If you wanted to get control of your household spending, you’d set a budget and spend no more than it allowed. You might wonder why we don’t just do the same for spending on American health care.

Though government budgets are different from household budgets, the idea of putting a firm limit on health care spending is far from unknown. Many countries, including Canada, Switzerland and Britain, pay hospitals entirely or partly this way.

Under such a capped system, called global budgeting, a hospital has an incentive to deliver less care — including reducing hospital admissions — and to increase the efficiency of the care it does deliver.

Capping hospital spending raises concerns about harming quality and access. On these grounds, hospital executives and patient advocates might strongly resist spending constraints in the United States.

And yet some American hospitals and health systems already operate this way, including Kaiser Permanente and the Veterans Health Administration. To address concerns about access and quality, these programs are usually paired with quality monitoring and improvement initiatives.

That brings us to Maryland’s experience with a capped system. The evidence from the state is far from conclusive, but this is a weighty and much-watched experiment for health researchers, so it’s worth diving into the details of the latest studies.

Starting in 2010 with eight rural hospitals, and expanding its plan in 2014 to the state’s other hospitals, Maryland set global budgets for hospital inpatient and outpatient services, as well as emergency department care. Each hospital’s budget is based on its past revenue and encompasses all payers for care, including Medicare, Medicaid and commercial market insurance. Budgets for hospitals are updated every year to ensure that their spending grows more slowly than the state’s economy.

Because physician services are not part of the budgets, there is an incentive to provide more physician office visits, including primary care. According to some reports, Maryland hospitals are responding to this incentive by providing additional support outside their walls to patients who have chronic illnesses or who have recently been discharged from a hospital. Greater use of primary care by such patients, for example, could reduce the need for future hospital admissions.

In 2013, early results found, rural hospital admissions and readmissions were both down from their levels before the system was introduced.

In the first three years of the expanded program, revenue growth for Maryland’s hospitals stayed below the state-set cap of 3.58 percent, saving Medicare $586 million. Spending was lower on hospital outpatient services, including visits to the emergency department that do not lead to hospital admissions. In addition, preventable health conditions and mortality fell.

According to a new report from RTI, a nonprofit research organization, Maryland’s program did not reap savings for the privately insured population (even though inpatient admissions fell for that group). However, the study corroborated the impressive Medicare savings, driven by a drop in hospital admissions. In reaching these findings, the study compared Maryland’s hospitals with analogous ones in other states, which served as stand-ins for what would have happened to Maryland hospitals had global budgeting not been introduced.

But a recent study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, was decidedly less encouraging.

Led by Eric Roberts, a health economist with the University of Pittsburgh, the study examined how Maryland achieved its Medicare savings, using data from 2009-2015. Like RTI’s report, it also compared Maryland hospitals’ experience with that of comparable hospitals elsewhere.

However, unlike the RTI report, Mr. Roberts’s study did not find consistent evidence that changes in hospital use in Maryland could be attributed to global budgeting. His study also examined primary care use. Here, too, it did not find consistent evidence that Maryland differed from elsewhere. Because of the challenges of matching Maryland hospitals to others outside of the state for comparison, the authors took several statistical approaches in reaching their findings. With some approaches, the changes observed in Maryland were comparable to those in other states, raising uncertainty about their cause.

A separate study by the same authors published in Health Affairs analyzed the earlier global budget program for Maryland’s rural hospitals. They were able to use other Maryland hospitals as controls. Still, after three years, they did not find an impact of the program on hospital use or spending.

Changes brought about by the Affordable Care Act, which also passed in 2010, coincide with Maryland’s hospital payment reforms. The A.C.A. included many provisions aimed at reducing spending, and those changes could have led to hospital use and spending in other states on par with those seen in Maryland.

A limitation of Maryland’s approach is that payments to physicians are not included in its global budgets. “Maryland didn’t put the state’s health system on a budget — it only put hospitals on a budget,” said Ateev Mehrotra, the study’s senior author and an associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School. “Slowing health care spending and fostering better coordination requires including physicians who make the day-to-day decisions about how care is delivered.”

A broader global budget program for Maryland is in the works. The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is reviewing a state application that commits to global budgets for Medicare physician and hospital spending. An editorial that accompanied the JAMA Internal Medicine study noted that a few years may be insufficient time to detect changes. It suggests that five to 10 years may be more appropriate.

“Maryland hospitals are only beginning to capitalize on the model’s incentives to transform care in their communities,” said Joshua Sharfstein, a co-author of the editorial and a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “This means that as Maryland moves forward with new stages of innovation, there is a great deal more potential upside.” As former secretary of health and mental hygiene in Maryland, he helped institute the Maryland hospital payment approach.

Global budgets are unusual in the United States, but their intuitive appeal is growing. A California bill is calling for a commission that would set a global budget for the state. And soon Maryland won’t be the only state using such a system. Pennsylvania is planning a similar program for its rural hospitals.

Can this system work across America?

How much spending control is ceded to the government is the major battle line in health care politics. An approach like Maryland’s doesn’t just poke a toe over that line, it leaps miles beyond it.

But the United States has been trying to get a handle on health care costs for decades, spending far more than other advanced nations without necessarily getting better outcomes. A successful Maryland experiment could open an avenue to cut costs through the states, perhaps one state at a time, bypassing the steep political hurdle of selling a national plan.

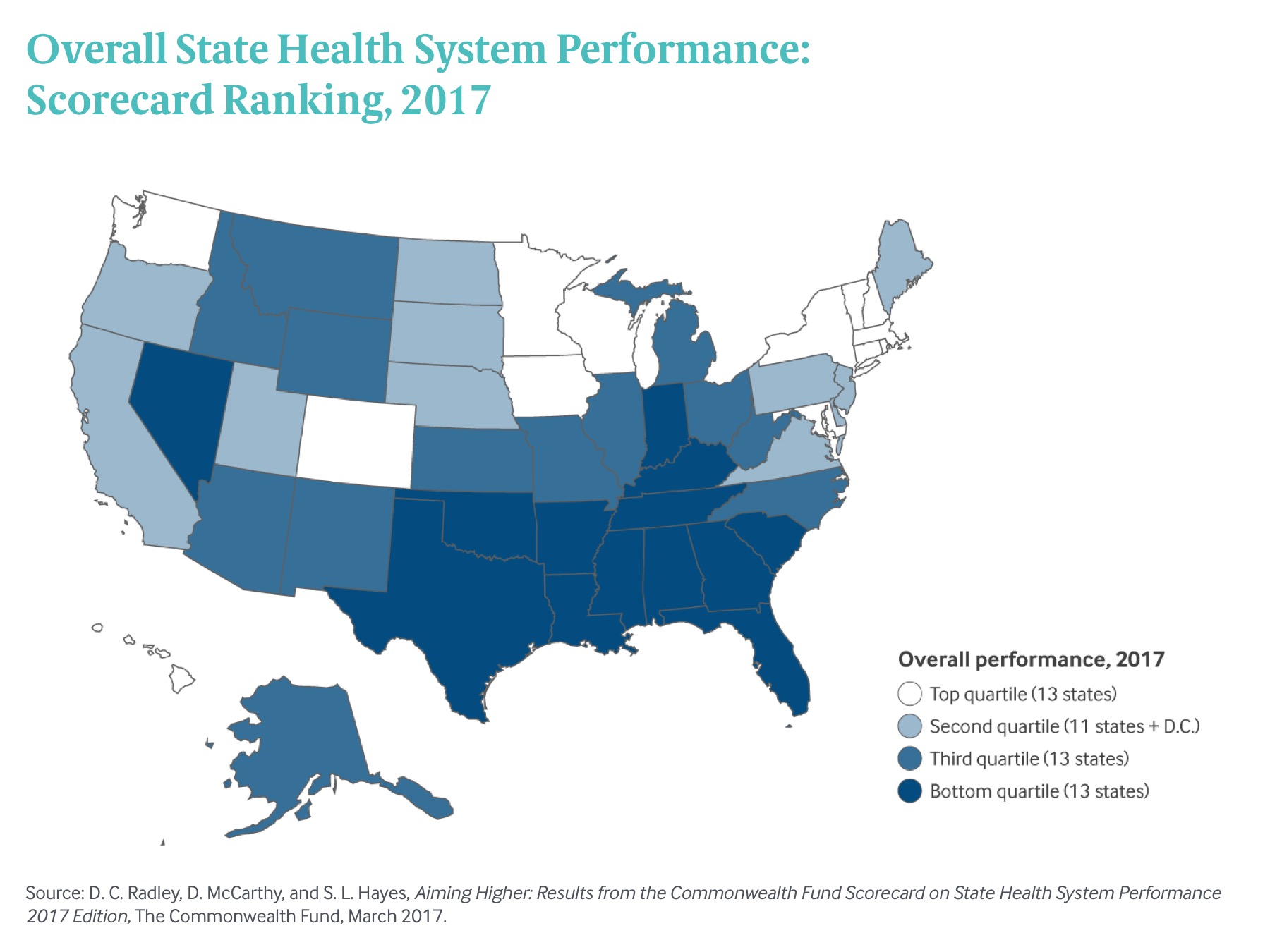

Exhibit 1: Overall State Health System Performance: Scorecard Ranking, 2017

Exhibit 1: Overall State Health System Performance: Scorecard Ranking, 2017