In 46 states, once you choose Medicare Advantage at 65, you can almost never leave.

Medicare was founded in 1965 to end the crisis of medical care being denied to senior citizens in America, but private insurers have been able to progressively expand their presence in Medicare.

One of the biggest selling points of Obamacare was that it would finally end discrimination against patients on the basis of pre-existing conditions.

But for one vulnerable sector of the population, that discrimination never ended. Insurers are still able to deny coverage to some Americans with pre-existing conditions. And it’s all perfectly legal.

Sixty-five million seniors are in Medicare open enrollment from October 15 until December 7. Nearly 32 million of those patients are enrolled in Medicare Advantage, a set of privately run plans that have come under fire for denying treatment and overbilling the government.

Medicare Advantage patients theoretically have the option to return to traditional Medicare. But in 46 states, it is nearly impossible for those people to do so without exposing themselves to great financial risk.

Traditional Medicare has no out-of-pocket cap and covers 80 percent of medical expenses. Unlike Medicare Advantage plans, in traditional Medicare, seniors can choose whatever provider they want, and coverage limitations are far less stringent. Consequently, there’s a huge upside to going with traditional Medicare, and the downside is mitigated by the purchase of a Medigap plan, which covers the other 20 percent that Medicare doesn’t pay.

While this coverage is more expensive than most Medicare Advantage plans, nearly everybody in their old age would like to be able to choose their doctor and their hospitals, and everybody would want the security of knowing that they won’t be denied critical treatments. In 46 states, however, Medigap plans are allowed to engage in what’s called underwriting, or medical health screening, after seniors have already chosen a Medicare Advantage plan at age 65.

Only four states—New York, Connecticut, Maine, and Massachusetts—prevent Medigap underwriting for Medicare Advantage patients trying to switch back to traditional Medicare. The millions of Americans not living in those states are trapped in Medicare Advantage, because Medigap plans are legally able to deny them insurance coverage.

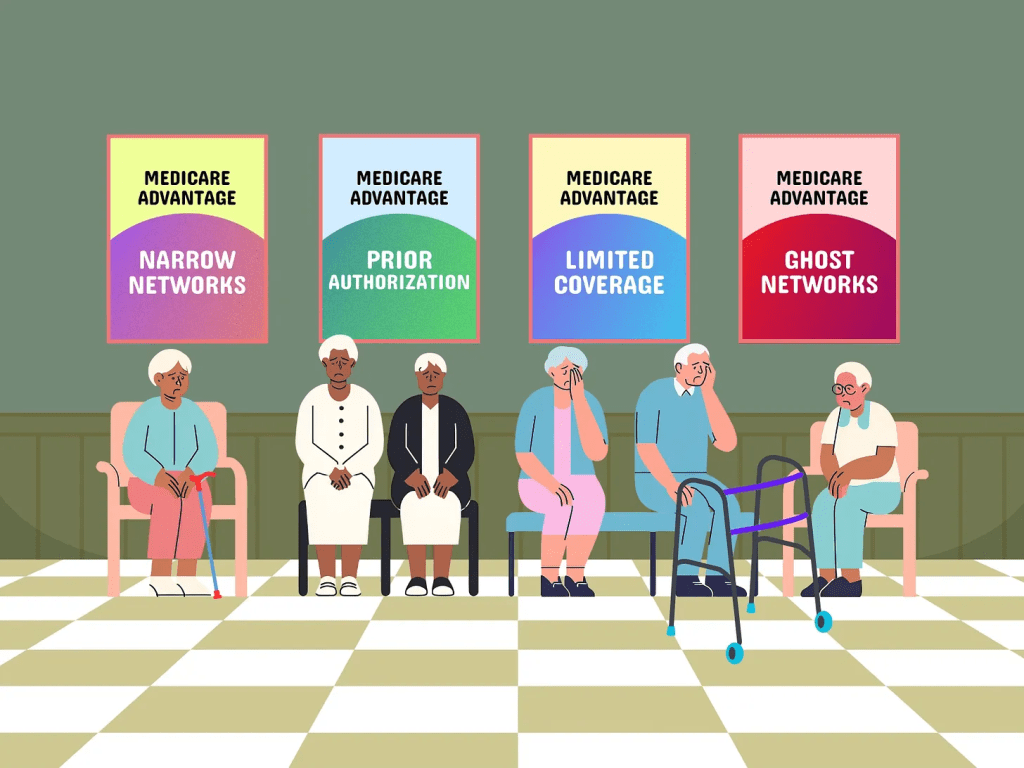

Medicare Advantage little resembles Medicare as it was traditionally intended, with tight networks and exorbitant costs that threaten to bankrupt the Medicare trust fund. (A recent estimate from Physicians for a National Health Program found that the program costs Medicare $140 billion annually.)

Jenn Coffey, a former EMT in New Hampshire who has been a vocal critic of her Medicare Advantage insurers’ attempts to deny her needed care, told the Prospect that she would jump back to traditional Medicare in a second. But because she became eligible prior to turning 65 due to a disability, she never had the option to pursue traditional Medicare with a Medigap plan. Instead, she pays premiums for a Medicare Advantage plan that nearly mirror what the cost of Medigap would be. But New Hampshire, like most other states, allows Medigap plans to reject her.

“I tried to find out if I could switch to traditional Medicare,” said Coffey. “When I talked to an insurance broker they said that I could. I made an appointment with an insurance agent, who then started looking at my pre-existing conditions, and they said, ‘We’re never going to get somebody to underwrite you.’”

Coffey was stunned by the agent’s words. “I honestly thought that we were completely done with pre-existing conditions” as a determinant for insurance coverage, she said. “Medigap plans are the only place where they are allowed to discriminate against us.”

Medicare Advantage now covers a majority of Medicare participants, thanks to extremely aggressive marketing and perks for healthier seniors like gym memberships.

In the 46 states that lack protections for people with pre-existing conditions, “lots of people don’t know that they may not be able to buy a Medigap plan if they go back to traditional Medicare from Medicare Advantage,” said Tricia Neuman, a senior vice president at KFF who has studied this particular issue.

Technically speaking, they can still go back to traditional Medicare if they don’t like their Medicare Advantage options, Neuman explained. But without access to a Medigap plan, they would be on the hook for 20 percent of their medical costs, which is unaffordable for most seniors.

Neuman told the Prospect about “cases where people have serious medical problems, and wanted to see a specialist,” but were blocked by their Medicare Advantage plan. Those same people had no ability to switch to traditional Medicare with a Medigap plan at precisely the time they need it the most, in nearly every state in the U.S.

“Medigap wasn’t a part of the ACA discussion on pre-existing conditions,” Neuman added. “A lot of people have no idea about this restriction on Medicare coverage, until they find themselves in a position that they want to go back and then it could be too late.”

Academic research shows that seniors often seek to return to traditional Medicare when they become sick.

The critical component that both Medigap and Medicare Advantage plans offer, which traditional Medicare does not, is out-of-pocket caps, said Cristina Boccuti, a director at the West Health Policy Center. “People who want to leave their Medicare Advantage plan, maybe because they are experiencing problems in their plan’s network, decide to disenroll and can’t obtain an out-of-pocket limit which they had previously had in Medicare Advantage,” Boccuti said.

That’s exactly the problem facing Rick Timmins, a retired veterinarian in Washington state. When Timmins was continually delayed care for melanoma, he explored getting out of his Medicare Advantage plan. “I wanted out of Medicare Advantage big-time,” said Timmins. But when he began to look at Medigap plans, he was told that he wouldn’t be guaranteed to get a plan, and that the insurance company could raise premiums based on a pre-existing condition.

“I doubt that I’ll be able to switch over to traditional Medicare, as I can’t afford high premiums,” Timmins said. “I’m still paying off some old medical debt, so it adds to my medical expenses.”

Medicare was founded in 1965 to end the crisis of medical care being denied to senior citizens in America. “No longer will older Americans be denied the healing miracle of modern medicine,” Lyndon Johnson said at the time. “No longer will illness crush and destroy the savings that they have so carefully put away over a lifetime so that they might enjoy dignity in their later years. No longer will young families see their own incomes, and their own hopes, eaten away simply because they are carrying out their deep moral obligations to their parents, and to their uncles, and their aunts.”

But slowly, private insurers were able to progressively expand their presence in Medicare, with a colossal advance made through George W. Bush’s Medicare prescription drug program in 2003. Now, Medicare Advantage covers a majority of Medicare participants, thanks to extremely aggressive marketing and perks for healthier seniors like gym memberships.

Numerous recent studies have shown Medicare Advantage plans to deny care while boosting the profits of private insurance companies. Defenders of Medicare Advantage argue that managed care—which practically speaking means insurance employees denying care to seniors—improves our health care system.

Denial-of-care issues,

combined with the aforementioned $140 billion drain on the trust fund, have attracted far more scrutiny of the program than in years past. Community organizations like People’s Action, along with other groups like Be A Hero, have stepped up their criticism of the program. The Biden administration proposed new rules this year to curb overbilling through the use of medical codes, but a furious multimillion-dollar lobbying campaign from the health insurance industry led to the rules being implemented gradually.

Still, members of Congress have become more emboldened to speak out against abuses in Medicare Advantage. A recent Senate Finance Committee hearing featured bipartisan complaints about denying access to care. And House Democrats have urged the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to crack down on increases in prior authorizations for certain medical procedures, as well as the use of artificial-intelligence programs to drive denials.

Megan Essaheb, People’s Action’s director of federal affairs, said that Medicare Advantage has become a drain on the federal trust fund. “These private companies are making tons of money,” Essaheb said. “The plans offer benefits on the front end without people understanding that they will not get the benefits of traditional Medicare, like being able to choose your doctor.”

Despite the growing scrutiny, the trapping of patients who want to get out of Medicare Advantage hasn’t gotten as much attention from either Congress or state legislatures that could end the practice.

Coffey, the retired EMT from New Hampshire, told the Prospect that she has paid $6,000 in out-of-pocket expenses this year under a Medicare Advantage program. “If I could go to Medigap, I would have better access to care, I wouldn’t be forced to give up Boston doctors,” she said.

“These insurance companies are allowed to reap as much profit as possible for as little service as they can get away with. They pocket all of our money and they don’t pay for anything, they sit there and deny and delay.”