President Trump’s planned executive order on ObamaCare is worrying supporters of the law and insurers, who fear it could undermine the stability of ObamaCare.

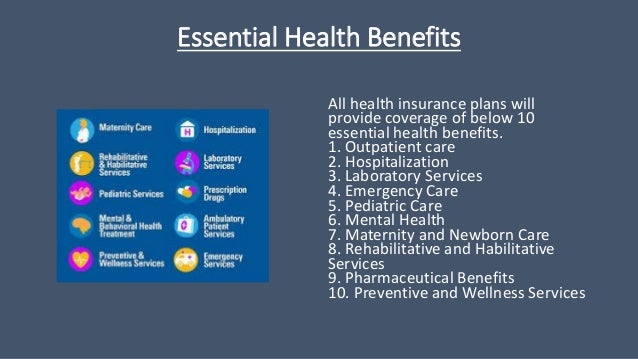

Trump’s order, expected as soon as this week, would allow small businesses or other groups of people to band together to buy health insurance. Some fear that these association health plans would not be subject to the same rules as ObamaCare plans, including those that protect people with pre-existing conditions.

That would make these plans cheaper for healthy people, potentially luring them away from the ObamaCare market. The result could be that only sicker, costlier people remain in ObamaCare plans, leading to a spike in premiums.

“If this executive order is anything like the rumors then it could have a huge impact on stability of the individual insurance market,” said Larry Levitt, a health policy expert at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Andy Slavitt, a former top health-care official in the Obama administration, warned that insurers could drop out of the Affordable Care Act markets because of the order.

“I am now hearing that the Executive Order may cause insurers to leave ACA markets right away,” Slavitt tweeted on Sunday.

Slavitt argues the order is part of Trump’s broader effort to undermine ObamaCare. He said the order could accomplish through executive action what Congress failed to do through legislation.

But supporters say Trump’s move could unleash the free market and lower prices for consumers.

Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) has been pushing for the order, arguing it is something Trump can do without Congress to give people an alternative to ObamaCare.

“This is something I’ve been advocating for six months,” Paul said on MSNBC in late September.

“I think it’s bigger than Graham-Cassidy, it’s bigger than any reform we’ve even talked about to date, but hasn’t gotten enough attention,” Paul added, referring to the failed Republican repeal-and-replace bill co-sponsored by Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) and Bill Cassidy (R-La.).

Paul said allowing more people to band together to purchase health insurance gives them more leverage to lower premiums than when people are buying coverage on their own.

The National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), which has long opposed ObamaCare, supports expanding association health plans and has been advocating for action.

“Allowing people more affordable arrangements is not a bad thing,” said Kevin Kuhlman, director of government relations at the NFIB. He said fears about undermining ObamaCare markets are “overblown.” His group is waiting to review the details of the order, which he said he expects to be issued on Thursday.

Association health plans already exist, but Trump’s order could allow them to expand and get around ObamaCare rules, creating plans that are only for healthy people.

Experts pointed to the Tennessee Farm Bureau, which currently offers an association health plan in the state that, through a loophole, does not have to follow ObamaCare rules.

The plan has about 73,000 enrollees and may be one of the reasons that Tennessee’s ObamaCare market has struggled, according to researchers at Georgetown University.

There is still much uncertainty about the order. Many observers doubt that Trump has the power to change much on his own.

Tim Jost, a health law expert at Washington and Lee University, said it is hard to imagine how the White House could find the legal authority to expand association health plans to individuals. The move would likely draw legal challenges.

A more likely action, Jost said, would be to expand association health plans so that it is easier for small groups to form them. That could destabilize the small group insurance market but would be a less sweeping step than expanding association health plans to individuals.

Given the limits on his authority, Trump is likely to direct agencies, including the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Labor, to issue guidance or regulations. Those additional steps will prolong the process.

Insurers are worried about the potentially destabilizing effects of the order. Lobbyists said insurers had begun quietly working on the issue and talking to the administration but do not yet know how far-reaching the effects would be.

It is possible there could be legal challenges to the regulations. The order would change the interpretation of a 1974 law called the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. That interpretation could be challenged in court, for example if the order sought to allow individuals, not just small groups, to join association health plans.

“There will likely be challenges,” said Kevin Lucia, a professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Health Insurance Reforms.

Lucia said the planned order, in combination with other steps the Trump administration is taking, like cutting back on outreach efforts, “really undermines the future of the individual market.”

A sicker group of enrollees remaining in the ObamaCare plans poses problems.

The changes “will lead to less [insurers] playing in this market and potentially a sicker risk pool which translates to higher premiums,” Lucia said.

Cori Uccello, senior health fellow at the American Academy of Actuaries, said that one aspect to watch in the order is when the changes will take effect. Insurers have already set their prices and made plans for 2018.

“Anything that applied to 2018 would be incredibly destabilizing,” she said. “It would still be destabilizing in 2019 but people would know ahead of time.”