The Medicare trustees’ new projection for insolvency is five years later than previous forecasts, but budget hawks warned action is still needed to shore up the insurance program’s finances.

Dive Brief:

- A key trust fund underpinning the massive Medicare program has a new insolvency date: 2036, according to a new report from the Medicare trustees.

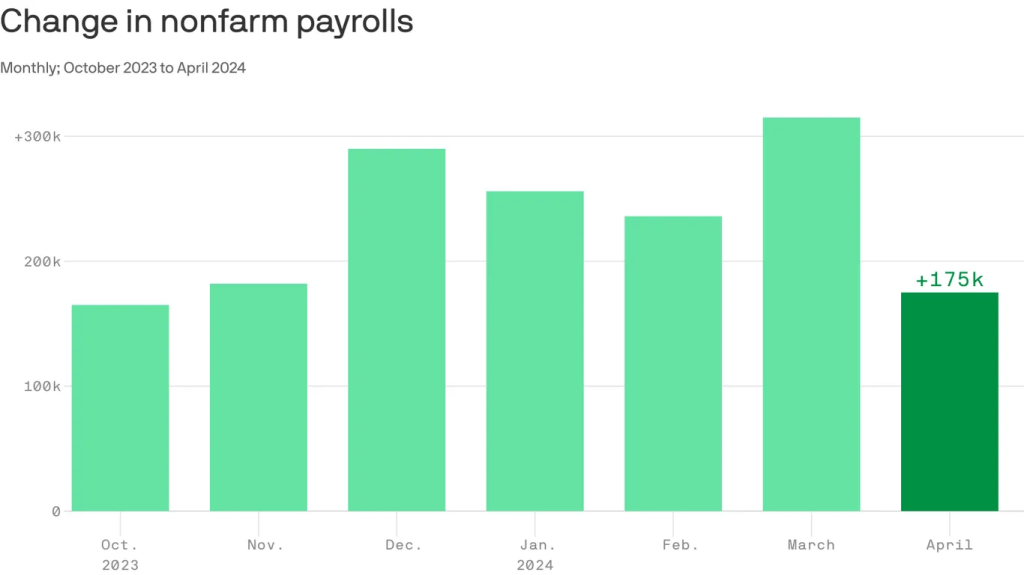

- That’s five years later than the go-broke date in last year’s report, thanks to more workers being paid higher wages causing more revenue to flow into the trust fund’s coffers, along with lower spending on pricey hospital and home health services.

- Still, looming insolvency absent action in Washington remains a serious source of concern for the longevity of Medicare, which covers almost 67 million senior and disabled Americans, according to budget hawks.

Dive Insight:

Dire predictions in the annual Medicare trustees report have varied in the past few years. In 2020, in the early throes of COVID-19, the board predicted the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund fund would run out by 2026. That deadline was pushed back to 2028 and then 2031 in subsequent years’ reports, amid a broader economic rebound and more care shifting to cheaper outpatient settings.

Now, the trustees — a group comprised of the Treasury, Labor and HHS secretaries, along with the Social Security commissioner — are forecasting an additional five years of breathing room for Medicare solvency.

Along with the healthier economy, that’s in part due to the Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022, which restrains price growth and allows Medicare to negotiate drug prices for certain Part B and Part D drugs, and should lower government spending in the program overall, according to the report.

The Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which pays hospitals and providers of post-acute services, and also covers some of the cost of private Medicare Advantage plans, is mostly funded by payroll taxes, along with income from premiums.

The HI fund is separate from another trust fund that covers benefits for Medicare Parts B and D, including outpatient services and physician-administered drugs. That Supplemental Medical Insurance trust fund is largely funded by premiums and general revenue that resets each year and doesn’t face the same solvency concerns.

In 2023, HI income exceeded spending by $12.2 billion. Surpluses should continue through 2029, followed by deficits until the fund runs out entirely in 2036, according to the report.

At that point, the government won’t be able to pay full benefits for inpatient hospital visits, nursing home stays and home healthcare.

Spending is projected to grow substantially in Medicare largely due to demographic changes.

The number of Americans at the qualification age for Medicare is projected to reach 95 million by 2060, rising from 16% of the total population in 2018 to 23% at that time, according to the Census Bureau. As a result, beneficiaries in the program will swell as the number of workers paying into the trust fund shrinks.

The trustees forecast Medicare’s costs under current law will rise steadily from their current level of 3.8% of the gross domestic product, to 5.8% in 2048 and 6.2% by 2098.

To date, lawmakers have not allowed the Medicare trust fund to become depleted. But amid increasingly dire warnings from trustees and watchdogs urging the need to align spending with revenue, Congress has delayed taking action to improve Medicare’s finances, following bipartisan efforts to lower spending in the early 2010s.

The fund hasn’t met the trustees’ test for short-range financial adequacy since 2003, and has triggered funding warnings since 2018.

“The absurd part is that we’ve known insolvency was looming for quite some time. We’re driving straight into this mess despite all the warning bells and alarms that the Trustees and others have been ringing for decades now,” Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said in a statement on the report.

Along with concerns about Medicare access and quality for seniors, physicians will also be heavily affected by Medicare insolvency, according to the report. Physician groups, which perennially slam Medicare for low payment rates as it is, used the report to lobby for spending reform to align reimbursement with the cost of practicing medicine.

The American Medical Association argued the report highlights the need for policy changes, such as linking the annual payment update for doctors to the Medicare Economic Index, a measure of practice cost inflation — a suggestion also supported by influential congressional advisory group MedPAC.

“It would be political malpractice for Congress to sit on its hands and not respond to this report,” AMA President Jesse Ehrenfeld said in a statement.

Federal entitlement programs like Medicare remain on shaky ground because lawmakers are loath to take steps to increase revenue (i.e. raise taxes) or lower spending (i.e. raise the age of eligibility), measures deeply unpopular with voters.

Last year, President Joe Biden pitched a plan to keep Medicare’s hospital trust fund solvent beyond 2050 without cutting benefits. The plan would further reduce what Medicare pays for prescription drugs and raise taxes on Americans earning over $400,000.

There has been no movement in Congress on the proposal. Yet in a statement Monday, Biden took credit for strengthening Medicare, while his campaign in an email reupped comments from Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump that if elected he would consider cutting Medicare and other entitlement programs. Trump, who later walked back the comments, has not proposed a plan to address Medicare’s shortfall.