Health care costs hurt Californians every day. Millions can’t afford the care they need. More than half of all Californians skip or delay getting care because it costs too much.

How did we get here?

Health care is too expensive for people in large part because underlying costs in our health care system have grown unchecked for decades. Underlying costs are the “base ingredients” that determine how expensive health care is. Think of things like hospital operating costs, prescription drug prices, and doctor fees — when these costs go up year after year, they get passed on to patients through higher premiums, bigger deductibles, and larger medical bills.

The solution to the affordability crisis isn’t to slash health care spending across the board — that often makes things worse for patients. Instead, we need to be smart about cutting that 25% that doesn’t provide any value for patients.

Some of that rising cost has produced things we actually want, such as breakthrough treatments that save lives, cutting-edge medical equipment, or hospitals retrofitted to withstand earthquakes.

But around 25 cents of every dollar in our health care system doesn’t help patients get better care or become healthier. In 2020, it was estimated that this added up to as much as $73 billion dollars a year in California’s health care system. Where does that money go? The top three culprits are:

- Red tape, paperwork and other administrative waste

- Excessive profits for companies that can charge unfair prices because they have no, or not enough, competition

- Treating serious illnesses that could have been caught early or prevented altogether with basic primary care.

The solution to the affordability crisis isn’t to slash health care spending across the board — that often makes things worse for patients. Instead, we need to be smart about cutting that 25% that doesn’t provide any value for patients. Sometimes that might actually mean spending more money upfront, like making sure everyone can see a primary care doctor, to save money down the road by keeping people healthier.

This work is challenging, but it’s critical. Millions already can’t afford health care. If Californians’ health care costs keep rising the way they have been, even more families will be left behind.

The Problem and Why It Matters

Unchecked growth in the underlying costs of our health care system has driven total health care spending — from families, governments, employers and others combined — to more than triple since 2000, far outpacing inflation, economic growth, and wages.

Here are just a few key examples of the impact on California families:

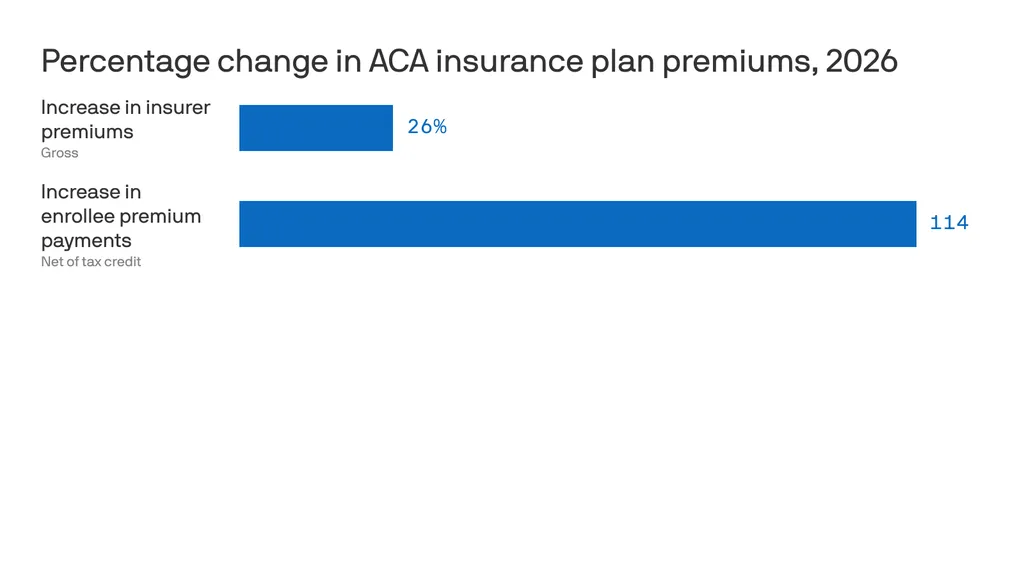

Health insurance is increasingly becoming unaffordable for California families.

- Over the last 20 years, health care premiums for job-based insurance have grown nearly twice as fast as wages in California. Deductibles have grown nearly three times as fast as wages.

- The average premium for a family health plan through job-based insurance in California was over $28,000 in 2025.

- Three out of four workers with single coverage through their employer had a deductible in 2025, averaging roughly $1,600. One in ten had a deductible of more than $3,000.

Families are skipping care or going into debt.

- More than half of all Californians (53%) skipped or delayed care in 2023 because it cost too much. For families with low incomes, that number jumps to 74%.

- Of those who skipped care, 54% say their health got worse.

- 38% of all Californians report carrying medical debt. For Californians with low incomes, that rises to 52%.

Overview of the 3 Reasons

1. Administrative Waste

Health care requires some office work — doctors and hospitals have to schedule appointments, send bills, and keep records. But in the U.S., we spend way too much time and money on administrative tasks, which does nothing to make care better for patients.

Why Does This Happen?

Our health care system is complex. Different hospitals, doctors, and insurance companies often all use different computer systems for clinical data, billing, and administrative tasks. They can’t easily share information with each other. This means:

- Staff in different parts of the system spend extra time entering the same information over and over;

- Insurance companies and hospitals have to hire more people just to handle paperwork; and

- Simple tasks become complicated and expensive.

How Much Money Gets Wasted?

Researchers in 2020 estimated that administrative waste cost the California health care system nearly $21 billion a year, making it the number one source of health care spending that doesn’t do anything to help patients or improve care.

How This Hurts Patients

Administrative waste doesn’t just cost money. It also hurts patient care:

- Doctors spend less time with patients because they’re busy with forms.

- Patients wait longer to get care.

- Doctors have to call insurance companies over and over to find out what’s covered, and this can delay treatment when people need help.

Take a deeper dive into Administrative Waste →

2. Unfair Pricing and Too Few Choices

Health care spending depends on two things: 1) how much care people get and 2) the prices that are charged for that care. In California, we have a big problem with pricing.

Same Care, Very Different Prices

The same medical procedure can cost wildly different amounts depending on where you go. For example, a knee replacement might cost $50,000 at one hospital and $70,000 at another. This happens even when both hospitals provide the same quality of care. In other words, the more expensive hospital is not necessarily better.

Lack of Competition Drives Prices Up and Hurts Patients

In many areas, there isn’t enough competition among health care organizations. For example, big hospital systems are buying up smaller hospitals. In some areas, there’s only one major hospital system left. Likewise, a few large insurance companies control most of the market. In some areas, one insurance company dominates.

When hospitals and insurance companies don’t have to compete:

- Prices can go up without any improvement in care quality.

- Patients have fewer choices about where to get care.

- Families pay more for the same treatment.

- Some areas become “take it or leave it” markets.

This creates unfair contracts where the biggest companies can demand high prices because patients have nowhere else to go.

Take a deeper dive into Unfair Pricing and Too Few Choices →

3. Not Enough Prevention in Health Care

When doctors find health problems early, they’re much easier and cheaper to treat. For example:

- Regular cancer screenings can find problems before they become serious cancer.

- Checking on people with heart problems can prevent expensive hospital stays.

- Treating diabetes early prevents costly complications later.

Too often, though, people don’t get these early checks because there might not be a primary care doctor that can see them when they need it. By the time they see a doctor, their problems are much more serious and expensive to fix.

We Don’t Spend Enough on Prevention

Most prevention happens when you visit your primary care doctor for regular check-ups and basic care. But the U.S. has a big problem: We spend only 5 cents of every health care dollar on primary care, while other wealthy countries spend three times that amount.

California research shows that when provider organizations spend more money on primary care:

- Patients get better quality care.

- People are happier with their treatment.

- Fewer people end up in the emergency room.

- Fewer people need expensive hospital stays.

- Overall health care costs go down.

We could save billions of dollars by helping people stay healthy instead of waiting until they get really sick. It’s like fixing a small leak in your roof instead of waiting until your whole ceiling falls down.

Take a deeper dive into Not Enough Prevention →

Solutions

The good news is that we can fix these problems. California is working on several smart solutions right now.

The Office of Health Care Affordability

Created in In 2022, the Office of Health Care Affordability (OHCA) aims to break the cycle of the last decades and make sure that underlying costs in the health care system don’t continue to spiral out of control year over year.

Cost Growth Targets

In 2024, OHCA set an important new target: Total spending by health care’s major players — like hospitals, insurance companies, and large medical groups — can’t increase by more than 3% each year. That’s roughly how much a typical California family’s income grows every year. The target will be implemented in phases over the next several years.

This creates a powerful new incentive for these health care organizations to manage their underlying costs, rather than allowing them to grow unchecked and passing on increases every year to patients. Over time, this should help make health care more affordable for families.

If a health care organization exceeds its spending growth target without a good reason, OHCA will take increasingly serious enforcement actions, starting with guidance to the company on how to meet the target all the way to financial penalties. Penalty money will go into a fund and then back to California families to help them pay for their health care.

Making Sure Quality Stays High

Spending caps are intended to target things like administrative inefficiencies and monopolies, not quality of care.

To ensure health care organizations are focusing in the right places, OHCA is charged with ensuring:

- Patients can still get the care they need.

- Care quality stays just as good.

- Hospitals and clinics have enough doctors and nurses.

OHCA is taking steps to address unfair pricing by reviewing health care mergers and acquisitions.