Americans Move Toward Medicare for All Amid Current Health Care Debate

As lawmakers debate ACA subsidy extensions and HSAs tied to banks and insurers, the public’s appetite for a health care overhaul is stronger than at any time since the 2020 Democratic primaries.

Washington is running out of hours to address the health care crisis of their own making. There are just 23 days before the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) enhanced subsidies expire and congressional leaders are still trading barbs and floating half-baked ideas as millions of Americans brace for punishing premium spikes.

Meanwhile, the public has grown frustrated with both congressional dysfunction, and private health insurance companies that continue to raise premiums and out-of-pocket costs at a dizzying pace. According to new KFF data, 6 in 10 ACA enrollees already struggle to afford deductibles and co-pays, and most say they couldn’t absorb even a $300 annual increase without financial pain.

And even as Congress flails, Americans are coalescing around a solution party leaders rarely mention: Medicare for All.

A dramatic rebound in popularity

After Senator Bernie Sanders bowed out of the presidential race in April 2020, Medicare for All faded to the background following political infighting, industry fearmongering and the lack of a national champion. But nearly six years later, the proposed policy solution has re-emerged as a top choice among frustrated voters.

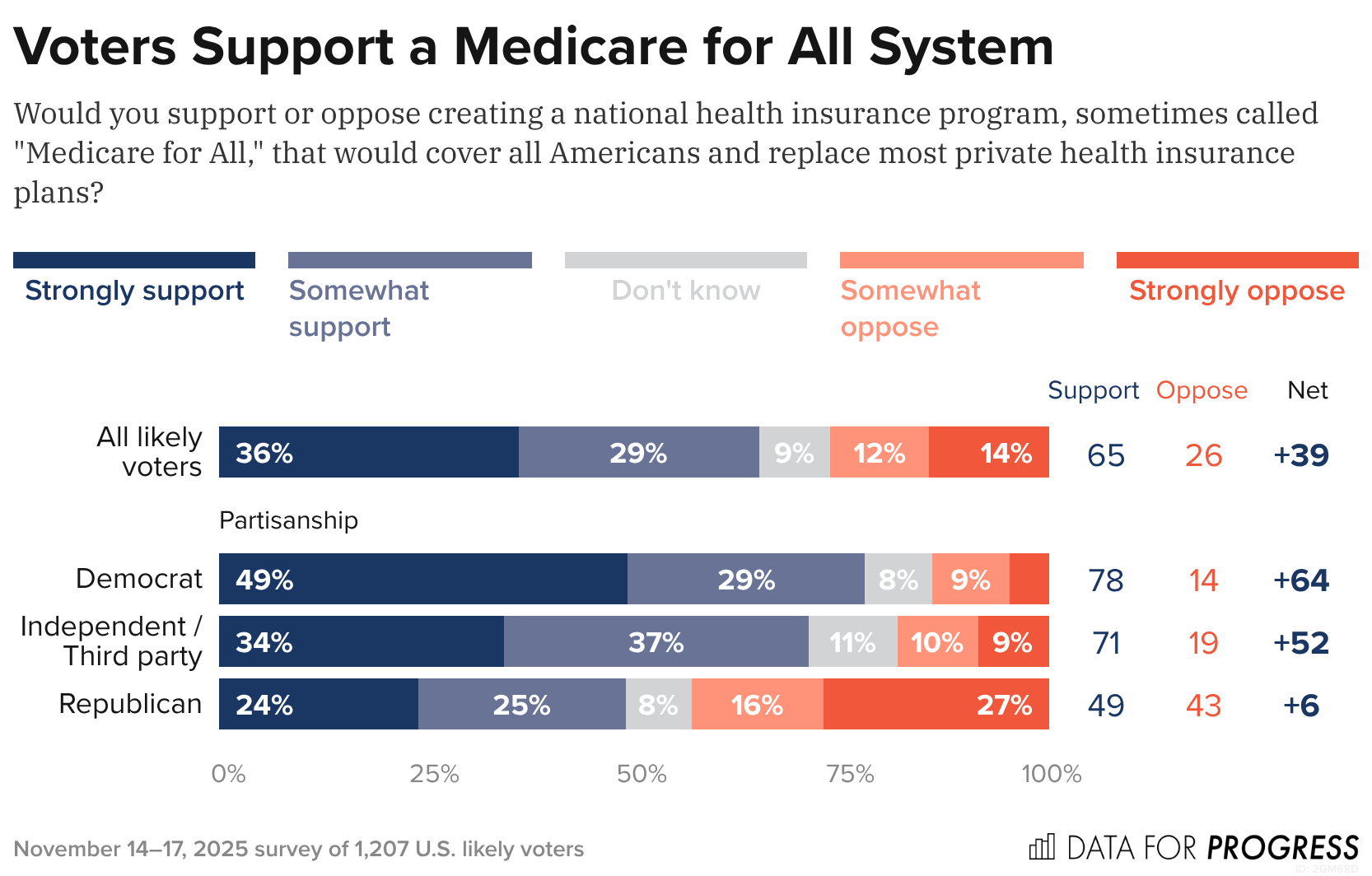

A new Data for Progress poll found that 65% of likely voters (including 71% of independents and nearly half of Republicans) support creating a national health insurance program that would replace most private plans. What’s notable is that the poll shows that support barely budges – holding at 63% – even when voters are told Medicare for All would eliminate private insurance and replace premiums with taxes, a dramatic shift from years past when just 13% supported such a plan under those conditions.

These new polls show that Americans are not simply dissatisfied with the looming subsidy crisis. But instead, as I wrote last month, they’re losing faith in the current system that allows Big Insurance to collect record profits at the expense of Americans’ health and bank accounts.

The KFF poll shows that ACA enrollees lack confidence that President Trump or congressional Republicans will handle the crisis, with almost half of ACA enrollees saying a $1,000 cost spike would “majorly impact” their vote in 2026. More than half of ACA enrollees are in Republican congressional districts, which explains why Republicans representing swing districts are desperately trying to persuade their Republican colleagues — so far without success — to extend the subsidies.

Of course, Medicare for All still faces steep odds in Congress. Industry opposition remains powerful, Democrats are divided and Republicans are openly hostile. But the polling shift is significant and suggests the political terrain is changing faster than Washington is acknowledging — and that voters, squeezed by soaring premiums and dwindling subsidies, are being nudged toward policies previously attacked as too ambitious to pass.

And against this backdrop, Medicare for All’s revival feels less like a left-wing wet dream and more like a window into the public’s thinning patience. Americans are looking past the Affordable Care Act’s limits and past Big Insurance’s promises – and towards a solution that decouples Americans health from profit-hungry, Wall Street-driven corporate monsters. While Washington has met this moment with inaction, Americans seem ready to act.

America’s Three Economies: Vibes Sinking, Data Treading Water, Elites Sailing Away

As we approach the end of 2025, it’s a good time to take stock of the US economy. There’s justifiable concern that this year has entrenched a K-shaped economy, where the have-mores leave the haves and have-nots behind. But there are more than two stories going on right now.

First, the vibes are bad (just ask anyone coming out of a grocery store). Second, the real economy—prices, jobs, and consumer and business spending, among other factors—is worse than it was a year ago, but holding up OK (4.4 percent unemployment, GDP growth over 2 percent, and inflation around 3 percent is hardly the stuff of recession). Third, a small number of people and companies are doing extremely well.

Depending on where you stand, you’re hearing very different things about the economy, but a pretty consistent theme is an administration that has not delivered on promises made to voters—while delivering to the president’s family and friends.

Under the Hood, the Story Gets More Complicated

It’s been a predictably rough year for the US economy. Tariffs have raised goods prices and hit manufacturing jobs, immigration crackdowns have crippled the labor force, and reversing energy policies dramatically has unwound an energy investment boom. As a result, the job market is softer, prices are still high, and inflation is up and apparently rising based on the data flow that has (finally) started to trickle back in.

That said, if the data are weaker, the economic mood of the country is, in a word, awful. Consumer sentiment in October was only exceeded by lows from the worst of the early 1980s recession, the peak of the 2022 inflation, and the months following the “Liberation Day” tariff announcement this year. Since January, consumer sentiment has plunged, giving up essentially all gains from a steady rise after the inflation peak of 2022.

That pessimism isn’t purely emotional—it reflects months of higher grocery and utility bills. In fact, across both the major household expectations surveys, families expect inflation to keep going up next year—which most economists expect as well. And roughly twice as many consumers surveyed by the Conference Board expect the jobs picture to be weaker rather than stronger in the next six months.

This view is both pessimistic and realistic given the data we’ve seen so far this year. It’s unmistakably true that the labor market and the inflation picture are weaker than last fall. What’s worrying to the wonkier economy watchers, however, is that the pressures on both inflation and unemployment are in the wrong direction. There are real risks that both inflation and the jobs picture could get worse, but (short of policy reversals) few predictable shocks are likely to make either improve in the near term.

Job growth has stayed positive but slowed dramatically, from an average 167,000 jobs a month in January to just 109,000 in September (and will likely be revised down further with annual revisions early next year). Over 87 percent of all jobs added this year are in health care and social assistance (a given in an aging country), while the rest of the economy has added just 71,000 jobs all year. And there’s little sign that tariffs are about to bring down prices, nor are there signs that the demand side of the economy is about to pick up.

It’s Not Great, but There’s Plenty of Time to Panic Later

The closer you are to the data, the less pessimistic you probably are right now. But, as we can see in recent Fed meeting minutes, the debate is largely between two camps: The first is those who think the labor market is middling and the risks of rising inflation are serious. The second is those who think the risks of rising inflation are less worrisome than the chances the labor market deteriorates further.

It’s clearly too soon to panic about a recession, and the best labor market data we have say things are holding up well by historical standards—September’s 4.4 percent unemployment is better than about 80 percent of months since 2000—it’s just that there’s little to suggest things are about to improve significantly.

That said, the economy continues to chug along on the strength of spending by resilient, yet quite frustrated, consumers. The final reading on second quarter GDP shows US consumer spending keeping the economy going, even as savings deplete.

Early holiday spending numbers look strong, so it seems like US consumers are going to muddle through tariffs. The distribution of consumer spending remains pretty narrow—high earners are doing much more of the broad-based spending in the economy

However, if you get your news from stock markets, or even from retirement statements, the world is different entirely, and much more optimistic—at least from a high level. After a massive swoon in April, the US stock market has had a great year, powered by tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy and an AI investment boom that looks bubble-like to some inside it.

Yet, like in the real economy, the more you dig into the data the farther from the extremes your views can go. Job and corporate earnings growth are concentrated in increasingly narrow slices of the economy. Corporate earnings are notoriously concentrated at this point, with the top 1.4 percent of S&P 500 companies accounting for almost all of stock market gains this year—just seven companies are now one-third of the value of S&P 500.

How Do We Square These Takes?

Overall, the data are on a more even keel than either the awful vibes most Americans are feeling from an affordability crisis or the anxiously warm vibes of investors. We’re not living through the economic boom tech investors see everywhere, nor the near-term dystopia consumers are feeling. The economy is weaker than last year and likely to continue to soften a bit more over the first part of next year, but the good news is at least for now things are not as bad in the data as in the headlines. The bad news is . . . that’s the good news.

Why Main Street’s pain matters

The economic fortunes of mom-and-pop businesses are diverging from those of their larger counterparts — a pre-existing gap that now appears to be getting bigger, faster.

Why it matters:

The evidence is in the private-sector labor market, that in recent months, has been propped up by large companies as smaller firms — typically responsible for 40% of U.S. employment — shed workers.

The big picture:

Larger businesses have been able to adapt to a tough economic backdrop — historic tariffs, high interest rates and a more cautious consumer — in ways far more challenging for small companies with fewer resources.

- “It’s evident that medium and large firms are better positioned to weather what’s going on,” said ADP chief economist Nela Richardson.

- “They can set prices, they can change suppliers. They can hire contractors instead of permanent employees in a more sophisticated way. They can hire globally, not just in their local region. They have more tools in the toolbox,” Richardson said.

By the numbers:

The hiring gap between small and big businesses is getting worse, a fresh sign that small business firings are holding down jobs growth across the economy.

- As we mentioned yesterday, the private sector shed 32,000 jobs in November, according to payroll processor ADP. Small firms — those with fewer than 50 employees — accounted for all of the losses.

- Those businesses reported a net loss of 120,000 jobs, the most small businesses have cut since the pandemic’s onset. Larger businesses grew, but not enough to offset the cuts elsewhere.

“Small business hiring really started to slow in April and I attribute some of this to tariffs and the higher cost of doing business that small companies are much less able to absorb,” Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer at One Point BFG Wealth Partners, wrote in a note.

- “The natural reaction is to cut costs elsewhere and we know that labor is their biggest cost,” Boockvar added.

The intrigue:

Bloomberg recently reported that there are more small businesses filing for bankruptcy under a special federal program this year than at any point in the program’s six-year history.

- Subchapter V filings, which allow firms to shed debt faster and cheaper, are up 8% from last year, according to data from Epiq Bankruptcy Analytics.

- Chapter 11 filings — a process used by larger businesses — are up roughly 1% over the same time frame.

Threat level:

Main Street is bearing the brunt of an economic slowdown in ways that might make it even harder for small shops to compete with larger companies.

- One bright spot: Despite that pain, applications to start new businesses — ones likely to employ other people — remain notably higher than in pre-pandemic times, according to the latest data available from the Census Bureau.

What to watch:

The Trump administration shrugged off the ADP data that indicated a hiring bust. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick told CNBC that the cuts were due to factors unrelated to tariffs, like immigration crackdowns.

- That hints at a debate among monetary policymakers, who are trying to gauge how much weak jobs growth is a byproduct of fewer available workers.

- But ADP had earlier told reporters that small businesses generally had less demand for workers — not that staff weren’t available for hire.

The Slow Death of Epic Systems

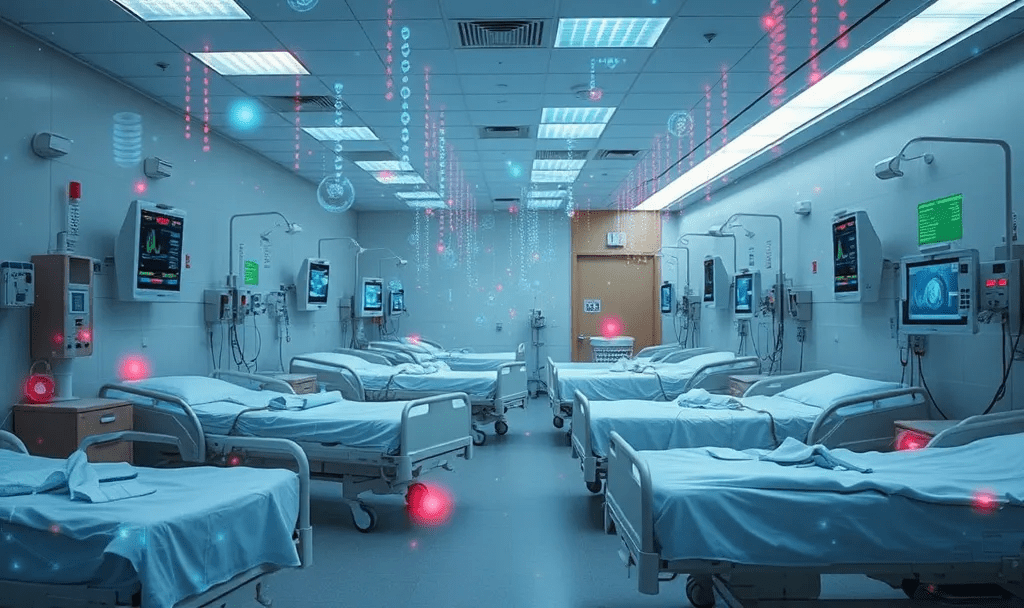

The software monopoly that powers American hospitals wasn’t built for the data, speed, or intelligence the future of medicine demands.

Epic Systems is an American privately held healthcare software company, founded by Judy Faulkner in 1979, and has grown into the largest electronic health record (EHR) vendor by market share, covering over half of all hospital patients in the U.S.

Epic dominates American healthcare today. But so did Kodak in photography and GE in industry. Its software runs the country’s hospitals, determines the workflows clinicians, nurses and clinical support staff use, and shapes what data gets captured (or more often, what gets lost). It also serves as the front door for healthcare data for the patients it serves. Dominance has never guaranteed a future. Epic’s position reflects the architecture of the past, not the one emerging now.

More importantly, the sheer volume of activity occurring in these hospitals means they are collectively running thousands of experiments, mini clinical trials, and critical observations daily. The stakes are enormous: billions of dollars in drug discovery, the efficiency of clinical trials (currently plagued by poor recruitment and high costs), and the potential for better, personalized care. The data generated in these environments is the single most valuable, untapped resource in all of medicine.

However, this monumental source of value is being throttled by outdated infrastructure, and it shows. It’s hard to imagine a world where AI is used to its full potential in healthcare while Epic is still running the show. The ideas are oppositional at their core.

The Massive Data Problem

Technology is accelerating faster than any legacy system can keep up with. AI is reshaping every major industry, and healthcare will be forced to catch up. However, this essential transformation is structurally incompatible with the dominant system of record.

To put it bluntly: Epic has a data problem. A massive data problem. Not just imperfect data — structurally flawed data. What Epic captures is fragmented, delayed, and riddled with inconsistencies. Diagnoses become billing codes that distort reality. Interventions like intubations, pressor starts, and ventilator changes appear hours late, if at all. Outcomes are incomplete or missing. What remains isn’t a clinical record in any meaningful sense but a billing ledger dressed up as documentation. No model can learn reliably from that.

But the deeper problem is the data Epic never sees. Some of the most valuable information in modern medicine: continuous monitoring streams, ventilator logs, infusion pump data… never enters the EHR in a structured or analyzable form. In many cases, it isn’t captured at all.

I recently brought Roon (a well-known engineer at OpenAI) and Richard Hanania (a public intellectual/cultural critic)—both advisors in my new venture, in full disclosure—to one of the largest academic medical centers in the country. Both watched torrents of millisecond-scale data spill off monitors. Streams that could reveal what’s happening in the brain, heart, and vasculature. Valuable data… all vanished instantly. None of it logged. None of it stored. None of it correlated with outcomes. Roon captured this shock in a viral post on X/Twitter, essentially describing how hospitals are filled with catastrophic events like sudden cardiac death, yet we save none of the time-series data that could teach us how to prevent the next one. His shock distilled what people in technology grasp immediately and what healthcare has normalized: industries where human life isn’t exactly top of mind record everything; hospitals, where the stakes are life and death, learn almost nothing from themselves.

In Silicon Valley, losing data like this is unthinkable. In healthcare, it barely registers.

Epic was never built to ingest or learn from this scale of data. It was built to satisfy billing requirements, regulatory checklists, and documentation workflows. That is the beginning and end of its architecture. It is not a learning system, much less an AI system. It is not even a modern data system. And that is the root of Epic’s downfall.

The Cultural and Financial Moat

Epic is famous for its internal commandments — principles Judy Faulkner wrote decades ago:

- Do not acquire.

- Do not be acquired.

- Do not raise outside capital.

(If you haven’t heard it, the latest Acquired podcast episode on Epic is essential listening)

But the same rules that built its empire now limit what it can become. What was once a strategic strength is now its ceiling.

The next era of healthcare software demands investments that were unnecessary when the EHR was the center of gravity. Building AI-native infrastructure: real-time data pipelines, device integrations, large-scale compute, continuous model training, semantic normalization — requires not millions but tens of billions of dollars. Most companies facing that kind of leap can raise capital, acquire talent, or merge with partners. Epic has ruled all of those options out.

Epic’s formidable market share is anchored by a massive customer sunk cost. With implementation fees often exceeding a billion dollars for large systems, the financial and political inertia makes replacing the EHR functionally unthinkable. However, this commitment only forces customers to defend an obsolete data architecture. By preventing them from adopting novel solutions, this inertia doesn’t protect Epic’s long-term viability, it simply guarantees a widening technical gap between the EHR and the transformative potential of AI.

A company optimized for slow, controlled expansion cannot transform itself into an AI-scale enterprise without violating the principles that define it. The culture that kept Epic dominant is the culture that prevents it from catching the next wave. Epic will continue to excel at documentation, billing, and compliance — but those strengths are anchored in the past. The future belongs to systems that learn, and Epic was never designed to learn.

The Shift to Middleware

Meanwhile, the broader economy is being held up by AI. The world’s largest tech companies are pouring staggering sums into compute, data centers, and model training. And all that compute needs rich, complex, high-value data to train on.

Healthcare is the only remaining frontier of that scale.

No other industry generates so much information while analyzing so little of it. No other sector represents nearly 20% of U.S. GDP yet still runs on fragmented workflows and manual processes. And the incentives here are unmatched: improving patient outcomes, reducing costs, eliminating inefficiency, accelerating drug development, modeling disease trajectories, and eventually automating the more repetitive layers of care. There’s even an irony: the very infrastructure needed to enable learning health systems would also finally make billing more accurate.

I’m not writing this to showcase some utopian vision of AI curing all disease. It’s the practical use of technology we already possess. Our limitation isn’t the models; it’s the missing data.

A handful of companies have bet their trillion-dollar valuations on this: OpenAI, Google, Amazon, Nvidia, Apple, Oracle. They are spending hundreds of billions a year on AI infrastructure and need high-volume, high-quality datasets to justify that investment. Healthcare produces oceans of exactly that kind of data, and most of it evaporates. The companies that learn to capture and structure it will define the next layer of healthcare infrastructure. Whether they integrate with Epic, build around it, or replace it is almost secondary.

What matters is that none of them are waiting for Epic.

Clinicians won’t either. Once tools exist that unify the data hospitals already generate, reduce workload, eliminate administrative drag, and answer the questions clinicians actually ask — What happened? Why did it happen? What should we do now? — the center of gravity will shift. Clinicians will live inside those tools, not inside an interface built for billing.

Epic can still exist, but it doesn’t need to function as healthcare’s operating system. There’s precedent for this in every major industry: the core orchestration/data layer eventually recedes into the background while workflow and data intelligence move up the stack. At that point, the EHR becomes background infrastructure or middleware. The intelligence/workflow layer becomes the real operating system. Epic will undoubtedly resist this shift, yet its attempts to maintain total control of the clinician interface will ultimately collide with the utility and data gravity of AI-native systems.

Epic becomes the backend: essential, invisible, and no longer the place where the practice of medicine occurs.

Regulatory modernization around HIPAA, interoperability, and data liquidity will be essential, but that is a conversation for another essay.

Epic isn’t vanishing tomorrow. Large institutions rarely do. But its relevance is eroding in the only domain that will matter over the next decade: the ability to harness data at a scale and fidelity that makes AI transformative. It can keep its commandments, preserve its culture, and reject outside capital — it just can’t do all that and remain the central platform of hospital data in an AI-native future.

Mark Twain on Politics and Diapers

Nursing Programs excluded from Professional Degree Status

Quote of Day – On Right vs Popular

Happy Thanksgiving

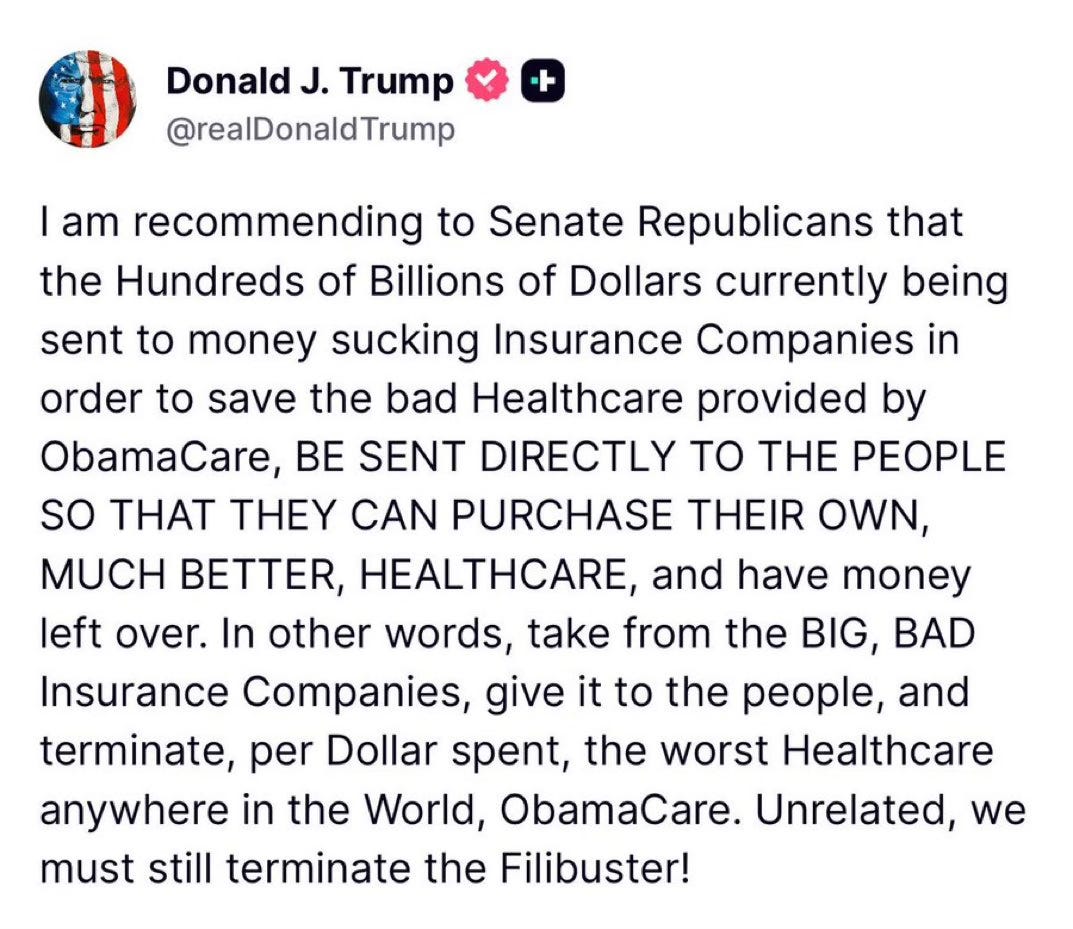

Big Insurance Reform: It’s Not Just The Libs

I know plenty of people who are politically right-of-center – and they want to rein in Big Insurance just as much as people to the left.

Some of my closest family and friends have nearly polar opposite political beliefs than mine. And these are not family members I’m only with on holidays (like during Thanksgiving dinner later this week) or friends I only see on Facebook. These are people I love and communicate with weekly — sometimes daily. They’re my people.

And I’d say that my people largely fall into two distinct right-of-center sub groups:

The first group:

USDA grass-fed Trump supporters who like Jeanine Pirro and Blue Lives Matter bumper stickers.

And the second group:

Nonpolitical and anti-establishment 20-30 somethings who make their own beef-tallow.

(And both groups are patient enough to keep a Bernie-t-shirt-owning-lib, who listens to The Daily (like myself) in their lives.)

We don’t all agree on vaccines. We don’t all agree on the Gulf of America. And none of them agree with my mullet. But what we all do agree on is that through backroom deals and moneyed influence, big corporations pull Washington’s levers and squeeze American families at every chance they get – all to make their Wall Street investors and executives richer. And, as readers of HEALTH CARE un-covered undoubtedly know, Big Insurance may be the perfect example of those deals and influence.

That’s where my people and I meet in our venn diagram. While we have many sticking points, Big Insurance is not one of them.

And this is not just qualitative on my end. Poll after poll proves that my people are not the exception to the rule. An October KFF poll showed that a majority of Republicans who align with the MAGA movement (57%) said Congress should have extended the enhanced premium tax credits for Affordable Care Act (ACA) plans, and a new study by Undue Medical Debt found that 62% of Republicans blame health insurance companies the most for the medical debt crisis in the country.

The deeds of the health insurance industry have grown so rotten and their stench so unavoidable that even the President has caught a whiff. On Truth Social last month, President Trump posted about “BIG,” “BAD” and “Money sucking” health insurance companies. His message reverberated in the media and on Wall Street and helped bring this issue even more to the forefront.

But here’s the thing: Trump’s post isn’t the tip of the spear but rather the caboose following a long train of Republicans (and their voters) who as of late have begun to focus on Big Insurance. In the last six months, we’ve seen Representative Marjorie Taylor Green call on Republicans to take on Big Insurance, former Representative Mark Green (R-TN) introduce legislation to crack down on Big Insurance’s prior authorization tactics, and Pam Bondi’s Department of Justice open a criminal investigation into UnitedHealth Group’s Medicare Advantage business – all moves that have been historically uncharacteristic of their political bents but nonetheless are, in one way or another, raising the heat on Big Insurance.

If the latest news out of Washington tells us anything, it’s that conservatives are largely on the same side as many of the most liberal voices when it comes to health insurance reforms.

While my people may not speak the same health care language or advocate the exact same solutions that many health care reform advocates or left-of-center folks would raise, the differences are largely just in the terminology used. For instance, my people are not going to mention Medicare for All or a public option as an answer to our country’s health care woes. Those phrases have been carefully tarred and feathered by the insurance industry as “socialism” to hold back both centrist and Republican voters and policymakers from putting guardrails in place that would cut into the industry’s immense profits. But again, it’s the terminologies that have been discredited – not the sentiment behind them.

On more than one occasion, when talking with my people about health insurers, they have straight-up volunteered that they think “insurance companies should be outlawed.” That belief, last time I checked, was to the left of even Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sander’s proposals to finally establish universal coverage for every American by expanding Medicare to cover all of us.

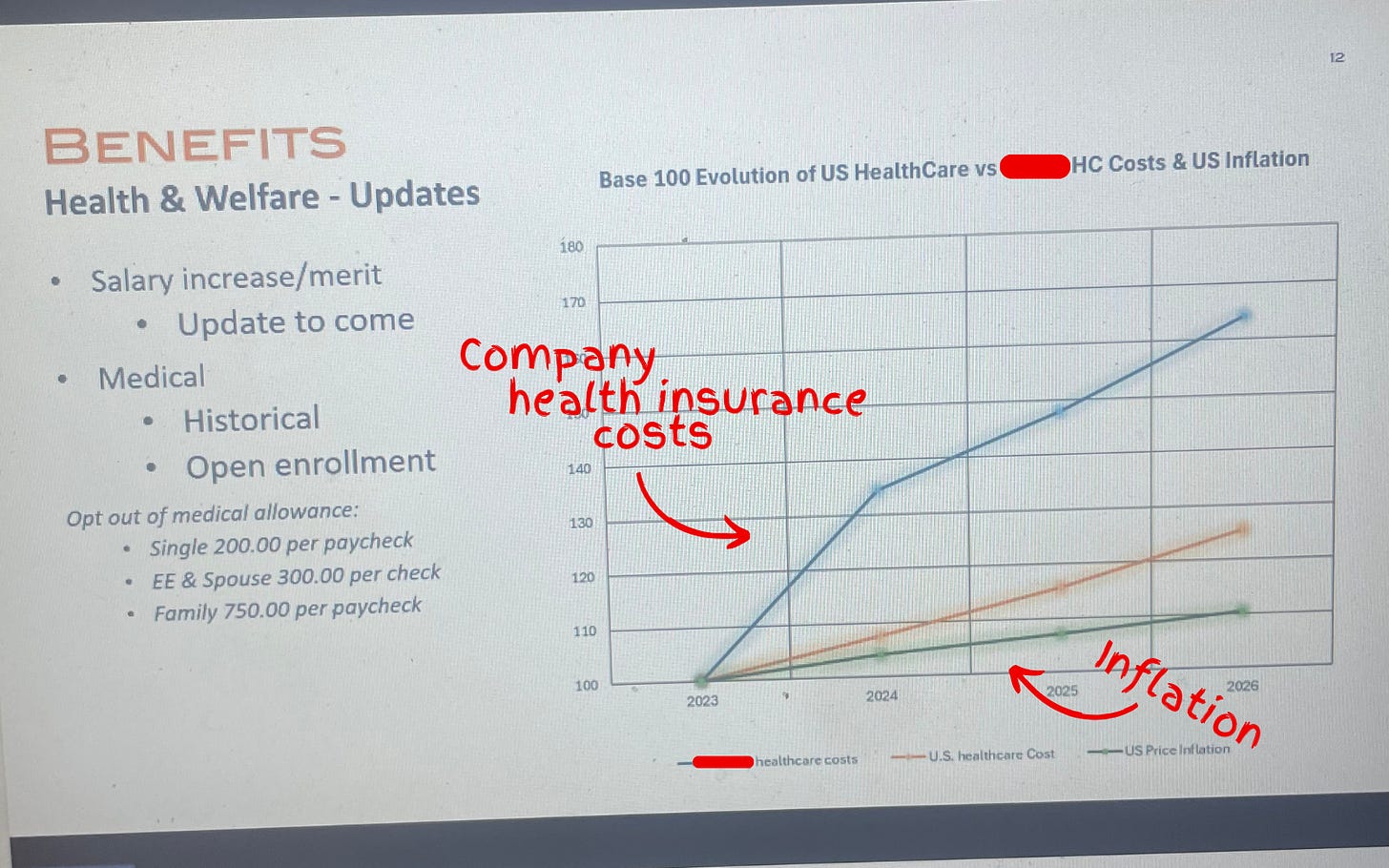

Another one of my people, who handles financials for the North American-sector of a sizable global company in the home-technology space, FaceTimed me last week to show me his computer screen while he was crunching the companies’ health care costs.

In anticipation for a company-wide town hall, he had to make a slide showing that the health insurance costs for his company’s U.S.-side had increased (on average) 20% over the past several years – including a projected 25% jump in 2026. He couldn’t believe it. “Show this to Wendell,” he said.

And that’s the thing:

Nobody can believe how out-of-control Big Insurance has become.

Where my people and I meet

It’s fair to say that I think more about health care policy than the average bear. And it’s true that my people have had me in their ear talking about these issues for nearly a decade. But as I noted above, polling shows that while certain solutions may not be as popular, the desire for action is clear and exists sans my yapping.

Over years of conversations, there have been some major themes that have stuck. I will list them below:

- Big Insurance is the villain in health care: With its army of slick lobbyists and spokesmen on TV, Big Insurance is the epitome of the D.C.-swamp monster that so many Americans disdain. Between 2014 and 2024, just seven for-profit health insurers amassed $543.4 billion in profits (of which they spent $618 million on lobbying during that time) all while 100 million Americans owe $220 billion in medical debt and Americans’ life expectancy is ranked 48th in the world.

- Big Insurance and it’s cushy government handouts: Nearly all of Big Insurance’s growth has come from contracts it engineers with the federal and state governments in the form of managing Medicaid, Medicare Advantage and some Veteran health services. These contracts are not the invisible hand of the free market but rather cushy government handouts that have allowed just seven for-profit health insurance conglomerates to capture $10.192 trillion in revenues between 2014 and 2024.

- Big Insurance’s business practices: Health insurance companies like UnitedHealth Group, Cigna and Aetna deploy rigid artificial intelligence (AI) programs to sideline doctors and automate denials, offshore jobs and employ folks in India and the Philippines to deny American’s care while they use American’s premium and tax dollars to boost million dollar C-suite compensation packages and buy back their own stocks.

- Big Insurance has grown too big: Big Insurance companies are buying up the entire health care landscape – from physician practices to pharmacies. That is why independent physicians are an endangered species and why an independent pharmacy closes nearly every day in this country.

- Big Insurance hurts the little guy: American small businesses often see double-digit yearly increases in health insurance costs that stifle Main Street America’s growth and stop Americans from being entrepreneurs altogether. And, not to mention, if businesses weren’t being raked over the coals for more premium dollars year after year, more money could be paid to workers.

I included this list because I think we are at a watershed moment in the health care debate and reforming Big Insurance is no longer a wedge issue. It’s a bridge issue.

I don’t know what comes next

Because the long standoff between Republicans and Democrats to open the government finally came to an end this month – without the ACA subsidy extensions – Big Insurance reform (and health care reform broadly) has become an unaddressed priority in American politics.

In the current moment, if Republican electeds were smart, they’d read the writing on the wall and focus on rooting out an actual source of widespread waste, fraud and abuse found in health insurance companies’ private Medicare Advantage, Medicaid and military businesses. That’s an issue that polls incredibly well with conservatives. Just tackling Medicare Advantage, for example, could save taxpayers somewhere between $80 and $140 billion annually. For reference, the DOGE website claims it has only clawed back $214 billion in total since January.

Republicans could also work with their political opposites (and fulfill a campaign promise) to pass a worthwhile health insurance reform package that builds on (or possibly replace) the consumer protections of ACA and fills the loopholes of well-intended rules that have been exploited and manipulated by Big Insurance.

And it wouldn’t be a one-party trick. For what it’s worth, I think most Democrats in Washington would be on board with anything that lessens the corporate grip Big Insurance has on our country’s public programs and improves the ACA. In the last year, we’ve already seen Democrats link with the country’s current controlling party to introduce bills that would bring meaningful change to Big Insurance:

- Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) introduced legislation that would stop health insurance companies from owning pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs);

- Senators Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Bill Cassidy, M.D. (R-LA) introduced the No UPCODE Act to curb taxpayer-sponsored overpayments to health insurers; and

- Representatives Nannette Barragan (D-CA) and Mariannette Miller-Meeks, M.D. (R-IA) (among other legislators) reintroduced The DRUG Act to stop insurance companies from driving up drug prices.

These unlikely partnerships in Washington are happening because what my people (and all people) want is a health insurance system that guarantees comprehensive coverage for all of us, without forcing folks to choose between biopsies or groceries. Everybody I know – left, right and in between – wants a health care system that doesn’t bury families under mountains of medical bills or force them to attend unnecessary funerals. And all rational people want an insurance system that doesn’t buy off its buddies in Washington to serve their Wall Street daddies.

I want to scream from the mountaintops that health insurance reform is not just a moral or economic issue. It’s a winning issue.

Americans have had it. Most of Washington seems motivated. And now is the time for health care, patient and consumer advocates to change their tune and stop (just) preaching to the choir. Advocates for reform need to get their message to the corners of the country that they may have written off — or found too difficult to bridge — because the ground for health care reform is fertile for change. And I think all people are ready.

Thanksgiving is in a few days. And in times of heightened political polarization, the dinner table – filled with folks sharing a myriad of different opinions – can become a battleground between courses of mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie. But if I can gleam anything from what I see as a bi-partisan kumbaya against Big Insurance, it’s that even with all the reported divisiveness, we have one less thing to argue about.

And because of that – I don’t know what comes next – but what I do know is that the 2026 midterms and the 2028 presidential election will be about health insurance reform. And whichever political party takes that seriously is going to seize the day.