Most voters approached for this article declined to be interviewed, saying they didn’t understand the issue.

Betsy Foster and Doug Dillon are devotees of Josh Harder. The Democratic upstart is attempting to topple Republican incumbent Jeff Denham in this conflicted, semi-rural district that is home to conservative agricultural interests, a growing Latino population and liberal San Francisco Bay Area refugees.

To Foster’s and Dillon’s delight, Harder supports a “Medicare-for-all” health care system that would cover all Americans.

Foster, a 54-year-old campaign volunteer from Berkeley, believes Medicare-for-all is similar to what’s offered in Canada, where the government provides health insurance to everybody.

Dillon, a 57-year-old almond farmer from Modesto, says Foster’s description sounds like a single-payer system.

“It all means many different things to many different people,” Foster said from behind a volunteer table inside the warehouse Harder uses as his campaign headquarters. “It’s all so complicated.”

Across the country, catchphrases such as “Medicare-for-all,” “single-payer,” “public option” and “universal health care” are sweeping state and federal political races as Democrats tap into voter anger about GOP efforts to kill the Affordable Care Act and erode protections for people with preexisting conditions.

Republicans, including President Donald Trump, describe such proposals as “socialist” schemes that will cost taxpayers too much. They say their party is committed to providing affordable and accessible health insurance, which includes coverage for preexisting conditions, but with less government involvement.

Voters have become casualties as candidates toss around these catchphrases — sometimes vaguely and inaccurately. The sound bites often come across as “quick answers without a lot of detail,” said Gerard Anderson, a professor of public health at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School Public Health.

“It’s quite understandable people don’t understand the terms,” Anderson added.

For example, U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) advocates a single-payer national health care program that he calls Medicare-for-all, an idea that caught fire during his 2016 presidential bid.

But Sanders’ labels are misleading, health experts agree, because Medicare isn’t actually a single-payer system. Medicare allows private insurance companies to manage care in the program, which means the government is not the only payer of claims.

What Sanders wants is a federally run program charged with providing health coverage to everyone. Private insurance companies wouldn’t participate.

In other words: single-payer, with the federal government at the helm.

Absent federal action, Democratic gubernatorial candidates Gavin Newsom in California, Jay Gonzales in Massachusetts and Andrew Gillum in Florida are pushing for state-run single-payer.

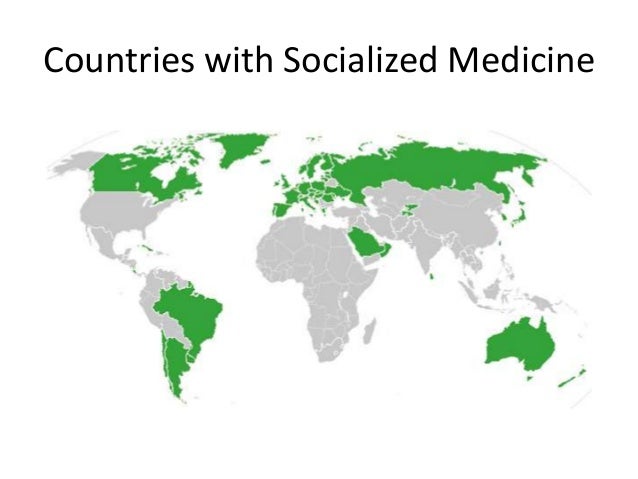

To complicate matters, some Democrats are simply calling for universal coverage, a vague philosophical idea subject to interpretation. Universal health care could mean a single-payer system, Medicare-for-all or building upon what exists today — a combination of public and private programs in which everyone has access to health care.

Others call for a “public option,” a government plan open to everyone, including Democratic House candidates Antonio Delgado in New York and Cindy Axne in Iowa. Delgado wants the public option to be Medicare, but Axne proposes Medicare or Medicaid.

Are you confused yet?

Sacramento-area voter Sarah Grace, who describes herself as politically independent, said the dialogue is over her head.

“I was a health care professional for so long, and I don’t even know,” said Grace, 42, who worked as a paramedic for 16 years and now owns a holistic healing business. “That’s telling.”

In fact, most voters approached for this article declined to be interviewed, saying they didn’t understand the issue. “I just don’t know enough,” Paul Her of Sacramento said candidly.

“You get all this conflicting information,” said Her, 32, a medical instrument technician who was touring the state Capitol with two uncles visiting from Thailand. “Half the time, I’m just confused.”

The confusion is all the more striking in a state where the expansion of coverage has dominated the political debate on and off for more than a decade. Although the issue clearly resonates with voters, the details of what might be done about it remain fuzzy.

A late-October poll by the Public Policy Institute of California shows the majority of Californians, nearly 60 percent, believe it is the responsibility of the federal government to make sure all Americans have health coverage. Other state and national surveys reveal that health care is one of the top concerns on voters’ minds this midterm election.

Democrats have seized on the issue, pounding GOP incumbents for voting last year to repeal the Affordable Care Act and attempting to water down protections for people with preexisting medical conditions in the process. A Texas lawsuit brought by 18 Republican state attorneys general and two GOP governors could decimate protections for preexisting conditions under the ACA — or kill the law itself.

Republicans say the current health care system is broken, and they have criticized the rising premiums that have hit many Americans under the ACA.

Whether the Democratic focus on health care translates into votes remains to be seen in the party’s drive to flip 23 seats to gain control of the House.

The Denham-Harder race is one of the most watched in the country, rated too close to call by most political analysts. Harder has aired blistering ads against Denham for his vote last year against the ACA, and he sought to distinguish himself from the incumbent by calling for Medicare-for-all — an issue he hopes will play well in a district where an estimated 146,000 people would lose coverage if the 2010 health law is overturned.

Yet Harder is not clinging to the Medicare-for-all label and said Democrats may need to talk more broadly about getting everyone health care coverage.

“I think there’s a spectrum of options that we can talk about,” Harder said. “I think the reality is we’ve got to keep all options open as we’re thinking towards what the next 50 years of American health care should look like.”

To some voters, what politicians call their plans is irrelevant. They just want reasonably priced coverage for everyone.

Sitting with his newspaper on the porch of a local coffee shop in Modesto, John Byron said he wants private health insurance companies out of the picture.

The 73-year-old retired grandfather said he has seen too many families struggle with their medical bills and believes a government-run system is the only way.

“I think it’s the most effective and affordable,” he said.

Linda Wahler of Santa Cruz, who drove to this Central Valley city to knock on doors for the Harder campaign, also thinks the government should play a larger role in providing coverage.

But unlike Byron, Wahler, 68, wants politicians to minimize confusion by better defining their health care pitches.

“I think we could use some more education in what it all means,” she said.