The administration has already begun to implement some policies along these lines, according to current and former officials as well as experts, particularly with regard to testing.

The approach’s chief proponent is Scott Atlas, a neuroradiologist from Stanford’s conservative Hoover Institution, who joined the White House earlier this month as a pandemic adviser. He has advocated that the United States adopt the model Sweden has used to respond to the virus outbreak, according to these officials, which relies on lifting restrictions so the healthy can build up immunity to the disease rather than limiting social and business interactions to prevent the virus from spreading.

Sweden’s handling of the pandemic has been heavily criticized by public health officials and infectious-disease experts as reckless — the country has among the highest infection and death rates in the world. It also hasn’t escaped the deep economic problems resulting from the pandemic.

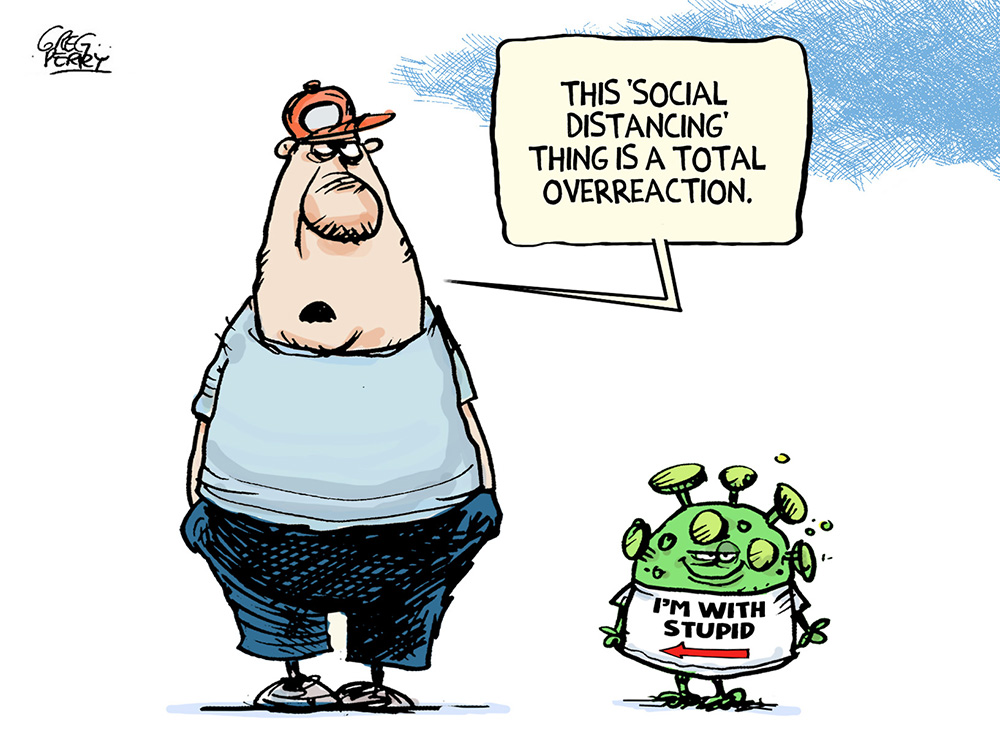

But Sweden’s approach has gained support among some conservatives who argue that social distancing restrictions are crushing the economy and infringing on people’s liberties.

That this approach is even being discussed inside the White House is drawing concern from experts inside and outside the government who note that a herd immunity strategy could lead to the country suffering hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of lost lives.

“The administration faces some pretty serious hurdles in making this argument. One is a lot of people will die, even if you can protect people in nursing homes,” said Paul Romer, a professor at New York University who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2018. “Once it’s out in the community, we’ve seen over and over again, it ends up spreading everywhere.”

Atlas, who does not have a background in infectious diseases or epidemiology, has expanded his influence inside the White House by advocating policies that appeal to Trump’s desire to move past the pandemic and get the economy going, distressing health officials on the White House coronavirus task force and throughout the administration who worry that their advice is being followed less and less.

Atlas declined several interview requests in recent days. After the publication of this story, he released a statement through the White House: “There is no policy of the President or this administration of achieving herd immunity. There never has been any such policy recommended to the President or to anyone else from me.”

White House communications director Alyssa Farah said there is no change in the White House’s approach toward combatting the pandemic.

“President Trump is fully focused on defeating the virus through therapeutics and ultimately a vaccine. There is no discussion about changing our strategy,” she said in a statement. “We have initiated an unprecedented effort under Operation Warp Speed to safely bring a vaccine to market in record time — ending this virus through medicine is our top focus.”

White House officials said Trump has asked questions about herd immunity but has not formally embraced the strategy. The president, however, has made public comments that advocate a similar approach.

“We are aggressively sheltering those at highest risk, especially the elderly, while allowing lower-risk Americans to safely return to work and to school, and we want to see so many of those great states be open,” he said during his address to the Republican National Convention Thursday night. “We want them to be open. They have to be open. They have to get back to work.”

Atlas has fashioned himself as the “anti-Dr. Fauci,” one senior administration official said, referring to Anthony S. Fauci, the nation’s top infectious-disease official, who has repeatedly been at odds with the president over his public comments about the threat posed by the virus. He has clashed with Fauci as well as Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, over the administration’s pandemic response.

Atlas has argued both internally and in public that an increased case count will move the nation more quickly to herd immunity and won’t lead to more deaths if the vulnerable are protected. But infectious-disease experts strongly dispute that, noting that more than 25,000 people younger than 65 have died of the virus in the United States. In addition, the United States has a higher number of vulnerable people of all ages because of high rates of heart and lung disease and obesity, and millions of vulnerable people live outside nursing homes — many in the same households with children, whom Atlas believes should return to school.

“When younger, healthier people get the disease, they don’t have a problem with the disease. I’m not sure why that’s so difficult for everyone to acknowledge,” Atlas said in an interview with Fox News’s Brian Kilmeade in July. “These people getting the infection is not really a problem and in fact, as we said months ago, when you isolate everyone, including all the healthy people, you’re prolonging the problem because you’re preventing population immunity. Low-risk groups getting the infection is not a problem.”

Atlas has said that lockdowns and social distancing restrictions during the pandemic have had a health cost as well, noting the problems associated with unemployment and people forgoing health care because they are afraid to visit a doctor.

“From personal communications with neurosurgery colleagues, about half of their patients have not appeared for treatment of disease which, left untreated, risks brain hemorrhage, paralysis or death,” he wrote in The Hill newspaper in May

The White House has left many of the day-to-day decisions regarding the pandemic to governors and local officials, many of whom have disregarded Trump’s advice, making it unclear how many states would embrace the Swedish model, or elements of it, if Trump begins to aggressively push for it to be adopted.

But two senior administration officials and one former official, as well as medical experts, noted that the administration is already taking steps to move the country in this direction.

The Department of Health and Human Services, for instance, invoked the Defense Production Act earlier this month to expedite the shipment of tests to nursing homes — but the administration has not significantly ramped up spending on testing elsewhere, despite persistent shortages. Trump and top White House aides, including Atlas, have also repeatedly pushed to reopen schools and lift lockdown orders, despite outbreaks in several schools that attempted to resume in-person classes.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also updated its testing guidance last week to say that those who are asymptomatic do not necessarily have to be tested. That prompted an outcry from medical groups, infectious-disease experts and local health officials, who said the change meant that asymptomatic people who had contact with an infected person would not be tested. The CDC estimates that about 40 percent of people infected with covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, are asymptomatic, and experts said much of the summer surge in infections was due to asymptomatic spread among young, healthy people.

Trump has previously floated “going herd” before being convinced by Fauci and others that it was not a good idea, according to one official.

The discussions come as at least 5.9 million infections have been reported and at least 179,000 have died from the virus this year and as public opinion polls show that Trump’s biggest liability with voters in his contest against Democratic nominee Joe Biden is his handling of the pandemic. The United States leads the world in coronavirus cases and deaths, with far more casualties and infections than any other developed nation.

The nations that have most successfully managed the coronavirus outbreak imposed stringent lockdown measures that a vast majority of the country abided by, quickly ramped up testing and contact tracing, and imposed mask mandates.

Atlas meets with Trump almost every day, far more than any other health official, and inside the White House is viewed as aligned with the president and White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows on how to handle the outbreak, according to three senior administration officials.

In meetings, Atlas has argued that metropolitan areas such as New York, Chicago and New Orleans have already reached herd immunity, according to two senior administration officials. But Birx and Fauci have disputed that, arguing that even cities that peaked to potential herd immunity levels experience similar levels of infection if they reopen too quickly, the officials said.

Trump asked Birx in a meeting last month whether New York and New Jersey had reached herd immunity, according to a senior administration official. Birx told the president there was not enough data to support that conclusion.

Atlas has supporters who argue that his presence in the White House is a good thing and that he brings a new perspective.

“Epidemiology is not the only discipline that matters for public policy here. That is a fundamentally wrong way to think about this whole situation,” said Avik Roy, president of the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, a think tank that researches market-based solutions to help low-income Americans. “You have to think about what are the costs of lockdowns, what are the trade-offs, and those are fundamentally subjective judgments policymakers have to make.”

It remains unclear how large a percentage of the population must become infected to achieve “herd immunity,” which is when enough people become immune to a disease that it slows its spread, even among those who have not been infected. That can occur either through mass vaccination efforts, or when enough people in the population become infected with coronavirus and develop antibodies that protect them against future infection.

Estimates have ranged from 20 percent to 70 percent for how much of a population would need to be infected. Soumya Swaminathan, the World Health Organization’s chief scientist, said given the transmissibility of the novel coronavirus, it is likely that about 65 to 70 percent of the population would need to become infected for there to be herd immunity.

With a population of 328 million in the United States, it may require 2.13 million deaths to reach a 65 percent threshold of herd immunity, assuming the virus has a 1 percent fatality rate, according to an analysis by The Washington Post.

It also remains unclear whether people who recover from covid-19 have long-term immunity to the virus or can become reinfected, and scientists are still learning who is vulnerable to the disease. From a practical standpoint, it is also nearly impossible to sufficiently isolate people at most risk of dying due to the virus from the younger, healthier population, according to public health experts.

Atlas has argued that the country should only be testing people with symptoms, despite the fact that asymptomatic carriers spread the virus. He has also repeatedly pushed to reopen schools and advocated for college sports to resume. Atlas has said, without evidence, that children do not spread the virus and do not have any real risk from covid-19, arguing that more children die of influenza — an argument he has made in television and radio interviews.

Atlas’s appointment comes after Trump earlier this summer encouraged his White House advisers to find a new doctor who would argue an alternative point of view from Birx and Fauci, whom the president has grown increasingly annoyed with for public comments that he believes contradict his own assertions that the threat of the virus is receding. Advisers sought a doctor with Ivy League or top university credentials who could make the case on television that the virus is a receding threat.

Atlas caught Trump’s attention with a spate of Fox News appearances in recent months, and the president has found a more simpatico figure in the Stanford doctor for his push to reopen the country so he can focus on his reelection. Atlas now often sits in the briefing room with Trump during his coronavirus news conferences, even as other doctors do not. He has given the president somewhat of a medical imprimatur for his statements and regularly helps draft the administration’s coronavirus talking points from his West Wing office as well as the slides that Trump often relies on for his argument of a diminishing threat.

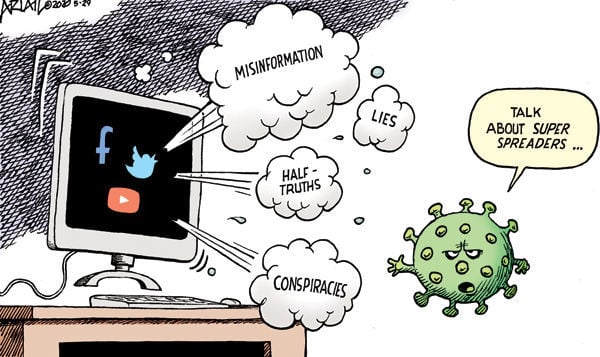

Atlas has also said he is unsure “scientifically” whether masks make sense, despite broad consensus among scientists that they are effective. He has selectively presented research and findings that support his argument for herd immunity and his other ideas, two senior administration officials said.

Fauci and Birx have both said the virus is a threat in every part of the country. They have also put forward policy recommendations that the president views as too draconian, including mask mandates and partial lockdowns in areas experiencing surges of the virus.

Birx has been at odds with Atlas on several occasions, with one disagreement growing so heated at a coronavirus meeting earlier this month that other administration officials grew uncomfortable, according to a senior administration official.

One of the main points of tension between the two is over school reopenings. Atlas has pushed to reopen schools and Birx is more cautious.

“This is really unfortunate to have this fellow Scott Atlas, who was basically recruited to crowd out Tony Fauci and the voice of reason,” said Eric Topol, a cardiologist and head of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego. “Not only do we not embrace the science, but we repudiate the science by our president, and that has extended by bringing in another unreliable misinformation vector.”