Last Thursday, Seattle-based Providence Health System announced it is refunding nearly $21 million in medical bills paid by low-income residents of Washington and erasing $137 million more in outstanding debt for others. Other systems are likely to follow as pressure con mounts on large, not-for-profit systems to modify their business practices in sensitive areas like patient debt collection, price transparency, executive compensation, investment activities and others.

Not-for profit systems control the majority of the 2,987 nongovernment not-for-profit community hospitals in the U.S. Some lawmakers think it’s time to revisit to revisit the tax exemption. It has the attention of the American Hospital Association which lists “protecting not-for-profit hospitals’ the tax-exempt status” among its 15 Advocacy Priorities in 2024 (it was not on their list in 2023).

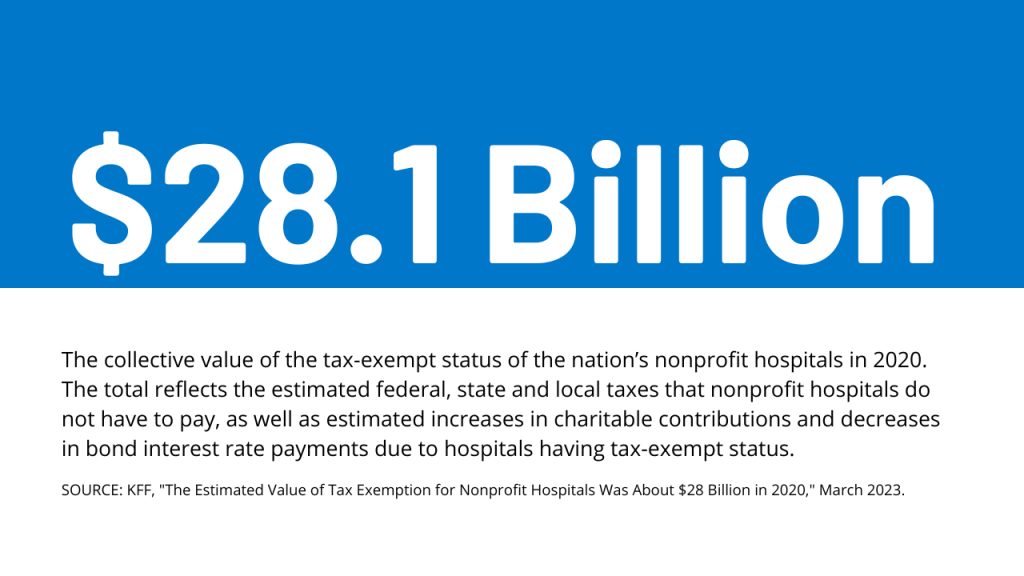

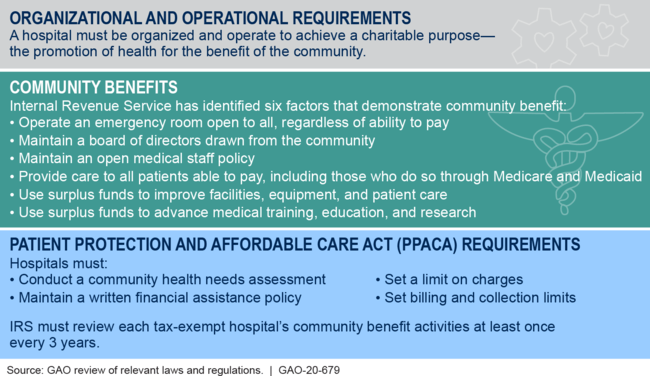

Background: Per a recent monograph in Health Affairs: “The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) uses the Community Benefit Standard (CBS), a set of 10 holistically analyzed metrics, to assess whether nonprofit hospitals benefit community health sufficiently to justify their tax-exempt status. Nonprofit hospitals risk losing their tax exemption if assessed as underinvesting in improving community health. This exemption from federal, state, and local property taxes amounts to roughly $25 billion annually.

However, accumulating evidence shows that many nonprofit hospitals’ investments in community health meet the letter, but not the spirit, of the CBS.

Indeed, a 2021 study showed that for every $100 in total expenses nonprofit hospitals spend just $2.30 on charity care (a key component of community benefit)—substantially less than the $3.80 of every $100 spent by for-profit hospitals. A 2022 study looked at the cost of caring for Medicaid patients that goes unreimbursed and is therefore borne by the hospital (another key component of community benefit); the researchers found that nonprofit hospitals spend no more than for-profit hospitals ($2.50 of every $100 of total expense).”

In its most recent study, the AHA found the value of CBS well-in-excess of the tax exemption by a factor of 9:1. But antagonism toward the big NFP systems has continued to mount and feelings are intense…

- Insurers think NFP systems exist to gain leverage in markets & states over insurers in contract negotiations and network design. They’ll garner support from sympathetic employers and lawmakers, federal anti-consolidation and price transparency rulings and in the court of public opinion where frustration with the system is high.

- State officials see the mega- NFP systems as monopolies that don’t deserve their tax exemptions while the state’s public health, mental health and social services programs struggle.

- Some federal lawmakers think the NFP systems are out of control requiring closer scrutiny and less latitude. They think the tax exemption qualifiers should be re-defined, scrutinized more aggressively and restricted.

- Well-publicized investments by NFP systems in private equity backed ventures has lent to criticism among labor unions and special interests that allege systems have abandoned community health for Wall Street shareholders.

- Investor-owned multi-hospital operators believe the tax exemption is an unfair advantage to NFPs while touting studies showing their own charity care equivalent or higher.

- Other key NFP and public sector hospital cohorts cry foul: Independent hospitals, academic medical centers, safety-net (aka ‘essential’) hospitals, rural health clinics & hospitals, children’s hospitals, rural health providers, public health providers et al think they get less because the big NFPs get more.

- And the physicians, nurses and workforces employed by Big NFP systems are increasingly concerned by systemization that limits their wages, cuts their clinical autonomy and compromises their patients’ health.

My take:

The big picture is this: the growth and prominence of multi-hospital systems mirrors the corporatization in most sectors of the economy: retail, technology, banking, transportation and even public utilities. The trifecta of community stability—schools, churches and hospitals—held out against corporatization, standardization and franchising that overtook the rest. But modernization required capital, the public’s expectations changed as social media uprooted news coverage and regulators left doors open for “new and better” that ceded local control to distant corporate boards.

Along the way, investor-owned hospitals became alternatives to not-for-profits, and loose networks of hospitals that shared purchasing and perhaps religious values gave way to bigger multi-state ownership and obligated groups.

The attention given large NFP hospital systems like Providence and others is not surprising. These brands are ubiquitous. Their deals with private equity and Big Tech are widely chronicled in industry journalism and passed along in unfiltered social media. And their collective financial position seems strong: Moody’s, Fitch, Kaufman Hall and others say utilization has recovered, pandemic recovery is near-complete and, despite lingering concerns about workforce issues, growth in their core businesses plus diversification in new businesses are their foci. (See Hospital Section below).

I believe not-for-profit hospital systems are engines for modernizing health delivery in communities and a lightening rod for critics who think their efforts more self-serving than for the public good.

Most consumers (55%) think they earn their tax exemption but 34% have mixed feelings and 10% disagree. (Keckley Poll November 20, 2023). That’s less than a convincing defense.

That’s why the threat to the tax exemption risk is real, and why every organization must be prepared. Equally important, it’s why AHA, its state associations and allies should advance fresh thinking about ways re-define CBS and hardwire the distinction between organizations that exist for the primary purpose of benefiting their shareholders and those that benefit health and wellbeing in their communities.

PS: Must reading for industry watchers is a new report from by Health Management Associates (HMA) and Leavitt Partners, an HMA company, with support from Arnold Ventures. The 70-page report provides a framework for comparing the increasingly crowned field of 120 entities categorized in 3 groups: Hybrids (6.9 million), Delivery (5.8 million) and Enablers 17.5 million

“At the start of the movement, value-based arrangements primarily involved traditional providers and payers engaging in relatively straight-forward and limited contractual arrangements. In recent years, the industry has expanded organically to include a broader ecosystem of risk-bearing care delivery organizations and provider enablement entities with capabilities and business models aligned with the functions and aims of accountable care…Inclusion criteria for the 120 VBD entities included in this analysis were:

- 1-Serve traditional Medicare, MA, and/or Medicaid populations. Entities that are focused solely on commercial populations were excluded

- 2-Operate in population-based, total cost of care APMs—not only bundled payment models.

- 3- Focus on primary care and/or select specialties that are relevant to total cost of care models (i.e., nephrology, oncology, behavioral health, cardiology, palliative care). Those exclusively focused on specialty areas geared toward episodic models (e.g., MSK) were excluded. –

- 4-Share accountability for cost and quality outcomes. Business models must be aligned with provider performance in total cost of care arrangements. Vendors that support VBP but do not share accountability for outcomes were excluded.

HMA_VBP-Entity-Landscape-Report_1.31.2024-updated.pdf (healthmanagement.com) February 2024