https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/finance/top-5-differences-between-nfps-and-profit-hospitals

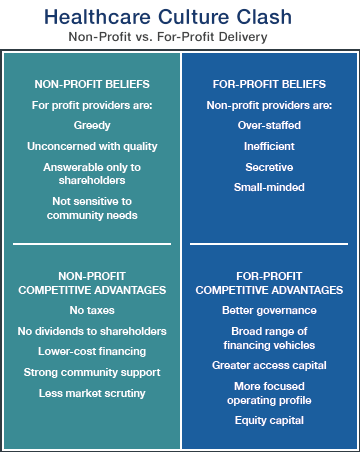

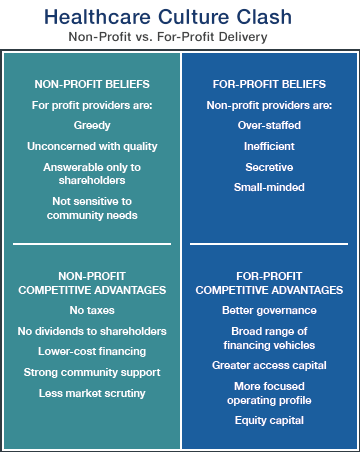

Although nonprofit and for-profit hospitals are fundamentally similar, there are significant cultural and operational differences, such as strategic approaches to scale and operational discipline.

All hospitals serve patients, employ physicians and nurses, and operate in tightly regulated frameworks for clinical services. For-profit hospitals add a unique element to the mix: generating return for investors.

This additional ingredient gives the organizational culture at for-profits a subtly but significantly different flavor than the atmosphere at their nonprofit counterparts, says Yvette Doran, chief operating officer at Saint Thomas Medical Partners in Nashville, TN.

“When I think of the differences, culture is at the top of my list. The culture at for-profits is business-driven. The culture at nonprofits is service-driven,” she says.

Doran says the differences between for-profits and nonprofits reflect cultural nuances rather than cultural divides. “Good hospitals need both. Without the business aspects on one hand, and the service aspects on the other, you can’t function well.”

There are five primary differences between for-profit and nonprofit hospitals.

1. Tax Status

The most obvious difference between nonprofit and for-profit hospitals is tax status, and it has a major impact financially on hospitals and the communities they serve.

Hospital payment of local and state taxes is a significant benefit for municipal and state governments, says Gary D. Willis, CPA, a former for-profit health system CFO who currently serves as CFO at Amedisys Inc., a home health, hospice, and personal care company in Baton Rouge, LA. The taxes that for-profit hospitals pay support “local schools, development of roads, recruitment of business and industry, and other needed services,” he says.

The financial burden of paying taxes influences corporate culture—emphasizing cost consciousness and operational discipline, says Andrew Slusser, senior vice president at Brentwood, TN-based RCCH Healthcare Partners.

“For-profit hospitals generally have to be more cost-efficient because of the financial hurdles they have to clear: sales taxes, property taxes, all the taxes nonprofits don’t have to worry about,” he says.

“One of the initiatives we’ve had success with—in both new and existing hospitals—is to conduct an Operations Assessment Team survey. It’s in essence a deep dive into all operational costs to see where efficiencies may have been missed before. We often discover we’re able to eliminate duplicative costs, stop doing work that’s no longer adding value, or in some cases actually do more with less,” Slusser says.

2. Operational Discipline

With positive financial performance among the primary goals of shareholders and the top executive leadership, operational discipline is one of the distinguishing characteristics of for-profit hospitals, says Neville Zar, senior vice president of revenue operations at Boston-based Steward Health Care System, a for-profit that includes 3,500 physicians and 18 hospital campuses in four states.

“At Steward, we believe we’ve done a good job establishing operational discipline. It means accountability. It means predictability. It means responsibility. It’s like hygiene. You wake up, brush your teeth, and this is part of what you do every day.”

A revenue-cycle dashboard report is circulated at Steward every Monday morning at 7 a.m., including point-of-service cash collections, patient coverage eligibility for government programs such as Medicaid, and productivity metrics, he says. “There’s predictability with that.”

A high level of accountability fuels operational discipline at Steward and other for-profits, Zar says.

There is no ignoring the financial numbers at Steward, which installed wide-screen TVs in most business offices four years ago to post financial performance information in real-time. “There are updates every 15 minutes. You can’t hide in your cube,” he says. “There was a 15% to 20% improvement in efficiency after those TVs went up.”

3. Financial Pressure

Accountability for financial performance flows from the top of for-profit health systems and hospitals, says Dick Escue, senior vice president and chief information officer at the Hawaii Medical Service Association in Honolulu.

Escue worked for many years at a rehabilitation services organization that for-profit Kindred Healthcare of Louisville, Kentucky, acquired in 2011. “We were a publicly traded company. At a high level, quarterly, our CEO and CFO were going to New York to report to analysts. You never want to go there and disappoint. … You’re not going to keep your job as the CEO or CFO of a publicly traded company if you produce results that disappoint.”

Finance team members at for-profits must be willing to push themselves to meet performance goals, Zar says.

“Steward is a very driven organization. It’s not 9-to-5 hours. Everybody in healthcare works hard, but we work really hard. We’re driven by each quarter, by each month. People will work the weekend at the end of the month or the end of the quarter to put in the extra hours to make sure we meet our targets. There’s a lot of focus on the financial results, from the senior executives to the worker bees. We’re not ashamed of it.”

“Cash blitzes” are one method Steward’s revenue cycle team uses to boost revenue when financial performance slips, he says. Based on information gathered during team meetings at the hospital level, the revenue cycle staff focuses a cash blitz on efforts that have a high likelihood of generating cash collections, including tackling high-balance accounts and addressing payment delays linked to claims processing such as clinical documentation queries from payers.

For-profit hospitals routinely utilize monetary incentives in the compensation packages of the C-Suite leadership, says Brian B. Sanderson, managing principal of healthcare services at Oak Brook, IL–based Crowe Horwath LLP.

“The compensation structures in the for-profits tend to be much more incentive-based than compensation at not-for-profits,” he says. “Senior executive compensation is tied to similar elements as found in other for-profit environments, including stock price and margin on operations.”

In contrast to offering generous incentives that reward robust financial performance, for-profits do not hesitate to cut costs in lean times, Escue says.

“The rigor around spending, whether it’s capital spending, operating spending, or payroll, is more intense at for-profits. The things that got cut when I worked in the back office of a for-profit were overhead. There was constant pressure to reduce overhead,” he says. “Contractors and consultants are let go, at least temporarily. Hiring is frozen, with budgeted openings going unfilled. Any other budgeted, but not committed, spending is frozen.”

4. Scale

The for-profit hospital sector is highly concentrated.

There are 4,862 community hospitals in the country, according to the American Hospital Association. Nongovernmental not-for-profit hospitals account for the largest number of facilities at 2,845. There are 1,034 for-profit hospitals, and 983 state and local government hospitals.

In 2016, the country’s for-profit hospital trade association, the Washington, DC–based Federation of American Hospitals, represented a dozen health systems that owned about 635 hospitals. Four of the FAH health systems accounted for about 520 hospitals: Franklin, TN-based Community Hospital Systems (CHS); Nashville-based Hospital Corporation of America; Brentwood, TN–based LifePoint Health; and Dallas-based Tenet Healthcare Corporation.

Scale generates several operational benefits at for-profit hospitals.

“Scale is critically important,” says Julie Soekoro, CFO at Grandview Medical Center, a CHS-owned, 372-bed hospital in Birmingham, Alabama. “What we benefit from at Grandview is access to resources and expertise. I really don’t use consultants at Grandview because we have corporate expertise for challenges like ICD-10 coding. That is a tremendous benefit.”

Grandview also benefits from the best practices that have been shared and standardized across the 146 CHS hospitals. “Best practices can have a direct impact on value,” Soekoro says. “The infrastructure is there. For-profits are well-positioned for the consolidated healthcare market of the future… You can add a lot of individual hospitals without having to add expertise at the corporate office.”

The High Reliability and Safety program at CHS is an example of how standardizing best practices across the health system’s hospitals has generated significant performance gains, she says.

“A few years ago, CHS embarked on a journey to institute a culture of high reliability at the hospitals. The hospitals and affiliated organizations have worked to establish safety as a ‘core value.’ At Grandview, we have hard-wired a number of initiatives, including daily safety huddles and multiple evidence-based, best-practice error prevention methods.”

Scale also plays a crucial role in one of the most significant advantages of for-profit hospitals relative to their nonprofit counterparts: access to capital.

Ready access to capital gives for-profits the ability to move faster than their nonprofit counterparts, Sanderson says. “They’re finding that their access to capital is a linchpin for them. … When a for-profit has better access to capital, it can make decisions rapidly and make investments rapidly. Many not-for-profits don’t have that luxury.”

5. Competitive Edge

There are valuable lessons for nonprofits to draw from the for-profit business model as the healthcare industry shifts from volume to value.

When healthcare providers negotiate managed care contracts, for-profits have a bargaining advantage over nonprofits, Doran says. “In managed care contracts, for profits look for leverage and nonprofits look for partnership opportunities. The appetite for aggressive negotiations is much more palatable among for-profits.”