New outbreaks used to be traced back to crowded factories and rowdy bars. But now, the virus is so widespread not even health officials are able to keep up.

When the coronavirus first erupted in Sioux Falls, S.D., in the spring, Mayor Paul TenHaken arrived at work each morning with a clear mission: Stop the outbreak at the pork plant. Hundreds of employees, chopping meat shoulder to shoulder, had gotten sick in what was then the largest virus cluster in the United States.

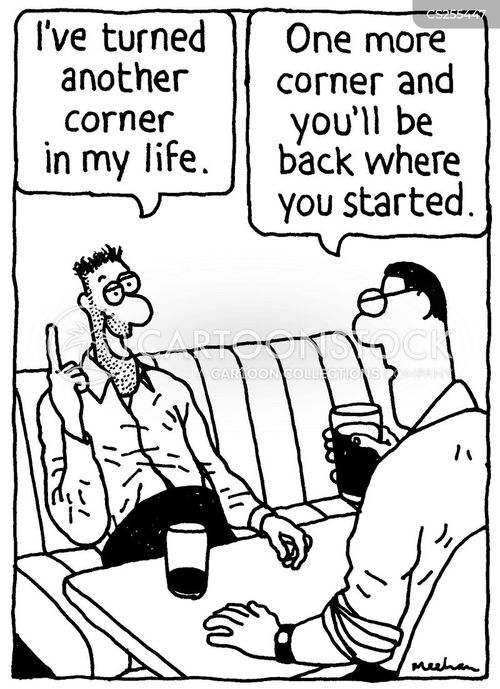

That outbreak was extinguished months ago, and these days, when he heads into City Hall, the situation is far more nebulous. The virus has spread all over town.

“You can swing a cat and hit someone who has got it,” said Mr. TenHaken, who had to reschedule his own meetings to Zoom this past week after his assistant tested positive for the virus.

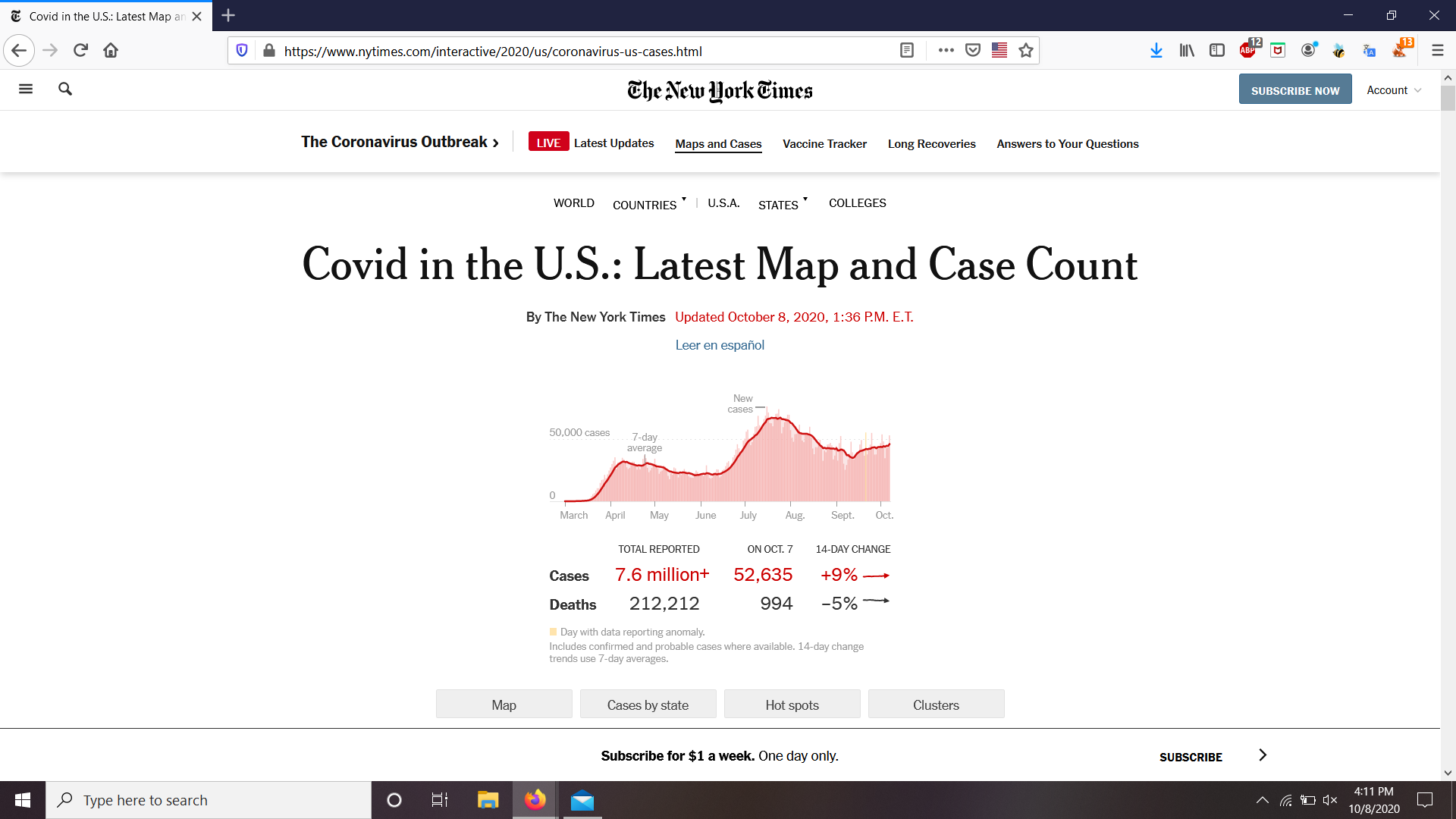

As the coronavirus soars across the country, charting a single-day record of 99,155 new cases on Friday and surpassing nine million cases nationwide, tracing the path of the pandemic in the United States is no longer simply challenging. It has become nearly impossible.

Gone are the days when Americans could easily understand the virus by tracking rising case numbers back to discrete sources — the crowded factory, the troubled nursing home, the rowdy bar. Now, there are so many cases, in so many places, that many people are coming to a frightening conclusion: They have no idea where the virus is spreading.

“It’s just kind of everywhere,” said Crystal Watson, a senior scholar at the Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who estimated that tracing coronavirus cases becomes difficult once the virus spreads to more than 10 cases per 100,000 people.

- The election. And its impact on you.

In some of the hardest-hit spots in the United States, the virus is spreading at 10 to 20 times that rate, and even health officials have all but given up trying to figure out who is giving the virus to whom.

There have been periods earlier in the pandemic when infections spread beyond large, well-understood clusters in prisons, business meetings and dinner parties, tearing through communities in ways that were nearly impossible to keep track of. But for the most part, that experience was isolated to hard-hit places like New York City in the spring and portions of the Sun Belt in the summer.

This time, the diffuse, chaotic spread is happening in many places at once. Infections are rising in 41 states, the country is recording an average of more than 79,000 new cases each day, and more Americans say they feel left to do their own lonely detective work.

“I was so careful,” said Denny Taylor, 45, who said he had taken exacting precautions — wearing a mask, getting groceries delivered — before he became the first in his family and among his co-workers to test positive for the virus. Lying in a hospital bed in Omaha this past week, he said he still had no idea where he caught it.

Uncovering the path of transmission from person to person, known as contact tracing, is seen as a key tool for containing the spread of the coronavirus. Within a day or two of testing positive, residents in many communities can expect to get a phone call from a trained contact tracer, who conducts a detailed interview before beginning the painstaking process of tracking down each new person who may have been exposed.

“We were pretty successful and we were very proud of how the case numbers went down,” said Dr. Sehyo Yune, who supervised a team of contact tracers in Massachusetts this spring. It was one of several strategies that helped tamp down earlier outbreaks in places like Massachusetts, New York and Washington, D.C.

But as cases skyrocket again in many states, many health officials have conceded that interviewing patients and dutifully calling each contact will not be enough to slow the outbreak. “Contact tracing is not going to save us,” said Dr. Ogechika Alozie, chief medical officer at Del Sol Medical Center in El Paso, where hospitalizations in the county have soared by more than 400 percent and officials issued a new order for residents to stay at home.

The problem, of course, is that failing to fully track the virus makes it much harder to get a sense of where the virus is flourishing, and how to get ahead of new outbreaks. But once an area spins out of control, trying to trace back each chain of transmission can feel like scooping cupfuls of water from a flood.

In some places, overwhelmed health officials have abandoned any pretense of keeping up.

In North Dakota, state officials announced they could no longer have one-on-one conversations with everyone who may have been exposed. Aside from situations involving schools and health care facilities, people who test positive were advised to notify their own contacts, leaving residents largely on their own to follow the trail of the outbreak.

In Philadelphia, where cases recently spiked to more than 300 per day, city officials acknowledged that they now must leave some cases untracked. Most people, they said, are catching the virus through family and friends.

“We weren’t supposed to get to this point,” said Dr. Arnold S. Monto, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan, who said the process of tracking cases and notifying people who may have been exposed is a gold standard of disease prevention but impractical after a certain level of infection.

“If you have five clusters going on at the same time,” he said, “it’s hard to say where it came from.”

When a first major outbreak hit Grand Forks, N.D., in April, the problem was clear: More than 150 employees of a wind turbine blade factory were infected. The factory shut its doors for several weeks, and public health officials tested and contact traced each case.

For the rest of the summer, Grand Forks, a college town of 56,000 on the border with Minnesota, saw almost no new infections. An uptick in August was quickly tied to students at the University of North Dakota and largely contained.

Now, though, any sense of control has vanished. Active cases of Covid-19 have quadrupled since the beginning of October to 912 in Grand Forks County, and about half the people contacted by the health department say they are not sure how they became infected.

“People are realizing that you can get it anywhere,” said Kailee Leingang, a 21-year-old nursing student who also works as a state contact tracer in Grand Forks. Even Ms. Leingang has fallen ill, along with several of her colleagues. She traces her case to her parents, who first started showing symptoms. Beyond that, the trail goes cold.

“They have no idea,” she said of where her parents came in contact with the virus.

Ms. Leingang, isolating at her home with her cat, feels sicker by the day. Dishes have piled up in the sink — she is too weak to stand long enough to wash them. But she is still working, calling at least 50 people a day to notify them that their tests came back positive, though her job is no longer to track who else they may have infected. “With the high number of cases right now,” she said, “our team can’t afford to have somebody not work.”

In earlier, quieter periods of the pandemic, the virus spread with some degree of certainty. In all but the hardest-hit cities, people could ask a common question — “Where did you get it?” — and often find tangible answers.

A popular college bar in East Lansing, Mich., Harper’s Restaurant and Brewpub, became a hot spot this summer after dozens of people piled into the bar, drinking, dancing and crowding close together. At least 192 people — 146 people at the bar and 46 people with ties to those at the bar — were infected. Afterward, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer shut down indoor dining in bars in parts of the state.

In Ingham County, which includes much of East Lansing, it is far harder to tell where the virus is spreading now. Of the county’s 4,700 reported cases over the course of the pandemic, more than 2,700 have come since the beginning of September.

Much of the new spread may be tied to students at Michigan State University, where students are living off campus and taking classes online. But every day, employers and residents call the Health Department to report random cases that defy easy explanation.

“It’s just a hodgepodge,” said Linda Vail, the Ingham County health officer.

Heidi Stevens is among the newly infected who considers her case a mystery. As a columnist at The Chicago Tribune, Ms. Stevens works from home. Her children attend school online. She wears a mask when she goes for a run, and she has not had a haircut since January.

So when she got a precautionary test a few weeks ago, with the hopes of inviting friends over to have cake for her daughter’s 15th birthday, Ms. Stevens was shocked to learn she was positive.

“I would drive myself crazy if I tried to really nail it down,” said Ms. Stevens, 46, who was hospitalized for three days and still wakes up with headaches. Did she pick up an infected apple at the grocery store and somehow touch her eye? Should she have been wearing a face shield, in addition to her mask? The possibilities feel endless.

“It’s just out there,” she said.