Yesterday aboard Air Force One, President Trump was asked by a reporter if he supported Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Mike Crapo’s (R-IN) new health care proposal, which would authorize $1,500 deposits in Health Saving Accounts (HSAs) for lower-income individuals to replace the expiring Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies. The president’s response to the question was telling. And it shows just how much Big Insurance has fallen from grace in recent months.

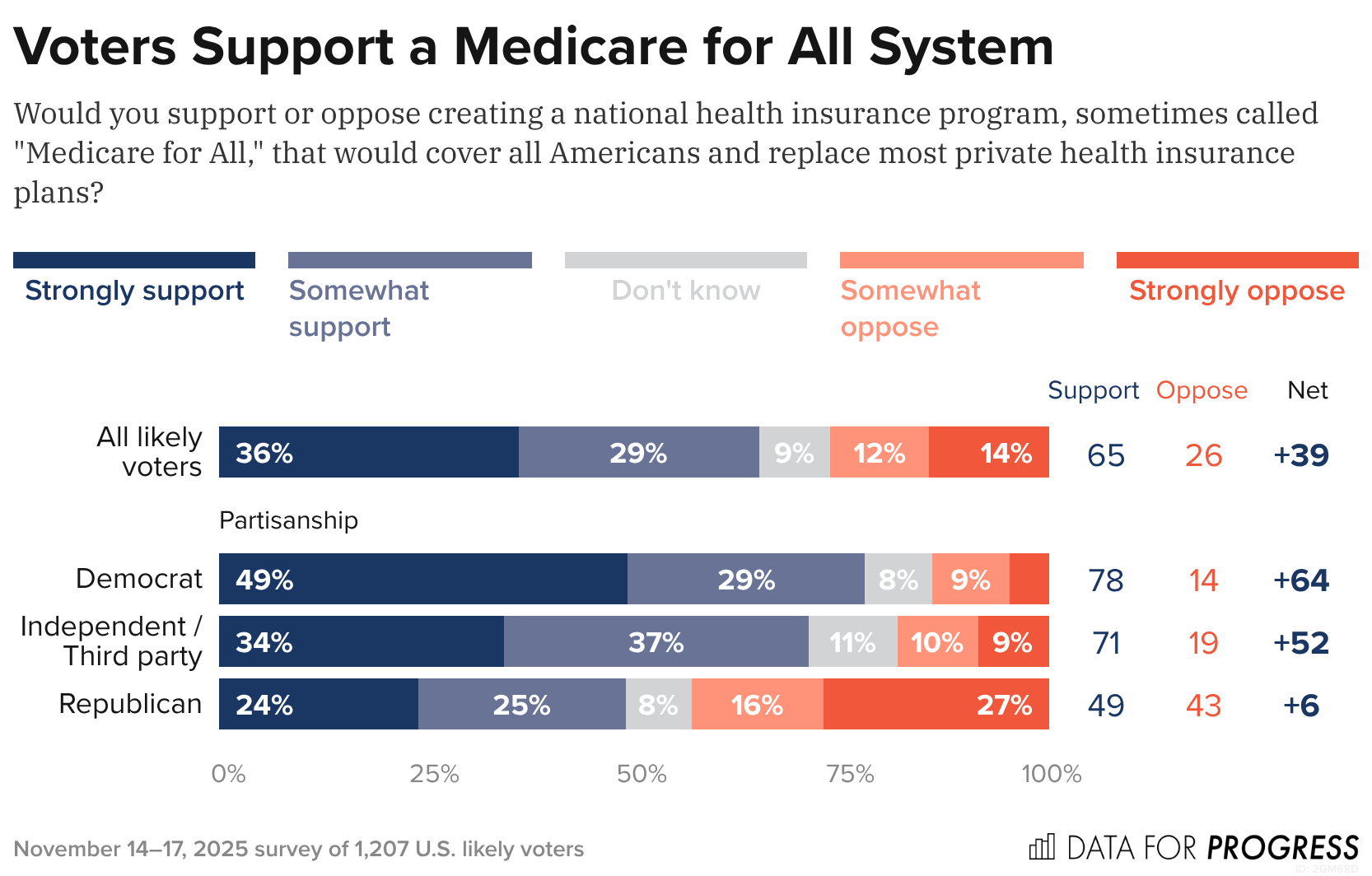

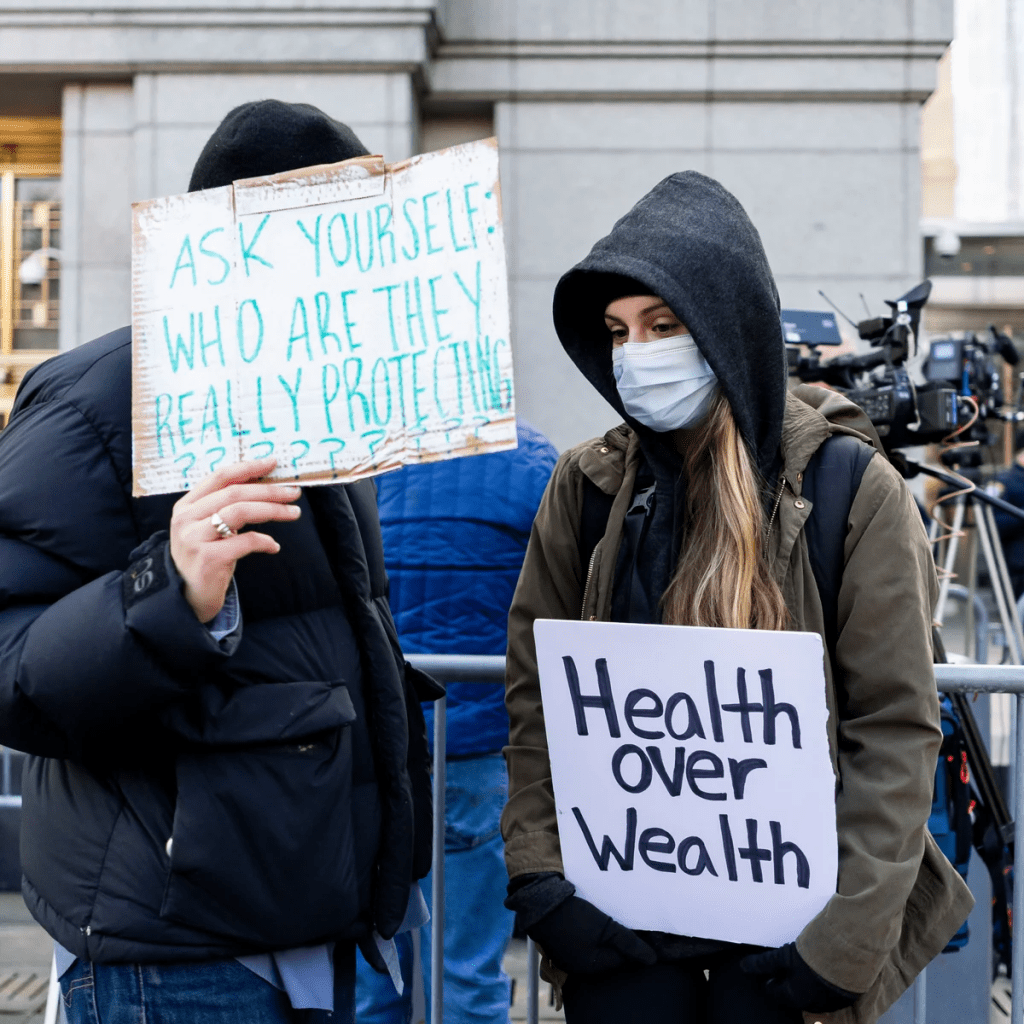

For decades, merely expressing disenchantment with private health insurers could get you labeled as a socialist. Now we are seeing daily criticism of health insurance companies from people across the political spectrum, leading one to not know if a quote like “Americans are getting crushed by health insurance with monthly payments” is coming from a progressive, like AOC, or a conservative like MTG. (Hint: that quote was from MTG). Trump’s response was in the same vein and could lead one to believe there is a chance of the left and right finding common ground in holding insurance companies accountable for their greed.

Where Trump is right. Where Trump is wrong.

Below we will dissect the president’s response and explain where he’s right and wrong.

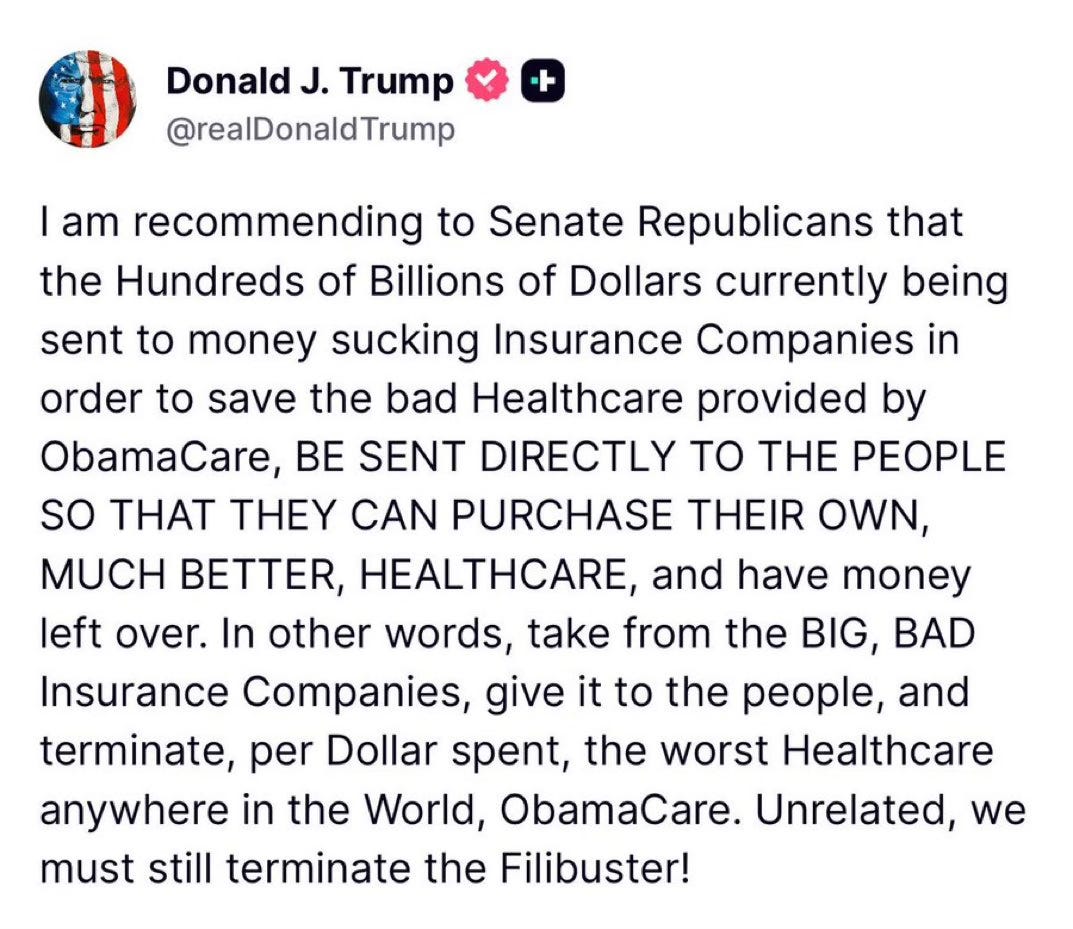

“I like the concept [of the Cassidy-Crapo legislation]. I don’t want to give the insurance companies any money. They’ve been ripping off the public for years.“

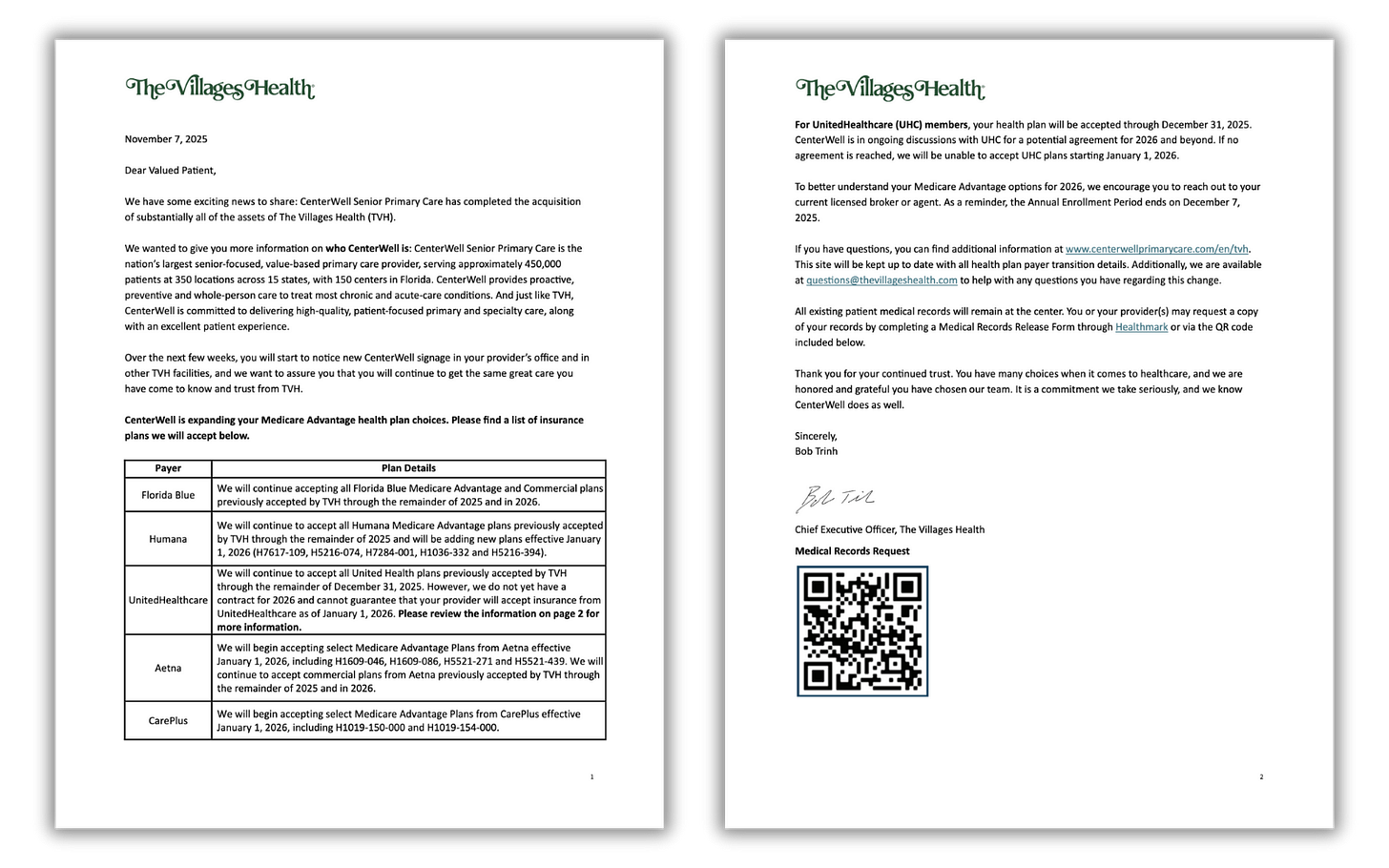

This is true. Big Insurance has been ripping us off for years. And almost all of insurers’ growth in recent years has come from us as taxpayers. Most big insurers now make far more money on the lucrative Medicare Advantage business and managing state Medicaid programs than from their commercial health insurance plans. And they’ve even figured out how to bilk the VA. UnitedHealthcare, the biggest insurer, now gets more than 75% of its revenues from taxpayer-funded programs. And yes, insurers are getting hundreds of billions of dollars every year from the ACA subsidies that are at the center of debate in Washington.

Here are a couple of examples. Private health insurers took in over $500 billion in tax dollars to administer Medicaid in 2023. And this year alone, they will be overpaid – yes overpaid – $85 billion as a consequence of how they’ve rigged the Medicare Advantage program.

Insurers also take in massive amounts of money in the form of premiums that people pay thinking that money goes to care. Much of that money ends up going toward things (and people) that do nothing to get us well or keep us well. Since 2014, the seven largest insurers have made over $500 billion in profits, and they used $146 billion to buy back their own stock. So yes, Trump is correct, health insurance companies have been ripping people off for years.

“Obamacare is a scam to make the insurance companies rich.”

No, Mr. President, the ACA is not a scam and most Americans now know that it has done a lot of good for a lot of people. Among other things, it made it possible for millions of people who previously had been blackballed by insurers because of a preexisting condition to finally get coverage. It brought us many long-overdue consumer protections, outlawed junk insurance, enabled young people to stay on their parents policies until they turned 26, alleviated job-lock through the creation of the ACA (Obamacare) marketplaces, and it made millions more low-income families eligible for Medicaid.

But, the president is right to say that Big Insurance has gotten rich since the passage of the ACA. Between 2014 (the year the entirety of the ACA was implemented) and 2024, just seven for-profit health insurers amassed $543.4 billion in profits and took in a staggering $10.192 trillion in revenues.

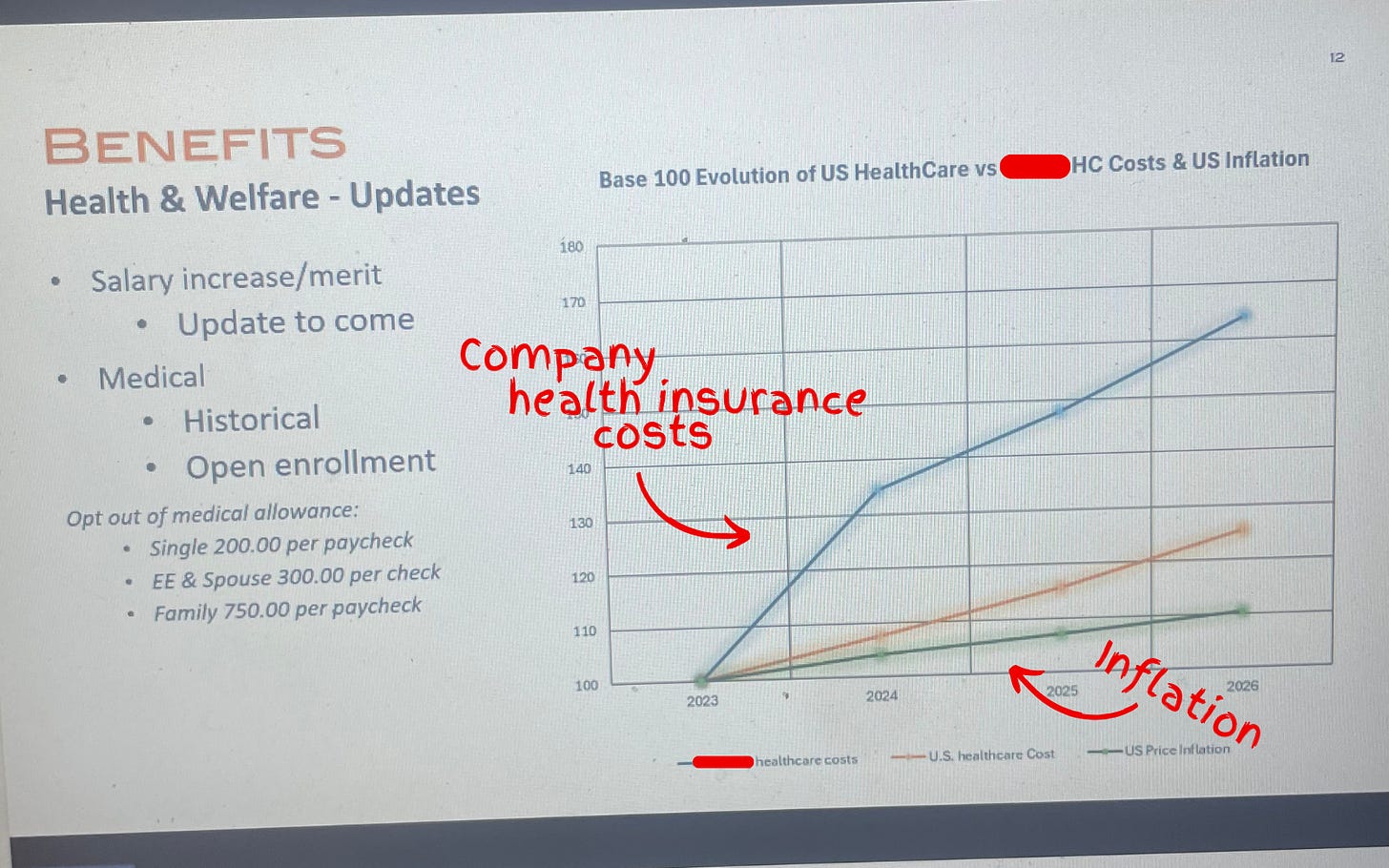

“And they have made, I mean, you look, $1,400 to $1,700 increase, 100 percent increase over the last number of years. There’s really few things that have gone up like insurance companies.”

The president is kind of right. As KFF reports, the cost of a family policy has increased 60% since 2014 – a rate of increase much higher than general inflation and also higher than medical inflation. And as we’ve published previously, not only has the total cost of an employer-sponsored plan skyrocketed, so has the share of premiums workers must pay. This year, employers deducted an average of $6,850 from their workers’ paychecks for family coverage, up from $4,823 in 2014. And keep in mind, all that money our employers are having to send to insurance companies is not money that’s available to give raises to workers or hire more people.

“They’re getting numbers and money like nobody’s ever seen before. Billions and billions of dollars is paid directly to insurance companies. We’re not going to do that anymore.”

The president is right. Several Big Insurance companies have ballooned in size over the past decade to become some of the world’s biggest corporate conglomerates. UnitedHealth Group, CVS/Aetna and Cigna are now numbers 3, 5 and 13 on the Fortune 500 list. The only American companies that take in more revenue than UnitedHealth are Walmart and Amazon.

“I believe Obamacare was set up to take care of insurance companies, not to take care of the American public.”

The president has his history wrong here. While there are plenty of Monday-morning-quarterbacking you can do for the ACA – the law was not passed to “take care of insurance companies.” While the ACA didn’t fix everything – not by a long shot – it did stop some of the insurance industry’s worst abuses, like refusing to sell policies to people with preexisting conditions – even acne – and “rescinding” policies to avoid paying for life-saving care. Some insurers were found to be paying employees bonuses to find policies to rescind, including the policies of women almost immediately after being diagnosed with breast cancer.

It prohibited health insurers from charging people more because of a preexisting condition and from dumping the sick so they could reward their shareholders more generously. Keep in mind that insurers consider every claim they pay as a loss, hence the term “medical loss ratio” (MLR), which the ACA addressed by requiring insurers to spend at least 80%-85% of our premiums on our health care.

And it’s not like Big Insurance wanted the ACA to pass. Back in 2010, America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), the PR and lobbying group for health insurers, quietly funneled $100 million to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to orchestrate a PR, advertising and lobbying blitz to keep the ACA from being passed.

While big health insurance companies have only grown since the passage of the ACA, it has been Big Insurance’s corporate maneuvers and work on Capitol Hill (not the law itself) that has allowed these companies to flout some of the ACA’s regulations and bend the law to do their will.

“I love the idea of money going directly to the people, not to the insurance companies. Going directly to the people. It could be in the health savings account. It could be a number of different ways.”

While that is a compelling sound bite, it’s disingenuous. The money proposed by Cassidy and Crapo to go to HSAs would then be used by enrollees to buy insurance, thus still giving money to the insurance companies. Even worse, the proposed amount of money to go to people’s HSAs to help them pay for health insurance and care is $1,000-$1,500. This is money that would be used to purchase a bronze or copper plan with a high deductible (with many of those plans having deductibles north of $5,000). That means under this plan people would still need to come up with thousands to meet their deductible on top of paying their premiums every month. $1,000 wouldn’t come close to even covering the premiums for a decent policy, much less the out-of-pocket costs.

Replacing ACA subsidies with HSAs would still keep Americans tied to the same private health insurers that Trump calls “big, bad” and “money-sucking.” Most families would still be exposed to crippling medical bills, and even more tax dollars would flow to insurance conglomerates that own HSA custodian businesses (like UnitedHealth’s Optum Bank).

“And the people go out and buy their own insurance, which can be really much better health insurance, health care.”

That’s wishful thinking far removed from reality. The health insurance plans available to people who get money for their HSAs under the Cassidy-Crapo proposal – rather than getting subsidies – are the same as those currently available. Worse, without the subsidies, people will not be able to afford the gold or silver plans that have lower out-of-pocket costs. In reality the plans that people buy under the proposed Cassidy-Crapo plan would have less value than the plans they previously bought with subsidies.

Trump’s comments are coming ahead of tomorrow’s scheduled vote in the Senate on dueling Democratic and Republican proposals to deal with the enhanced subsidies for ACA plans that will expire in three weeks. Without those subsidies, premiums will spike for many of the 24 million American enrolled in “Obamacare” plans. Democrats want to extend the subsidies for three years. Republicans, led by Senate Majority Leader John Thune, will push a plan replacing those subsidies with direct payments into individuals’ Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), as the president is suggesting. Neither plan is expected to get the 60 votes required for passage. What happens next is anybody’s guess.