https://www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/healthpolicy/72001?pop=0&ba=1&xid=fb-md-pcp&trw=no

A reckoning is coming, outgoing BlueCross executive says.

A reckoning is coming to American healthcare, said Chester Burrell, outgoing CEO of the CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield health plan, here at the annual meeting of the National Hispanic Medical Association.

Burrell, speaking on Friday, told the audience there are five things physicians should worry about, “because they worry me”:

1. The effects of the recently passed tax bill. “If the full effect of this tax cut is experienced, then the federal debt will go above 100% of GDP [gross domestic product] and will become the highest it’s been since World War II,” said Burrell. That may be OK while the economy is strong, “but we’ve got a huge problem if it ever turns and goes back into recession mode,” he said. “This will stimulate higher interest rates, and higher interest rates will crowd out funding in the federal government for initiatives that are needed,” including those in healthcare.

Burrell noted that 74 million people are currently covered by Medicaid, 60 million by Medicare, and 10 million by the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), while another 10 million people are getting federally subsidized health insurance through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) insurance exchanges. “What happens when interest’s demand on federal revenue starts to crowd out future investment in these government programs that provide healthcare for tens of millions of Americans?”

2. The increasing obesity problem. “Thirty percent of the U.S. population is obese; 70% of the total population are either obese or overweight,” said Burrell. “There is an epidemic of diabetes, heart disease, and coronary artery disease coming from those demographics, and Baby Boomers will see these things in full flower in the next 10 years as they move fully into Medicare.”

3. The “congealing” of the U.S. healthcare system. This is occurring in two ways, Burrell said. First, “you’ll see large integrated delivery systems [being] built around academic medical centers — very good quality care [but] 50%-100% more expensive than the community average.”

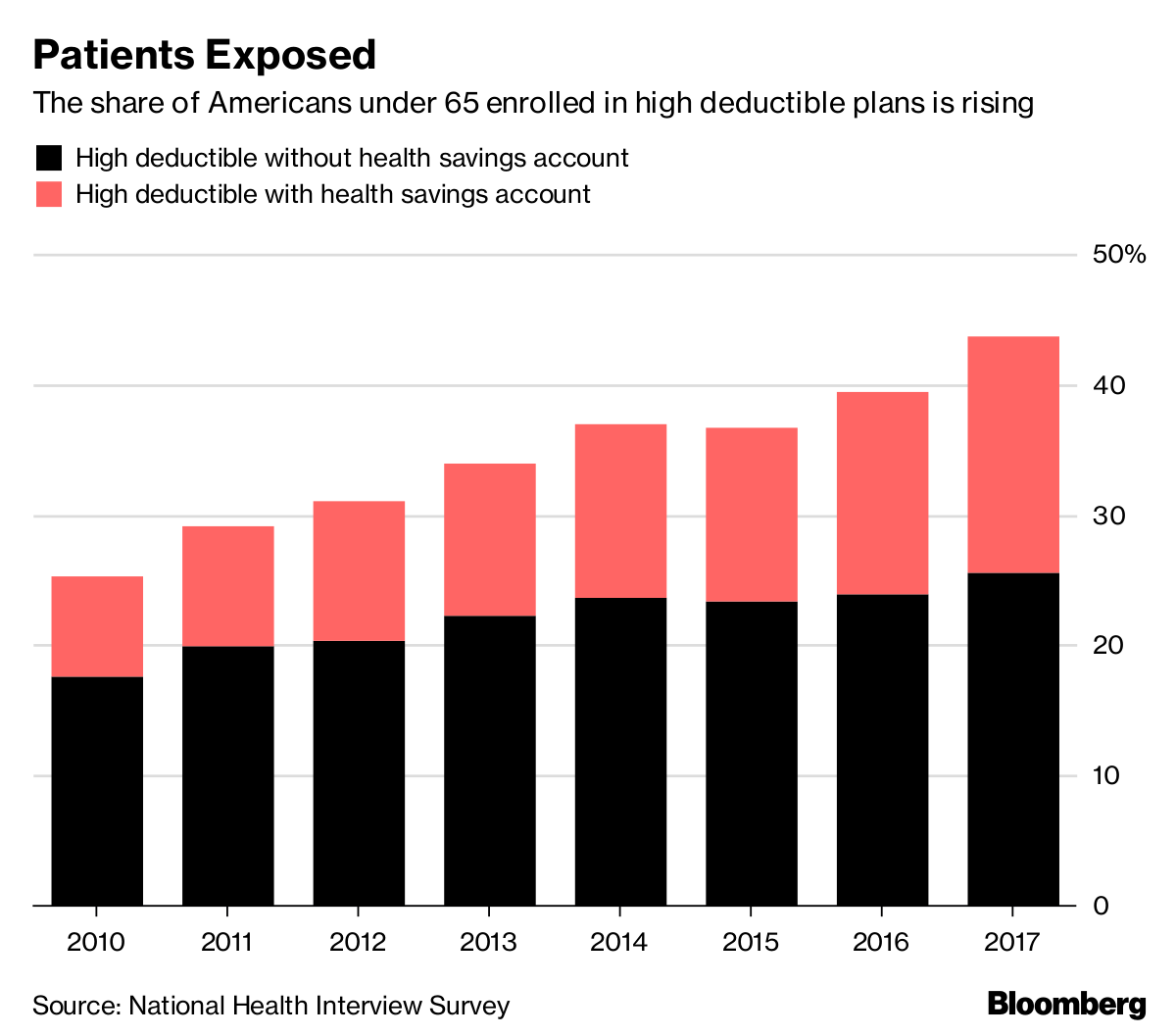

To see how this affects patients, take a family of four — a 40-year-old dad, 33-year-old mom, and two teenage kids — who are buying a health insurance policy from CareFirst via the ACA exchange, with no subsidy. “The cost for their premium and deductibles, copays, and coinsurance [would be] $33,000,” he said. But if all of the care were provided by academic medical centers? “$60,000,” he said. “What these big systems are doing is consolidating community hospitals and independent physician groups, and creating oligopolies.”

Another way the system is “congealing” is the emergence of specialty practices that are backed by private equity companies, said Burrell. “The largest urology group in our area was bought by a private equity firm. How do they make money? They increase fees. There is not an issue on quality but there is a profound issue on costs.”

4. The undermining of the private healthcare market. “Just recently, we have gotten rid of the individual mandate, and the [cost-sharing reduction] subsidies that were [expected to be] in the omnibus bill … were taken out of the bill,” he said. And state governments are now developing alternatives to the ACA such as short-term duration insurance policies — originally designed to last only 3 months but now being pushed up to a year, with the possibility of renewal — that don’t have to adhere to ACA coverage requirements, said Burrell.

5. The lackluster performance of new payment models. “Despite the innovation fostering under [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation] programs — the whole idea was to create a series of initiatives that might show the wave of the future — ACOs [accountable care organizations] and the like don’t show the promise intended for them, and there is no new model one could say is demonstrably more successful,” he said.

“So beware — there’s a reckoning coming,” Burrell said. “Maybe change occurs only when there is a rip-roaring crisis; we’re coming to it.” Part of the issue is cost: “As carbon dioxide is to global warming, cost is to healthcare. We deal with it every day … We face a future where cutbacks in funding could dramatically affect accessibility of care.”

“Does that mean we move to move single-payer, some major repositioning?” he said. “I don’t know, but in 35 years in this field, I’ve never experienced a time quite like this … Be vigilant, be involved, be committed to serving these populations.”