Category Archives: Stakeholder

Healthcare’s Wicked Problems

One of the great things about my job is getting the opportunity to talk with healthcare CEOs around the country on a regular basis.

Lately, every CEO I talk with tells me how hard it is to run a healthcare organization in 2023.

These are people with long experience, people who over time have pushed the right buttons and pulled the right levers to make their organizations successful and to give their communities the care they need.

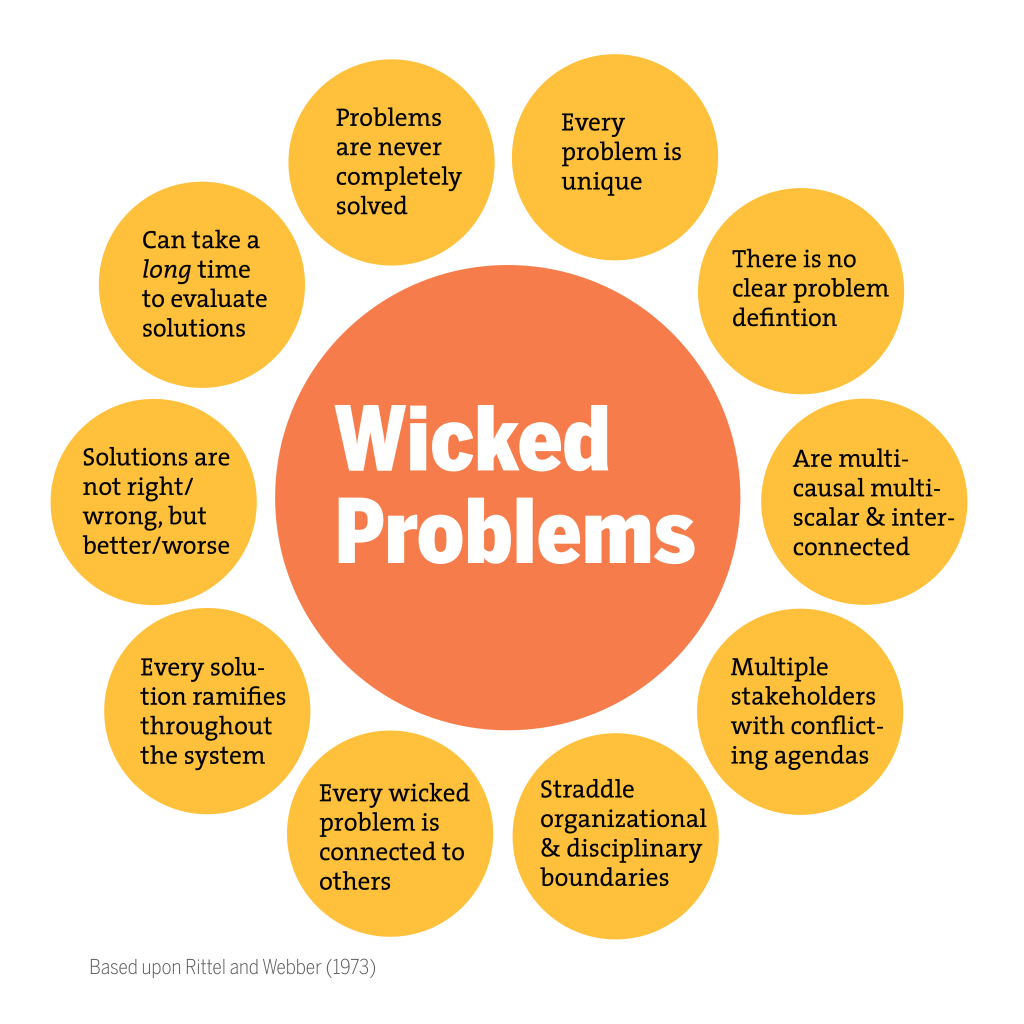

Hearing these recent comments from CEOs takes us back to the concept of “wicked problems,” which we’ve referred to in the past, and suggests that the current hospital operating environment is overwhelmed by wicked problems.

As a reminder, the wicked problem concept was developed in 1973 by social scientists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber.

Unlike math problems, wicked problems have no single, correct solution. In fact, a solution that improves one aspect of a wicked problem usually makes another aspect of the problem worse.

Poverty is a common example of a wicked problem.

According to Rittel and Webber, all wicked problems have these five characteristics:

- They are hard to define.

- It’s hard to know when they are solved.

- Potential solutions are not right or wrong, only better or worse.

- There is no end to the number of solutions or approaches to a wicked problem.

- There is no way to test the solution to a wicked problem—once implemented, solutions are not easily reversable, and those solutions affect many people in profound ways.

Healthcare is one of our nation’s critical wicked problems, and the broad and persistent effects of COVID have made that problem worse.

Like all wicked problems, the wicked problem of healthcare can be defined in many different ways and from many different perspectives.

If we were to frame the wicked problem of healthcare just in the context of hospitals and health systems coming off of their worst financial year in memory, it could look something like this:

Hospitals and health systems need to make a margin in order to carry out their “duty of care”—that is, their responsibility to improve health for communities, which increasingly include public health undertakings.

However, in 2022, more than half of hospitals in America had negative margins due largely to macroeconomic factors related to labor, inflation, utilization, and insufficient revenue growth.

The actions then needed to improve financial performance likely involve reducing labor costs and eliminating unprofitable services.

But these solutions in the hospital world are seen as another wicked problem, and actions taken to improve financial and clinical operations are often cautiously approached in order to protect the organization’s duty of care.

As you can see, the very actions to solve the wicked problem of provider healthcare may likely make aspects of the strategic problem worse.

Everyone reading this blog is dedicated to solving these and other wicked problems related to health and healthcare and the provision of sufficient care to the American community.

Solutions to healthcare’s wicked problems are never clear, and those solutions are not easily tested and eventually can affect many.

And in the wicked problem lexicon, once uncertain solutions have been implemented they are very hard to undo.

And healthcare’s many and varied dissatisfied stakeholders demand rapid solutions and then complain loudly when those solutions fall short, as any one solution inevitably will when the problem is as wicked as the current healthcare environment.

This is the new role of healthcare leaders: solvers of wicked problems.

Cartoon – Humble Leadership

INSIGHT: Health-Care M&A Post-Pandemic—Opportunities, Not Opportunism

The Covid-19 pandemic has devastated the health-care industry. In addition to the tragedies that the pandemic has brought, health systems have universally experienced severe and rapid deterioration of their bottom lines due to plummeting patient volumes, pausing of high margin elective surgical procedures, and increased expenses.

By some estimates, health system losses will be around $200 billion by the end of June and revenues have dropped by around 50 percent. As a result of the financial uncertainty caused by the pandemic, many hospital and health systems terminated or delayed potential transactions as they focused on managing the crisis and protecting their workforces and communities.

But this may just be the calm before a big M&A storm.

Rise in M&A Activity

Through our work as legal and communications counselors, we have seen preliminary M&A activity rise in recent weeks, with providers exploring and negotiating transactions, including several that have not yet been publicly announced.

Some systems are looking to capitalize on the time between the end of the first wave of Covid-19 and a potential resurgence in the fall to get letters of intent finalized and announced. This coming M&A activity presents legal and communications challenges when the national spotlight is firmly on health systems.

Providers are starting to resurrect deals that were paused during the initial period of the Covid-19 crisis, including Community Health System’s sale of Abilene Regional Medical Center and Brownwood Regional Medical Center to Hendrick Health System.

Some systems are seeking new strategic partners, such as Lake Health in Ohio, and New Hanover Regional Medical Center in North Carolina, which resumed its recent RFP response process after a pause.

Still others are looking for new opportunities consistent with pre-Covid growth strategies, as adjusted for pandemic-related developments and challenges.

More Consolidation

Larger and more financially robust health systems are expected to weather the crisis, whereas smaller systems and hospitals with less cash and tighter operating margins, including rural and critical access hospitals, may be facing insolvency, closure, and bankruptcy. This creates a scenario where one party is financially distressed as a result of the pandemic and needs to partner with or join another system to survive. These circumstances will likely fuel increased consolidation in the health-care industry.

For a struggling provider, joining a larger system can offer much-needed financial commitments, access to capital, disciplined management structure, economies of scale for purchasing and improved IT infrastructure, among many other strategic benefits. A well-positioned system, even if financially weakened due to pandemic challenges, will be able to negotiate favorable deal terms if it has significant strategic value to its prospective partner.

Communications Strategy is Important

As providers explore and execute partnerships, they must implement a stakeholder and communications strategy that focuses on benefits for each side given the new financial reality. Doing so will minimize criticism of opportunism by the acquiring system—and best position a definitive agreement and successful deal.

An effective communications strategy will emphasize how the proposed transaction will maintain or improve quality or affordability, ensure access to care for communities and address financial challenges faced by health systems as a result of the pandemic.

Health systems should articulate how their M&A activity will stabilize affected health systems, allow them to manage the Covid-19 crisis and future pandemics, and continue to meet the overall care needs of the community. It can also highlight how these partnerships will facilitate continued care in a market, which otherwise might lose a valuable health-care resource, as well as the positive economic benefits the transaction will bring for local communities.

Communications that support the vision, rationale and benefits of a deal will also need to be relevant to the regulatory bodies whose approval may be required.

Public perception and support of health-care providers have been extremely positive during the pandemic to date, as evidenced by homemade banners, balcony tributes, and praise on social media. Health systems and their staffs have borne personal risk and financial pain by focusing on patients and public health at the expense of all else. This goodwill can be valuable as health systems seek stakeholder and community support for their transactions.

That goodwill can also quickly be forgotten.

As health systems race to the altar to beat out competitors for M&A targets and other strategic relationships, it is critical that they are thoughtful in structuring their deals and justifying the activity.

For example, acquisitions and partnerships involving substantial outlays of capital and lucrative executive compensation or severance packages will be viewed negatively if undertaken by a system that instituted large compensation reductions across the system or even furloughed or laid off employees during the pandemic.

As the dust begins to settle from the first wave of Covid-19, it is clear that there will be drastic changes to how health systems do business. The pandemic will also create financial winners and losers. Hospitals and health systems must think proactively about a strategy for growth as opportunities with willing transaction partners arise.

But being proactive must be balanced against appearing to be opportunistic or taking advantage of the worst health crisis in our lifetimes. To maintain their goodwill and reputations, health systems should continue to do deals for the right reasons and for the benefit of their communities.