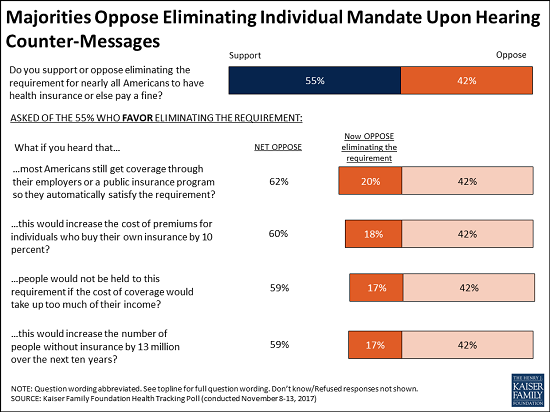

he tax legislation reported by the Senate Finance Committee last week included repeal of the individual mandate, which was created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and requires individuals to obtain health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that this proposal would cause large reductions in insurance coverage, reaching 13 million people in the long run.

Supporters of repealing the individual mandate have argued that the resulting reductions in insurance coverage are not a cause for concern because they would be voluntary. Rigorous versions of this argument acknowledge that individuals who drop coverage would lose protection against high medical costs, find it harder to access care, and likely experience worse health outcomes, but assert that the very fact that these individuals would choose to drop insurance coverage shows that they will be better off on net. On that basis, advocates of repealing the mandate claim that its repeal would do no harm. However, this argument suffers from two serious flaws.

The first flaw in this argument is that it assumes individuals bear the full cost of their decisions about whether to obtain insurance coverage; in fact, one person’s decision to go without health insurance coverage shifts costs onto other people. Notably, CBO has estimated that the departure of healthy enrollees from the individual market spurred by repeal of the individual mandate will increase individual market premiums by 10 percent, causing some in that market to involuntarily lose coverage and causing those who remain to bear higher costs. In addition, many of those who become uninsured will end up needing health care but not be able to pay for it, imposing costs on other participants in the health care system. Because individuals who choose to become uninsured do not bear the full cost of that decision, they may choose to do so even in circumstances where the benefits of coverage—accounting for its effects on both the covered individual and the rest of society—exceed its costs.

The second flaw in this argument is that it assumes individual decisions about whether to purchase health insurance coverage reflect a fully informed, fully rational weighing of the cost and benefits. In fact, there is strong reason to believe that many individuals, particularly the healthier individuals most affected by the mandate, are likely to undervalue insurance coverage. This likely reflects a variety of well-documented psychological biases, including a tendency to place too much weight on upfront costs of obtaining coverage (including the “hassle costs” of enrolling) relative to the benefits insurance coverage would provide if the individual got sick and needed care at some point in the future. It is therefore likely that many people who would drop insurance coverage due to repeal of the individual mandate would end up worse off, even solely considering the costs and benefits to the individuals themselves.

The considerations described above mean that, in the absence of subsidies, an individual mandate, or some combination of the two, many people will decline to obtain insurance coverage despite that coverage being well worth society’s cost of providing it. Furthermore, unless the current subsidies and individual mandate penalty provide too strong an incentive to obtain coverage that results in too many people being insured—a view that appears inconsistent with the available evidence—then reductions in insurance coverage due to repealing the individual mandate would do substantial harm.

The remainder of this analysis takes a closer look at the two flaws in the argument that reductions in insurance coverage caused by repeal of the individual mandate would do no harm. The analysis then discusses why these considerations create a strong case for maintaining an individual mandate.

INDIVIDUAL DECISIONS TO DROP INSURANCE COVERAGE IMPOSE SUBSTANTIAL COSTS ON OTHER PEOPLE

As noted above, supporters of repealing the individual mandate have often argued that the resulting reductions in insurance coverage would do no harm because they are the outcome of voluntary choices. One major flaw in this argument is that one person’s decision to drop insurance coverage imposes costs on other people through a pair of mechanisms: increases in individual market premiums and increases in uncompensated care. I discuss each of these mechanisms in greater detail below.

Increases in individual market premium reduce coverage and increase others’ costs

Repealing the individual mandate would reduce the cost of being uninsured and, equivalently, increase the effective cost of purchasing insurance coverage. That increase in the effective cost of insurance coverage would, in turn, cause many people to drop coverage. Because individuals with the most significant health care needs are likely to place the highest value on maintaining insurance coverage, the people dropping insurance coverage would likely be relatively healthy, on average. In the individual market, those enrollees’ departure would raise average claims costs, requiring insurers to charge higher premiums to the people remaining in the individual market.[1]

CBO estimates that, because of this dynamic, repealing the individual mandate would increase individual market premiums by around 10 percent. Those higher premiums would push some enrollees who are not eligible for subsidies out of the individual market. Higher premiums would impose large costs on unsubsidized enrollees who remained in the ACA-compliant individual market—around 6 million people—while increasing federal costs for subsidized enrollees who remain insured.[2]

CBO’s estimates are at least qualitatively consistent with empirical evidence on the effects of the individual mandate. Perhaps the best evidence on this point comes from Massachusetts health reform. Research examining the unsubsidized portion of Massachusetts’ individual market estimated that Massachusetts’ individual mandate increased enrollment in the unsubsidized portion of its individual market by 38 percent, reducing average claims costs by 8 percent and premiums by 21 percent. Similarly, research focused on the subsidized portion of Massachusetts’ market found that the mandate appears to have been an important motivator of enrollment, particularly among healthier enrollees.

Direct evidence on the effects of the ACA’s mandate is relatively scant because it is challenging to disentangle the effect of the mandate from the effect of other policy changes implemented by the ACA. However, it is notable that the uninsured rate among people with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty level fell by almost one-third from 2013 to 2015. This trend is consistent with the view that the ACA’s individual mandate has increased insurance coverage since these individuals are not eligible for the ACA’s subsidies, and implementation of the ACA’s bar on varying premiums or denying coverage based on health status, taken on its own, would have been expected to actually reduce insurance coverage in this group. Because this estimate applies to only a relatively small slice of the population, it cannot easily be used to determine the total effect of the individual mandate on insurance coverage, but it does suggest that the mandate has had meaningful effects.

Repealing the individual mandate could also cause broader disruptions in the individual market for some period of time. Insurers would find it challenging to predict exactly what the individual market risk pool would look like after repeal of the mandate. Some insurers might elect to limit their individual market exposure until that uncertainty is resolved, particularly since the Trump Administration has signaled an intent to pursue other significant policy changes affecting the individual market. That uncertainty could cause some insurers to withdraw from the market, potentially leaving some enrollees without any coverage options. Alternatively, insurers could elect to raise premiums by even more than they expect to be necessary (e.g., by more than the CBO 10 percent estimate cited above) to ensure that they are protected in all scenarios, with significant costs to both individuals and the federal government. It is uncertain how widespread these types of broader disruptions would be in practice, but they are possible.

It is important to note that one person’s decision about whether to purchase individual market coverage affects the premiums faced by others because of a conscious policy choice: the decision to bar insurers from varying premiums or denying coverage based on health status. Without those regulations, individual coverage decisions would have little or no effect on the premiums charged to others. But policymakers and the public have, appropriately in my view, concluded that these regulations perform a valuable social function by ensuring that health care cost burdens are shared equitably between the healthy and the sick. Having made that decision, other aspects of public policy must take account of the fact that one person’s decision to go uninsured has consequences for the market as a whole.

Some newly uninsured individuals would need care, but be unable to pay for it

Dropping insurance coverage also allows individuals to shift a portion of the cost of the care they receive onto others in the form of uncompensated care. Even in the group of comparatively healthy individuals who elect to drop their coverage, some will get sick and need health care. Some of these individuals might be able to pay for that care out of pocket, but others—particularly those who get seriously ill—would likely be unable to pay for it. In some cases, that would cause these individuals to forgo needed care, but in other cases they would receive care without paying for it, either due to the legal requirement that hospitals provide care in emergency situations or through various other formal and informal mechanisms. (Although individuals would often still be able to access care without paying for it, they would frequently still be billed for that care, with potential downstream consequences for their ability to access credit.)

Uninsured individuals receive large quantities of uncompensated care in practice. Estimates based on the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey indicate that a non-elderly individual uninsured for the entire year received $1,700 in uncompensated care, on average, during 2013. Consistent with that fact, increases in the number of uninsured individuals increase the amount of uncompensated care. In the context of the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, a randomized controlled trial of the effects of expanded Medicaid coverage, having Medicaid coverage was estimated to reduce the amount of uncompensated care an individual receives by almost $2,200 per year, on average. Quasi-experimental research has similarly found that increases in the number of uninsured individuals in a hospital’s local area increase the amount of uncompensated care a hospital delivers and that the expansion in insurance coverage achieved by the ACA substantially reduced hospitals’ uncompensated care burdens.

Precisely who bears the cost of uncompensated care, particularly in the long run, is not entirely clear. A portion of uncompensated care costs are borne by federal, state, and local government programs and, therefore, are ultimately borne by taxpayers. In 2013, around three-fifths of uncompensated care was financed by federal, state, and local government programs explicitly or implicitly aimed at this purpose. Increases in uncompensated care burdens are likely to lead to increases in spending on these programs. In some cases, those increases will happen automatically. For example, CBO finds that repealing the individual mandate will increase federal spending on the Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) program, which is intended to defray uncompensated care costs, by $44 billion over the next ten years because the formula for determining DSH payments depends on the uninsured rate. In other cases, changes may occur more indirectly, perhaps because higher uncompensated care burdens create political pressure to expand these programs (or make it harder to cut them).

The impact of uncompensated care therefore depends to a significant degree on how non-profit hospitals cope with reduced operating margins. Evidence on this point is relatively limited. However, in instances where increases in uncompensated care burdens cause providers to incur outright losses, they are likely to ultimately force facilities to close, which could reduce access to care or increase prices charged to those enrolled in private insurance by reducing competition. In instances where increases in uncompensated care burdens merely trim positive operating margins, lower margins presumably force hospitals to reduce capital investments or to reduce cross-subsidies to other activities such as medical education or research.Recent research focused on the hospital sector, which accounts around three-fifths of all uncompensated care, suggests that providers also bear a significant portion of uncompensated care costs in the form of lower operating margins. However, this does not imply that uncompensated care costs are ultimately borne by hospitals’ owners. Indeed, this research finds that reductions in operating margins in response to increases in uncompensated care occur almost exclusively among non-profit hospitals, plausibly because for-profit hospitals are adept at locating in geographic areas where the demand for uncompensated care is relatively low. (Greater distortions where providers choose to locate and what services they choose to offer may be an important cost of increased uncompensated care.)

INDIVIDUAL DECISIONS TO DROP INSURANCE COVERAGE MAY HARM THE INDIVIDUALS THEMSELVES

The argument that reductions in insurance coverage due to repeal of the individual mandate do no harm because they are voluntary has a second important flaw; specifically, this argument assumes that individual decisions about whether to obtain health insurance coverage reflect a fully informed, fully rational weighing of the costs and benefits. There is strong reason to doubt that assumption.

Economists commonly note that many people decline to take-up health even in settings where that coverage is free or nearly so. For example, analysts at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) have estimated that, in 2016, there were 6.8 million people who were eligible for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program, but not enrolled in those programs, despite the fact that these programs had negligible premiums. Similarly, for this year’s Marketplace open enrollment period, analysts at KFF estimated that among uninsured individuals eligible to purchase Marketplace coverage, around two-fifths could obtain a bronze plan for a premium of zero, but few expect all of these individuals to enroll.

This type of behavior is very challenging to explain as the outcome of a fully informed, fully rational decision-making process. The fact that individuals who do not purchase insurance coverage can shift significant costs to others, as discussed above, can help explain why some individuals value insurance at less than the cost of providing it. But these factors cannot explain why enrollees would decline to obtain coverage that is literally free to them. In principle, “hassle costs” of enrolling in coverage could explain decisions to forgo coverage in these instances, but those hassle costs would need to be implausibly large to explain a decision to forgo an offer of free insurance coverage.

Precisely why individuals decline to take up insurance coverage even in settings where it seems clearly in their interest to do so is not fully understood. This review article catalogues a wide variety of psychological biases that may play a role, but three seem particularly important in this context:

- Present bias: Economists have documented that individuals generally exhibit “present bias,” meaning that they place a large weight on current costs and benefits relative to similar costs and benefits in the future. In the context of insurance coverage, this type of bias is likely to cause individuals, particularly those who are currently healthy, to place too much weight on the upfront premium and hassle costs required to enroll in health insurance relative to the benefit of having insurance coverage if they get sick at some point in the future. This may cause individuals to decline to obtain insurance coverage even when it is in their economic interest, including in instances where the premium required to enroll is literally zero.

Overweighting of small up front hassle costs appears to lead suboptimal decisions in many economic settings, but the retirement saving literature provides a particularly striking example. Simply being required to return a form to enroll in an employer’s retirement plan has been documented to sharply reduce take-up of that plan, even in circumstances where employees forgo hundreds or thousands of dollars per year in employer matching contributions by declining to participate.

- Overoptimistic perceptions of risk: One core function of health insurance is to provide protection against relatively rare, but very costly, illnesses. Indeed, a large fraction of the total value of a health insurance contract is delivered in those states of the world. In 2014, around 5 percent of the population accounted for around half of total health care spending.[3] But because these events are comparatively rare, many individuals, particularly healthier individuals, may have difficulty forming accurate perceptions of the risks they face. Research on Medicare Part D has found that individuals tend to place too much weight on premiums relative to expected out-of-pocket costs when choosing plans, providing some evidence that individuals do indeed underestimate risk (although research focused on insurance products other than health insurance has concluded that individuals may sometimes overestimate risk). Like present bias, misperceptions of risk can cause hassle or premium costs to receive too much weight relative to the actual benefits of coverage.

- Inaccurate beliefs about affordability: Enrollees could also have inaccurate information about the availability of coverage. Survey evidence has suggested that, as of early 2016, almost 40 percent of uninsured adults were unaware of the existence of the ACA’s Health Insurance Marketplaces. Additionally, approximately two-thirds of those who were aware of the Marketplaces had not investigated their coverage options, with most saying that they had not done so because they did not believe that they could afford coverage. Individuals’ beliefs about whether coverage is affordable may be accurate in some instances, but it is likely that they are not accurate in many other cases. Inaccurate beliefs may cause many individuals to fail to investigate their coverage options, including some who are eligible for free or very-low-cost coverage.

REDUCTIONS IN INSURANCE COVERAGE FROM REPEALING THE INDIVIDUAL MANDATE WOULD DO SUBSTANTIAL HARM

The factors identified above provide strong economic rationale for implementing some combination of subsidies and penalties to strengthen the financial incentive to obtain health insurance coverage. These policy tools can compensate for the fact that individual decisions to go without coverage do not account for the ways in which those decisions increase costs for others. Similarly, in many (though not all) instances, financial incentives can help counteract psychological biases that cause individuals to go without insurance coverage even when it is against their own economic interest.

This discussion does not, of course, speak directly to how large subsidies and penalties should be. At least in theory, it is possible to overcompensate for the factors catalogued in the preceding section by creating too large an incentive to obtain coverage and thereby causing too many people to become insured. This occurs if the cost of the additional health care individuals receive when they become insured plus the administrative costs of providing that coverage exceeds the health benefits of the additional health care and the improved protection against financial risk.

Estimating the optimal size of subsidies and penalties is beyond the scope of this analysis. However, it is notable that virtually no one in the current policy debate is arguing that the United States insures too many individuals. Furthermore, there is reason to doubt that this is an empirically relevant concern. For example, the research on Massachusetts health reform by Hackmann, Kolstad, and Kowalski that was discussed earlier used their estimates to calculate the “optimal” mandate penalty to apply to unsubsidized enrollees. They conclude that just offsetting adverse selection justifies a mandate penalty similar in size to the one included in the ACA; also accounting for either uncompensated care or imperfections in consumer decision making could justify a considerably larger penalty.

It therefore seems difficult to justify repealing the individual mandate on the grounds that current policies provide an excessive overall incentive to obtain insurance coverage. Of course, policymakers might believe that it would be preferable to swap the mandate for larger subsidies, perhaps because they believe that it is inappropriate to penalize individuals for not obtaining coverage. In principle, sufficiently large increases in subsidies could offset the reduction in insurance coverage that repealing the individual mandate would cause. But such an approach would require large increases in federal spending since it would keep insurance enrollment at its current level by providing larger subsidies to each enrolled individual. In any case, the Senate Finance Committee bill does not take this approach. Rather than increasing spending on insurance coverage programs to mitigate coverage losses, the bill uses the reduction in spending on coverage programs caused by repealing the mandate (which results from lower enrollment in those programs) to finance tax cuts.