https://mailchi.mp/burroughshealthcare/pc9ctbv4ft-1576037?e=7d3f834d2f

It’s 2018 and health insurance remains a major conundrum for America’s leaders, one hot political potato. Our current health system is worth $3.2 trillion to our economy — the most “valuable” in the world — but nearly 44 million people are without health insurance and our life expectancy falls behind thirty-six other nations.

The question remains: How can that be? And is healthcare really “a right” of all Americans?

Many other countries have successfully adopted single-payer systems, which means that no one is without coverage. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) is busy answering questions about his Medicare for All (M4A) platform, joined frequently by supporter and fellow democratic socialist and New York Congressional candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY).

“Health care must be recognized as a right, not a privilege,” he writes on his platform’s web page. “Every man, woman, and child in our country should be able to access the health care they need regardless of their income. The only long-term solution to America’s health care crisis is a single-payer national health care program.”

Summing it all up that way sounds very appealing, but making such a change would entail a seismic shift.

How Do We Really Feel?

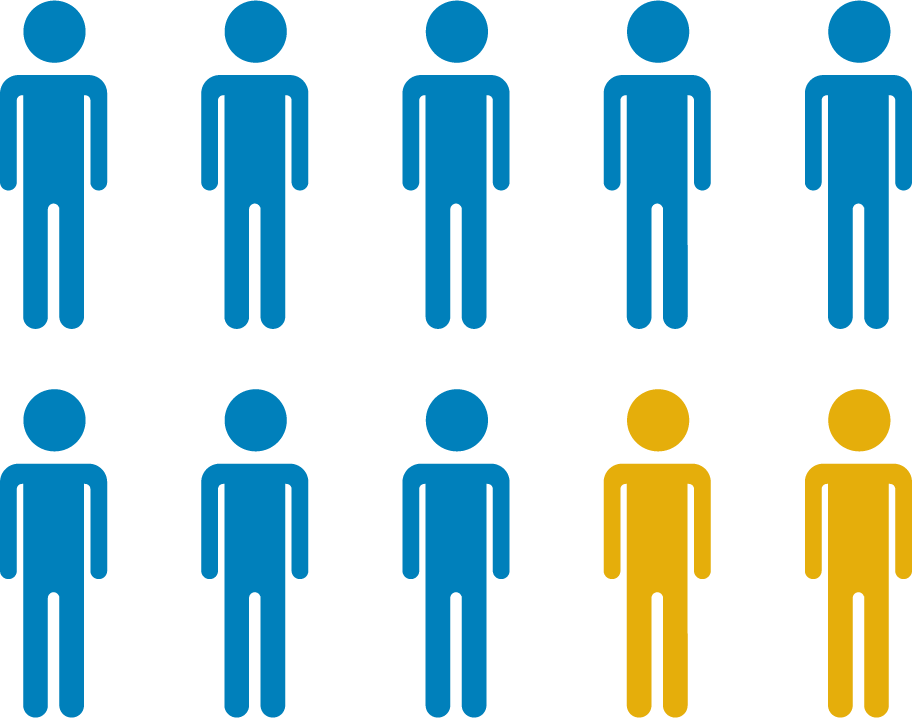

A new Reuters/Ipsos survey shares that most of us, 70 percent, are in favor of the single-payer system: 85 percent of Democrats and 52 percent of Republicans. Perhaps even more surprising is that a mere 20 percent of us actually dislike the concept.

Under this plan, we’d all be lumped into one communal pot, run by the government, and we’d no longer have to fret over those confounding deductibles and premiums. We’d experience improved benefits, he promises, such as dental, vision and hearing.

Major tax increases would fund the plan that includes the following:

- A 6.2 percent income-based health care premium paid by employers.

- A 2.2 percent income-based premium paid by households.

- Progressive income tax rates.

- Taxing capital gains and dividends the same as income from work.

- Limiting tax deductions for rich.

- Savings from health tax expenditures.

The government’s costs would increase to nearly $33 trillion during its first 10 years (2022 to 2031) says a “working paper”reportfrom Charles Blahous at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. That number assumes enactment this year.

Emory University health policy professor Kenneth Thorpe, who has also studied M4A, says annual costs to the federal government will average between $2.5 trillion to $3 trillion.

The idea of anything “for all” has enormous appeal, but wait just a minute, says The Atlantic. This whole idea of single-payer, “an indulgent fantasy,” evolved because Republicans sought to kill the Affordable Care Act (ACA), or Obamacare, but the party couldn’t unite around a coherent alternative. What then?

Democrats want to sweep away the complexity of our current health policy status quo, says the author Reihan Salam, who’s not all that optimistic. “All health reformers in America must confront the hospital sector.” The Blahous report says Medicare for All would slice hospital and physician payments by up to 40 percent which would significantly impact physicians and hospitals’ willingness and ability to care for Medicare patients (Medicare currently only covers 92% of costs).

Which “M” Word?

The word “Medicare” may, in fact, be misused when applied to a single-payer program, because, says Politico, Medicare isn’t single payer at all, but a “bewilderingly complex” system, “a massive public-private hybrid coverage scheme, funded mostly by taxes.“

Further, Medicare’s audience is specific: seniors who receive benefits when working-age people’s pay is taxed. We’re talking about greatly expanding the beneficiary pool here: “Paying for everyone’s health care that way would be a radically different proposition, and far more expensive.“

What we’re really talking about is Medicaid for All, suggests the National Review, which reminds us that “the devil really is in the details.” Medicaid is not free and is funded significantly by the Federal Government inversely related to each State’s per capita income and doctors dislike Medicaid with its low reimbursements, and consumers complain about long lines and treatment delays.

Sanders’ plan would say bye-bye to all private health insurance and would mean all abortions are free and that illegal aliens will get free health care courtesy of the taxpayer; things that many Americans will not tolerate.

Comparing Apples to Apples

Looking at the much bigger picture, proponents on the “yea” side of M4A say that its benefits far outweigh the risks. First and foremost, the entire population would have the opportunity to be healthier, since having access to health care improves health.

Currently, under the ACA, employers with 50 or more full-time employees must provide health insurance to all of them. For mega-corporations, that expenditure isn’t a huge ask, but smaller companies may find it a stretch. If the government funds health insurance, that then lightens the load for all companies that may find they can increase employee pay as a result — if they choose to do so, of course.

One point that seems to go “either way”: health care spending per capita. The United States spends nearly twice as much as other wealthy countries, topping out at $10,348 per person, according to 2016 numbers from Peterson-Kaiser. Compare that to the United Kingdom at

$4,192 and Japan at $4,519.

Given our expenditures, this is one tough pill to swallow: According to the latest report from The Commonwealth Fund, even though we spend more, “the U.S. population has poorer health than other countries” and is “failing to deliver indicated services reliably to all who could benefit.“

On the “nay” side of things, opponents cite those major tax hikes and longer waiting times to see a doctor, possibly extending into weeks and months. Add to that the elimination of innovations in the private sector that lead to breakthrough discoveries, all as a result of competition being removed from the medical technology playing field. Finally, funding all of this would require “shifting” funds from other priorities already deemed “urgent,” such as the nation’s infrastructure, those crumbling roads, and bridges now made more urgent due to the disastrous effects of climate change.

There’s no indication that this problem will be quickly solved, only that discussions will continue, while any momentum to effect positive change remains questionable. Americans would like to take the healthcare insurance coverage bull by the horns, but unfortunately, understand it’s just not within their power to do so. Until then, it’s a waiting game and may be for some time.