Welcome to the “Lessons from the C-suite” series, featuring Advisory Board President Eric Larsen’s conversations with the most influential leaders in healthcare.

In this edition, Bill Gassen, President and CEO of Sanford Health and James Hereford, President and CEO of Fairview Health Services talk with Eric about the planned merger that will create the 11th largest health system in the United States that would span North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota.

The two CEOs describe the urgency and intent behind the merger, why not all disruptors are equally disruptive, and why it takes more than size to harness scale in healthcare.

Question: Bill and James, let’s jump right in. The two of you are architecting one of the most significant health system mergers of 2023 — a combination of Sanford Health and Fairview, which on its completion, will result in the 11th largest health system in the US. The discussions have attracted, understandably, a lot of interest and scrutiny not just in each of your communities, but nationally. Some may not be aware, but this is not the first time that Sanford and Fairview have considered coming together. Bill, let’s start with you – why is this time different?

Gassen: Eric, you’re right. This is not the only time our two organizations have considered the idea of merging. James and I, and our respective boards and organizations, have examined every element of the union and are confident that this is the right time to proceed. We have executed a Letter of Intent (LOI) and submitted an HSR filing that has been reviewed by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The parties provided substantial amounts of information to the FTC and the HSR process and it is now complete. There is an unwavering commitment from our respective leaders and our organizations to see this through.

It is a false choice for anyone to believe that James or I or anybody else has the benefit of sitting back and saying, well, maybe I’ll just maintain the world that I live in today. The healthcare status quo is gone. What is in front of us is taking the steps needed to ensure that we can continue to provide the best possible service for our patients, employees, and communities. Taking control over our destiny. We want to come together in a merger between our two organizations to put us in a position to fundamentally change and to be an agent for the modernization of the way care is delivered into the future. Our organizations exist only to serve patients, employees, and our communities. That is not up for debate. What we have in front of us is a decision to make that better for generations to come.

Hereford: I think Bill articulated that very well. Our purpose is to combine to improve and sustain our ability to offer world class healthcare. It is not simply a function of scale, you have to combine that with an intent to drive change, to improve value, and to innovate. And that’s a rare thing to have that intent. We have that intent today.

Avoiding the ‘Noah’s Ark’ problem

Q: Let’s go a bit deeper into the horizontal consolidation among health systems. This isn’t a new phenomenon — in fact, our $1.4 trillion hospital sector is already massively consolidated, with the top 100 systems controlling almost $900 billion in revenue. But with this degree of concentration, a lot of disillusionment: we just haven’t seen compelling or provable quality improvements, let alone the scale of cost reductions projected. Some of this might be what I call the “Noah’s Ark” problem—two of everything (two CEOs, two headquarters, two EHRs, etc.) … in other words, very little rationalization of back-office infrastructure or staffing.

I think about the proposed Sanford-Fairview merger differently. I might even characterize it as more a “vertical” merger, instead of “horizontal” — a combination of different and complementary capabilities instead of overlapping or competing ones — including Sanford’s proprietary health plan and virtual hospital investments, bringing Fairview’s specialty pharmacy and post-acute companies into the combination — for example. Am I thinking about this the right way?

Gassen: I think your characterization is right, Eric. We are different but very complementary organizations. We are contiguous as it relates to geography, but there is no overlap. We serve distinctly different populations in a similar part of the country. Roughly two-thirds of the patients who have been served today at Sanford Health come to us from a rural community. While most of those who Fairview serves come from much more densely populated urban communities. Both of those subsets of our population are experiencing similar challenges. There’s a need for financial sustainability, both on the provider side as well as on the patient side of the house.

When you think about our service mix, there are a number of complementary areas that make our union additive. Specialty and subspecialty expertise at Fairview coupled with a robust primary care backbone from Sanford plus our Virtual Care initiative and significant philanthropic investment will come together to create powerful healthcare solutions.

The fact that at Sanford alone we have $350 million solely dedicated to, and available for, scaling virtual care is amazing. And when you think about applying that investment to Sanford and Fairview, the opportunities are limitless. We’re going to be able to serve both our rural and urban communities, allowing us to truly transform the way in which healthcare is delivered and experienced in this part of the country.

And for those outside our orbit, they’ll say, “I want to partner with a combined Sanford Fairview” because that is much more attractive. And at the end of the day, partnering with us means that we’re all in a better position to transform the way in which we deliver care, how care is accessed, and how quality is improved. And do it in a financially sustainable way that allows us to deliver equitable care to more people in the upper Midwest.

Hereford: Here’s why scale matters: If you’re one hospital and you drive an innovation that requires a capital of investment of $1 million, that’s an expensive solution. But if you’ve got 100 hospitals, the size of that investment you made on a scale basis is much smaller. Therefore, your ability to drive the needed level of innovation is expanded significantly. To truly improve healthcare delivery, we must challenge ourselves to do things differently, but you have to have a certain level of scale to be able to do that.

Health system transformation must happen now

Q: I want to expand on the earlier point you made that the old health system status quo is forever gone. 2022, for health systems, was something of an Armageddon year — the worst on record with 11 out of 12 months with negative margins; supply chain costs up 17% versus pre-pandemic; health systems collectively spending an extra $125 billion on Labor last year compared to 2021. So not a great “state of the union” for acute-care centric health systems. How does this macroeconomic backdrop factor into your planning?

Hereford: Conceptually, cognitively, I would offer that hospital CEOs probably all know that the good old days are gone. But you don’t see organizations responding as if they’re gone. And we’re on the precipice of a significant cliff. The fundamental things that have defined healthcare and not-for-profit healthcare for decades have fundamentally shifted. We need to change in response.

We’re going to have 80,000 people when we combine. The challenge for us as leaders is going to be how do we shift the mindset and change the way we think about care delivery while maintaining essential services that persist with challenging economics. We are a high capital, low margin business that is critical to society.

Gassen: James, it’s as you and I talk about a lot. We don’t get the benefit of hitting pause, taking a year to revamp the industry because it’s 24 by 7 by 365. There are no breaks.

And while we’re doing that and while we are delivering essential services, the 45,000 incredible caregivers at Sanford and the 35,000 incredible caregivers at Fairview, collectively, are going to figure out how we evolve together as a unified organization to continue to elevate that critical work of patient care. And we don’t get reimbursed for a lot of those services. But those are essential services that people need.

If we want to be able to meet the needs of vulnerable patients and communities, we must face the increased pressure to lower costs and increase scale to drive positive margins. Those areas are few and far between in not-for-profit healthcare delivery. So, it necessitates that we continue to evolve and think differently about the work that we do driving down costs.

Larsen: And that’s increasingly becoming difficult — even for big players. I’ve been writing ruefully about the “billion-dollar club” — preeminent health systems like Ascension, MGB and Cleveland Clinic each posting more than a billion dollars in total losses (and even more in some cases, e.g., $4.5 billion for Kaiser). But Sanford, in contrast, is one of just a small handful of health systems that somehow managed to end 2022 in the black, with a $188 million operating income last year. Bill, any reflections on how you and the team did that?

Gassen: We count ourselves very, very blessed to be among the few who had the opportunity to experience positive margins in 2022. I would give first and foremost credit to an exceptionally talented team inside and outside the organization. They do a wonderful job of focusing their attention on that which matters most, which is patient care.

It’s also a very well-constructed organization from the ground up. We benefit coming into both the pandemic and then through the financial headwinds in 2022 with a well-diversified set of assets and geographies. On the acute side it’s largely contained across Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota.

In Minnesota, and across those above geographies, we have a great complement of assets across our provider sponsored health plan, hospitals, clinics, post-acute care, as well as our research enterprise, all of which, collectively, allowed us to do a better job than some of our peers at weathering that “economic storm” you mentioned earlier.

But, most importantly, it’s just the time that we’ve had to mature as an organization. And with that time, we’ve integrated more deeply as one singular operating company. Sanford Health is not a holding company. The decisions that we make, we make as one singular integrated system and that is a part of that special sauce that’s allowed us to be successful.

Everything that I’ve described has just given us a little bit of a head start and now it’s incumbent upon us to maximize that time.

The imagined and real disruption in healthcare

Q: Bill, you mentioned time is of the essence. And so far, we’ve mostly localized our discussion today talking about health system-specific competitive issues, which makes sense. But it also makes sense to lift up and survey the healthcare ecosystem outside of health systems and note the fact that even when Sanford and Fairview combine and represent $14 billion in revenue, it will still be comparatively tiny to some of the non-traditional players seeking to disrupt healthcare. We have trillion-dollar market cap companies like Amazon investing aggressively into the primary care, pharmacy, and home enablement spaces. We have Fortune 10 companies like UnitedHealth Group and CVS-Aetna vertically integrating and building out sophisticated ambulatory delivery systems. And we have retailers like Walmart and Best Buy transitioning into parts of the healthcare delivery chain as well. So, while Sanford-Fairview will be sizable by most conventional healthcare metrics, it has some pretty formidable competition. How do you assess the new competitive landscape emerging?

Hereford: So, I thought a lot about this because I do think it’s one of the most significant aspects of our industry right now. The opportunity for a CVS-Aetna is that they are proximate to a lot of people in the US. And there’s a lot of things that they could do for patients with a simple presentation of acute symptoms or for fairly simple chronic disease and stabilization. But that is not what drives the cost of health care in the US. It’s when people get very sick.

People receiving specialist care in hospitals are having complex procedures. They’re being treated for complex cancers. And we’re doing an amazing job of advancing the science and the technologies that we can apply to that. But that doesn’t happen in a drug store. That does not happen in a store front primary care office. That happens in organizations like ours. Our challenge is to create the same level of convenience, the same level of access, or partner in a smart way to achieve that.

Our job is to think about total cost of care within the context of delivering very complex care. That isn’t simply a function of primary care and that, I think, is our fundamental challenge. We can translate that into real total cost of care savings.

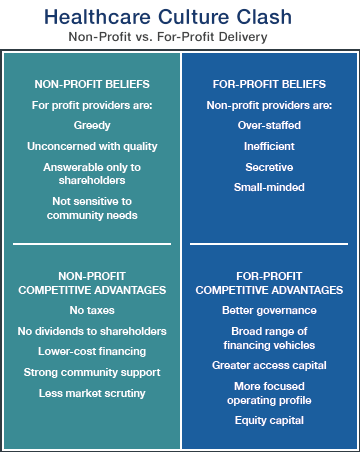

Gassen: For James and me, in our respective roles and responsibilities, this is our incredibly rewarding and incredibly difficult work. Because those other organizations aren’t required to provide care to everyone. They’re not required to provide free care. They’re not required to be able to provide services for which there is no margin. We don’t get to cherry pick.

It’s our responsibility to really be all things from a healthcare delivery perspective to all people, which means that we are always going to be challenged with how we do that in a financially sustainable way. I think it’s the beauty of where we find ourselves as an industry because out of that necessity comes that innovation that we’ve been talking about here because we can’t continue at current course and speed.

Larsen: When we start to talk about giants in healthcare we tend to index on their size and market cap and, as a result, we lump vertically integrating players and technology companies under the same umbrella. I think that’s a mistake. You have focused healthcare payers like CVS Aetna and UHG that are combining their underwriting business (and ownership of the premium dollar) with an ambulatory delivery network, with an emphasis on home and virtual care. To me that’s a very real and consequential development – and very different from what Big Tech is aspiring to do in our space.

Hereford: Eric, I agree.The world is so clearly changing and that is where the market and a number of very large healthcare organizations are betting. I do think that people who see the overall size of the healthcare marketplace and say “we want to be a part of that” but without any clear way of making sustainable margins.

Gassen: In contrast with the large public companies, as a not-profit health care system, it’s a fact of life that we operate on thin margins. But there are a lot of dollars floating around for other players in the healthcare ecosystem. Which to your point, is why people get enticed to enter into the healthcare space. Our goal with the transaction is to remain financially solid, with the resources needed to invest in our communities, while staying true to our non-profit mission.

Larsen: Your comments, Bill, underscore the power of being a ‘payvider’ in healthcare, which of course Sanford is. You’re in rarefied company — only a dozen or so health systems can claim this, and they have one thing in common — a very mature health plan function (average age of 44 years). So Intermountain, Geisinger, Kaiser, Sentara, Sanford and a small handful of others fit this bill. I presume a major part of the envisioned benefit of the merger is extending Sanford Health plan into Fairview. Can I get you both to comment on that?

Gassen: I certainly agree with you Eric about the importance of being a “payvider.” And of course, I’d also say there is a scale component to that, too. Today our health plan only has 220,000 covered lives. But it is a very valuable and strategic component of the larger Sanford Health system.

As we come together with Fairview into a combined system, we now have the opportunity to bring the Sanford Health plan and its additional options and opportunities for members to a much larger community. And one that’s backed by a combined system. It offers greater choices for the two million people across North Dakota, South Dakota, and Western Minnesota.

When we do that, it puts us in the best possible position to coordinate care that allows for the best outcomes, and as a consequence, also results in a better financial position for us. And so, when we think ahead to the opportunity to now apply the infrastructure that we’ve built to the greater Twin Cities market and beyond to bring that together with the care delivery assets and expertise of Fairview Health Services, we get really excited about the opportunities we unlock not just for the combined organization, but for importantly, for all the members within that community.

Healthcare’s technology paradox

Q: The above commentary on scaling out to wider geographies and connecting and transforming care brings me to the paradox of digital health. One of the only bright lights to come out of the pandemic was what I would characterize as a “Renaissance moment” in digital health — unprecedented funding ($72 billion globally in 2021 alone) fueling the creation of almost 13,000 digital startups, spanning new diagnostics, therapeutics, clinical/non-clinical workflow, care augmentation, you name it. And while we’re now seeing a rough contraction, with lots of companies starved for capital and struggling to sell into healthcare incumbents, we are going to see some winners and some transformational platforms emerge.

The question is, will healthcare incumbents like health systems be able to take advantage of this? The data are sobering — it takes an estimated 23 months for a health system to deploy a digital health technology (once it signs a contract). And while technology tends to be deflationary — lowers costs as it augments productivity — that just hasn’t happened in healthcare, as costs inexorably keep going up. How will the combined Sanford-Fairview tackle this? Who wants to go first?

Hereford: Let me start because I want to respond to something you said, Eric. You’re right, technology has been deflationary in other sectors but only since about 1995. In the 1990s many books in that period were asking “why are we investing all this money in technology across all sectors and we’re not seeing productivity improvements?”

But out of that question came reengineering — where companies started to reconfigure processes and workflows as opposed to just applying technologies. Only then did they see the deflationary benefits of greater efficiencies from technologies. So, I think that has a lot to do with how we’ve applied technology. We’ve had federal stimulus to apply technology, but it’s to apply technology for its own sake. Not to challenge how we use technology to make it easier to be a doctor or nurse. How do we use technology to make people more effective and therefore more efficient?

Gassen: I think that change, especially fundamental shifts, and changes to a business won’t happen until you absolutely have to. And that’s human nature.

The challenge ahead of us is to interrogate how we as an industry interact with our patients and ask, “How can we fundamentally tear that down to the studs and rebuild it better and fit for today?”

But I also want to be clear about why we’re here as a health system. Our reality is that there is a patient at the end of every single decision that we make. So, we must be extremely careful about how we look at processes and implement change. We know they’re rarely perfect, but oftentimes we do deliver the best outcome for the patient. Our job is to be able to make the right change without causing harm.

Larsen: Bill, we’ve made the argument together in past conversations that this same creation moment for digital health solutions beautifully aligns to address the conventional disadvantages of American rural medicine: insufficient infrastructure (hospitals, surgery centers, etc.) and a scarcity of clinicians and non-clinicians for the workforce. Digital health holds the promise to turn those deficits into advantages. And, you know, Sanford’s been a pioneer in launching a $350 million virtual hospital. Perhaps you can unpack this.

Gassen: I’d say our work here really has its origins in the unwavering belief that one zip code should not determine the level of care that a person receives. Every patient has the right to access world class care. So, it’s incumbent upon us, those of us who find ourselves in the privileged position to be in leadership in healthcare delivery organizations like Sanford and Fairview, to take the necessary steps to deploy the appropriate resources and to find the right partners to ensure that whether you’re living in the most rural parts of the heartland or an urban center, you get the best quality care possible.

We take great pride in the fact that our organization was built on the belief that we know many of our patients choose to live in rural America. Two-thirds of the patients today at Sanford Health, whom we have the privilege of serving, come to us from rural America.

It’s with that front and center, the Virtual Care initiative at Sanford Health is allowing us the opportunity to deliver world class care. It’s about making certain that through basically all facets of digital transformation, we leverage our resources to extend excellence in primary care, in specialty and subspecialty care, and offer those individuals access to that care close to home.

The vision for us is to ensure that those who choose to live in rural America are not forced to sacrifice access to high quality, dependable care. That’s at the core of both our beliefs and actions.

Larsen: And James, I think you’ve been one of the most progressive CEOs in the industry on thinking about capitalizing on digital health, innovation and partnering with capital allocators. And we talked about a few of them — leading VCs like Thrive or SignalFire who are partnering broadly with health systems — and finding ways to shorten the innovation cycle.

Hereford: It comes back to intent and purpose. Our job is to make sure that everybody can access high quality care and so the opportunity is to really think about the commonalities and leverage that across both rural America, urban communities, suburbs, exurbs, etc. The other thing that I think is often overlooked in your Cambrian explosion is the volume of scientific advancements over the last two decades.

I love the hypothetical of a medical student who learned everything about medicine in 1950 and how fast the volume of clinical knowledge would have doubled then. They would have had about 50 years before the knowledge base doubled. Today, an amazing medical student with the ambition to learn the entire body of clinical knowledge would have about seven months to see it doubled. That’s how fast medicine is advancing.

We built this industry based on highly specialized, incredibly smart, incredibly committed people who can master these topics. This volume of information on clinical care theory, the body of knowledge on clinical application, all layered on to how the business of care works is cognitive overload. We have got to give them better tools. We have got to help support them. I think we’re in a unique place to be able to really do something about it and create real solutions for people.

Gassen: Where we’re at right now necessitates that. And again, thinking a level deeper as it relates to rural America, the opportunity is so incredibly ripe because it’s necessary. The only way that we’re going to be able to scale to the level we need is to leverage and maximize technology. And so therein creates that opportunity and that necessity makes us a very fertile ground for organizations to come in and partner with us, to be able to extend those services.

The current deal’s state of play

Q: So, we started our conversation about the merger and went broad to talk about industry trends and the wider landscape. But I do want to circle back to a couple of the outstanding specifics of the merger. Sanford and Fairview are merging. What will the University of Minnesota’s relationship be with the merged organization?

Gassen: Both James and I firmly believe, and have articulated in our conversation with you today, the virtues of bringing Sanford Health and Fairview Health services together are absolutely essential to ensuring the delivery of world class healthcare in the upper Midwest. And we are committed to creating the right relationship with the University of Minnesota for it to pursue its mission.

Hereford: We’ve always said that we wanted the University to be part of what we’re building. And, the University of Minnesota has indicated their desire to purchase the academic assets of the system and we stand ready to engage with them to support that. If that is the path that they pursue and can get state funding to support, then we can work with them to determine the nature of the relationship between the new system and the University of Minnesota.

Larsen: And how about the other partners and players in the landscape? I’m thinking of the Minnesota Attorney General, the FTC, etc.

Gassen: We’ve engaged the elected officials across the states of North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota, and we’ve continued to keep them apprised. We’ve also worked very closely with regulators and are happy to report that following its review, the Federal Trade Commission cleared the transaction and the HSR process is complete.

At this point in time, we are working closely with Attorney General Keith Ellison’s office in the state of Minnesota to ensure that he has sufficient information to complete his analysis under antitrust and charities laws to ensure that he’s continuing to protect the interests of all Minnesotans. We remain very engaged and look forward to the conclusion of that work.

The future focus of leadership

Q: Ok, I’d like to round out this conversation with a look to the future. Can you foreshadow your division of labor…where you will be converging and where will you be dividing and conquering as CEOs?

Hereford: One of the great positives of this deal and one of the great signals of the quality of the rationale here is that Bill and I went into this with the question: How do we set this up to be successful over the long term?

You may have noticed Bill and I are different ages. Bill has a lot more runway than I have, so it was not a difficult decision on my part to say “look, it’s important for me to help with the transition because it’s a big deal, right? And it’s not going to be over in a year.” But I can be that bridging function to help support the transition. This is a long-term play and Bill’s the person who’s going to be able to be in the seat to really see that through.

And given my interests I can take on the innovation that we’re talking about and how we make the membrane of this organization a little more permeable and a little bit more friendly to partners, while also being very demanding of partners in terms of the value they create, and we create within the system.

I’m really excited about the opportunity to do that. I do think the way that we have approached this is a very enlightened approach.

Gassen: Standing on the shoulders of James’ comments, one of the many aspects that makes this merger unique is the collegiality and foresight from our respective boards that see how incredibly valuable it is to be able to have co-CEOs working together, focusing first and foremost on ensuring that we’re bringing together the two organizations as one integrated, transformative healthcare delivery organization. I think James and I get up every morning with the goal of making sure that that happens every single day.

And it’s not just that James will work on the innovation piece because it brings him joy and energy but also, it’s where he has a deep level of experience and expertise. I get to focus more of my time and energy on the day-to-day of the two organizations coming together.

Together, James and I will be able to jointly balance the combination of the two organizations with day-to-day delivery and the transformative opportunities for us because of the unique nature of our backgrounds and expertise.

Hereford: And I think that’s a real advantage for the organization. I’m sure there are going be times when I’ll say “Bill, we’ve got to change. You’ve got to do this”. And he’s going to say “yeah, but I can’t do that. I can’t make that kind of change.”

But that’s the kind of dialogue that this structure sets up for us to hold that tension productively as opposed to responding to the tyranny of the urgent, which is ever present in a large health care delivery system. Transformation of care delivery systems will require the ability to manage those competing dynamics. I really appreciate both the structure but also how Bill is approaching this.

Gassen: I do think that what we just described here will prove to be one of the finer distinguishing factors that allows us to really be successful. Because you do oftentimes find yourself with a choice between A or B. And for us we get to choose C — “all of the above” — and go forward and do that.