Academic medicine combines healthcare with higher education, the two sectors of the American economy that have exhibited outsized cost growth during the past 50 years. The result is a stunning disconnection between the business practices of academic medical centers (AMCs) and the supply-demand dynamics reshaping healthcare delivery.

Market, technological and regulatory forces are pushing the healthcare industry to deliver higher-value care that generates better outcomes at lower costs. A parallel movement is shifting resources out of specialty and acute care services into primary, preventive, behavioral health and chronic disease care services. In the process, care delivery is decentralizing and becoming more consumer-centric.

AMCs Double Down

Counter to these trends, academic medicine is doubling down on high-cost, centralized, specialty-focused care delivery. Privilege has its price. Several AMCs — including Mass General Brigham, IU Health, UCSF, Ohio State and UPMC — are undertaking multibillion-dollar expansions of their existing campuses. Collectively, AMCs expect American society to fund their continued growth and profitability irrespective of cost, effectiveness and contribution to health status.

Despite being tax-exempt and having access to a large pool of free labor (residents), AMCs charge the highest treatment prices in most markets. [1] Archaic formulas allocate residency “slots” and lucrative Graduate Medical Education payments (over $20 billion annually) disproportionately into specialty care and more-established AMCs. Given their cushy funding arrangements, it’s no wonder AMCs fight vigorously to maintain an out-of-date status quo.

Legacy practices from the early 1900s still dominate medical education, medical research and clinical care. Like tenured faculty, academic physicians manage their practices with little interference. Clinical deans rule their departments with a free hand. With few exceptions, interdisciplinary coordination is an oxymoron. The result is fragmented care delivery that tolerates duplication, medical error and poor patient service.

Irresistible consumerism confronts immovable institutional inertia. As exhibited by substantial operating losses at many AMCs, their foundations are beginning to crack. [2]

Medicine’s Rise from Poverty to Prosperity

In his 1984 Pulitzer Prize-winning work, Paul Starr chronicles the social transformation of American medicine during the 19th and 20th centuries. Prior to the 1900s, doctors had low social status. Most care took place in the home. Pay was low. The profession lacked professional standards. There were too many quacks. Most doctors lived hand-to-mouth.

As the century turned, several cultural, economic, scientific and legal developments converged to elevate the profession’s status in American society. Stricter licensing reduced the supply of physicians and closed most existing medical schools. Legislation and legal rulings restricted corporate ownership of medical practices and enshrined physicians’ operating autonomy. Scientific breakthroughs gave medicine more healing power.

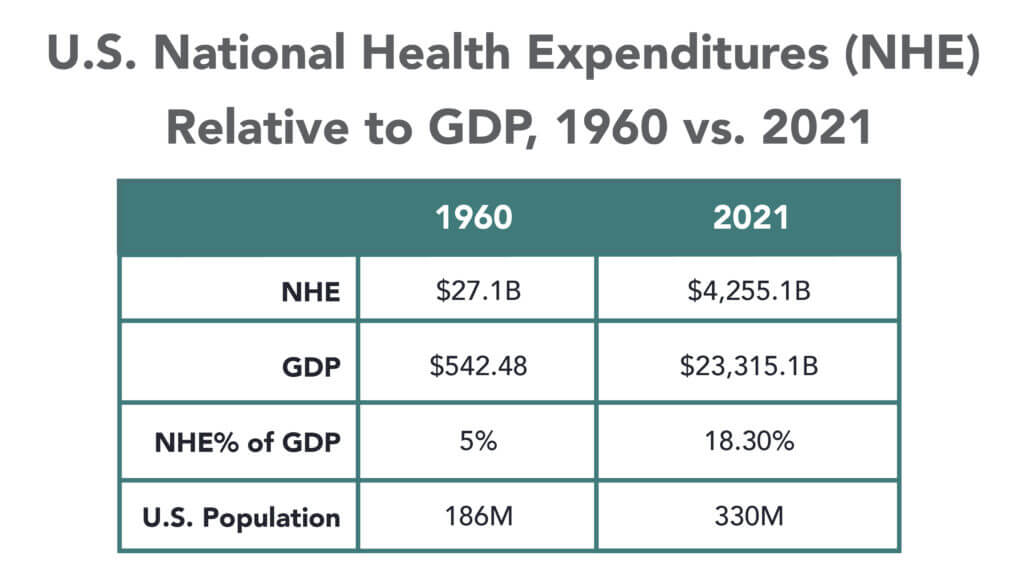

Through the decades that followed, the American Medical Association and state medical societies frustrated external attempts to control medical delivery externally and institute national health insurance. They insisted on fee-for-service payment and the absolute right of patients to choose their doctors. These are causal factors underlying healthcare’s skyrocketing cost increases, growing from 5% of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in 1960 to over 18% in 2021.

Academic and community-based physicians have always had a tenuous relationship. Status and prestige accompany academic affiliations. Academic practices require referrals from community physicians but rarely consult with them on treatment protocols. For their part, community physicians marvel at the lack of market awareness exhibited by academic practices. They have tolerated one another to perpetuate collective physician control over healthcare operations.

Incomes and prestige for both community and academic physicians rose as the medical profession limited practitioner supply, established payment guidelines, encouraged specialization, controlled service delivery and socialized capital investment. One hundred years later, the business of healthcare still exhibits these characteristics. Gleaming new medical centers testify to the profession’s success in socializing capital investment and maintaining autonomy over hospital operations.

Entrenched beliefs and behaviors explain why most hospitals, despite their high construction costs, are largely deserted after 4 p.m. and on weekends. They explain the maldistribution of facilities and practitioners. They explain the overdevelopment of specialty care. They explain the underinvestment in preventive care, mental health services and public health.

Value-Focused Backlash Portends Reckoning

These beliefs and behaviors are contributing to AMC’s current economic dislocation. Dependent upon public subsidies and premium treatment payments to maintain financial sustainability, high-cost AMCs are particularly vulnerable to value-based competitors.

The marketplace is attacking inefficient clinical care with tech-savvy, consumer-friendly business models. Care delivery is decentralizing even as many AMCs invest more heavily in campus-based medicine. A market-based reckoning confronts academic medicine.

A visit up north illustrates the general unwillingness of academic physicians to accept market realities and their continued insistence on maintaining full control over the academic medical enterprise. It’s like watching a train wreck occur in slow motion.

Minnesota Madness

After experiencing severe economic distress, the University of Minnesota sold its University of Minnesota Medical Center (UMMC) to Fairview Health in 1997. Fairview currently operates UMMC in partnership with the University of Minnesota Physicians (UMP) under the banner of M Health Fairview.

In September 2022, Sanford Health and Fairview Health signed a letter of intent to merge. The new combined company would bear the Sanford name with its headquarters in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Despite the opportunity to double its catchment area for specialty referrals, the University and UMP oppose the merger with Sanford. They fear out-of-state ownership could compromise the integrity of UMMC’s operations.

Fairview wants the Sanford merger to help it address massive operating losses resulting, in part, from its contractual arrangements with UMP. Negotiations between the parties have become acrimonious. Amid the turmoil, the University and UMP announced in January 2023 their intention to acquire UMMC from Fairview and build a new state-of-the-art medical center on the University’s Minneapolis campus.

The University has named this proposal “MPact Health Care Innovation.” It calls for the Minnesota state legislature to fund the multibillion-dollar cost of acquiring, building and operating the new medical enterprise. Typical of academic medical practices, UMP expects external sources to pony up the funding to support their high-cost centralized business model while they continue to call the shots.

The arrogance and obliviousness of the University’s proposal is staggering. Minnesota struggles with rising rates of chronic disease and inequitable healthcare access for low-income urban and rural communities. The idea that a massive governmental investment in academic medicine will “bridge the past and future for a healthier Minnesota” as the MPact tagline proclaims is ludicrous.

Out of Touch

Like the rest of the country, Minnesota is experiencing declining life expectancy. Despite spending more than double the average per-capita healthcare cost of other wealthy countries, the United States scores among the worst in health status measures. Spending more on high-end academic medicine won’t change these dismal health outcomes. Spending more on preventive care, health promotion and social determinants of health could.

The real gem in the University of Minnesota’s medical enterprise is its medical school. It has trained 70% of the state’s physicians. It ranks third and fourth nationally in primary care and family medicine. It is advancing a progressive approach to interdisciplinary and multi-professional care.

If the Minnesota state legislature really wants to advance health in Minnesota, it should expand funding for the University’s aligned health schools and community-based programs without funding the acquisition and expansion of the University’s clinical facilities.

No Privilege Without Performance

Our nation must stop enabling academic medicine’s excesses. Funding AMCs’ insatiable appetite for facilities and specialized care delivery is counterproductive. It is time for academic medicine to embrace preventive health, holistic care delivery and affordable care access.

Privilege comes with responsibility. AMCs that resist the pivot to value-based care and healthier communities deserve to lose market relevance.

America has the means to create a healthier society. It requires shifting resources out of healthcare into public health. We must have the will to make community-based health networks a reality. It starts by saying no to needless expansion of acute care facilities.