pledge.

When I first saw the headline that UnitedHealth Group would “return Obamacare profits to customers in 2026,” my immediate reaction was: Oh good grief.

The timing is just too perfect.

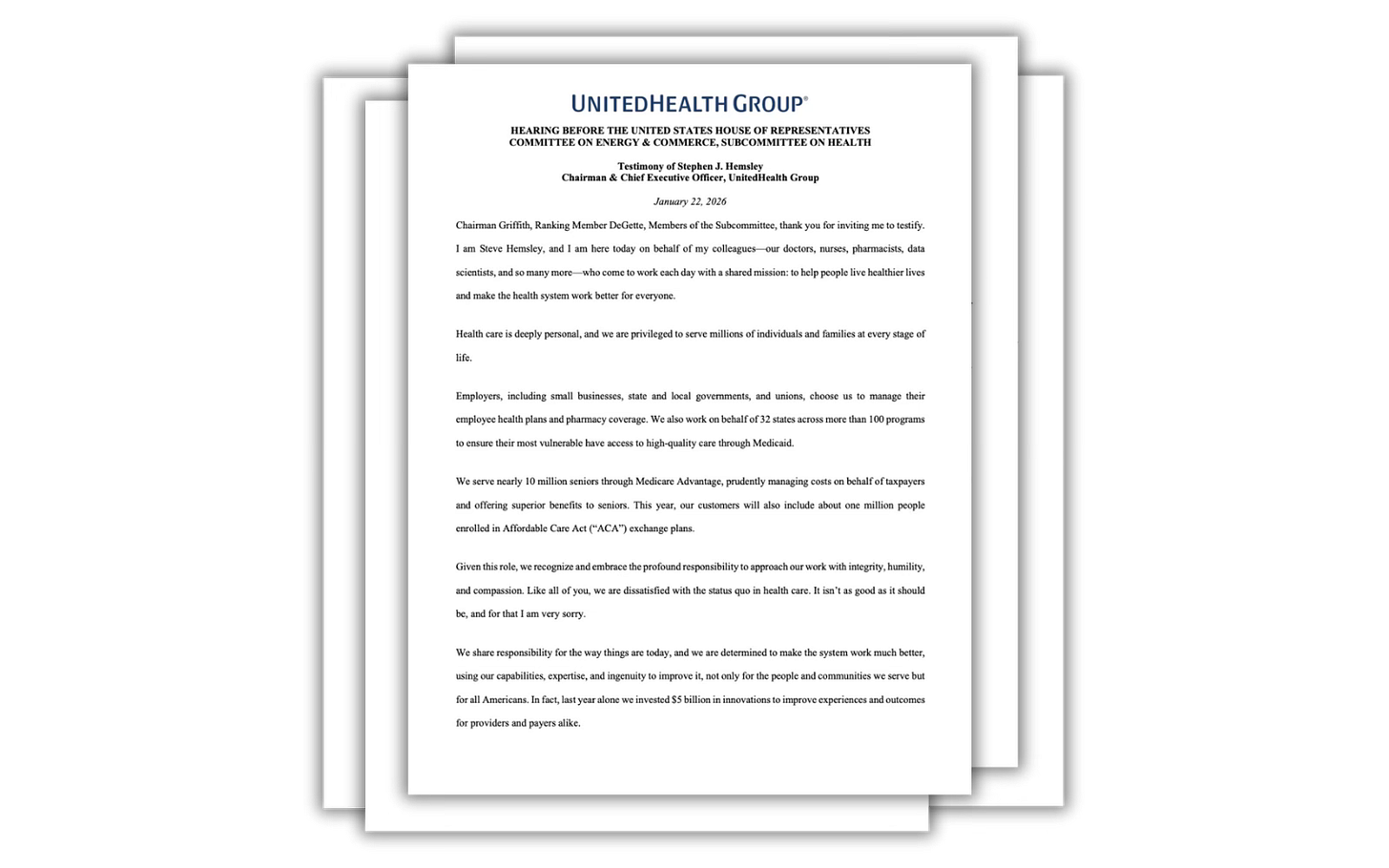

UnitedHealth’s pledge was tucked neatly into prepared testimony from CEO Stephen Hemsley, just hours before he (and four other Big Insurance CEOs) are to be hauled into Congress to testify before two House hearings on health care affordability.

Today, the CEOs will be asked to explain why Americans are paying through the nose for coverage and still getting denied care, trapped in narrow networks and buried under medical debt. As of late, Republican lawmakers — and President Trump himself — have discovered religion on the issue, publicly fuming about high premiums and insurer abuses.

If you’re feeling a little misty-eyed about this sudden burst of corporate altruism, let me save you the trouble. This isn’t a moral awakening. It’s a PR maneuver and narrative control being implemented in real time.

Hail Mary

It’s the corporate version of a quarterback, down by four points, seconds left on the clock, closing his eyes and launching the ball fifty yards downfield, hoping something — anything — miraculous happens before the time runs out. UnitedHealth’s pledge is just a long, desperate PR pass into the end zone, praying lawmakers and reporters will focus on the gesture instead of the business model that allows them to gobble up those dollars in the first place.

It’s worth noting that UnitedHealthcare, while the largest insurer in the country with 50 million health plan enrollees, is actually a relatively small player in the ACA marketplace — about 1 million customers in 2026, compared with roughly 6 million for Centene, according to Politico. This is not UnitedHealth sacrificing a part of its core profit engine. (It doesn’t even disclose how much it makes on its ACA business, but I can assure you it’s a very small part of the more than $30 billion in annual profits it’s been making in recent years.) This is a carefully calibrated concession of a slice of this conglomerate’s business that won’t jeopardize its Wall Street standing, which is what Hemsley cares about most.

As I wrote yesterday, I spent years inside the insurance industry, helping executives shape their public image and get ahead of bad headlines. I know this playbook by heart. When scrutiny spikes, you roll out a “good guy” story. You announce a consumer-friendly initiative and you flood the zone with talking points. You give lawmakers anything they can point to as evidence of “progress,” so the temperature in the room drops just a few degrees. It’s all an optics game, and if I was in my old job I’d probably get a bonus for thinking of a stunt like this.

Reputational damage control

When Hemsley and his Big Insurance buddies sit before Congress, don’t be surprised if he pivots quickly from this show of supposed humility to pointing fingers at everyone else for driving up costs – including hospitals, doctors, drug companies and whoever else. How do I know this? Hemsley said as much in his prepared testimony. His fellow CEOs sang from the exact same hymnbook, written by the best flacks money can buy.

So no, I’m not impressed by UnitedHealth Group’s gesture. And neither should lawmakers.

If UnitedHealth and its peers were serious about affordability, they wouldn’t be waiting until the night before a congressional grilling to dangle a symbolic rebate. They would be opening their books and explaining their pricing algorithms. They’d come clean about how much of our premium dollar goes to care and how much goes to executive compensation, stock buybacks and acquisitions that tighten their grip on the health care system.

This isn’t a gift. It’s a distraction.

And like most Hail Marys, it doesn’t work if you’re already down a whole lot of points. I hope the lawmakers at today’s hearing remember the score.

In light of UnitedHealth Group’s latest move, see below for some questions that I would ask Hemsley if I were in Congress:

- ACA plan and pledge specifics

- How many people are enrolled in your ACA marketplace plans, and how much total profit are you committing to rebate to them?

- What were your profits from ACA marketplace plans in recent years?

- Will you commit to disclosing ACA-specific enrollment and profit figures when you announce 2025 earnings next Tuesday? And how many people dropped coverage after the enhanced ACA subsidies were not renewed?

- By how much, on average, did you raise ACA premiums because Congress did not renew those subsidies?

- Public money vs. private plans

- Between 2020–2024, your filings show about $140 billion in operating profits and roughly $894 billion in revenue from Medicare and Medicaid versus $321 billion from commercial plans. Do you agree that about 74% of your revenue now comes from taxpayers and seniors?

- Given that you have about twice as many people in commercial plans as in Medicare/Medicaid, do you agree the government is paying you far more per enrollee than private customers are?

- Accountability going forward

- Will you commit to disclosing ACA-specific enrollment and profit figures when you announce 2025 earnings next Tuesday?

- Will you commit not to raise premiums or fees in your other lines of business to offset the ACA rebates?

- Will you commit to providing the transparency and granularity needed for the public to verify that this rebate pledge is real and not a PR maneuver?