http://radio.wpsu.org/post/can-community-hospital-stick-its-mission-when-it-goes-profit

Mission Health, the largest hospital system in western North Carolina, provided $100 million in free charity care last year. This year, it has partnered with 17 civic organizations to deliver care for substance abuse by people who are low-income.

Based in bucolic Asheville, the six-hospital system also screens residents for food insecurity; provides free dental care to children in rural areas via the “ToothBus” mobile clinic; helps the homeless find permanent housing and encourages its 12,000 employees to volunteer at schools, churches and nonprofit groups.

Asheville residents say the hospital is an essential resource.

“Mission Health helped saved my life,” says Susan ReMine, a 68-year-old Asheville resident for 30 years who now lives in nearby Fletcher, N.C. She was in Mission Health’s main hospital in Asheville for three weeks last fall with kidney failure. And, from 2006 to 2008, a Mission Health-supported program called Project Access provided ReMine with free care after she lost her job because of illness.

After 130 years as a nonprofit with deep roots in the community, Mission Health announced in March that it was seeking to be bought by HCA Healthcare, the nation’s largest for-profit hospital chain. HCA owns 178 hospitals in 20 states and the United Kingdom.

The pending sale reflects a controversial national trend in the U.S. as hospitals consolidate at an accelerating pace and the cost of health care continues to rise.

“We understand the business reasons [for the deal], but our overwhelming concern is the price of health care,” says Ron Freeman, chief financial officer at Ingles Markets, a supermarket chain headquartered in Asheville with 200 stores in six states.

“Will HCA after a few years start to press the hospital to make more profit by raising prices? We don’t know,” Freeman says.

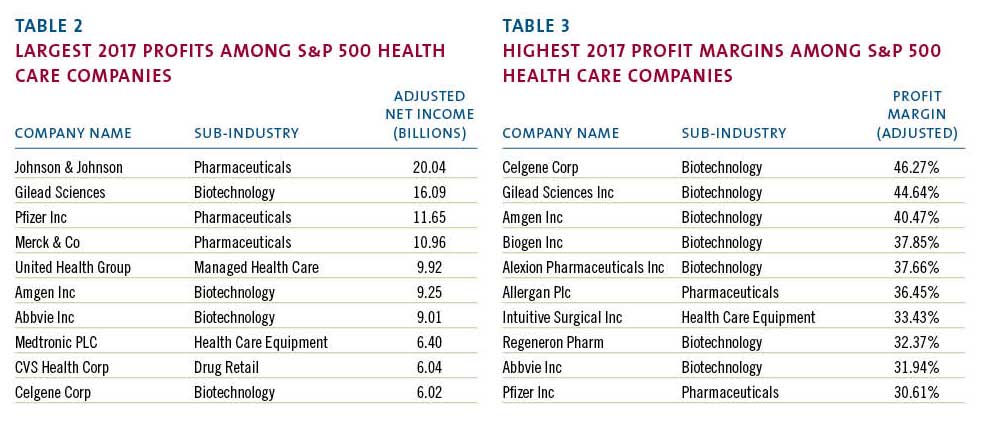

And the local newspaper, the Citizen Times, editorialized in March: “How does it help to join a corporation where nearly $3 billion that could have gone to health care instead was recorded as profit? … We would feel better were Western North Carolina’s leading health-care provider to remain master of its own fate.”

Across the U.S., the acquisition of nonprofit hospitals by corporations is raising concern among some advocates for patients and communities.

“The main motivation of for-profit companies is to grow so they can cut costs, get paid more and maximize profits,” says Suzanne Delbanco, executive director of the Catalyst for Payment Reform, an employer-led health care think tank and advocacy group. “They are not as focused on improving access to care or the community’s overall health.”

Merger mania across the U.S.

From 2013 to 2017, nearly 1 in 5 of the nation’s 5,500-plus hospitals were acquired or merged with another hospital, according to Irving Levin Associates, a health care analytics firm in Norwalk, Conn. Industry analysts say for-profit hospital companies are poised to grow more rapidly as they buy up both for-profits and nonprofits — potentially altering the character and role of public health-oriented nonprofits.

Nonprofit hospitals are exempt from state and local taxes. In return, they must provide community services and care to poor and uninsured patients — a commitment that is honored to varying degrees nationwide.

Of the nation’s 4,840 general hospitals that aren’t run by the federal government, 2,849 are nonprofit, 1,035 are for-profit and 956 are owned by state or local governments, according to the American Hospital Association.

In 2017, 29 for-profit companies bought 18 for-profit hospitals and 11 not-for-profits, according to an analysis for Kaiser Health News by Irving Levin Associates.

Sales can go the other way, too: 53 nonprofit hospital companies bought 18 for-profits as well as 35 nonprofits in 2017.

A recent report by Moody’s Investors Service predicted stable growth for for-profit hospital companies, saying they are well-positioned to demand higher rates from insurers and have less exposure to the lower rates paid by government insurance programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. In contrast, a second Moody’s report downgraded — from stable to negative — its 2018 forecast for the not-for-profit hospital sector.

‘We wanted to thrive, and not just survive’

Ron Paulus, Mission Health’s president and CEO, says he and the hospital’s 19-member board concluded last year that the future of Mission Health was iffy at best without a merger.

HCA declined to make anyone available for an interview but provided this written statement: “We are excited about the prospect of a transaction that would allow us to support the caliber of care they [Mission Health hospitals] have been providing.”

Driving Mission Health’s decision, Paulus says, were strained finances and the board’s strong feeling that the hospital needed to invest in new technology, modern data management tools and top clinical talent.

“We wanted to thrive and not just survive,” he says. “I had a healthy dose of skepticism about HCA at first. But I think we made the right decision.”

During the past four years, Paulus says, the company has had to cut costs — from between $50 million and $80 million a year — to preserve an “acceptable operating margin.” The forecast for 2019 and 2020, he says, saw the gap between revenue and expenses rising to $150 million a year.

Miriam Schwarz, executive director of the Western Carolina Medical Society, says many physicians in the area were surprised by the move and “are trying to grapple with the shift.”

“There’s concern about the community benefits, but also job loss,” Schwarz says. Still, she adds, the doctors in her region “do recognize that the hospital must become more financially secure.”

Weighed against community concerns is the prospect of a large nonprofit foundation created by the deal. Depending on the final price, the foundation could have close to $2 billion in assets.

Creation of such foundations is common when for-profit companies buy nonprofit hospitals or insurance companies. Paulus says the foundation created from Mission Health could generate $50 million or more a year to — among other initiatives — “test new care models such as home-based care … and address the causes of poor health in the community in the first place.”

In addition, HCA will have to pay upward of $10 million in state and local taxes.

Mixed results

Industry analysts say the hospital merger and consolidation trend nationwide is inevitable given the powerful forces afoot in health care.

That includes pressure to lower prices and costs and improve quality, safety and efficiency; to modernize information technology systems and equipment; and to do more to improve overall health.

But academics and consumer advocates say hospital consolidation yields mixed results. While mergers — especially purchases by for-profit companies — provide much-needed capital and financial stability, competition is stifled, and that’s often led to higher prices.

Martin Gaynor, a professor of economics and health policy at Carnegie Mellon University, and colleagues examined 366 hospital mergers from 2007 to 2011 and found that prices were, on average, 12 percent higher in areas where one hospital dominated the market versus areas with at least four rivals. Another recent study found that 90 percent of U.S. cities today have a “highly concentrated” hospital market. Asheville is one, and Mission Health is dominant there.

“The evidence is overwhelming at this point,” Gaynor says. “Mergers solve some problems for hospitals, but they don’t make health care less expensive or better. In fact, prices usually go up.”

Mission Health CEO Paulus says he believes HCA is committed to restraining price increases and the growth in costs.

If no obstacles arise, Paulus says, HCA’s purchase of Mission Health would be formalized in August and finalized in November or December, pending state regulatory approval.