Last week, the war in Iran intensified and Kristi Noem’s tenure as DHS Secretary came to an unceremonious close. Perhaps lost in the noise was the February jobs report issued Friday by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. It showed a surprising decline in job growth prompting speculation the economy might have taken a downward turn. Some headlines….

- Payrolls unexpectedly fell by 92,000 in February; unemployment rate rises to 4.4% (CNBC)

- Employers Cut Jobs in Sign of a Shakier Economy (New York Times)

- Paychecks keep rising for American workers, providing boost to household budgets (Fox Business):

- The U.S. economy lost 92,000 jobs in February, stoking labor market worries (NBC News)

- The US economy lost 92,000 jobs in February and the unemployment rate rose to 4.4% (CNN)

Anticipation that the jobs report portends bad news for the economy followed the news cycle all day and through the weekend. And a few, like Axios, went further: “The surprise to many was where the biggest since job growth especially in healthcare and social assistance had buoyed the labor market for 3 years.” Others attributed the decline to hangovers from recent nursing strikes (USC Keck, Kaiser Permanente, MarinHealth) and layoffs by many health systems.

To industry insiders, the BLS jobs report’s capture of declines in healthcare hiring was no surprise. Operating cost reduction has been a strategic imperative in every hospital, long-term care, ancillary and medical group since the pandemic (2020). In tandem, investments in workforce productivity enhancements via technology-enabled workforce redesign and performance-based compensation have elevated human resource management to C-suite status in most organizations. It’s understandable:

Healthcare is capital intense: it needs appropriations from government and in-flows from employers and individual taxpayers to pay its bills. Most of that pays for its labor costs. Today, most Board agenda include updates on labor relations, human resource management issues and workforce adequacy—it’s standard fare. And all weigh options to outsource and devour progress reports from HR management on AI-enabled investments anticipated to reduce labor costs.

Healthcare is highly regulated, especially in workforce activities, and labor-management relationships impact organizational performance and reputation. Every sector in healthcare is regulated by combinations of federal, state and local rules, laws and agency directives that define roles, responsibilities, decision-rights and constraints of its workforce. It’s complicated by the politics of healthcare which avoids policy changes that threaten protections sought by each labor cohort in healthcare. Protecting funding and restricting infringement on scope of responsibility by unwanted outsiders is the primary rationale for professional society’ advocacy efforts. In hospital and long-term care settings, the healthcare workforce is a cast-system that keeps doctors at the top of the pyramid, licensed mid-levels in the middle and everyone else below. In other healthcare settings, executive-level designations dominate hierarchies, and in some Boards play roles in workforce structure and compensation schemes. Workforce modernization in most healthcare settings is acknowledged as a critical need but most default to layoffs and fail to enact a comprehensive strategy.

Looking ahead, technology will alter the status quo for workforce modernization efforts in healthcare:

1-Less dependence on physician recommendations. Might patients access customized clinical decision support tools more widely in the future and make more choices themselves (especially if incentives support self-care)? Might other sources of clinical counsel be more accurate, more accessible and less costly in the future, prompting acceptance (trust and confidence) by patients? Physicians and other caregivers will play key roles, but in concert with tools and processes that enable consumer engagement.

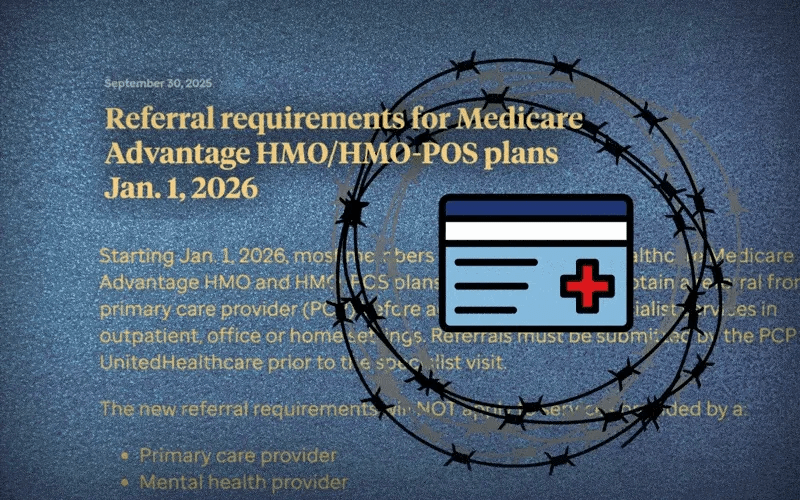

2-More access to verifiable cost, price and value information. The underlying costs and prices for healthcare services are unknown to their caregivers at the points of care so the majority of transactions require pre-authorization by a third-party adjudicator with payments that follow. Physicians bear no responsibility for advising patients about costs and prices: theirs is exclusively the domain of clinical counsel. Thus, labor costs in healthcare presume third party payments, middlemen, incapable self-care and work rules that reinforce old ways and torpedo better ways of work. Might the role and scope of insurer activity be integrated with delivery so that “costs and quality” are directly accountable to providers? Might primary and preventive health hubs (physical + behavioral + nutrition + prophylactic dentistry + self-care enablement + insurance) become the centerpieces of community health replacing traditional insurers and hospitals? Where will the workforce choose to work?

Per the Healthcare Workforce Coalition (www.healthcareworkforce.org), healthcare workforce shortages are a near and present danger to the U.S. health system: shortages of physicians, nurses and allied health professionals are significant, especially in rural areas. The 18-million who constitute the healthcare workforce today are being told to work harder with less. It’s no secret.

In the Affordable Care Act (2010), Title 5 (Section 5101), healthcare workforce modernization was authorized: “The purpose of this title is to improve access to and the delivery of health care services for all individuals…” Subtitle B authorized creation of a 15-member National Health Care Workforce Commission to recommend modernization policies. It would have coordinated workforce initiatives across federal agencies (HRSA, CMS, MedPAC, MACPAC, GAO, et al) along with states and private sector operators to address long-term issues and short-term execution challenges. The Commission never met because its funding was not authorized by Congress.

If the overall economy is dependent on healthcare to produce an appropriate share of job growth while reducing overall costs, modernizing its workforce is key. It must include unpaid caregivers, licensed and unlicensed providers and technology-enabled solution providers—not just traditional licensed professional groups and their academic partners. That’s not going to happen in the current political environment where each sector’s primary focus is protecting reimbursement and guarding against scope of practice threats.

The health system needs transformation. Workforce modernization is where to start.

Paul

P.S. My journey as a heart patient continues to teach me just how far we have to go as a “system.” Understanding what I have been billed for, by whom, when and why is like reading Russian. As best I can see, $267,490.30 has been charged by the hospital and 13 different doctors who’ve treated me in some way. How much I end up spending after rehab et al remains a mystery but it’s not remotely close to the hospital’s “price estimator” tool. Little wonder consumers are frustrated about healthcare costs pushing its affordability to the top of their Campaign 2026 concerns.