Cartoon – State of the Union on Covid Denial

https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/01/08/capitol-coronavirus/

Wednesday’s storming of the U.S. Capitol did not just overshadow one of the deadliest days of the coronavirus pandemic — it could have contributed to the crisis as a textbook potential superspreader, health experts warn.

Thousands of Trump supporters dismissive of the virus’s threat packed together with few face coverings — shouting, jostling and forcing their way indoors to halt certification of the election results, many converging from out of town at the president’s urging. Police rushed members of Congress to crowded quarters where legislators say some of their colleagues refused to wear masks as well.

“This was in so many ways an extraordinarily dangerous event yesterday, not only from the security aspects but from the public health aspects, and there will be a fair amount of disease that comes from it,” said Eric Toner, senior scholar at the John Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Experts said that resulting infections will be near-impossible to track, with massive crowds fanning out around the country and few rioters detained and identified. They also wondered if even a significant number of cases would register in a nation overwhelmed by the coronavirus. As Americans shared their shock and anger at the Capitol breach Thursday, the United States reported more than 132,000 people hospitalized with the virus, and more than 4,000 deaths from covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus — making it the highest single-day tally yet.

“It is a very real possibility that this will lead to a major outbreak but one that we may or may not be able to recognize,” Toner said. “All the cases to likely derive from this event will likely be lost in the huge number of cases we have in the country right now.”

Trump devotees who flocked to the capital this week said they were unconcerned by the virus, belittling common precautions known to slow its spread and echoing the president’s dismissive attitude toward rising case counts. Trump had encouraged them to gather in defiance of his election loss: “Big protest in D.C. on January 6th,” he tweeted last month. “Be there, will be wild!”

Mike Hebert, 73, drove two days from Kansas to participate. Marching toward the Capitol on Wednesday with an American flag, he said he did not feel the need to wear a face covering.

“I am as scared of the virus as I am of a butterfly,” said Hebert, adding that he is a veteran who was shot twice in Vietnam.

Sisters Courtney and Haley Stone left New York at 11 p.m. to make it to the Capitol by morning so they could quietly counterprotest, draped in Biden gear. “Do you want a mask? I have one,” Haley, 22, asked a Trump supporter, only to be rebuffed.

“Oh, you believe in the mask hoax?” the woman replied.

Health experts predicted Wednesday’s events will contribute to an ongoing case surge in the greater Washington region. The average number of daily new infections in Virginia, Maryland and the District of Columbia reached a record high Thursday, and current covid-19 hospitalizations in the District have risen 19 percent in the past week.

They also noted differences with other large gatherings such as Black Lives Matter protests. Fewer people wore masks during the Capitol protests and riot, they said, and crowds were indoors.

“If you wanted to organize an event to maximize the spread of covid it would be difficult to find one better than the one we witnessed yesterday,” said Jonathan Fielding, a professor at the schools of Public Health and Medicine at UCLA.

“You have the drivers of spreading at a time when we are bearing the heaviest burden of this terrible virus and terrible pandemic,” he said.

Calling in to CBS News Wednesday, Rep. Susan Wild (D-Pa.) described her evacuation to a “crowded” undisclosed location with 300 to 400 other people.

“It’s what I would call a covid superspreader event,” she said. “About half the people in the room are not wearing masks, even though they’ve been offered surgical masks. They’ve refused to wear them.”

She did not identify the lawmakers forgoing face coverings beyond saying they were Republicans, including some freshmen. The Committee on House Administration says it is a “critical necessity” to mask up while indoors at the Capitol, and D.C. has a strict mask mandate.

“It’s certainly exactly the kind of situation that we’ve been told by the medical doctors not to be in,” Wild said.

“We weren’t even allowed to get together with our families for Thanksgiving and Christmas,” she said, “and now we’re in a room with people who are flaunting the rules.”

At least one member of Congress has tested positive since the mob spurred an hours-long lockdown. Newly elected Rep. Jacob LaTurner (R-Kan.) tested positive for the coronavirus late Wednesday evening, according to a statement posted on his Twitter account. It said he is not experiencing symptoms.

“LaTurner is following the advice of the House physician and CDC guidelines and, therefore, does not plan to return to the House floor for votes until he is cleared to do so,” the statement said.

Luke Letlow, a 41-year-old congressman-elect from Louisiana, died of covid-19 last month.

Any infections among members of Congress and their staff will be far easier to contact-trace than those among rioters, said Angela Rasmussen, an affiliate at the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University.

“It certainly would have been easier if they were detained by Capitol police and identified, but testing suspects may be something to consider as law enforcement begins to identify them,” Rasmussen said in an email.

She noted that some may try to evade identification and criminal charges, and said she is deeply concerned for the households and communities they might expose.

“I think really rigorous contact tracing of people who are not identified as being present on Capitol grounds will not be possible,” she said.

If you decided to read the names of every American who is known to have died of covid-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, at a rate of one per second starting at 5 p.m. Tuesday, you would not finish until a bit after 10 a.m. Saturday. Except, of course, that’s only including the deaths known as of writing; by then, we can expect 8,000 more deaths, pushing the recitation past noon.

Preliminary federal figures indicate that more than 3.2 million Americans will die over the course of 2020, the highest figure on record. It’s just a bit shy of 1 percent of the total population as of July 1, and about 1 in 10 of those deaths will be a result of covid-19.

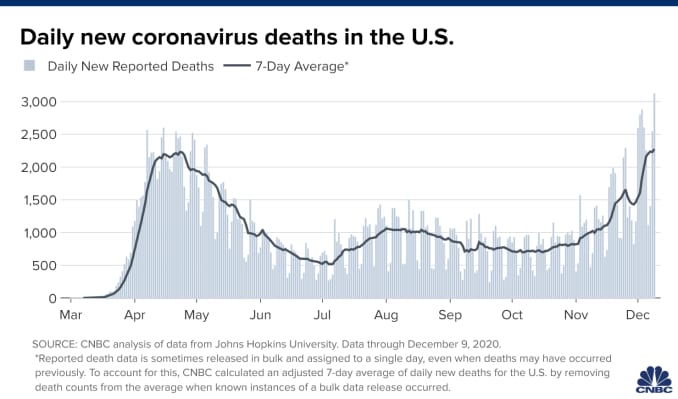

That’s the primary context in which any discussion about how the pandemic has affected the United States should occur. Secondarily, we should consider how the number of new coronavirus infections correlates to that figure. At the moment, nearly two people are dying of covid-19 each minute, a function of a massive surge in the number of new infections that began in mid-September.

The surge and the deaths are inextricable. For months, the number of new deaths on any given day has been about 1.8 percent of new cases several weeks prior. Allowing the virus to spread wildly means allowing more Americans to die.

In an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal, one of the architects of the decision to let the virus spread, former White House adviser Scott Atlas, blames the scale of the pandemic on the media. It’s the “politicization” of the virus, he argues, that has led to the dire outcomes we see, and that’s largely due to “media distortion.”

It’s hard to overstate both how dishonest Atlas’s argument is and how ironic it is that he should point the blame elsewhere. He makes false assertions about where states have been successful and suggests that mitigation efforts that weren’t 100 percent effective shouldn’t be used. He boasts that the effort to combat the spread of the virus was left to states — which is precisely the criticism aimed at President Trump’s administration. When Trump (and Atlas) undercut efforts to slow the spread of the virus, Trump supporters — including state leaders — picked up on that approach, contributing to the current spread.

Trump and Atlas shared the view that allowing the virus to spread was beneficial, as doing so increased population immunity. That another result would be surging deaths was met with a shrug or silence.

At the end of March, Trump offered one of his only forceful endorsements of slowing the spread of the virus. Having been presented with research indicating that as many as 2.2 million Americans would die of the virus if no effort was taken to limit its spread, he endorsed stay-at-home measures aimed at preventing new infections. His team suggested that implementing such mitigation efforts would keep the death toll under 240,000, with the added benefit of preventing hospitals from being overwhelmed.

This was one of Atlas’s arguments, too: Let the virus spread but backstop hospitals to prevent them from being flooded. The government accomplished the first goal, at least.

So we’ve raced past the 240,000-death mark, passing 300,000 deaths this month.

It’s important to remember, too, how often Trump himself promised this wasn’t going to be the country’s future. As the virus was spreading without detection — in part thanks to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s failure to develop a working test — Trump repeatedly downplayed how bad things would get. There were thousands of deaths around the world, he noted in early March, but less than a dozen in the United States. He compared the coronavirus to the seasonal flu and to the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, an event that had the politically useful characteristic of having occurred while Trump’s eventual opponent in the presidential election was vice president.

Over and over, Trump predicted a high-water mark for coronavirus deaths. Over and over, the country surged past his predictions. As the election approached, he began simply comparing the death toll to that 2.2-million-death figure he’d first introduced in March.

The United States will not reach 2.2 million coronavirus deaths over the course of the pandemic. We probably won’t reach 500,000, assuming that the national vaccination effort — the far-safer way to spread immunity — progresses without significant problems.

Right now, though, thousands of people are dying every day and tens of thousands more are on an inevitable path to the same result. More robust efforts to prevent new infections could have reduced these numbers, as robust efforts did elsewhere (contrary to Atlas’s theories). A consistent, forceful message from a president whose base is devoutly supportive of him would unquestionably have reshaped the virus’s spread. Had Trump embraced the expertise of government virologists, instead of a radiologist he saw on Fox News, it would have perhaps pushed the curve depicting the number of deaths each day back down instead of driving it higher.

This was the deadliest year in American history. Perhaps it would inevitably have been, given the size of the population (particularly the elderly population) and the emergence of covid-19. But it unquestionably didn’t have to be as deadly as it was.

A Florida taxi driver and his wife had seen enough conspiracy theories online to believe the virus was overblown, maybe even a hoax. So no masks for them. Then they got sick. She died. A college lecturer had trouble refilling her lupus drug after the president promoted it as a treatment for the new disease. A hospital nurse broke down when an ICU patient insisted his illness was nothing worse than the flu, oblivious to the silence in beds next door.

Lies infected America in 2020. The very worst were not just damaging, but deadly.

President Donald J. Trump fueled confusion and conspiracies from the earliest days of the coronavirus pandemic. He embraced theories that COVID-19 accounted for only a small fraction of the thousands upon thousands of deaths. He undermined public health guidance for wearing masks and cast Dr. Anthony Fauci as an unreliable flip-flopper.

But the infodemic was not the work of a single person.

Anonymous bad actors offered up junk science. Online skeptics made bogus accusations that hospitals padded their coronavirus case numbers to generate bonus payments. Influential TV and radio opinion hosts told millions of viewers that social distancing was a joke and that states had all of the personal protective equipment they needed (when they didn’t).

It was a symphony of counter narrative, and Trump was the conductor, if not the composer. The message: The threat to your health was overhyped to hurt the political fortunes of the president.

Every year, PolitiFact editors review the year’s most inaccurate statements to elevate one as the Lie of the Year. The “award” goes to a statement, or a collection of claims, that prove to be of substantive consequence in undermining reality.

It has become harder and harder to choose when cynical pundits and politicians don’t pay much of a price for saying things that aren’t true. For the past month, unproven claims of massive election fraud have tested democratic institutions and certainly qualify as historic and dangerously bald-faced. Fortunately, the constitutional foundations that undergird American democracy are holding.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus has killed more than 300,000 in the United States, a crisis exacerbated by the reckless spread of falsehoods.

PolitiFact’s 2020 Lie of the Year: claims that deny, downplay or disinform about COVID-19.

‘I always wanted to play it down’

On Feb. 7, Trump leveled with book author Bob Woodward about the dangers of the new virus that was spreading across the world, originating in central China. He told the legendary reporter that the virus was airborne, tricky and “more deadly than even your strenuous flus.”

Trump told the public something else. On Feb. 26, the president appeared with his coronavirus task force in the crowded White House briefing room. A reporter asked if he was telling healthy Americans not to change their behavior.

“Wash your hands, stay clean. You don’t have to necessarily grab every handrail unless you have to,” he said, the room chuckling. “I mean, view this the same as the flu.”

Three weeks later, March 19, he acknowledged to Woodward: “To be honest with you, I wanted to always play it down. I still like playing it down. Because I don’t want to create a panic.”

His acolytes in politics and the media were on the same page. Rush Limbaugh told his audience of about 15 million on Feb. 24 that coronavirus was being weaponized against Trump when it was just “the common cold, folks.” That’s wrong — even in the early weeks, it was clear the virus had a higher fatality rate than the common cold, with worse potential side effects, too.

As the virus was spreading, so was the message to downplay it.

“There are lots of sources of misinformation, and there are lots of elected officials besides Trump that have not taken the virus seriously or promoted misinformation,” said Brendan Nyhan, a government professor at Dartmouth College. “It’s not solely a Trump story — and it’s important to not take everyone else’s role out of the narrative.”

Hijacking the numbers

In August, there was a growing movement on Twitter to question the disproportionately high U.S. COVID-19 death toll.

The skeptics cited Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data to claim that only 6% of COVID-19 deaths could actually be attributed to the virus. On Aug. 24, BlazeTV host Steve Deace amplified it on Facebook.

“Here’s the percentage of people who died OF or FROM Covid with no underlying comorbidity,” he said to his 120,000 followers. “According to CDC, that is just 6% of the deaths WITH Covid so far.”

That misrepresented the reality of coronavirus deaths. The CDC had always said people with underlying health problems — comorbidities — were most vulnerable if they caught COVID-19. The report was noting that 6% died even without being at obvious risk.

But for those skeptical of COVID-19, the narrative confirmed their beliefs. Facebook users copied and pasted language from influencers like Amiri King, who had 2.2 million Facebook followers before he was banned. The Gateway Pundit called it a “SHOCK REPORT.”

“I saw a statistic come out the other day, talking about only 6% of the people actually died from COVID, which is very interesting — that they died from other reasons,” Trump told Fox News host Laura Ingraham on Sept. 1.

Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, addressed the claim on “Good Morning America” the same day.

“The point that the CDC was trying to make was that a certain percentage of them had nothing else but just COVID,” he said. “That does not mean that someone who has hypertension or diabetes who dies of COVID didn’t die of COVID-19 — they did.”

Trump retweeted the message from an account that sported the slogans and symbols of QAnon, a conspiracy movement that claims Democrats and Hollywood elites are members of an underground pedophilia ring.

False information moved between social media, Trump and TV, creating its own feedback loop.

“It’s an echo effect of sorts, where Donald Trump is certainly looking for information that resonates with his audiences and that supports his political objectives. And his audiences are looking to be amplified, so they’re incentivized to get him their information,” said Kate Starbird, an associate professor and misinformation expert at the University of Washington.Weakening the armor: misleading on masks

At the start of the pandemic, the CDC told healthy people not to wear masks, saying they were needed for health care providers on the frontlines. But on April 3 the agency changed its guidelines, saying every American should wear non-medical cloth masks in public.

Trump announced the CDC’s guidance, then gutted it.

“So it’s voluntary. You don’t have to do it. They suggested for a period of time, but this is voluntary,” Trump said at a press briefing. “I don’t think I’m going to be doing it.”

Rather than an advance in best practices on coronavirus prevention, face masks turned into a dividing line between Trump’s political calculations and his decision-making as president. Americans didn’t see Trump wearing a mask until a July visit to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

Meanwhile, disinformers flooded the internet with wild claims: Masks reduced oxygen. Masks trapped fungus. Masks trapped coronavirus. Masks just didn’t work.

In September, the CDC reported a correlation between people who went to bars and restaurants, where masks can’t consistently be worn, and positive COVID-19 test results. Bloggers and skeptical news outlets countered with a misleading report about masks.

On Oct. 13, the story landed on Fox News’ flagship show, “Tucker Carlson Tonight.” During the show, Carlson claimed “almost everyone — 85% — who got the coronavirus in July was wearing a mask.”

“So clearly (wearing a mask) doesn’t work the way they tell us it works,” Carlson said.

That’s wrong, and it misrepresented a small sample of people who tested positive. Public health officials and infectious disease experts have been consistent since April in saying that face masks are among the best ways to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

But two days later, Trump repeated the 85% stat during a rally and at a town hall with NBC’s Savannah Guthrie.

“I tell people, wear masks,” he said at the town hall. “But just the other day, they came out with a statement that 85% of the people that wear masks catch it.”

The assault on hospitals

On March 24, registered nurse Melissa Steiner worked her first shift in the new COVID-19 ICU of her southeast Michigan hospital. After her 13-hour day caring for two critically ill patients on ventilators, she posted a tearful video.

“Honestly, guys, it felt like I was working in a war zone,” Steiner said. “(I was) completely isolated from my team members, limited resources, limited supplies, limited responses from physicians because they’re just as overwhelmed.”

“I’m already breaking, so for f—’s sake, people, please take this seriously. This is so bad.”

Steiner’s post was one of many emotional pleas offered by overwhelmed hospital workers last spring urging people to take the threat seriously. The denialists mounted a counter offensive.

On March 28, Todd Starnes, a conservative radio host and commentator, tweeted a video from outside Brooklyn Hospital Center. There were few people or cars in sight.

“This is the ‘war zone’ outside the hospital in my Brooklyn neighborhood,” Starnes said sarcastically. The video racked up more than 1.5 million views.

Starnes’ video was one of the first examples of #FilmYourHospital, a conspiratorial social media trend that pushed back on the idea that hospitals had been strained by a rapid influx of coronavirus patients.

Several internet personalities asked people to go out and shoot their own videos. The result: a series of user-generated clips taken outside hospitals, where the response to the pandemic was not easily seen. Over the course of a week, #FilmYourHospital videos were uploaded to YouTube and posted tens of thousands of times on Twitter and Facebook.

Nearly two weeks and more than 10,000 deaths later, Fox News featured a guest who opened a new misinformation assault on hospitals.

Dr. Scott Jensen, a Minnesota physician and Republican state senator, told Ingraham that, because hospitals were receiving more money for COVID-19 patients on Medicare — a result of a coronavirus stimulus bill — they were overcounting COVID-19 cases. He had no proof of fraud, but the cynical story took off.

Trump used the false report on the campaign trail to continue to minimize the death toll.

“Our doctors get more money if somebody dies from COVID,” Trump told supporters at a rally in Waterford, Mich., Oct. 30. “You know that, right? I mean, our doctors are very smart people. So what they do is they say, ‘I’m sorry, but, you know, everybody dies of COVID.’”

The real fake news: The Plandemic

The most viral disinformation of the pandemic was styled to look like it had the blessing of people Americans trust: scientists and doctors.

In a 26-minute video called “Plandemic: The Hidden Agenda Behind COVID-19,” a former scientist at the National Cancer Institute claimed that the virus was manipulated in a lab, hydroxychloroquine is effective against coronaviruses, and face masks make people sick.

Judy Mikovits’ conspiracies received more than 8 million views in May thanks in part to the online outrage machine — anti-vaccine activists, anti-lockdown groups and QAnon supporters — that push disinformation into the mainstream. The video was circulated in a coordinated effort to promote Mikovits’ book release.

A couple of months later, a similar effort propelled another video of fact-averse doctors to millions of people in only a few hours.

On July 27, Breitbart published a clip of a press conference hosted by a group called America’s Frontline Doctors in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. Looking authoritative in white lab coats, these doctors discouraged mask wearing and falsely said there was already a cure in hydroxychloroquine, a drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

Trump, who had been talking up the drug since March and claimed to be taking it himself as a preventive measure in May, retweeted clips of the event before Twitter removed them as misinformation about COVID-19. He defended the “very respected doctors” in a July 28 press conference.

When Olga Lucia Torres, a lecturer at Columbia University, heard Trump touting the drug in March, she knew it didn’t bode well for her own prescription. Sure enough, the misinformation led to a run on hydroxychloroquine, creating a shortage for Americans like her who needed the drug for chronic conditions.

A lupus patient, she went to her local pharmacy to request a 90-day supply of the medication. But she was told they were only granting partial refills. It took her three weeks to get her medication through the mail.

“What about all the people who were silenced and just lost access to their staple medication because people ran to their doctors and begged to take it?” Torres said.No sickbed conversion

On Sept. 26, Trump hosted a Rose Garden ceremony to announce his nominee to replace the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the U.S. Supreme Court. More than 150 people attended the event introducing Amy Coney Barrett. Few wore masks, and the chairs weren’t spaced out.

In the weeks after, more than two dozen people close to Trump and the White House became infected with COVID-19. Early Oct. 2, Trump announced his positive test.

Those hoping the experience and Trump’s successful treatment at Walter Reed might inform his view of the coronavirus were disappointed.

Trump snapped back into minimizing the threat during his first moments back at the White House. He yanked off his mask and recorded a video.

“Don’t let it dominate you. Don’t be afraid of it,” he said, describing experimental and out-of-reach therapies he received. “You’re going to beat it.”

In Trump’s telling, his hospitalization was not the product of poor judgment about large gatherings like the Rose Garden event, but the consequence of leading with bravery. Plus, now, he claimed, he was immune from the virus.

On the morning after he returned from Walter Reed, Trump tweeted a seasonal flu death count of 100,000 lives and added that COVID-19 was “far less lethal” for most populations. More false claims at odds with data — the U.S. average for flu deaths over the past decade is 36,000, and experts said COVID-19 is more deadly for each age group over 30.

When Trump left the hospital, the U.S. death toll from COVID-19 was more than 200,000. Today it is more than 300,000. Meanwhile, this month the president has gone ahead with a series of indoor holiday parties.

The vaccine war

The vaccine disinformation campaign started in the spring but is still underway.

In April, blogs and social media users falsely claimed Democrats and powerful figures like Bill Gates wanted to use microchips to track which Americans had been vaccinated for the coronavirus. Now, false claims are taking aim at vaccines developed by Pfizer and BioNTech and other companies.

As is often the case with disinformation, the strategy is to deliver it with a charade of certainty.

“People are anxious and scared right now,” said Dr. Seema Yasmin, director of research and education programs at the Stanford Health Communication Initiative. “They’re looking for a whole picture.”

Most polls have shown far from universal acceptance of vaccines, with only 50% to 70% of respondents willing to take the vaccine. Black and Hispanic Americans are even less likely to take it so far.

Meanwhile, the future course of the coronavirus in the U.S. depends on whether Americans take public health guidance to heart. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation projected that, without mask mandates or a rapid vaccine rollout, the death toll could rise to more than 500,000 by April 2021.

“How can we come to terms with all that when people are living in separate informational realities?” Starbird said.

https://theintercept.com/2020/12/01/covid-health-officials-death-threats/

As people across the country refuse mask mandates, public health officials are fighting an uphill battle with little government support.

DR. MEGAN SRINIVAS was attending a virtual American Medical Association discussion around the “Mask Up” initiative one evening in July when she began to receive frantic messages from her parents begging her to confirm to them that she was all right.

“Somebody obtained my father’s unlisted cell phone number and spoofed him, making it look like it was a phone call coming from my phone,” she told Des Moines’s Business Record for a November profile. “Essentially they insinuated that they had harmed me and were on the way to their house to harm them.”

This malicious hoax, made possible by doxxing Srinivas’s private information, was only the most severe instance of abuse and harassment she had endured since she became a more visible proponent of mask-wearing and other mitigation measures at the beginning of Covid-19 pandemic. A Harvard-educated infectious disease physician and public health researcher on the faculty of the University of North Carolina, Srinivas currently lives and works in Fort Dodge, her hometown of 24,000 situated in the agricultural heart of northwest Iowa.

Srinivas is not just a national delegate for the AMA, but a prominent face of Covid-19 spread prevention locally, appearing on panels and local news segments. Fort Dodge itself is situated deep within Iowa’s 4th Congressional District, a staunchly conservative area that simply replaced white supremacist Rep. Steve King with a more palatable Republican.Join Our NewsletterOriginal reporting. Fearless journalism. Delivered to you.I’m in

Basic health measures promoted by Srinivas in Iowa since the beginning of the pandemic have been politicized along the same fault lines as they have across the rest of the country. Some remain in the middle ground, indifferent to health guidelines out deep attachment to “normal” pre-pandemic life. Others have either embraced spread-prevention strategies like mask-wearing or refused to acknowledge the existence of the virus at all. In a red state like Iowa, an eager audience for President Donald Trump’s misinformation about the dangers of the coronavirus has made the latter far more common, which has made Srinivas’s job more difficult and more dangerous.

“It was startling at first, the volume at which [these threats were] happening,” Srinivas told The Intercept. “I know people get very heated about politics and the issues that people advocate for in general, but especially on something like this where it’s merely trying to provide a public service, a way people can protect themselves and their loved ones and community based on medical objective facts. That’s surprising that this is the reaction people have.”

“I have trolls like other people, I’ve been doxxed, I’ve gotten death threats,” she said. “When you say anything people don’t want to hear, there will be trolls and there will be people who will try to argue against you. The death threats were something I wish I could say were new, but when I’ve done things like this in the past, I’ve had people say not-so-nice things in the past when I’ve had advocacy issues.”An untenable pressure has been placed on public health workers thrust in a politicized health crisis — and that pressure only appears to be worsening.

At the same time, as an Iowa native, Srinivas has been able to gain some trust through tapping into local networks like Facebook. Though she has encountered a great deal of anger, she’s also seen success in the form of a son who’s managed to convince his diabetic father, a priest, to hold off on reopening his church thanks to her advice, and through someone who’s been allowed to work from home based on recommendations Srinivas made on a panel.

“At this point, almost everyone knows at least one person that’s been infected. Unfortunately, it leads to a higher proportion of the population who knows someone who’s not just been infected, but who’s had serious ramification driven by the disease,” Srinivas said. “So it’s come to the point where, as people are experiencing the impact of the disease closer to home, they’re starting to understand the true impact and starting to be willing to listen to recommendations.”

Without cooperation and support at the state level, however, what Srinivas can accomplish on her own is limited. Even as the number of Covid-19 cases grew and put an increasing strain on Iowa’s hospitals over the past few months, it took until after the November election for Iowa’s Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds to tighten Iowa’s mask guidance. And board members in Webster County, where Srinivas lives, only admitted in November that she had been right to advocate for a mask mandate all along. Though Trump lost the election nationally, he won Iowa by a considerable margin, which Reynolds has claimed as a vindication of her “open for business” attitude and has continued downplaying the pandemic’s severity.

“The issue with her messaging is it creates a leader in the state that should be trusted who’s giving out misinformation,” Srinivas said. “Naturally, people who don’t necessarily realize that this is misinformation because it’s not their area of expertise want to follow what their leader is saying. That’s a huge issue under the entire public health world right now, where we have a governor that is spreading falsehood like this.”

The embattled situation in which Srinivas has found herself is the new normal for public health officials attempting to stem the tide of a deadly viral outbreak, particularly in the middle of country where the pandemic winter is already deepening. Advocating for simple, potentially lifesaving measures has become a politically significant act, working to inform the public means navigating conflicting regulatory bodies, and doing your job means making yourself publicly vulnerable to an endless stream of vitriol and even death threats. The result across the board is that an untenable pressure has been placed on public health workers thrust in a politicized health crisis — and that pressure only appears to be worsening.

DESPITE THE FACT that Wisconsin’s stay-at-home order was nullified by the state’s Supreme Court in May, the Dane County Health Department has used its ability to exercise local control in an attempt to install mitigation measures that go beyond those statewide. By issuing a mask mandate ahead of a statewide rule and advocating for education and compliance efforts, the department currently considers itself in a good place regarding health guideline compliance.

These actions have drawn a lot of ire from those unhappy with the regulations, however. According to a communications representative for the department, anti-maskers have held a protest on a health officer’s front lawn, a staff member was “verbally assaulted” in a gas station parking lot (an incident that prompted the department to advise its employees to only wear official clothing to testing sites), and employees performing compliance checks on businesses have been told to never perform these checks alone after “instances of business owners get a little too close for comfort.” They’ve also received a number of emails accusing health workers of being “Nazis,” “liars,” “political pawns,” and purely “evil.”

In Kansas’s Sedgwick County, Wichita — the largest city in the state — has been considering new lockdown measures after a November surge in coronavirus cases has threatened to overwhelm its hospitals. Though Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly attempted to instate a mask mandate in July, 90 of the state’s 105 counties rejected it, including Sedgwick, though the health board issued its own directive and Wichita had installed its own at the city level.

Now, with cases surging again, just as Srinivas saw the number of believers rising as more got sick, counties in Kansas that previously resisted mask mandates are changing their tune after Kelly announced a new mandate. But Sedgwick County health officials see an intractable line in the sand when it comes to who’s on board with mitigation measures and are focused more on what those who are already on board need to be told.

“It seems like a lot of the naysayers are naysayers and the supporters are supporters,” Adrienne Byrne, director of Sedgwick County Health Department, said. “There’s some people that are just kind of whatever about it. We just remind people to wear masks, it does make a difference. As we’ve gone on, studies have shown that it works.”

“I think it’s important to acknowledge to people that it is tiring, to acknowledge and validate their experience that people want to be over this stuff, but it’s important to reinforce that we are in a marathon,” she said. “In the beginning, we all wanted to hear that we would reach a magical date and we would be done with this stuff.”

Sedgwick has managed the streams of angry messages but has seen her colleagues in rural counties endure far worse, including death threats. She knows of one public health worker in Kansas who quit after being threatened, and others who have cited the strain of the politicized pandemic as their reason for leaving the public health profession.

“We’re certainly losing some health officials, there’s no question about that,” said Georges Benjamin, president of the American Public Health Association. “In the long arc of history, public health officials are pretty resilient. And while it absolutely will dissuade people from entering the field, we all need to do a better job of equipping them for these issues in the future.”

Benjamin would like to see institutional and public support for public health workers resemble that given to police or firefighters, government professionals who are well-funded, believed to be essential to the functioning of society, and wielding a certain level of authority.

“For elected officials who are charged with protecting the officials and their public officials, our message to officials then is that they should protect their employees,” Benjamin said.

IN RURAL NEBRASKA, the situation has presented even more complex challenges to public health workers. Outside of Omaha, the rural expanse is ruled by a deeply entrenched conservatism and, like Iowa’s governor Reynolds, Nebraska’s Republican Gov. Pete Ricketts has resisted a mask mandate. The Two Rivers Public Health Department, which oversees a wide swath of central Nebraska and its biggest population center, Kearney (population 33,000), is a popular pit stop along the Interstate 80 travel corridor and home to a University of Nebraska outpost.

Prior to the pandemic, Nebraska’s decentralized public health system had seen significant atrophy, according to Two Rivers Health Director Jeremy Eschliman, and was wholly unprepared for this level of public health event. There were few epidemiologists to be found outside of Omaha, though the department was able to hire one earlier this year. It also became clear early on that, despite the department’s traditionally strong ties with local media, messaging around the pandemic would be an uphill battle to get people to adapt new habits, especially when the president was telling them otherwise.

“There was one clear instance I remember when I caught a bit of heckling when I said, ‘Hey, this is serious. We’re going to see significant death is what the models show at this point in time,’” Eschliman said. “[The station said], ‘Are you serious? That seems way out in left field’ or something to that effect. That station had a very conservative following and that was the information they received.”

Eschliman has taken a realistic stance to promoting mask-wearing, thinking of it as akin to smoking. (“You could walk up to 10 people and try to tell them to quit smoking and you’re not going to get all 10 to quit,” he said. “Fun fact: You’re not going to get more than maybe one to even quit for a small period of time.”) Over the summer, he traveled just over Nebraska’s southern border into Colorado, where he was struck by the night-and-day difference between his neighbor state’s adoption of mask-wearing and Nebraskan indifference to it, each following the directives of their state leaders.“It’s become very difficult to do the right thing when you don’t have the political support to do so.”

Home rule is the law of the land in Nebraska, and there’s been strong rural opposition to mask mandates, despite more liberal population centers like Lincoln and Omaha installing their own. It’s taken Kearney until November 30 to finally install its own after outbreaks at the college and in nursing homes. Public health care workers have also been left on their own to make controversial decisions that have caused political friction. In May, the local health board voted not to share public health information with cities and first responders due to what they decided were issues of information confidentiality.

“Mayors, county board members, and police chiefs ran a sort of a smear campaign against me and the organization,” Eschliman said. “So when we talk about resiliency, that’s what we’re dealing with. It’s become very difficult to do the right thing when you don’t have the political support to do so.”

Even having a Democratic governor doesn’t necessarily ensure that support. In Hill County, a sparsely populated region of Montana’s “Hi-Line” country along the Canadian border, Sanitarian Clay Vincent supports Gov. Steve Bullock’s mask mandate, but doesn’t understand why it exists if it’s not enforceable. The way he sees it, if laws are made, they should create consequences for those who refuse to follow them.

But Vincent and the Hill County Health Board also saw what happened elsewhere in the state, in Flathead County, where lawsuits were brought against five businesses who refused to follow Bullock’s mask mandate. After a judge threw the lawsuit out, those businesses launched a countersuit against the state, alleging damages. In order to bring businesses in Hill County into compliance with the mask mandate, the health board is considering slapping them with signs identifying them as health risks or, barring that, simply asking them to explain their refusal to comply.

“These are community members. Everybody knows everybody and [the board isn’t] trying to make more of a division between those who are and those who are not, but I come back to the fact that public laws are put there for the main reason to protect the public from infectious diseases,” Vincent said. “You have to support the laws, or people sooner or later don’t give any credence to the public health in general.”

Regardless of whether they can push the Hill County businesses into compliance, the political winds are already changing in Montana. Republican Gov.-elect Greg Gianforte will take power in January and likely bring the party’s aversion to mask mandates with him. President-elect Joe Biden will take power at the same time, and even if he attempts to install a nationwide mask mandate, it will likely be difficult to enforce and may end up meaning little out in Montana. It will also likely exacerbate ongoing tensions in communities throughout the state. The building that houses Hill County Health Department in the town of Havre was already closed this summer out of fear that a local group opposed to the mask mandate and nurses doing contract tracing are routinely threatened in the course doing their jobs.

Regardless, Vincent is determined to encourage and enforce public health guidelines as much as it’s in his power to do so, no matter the backlash. He sees protecting the public as no different than preventing any other kind of disease. “I don’t care if it’s hepatitis or HIV or tuberculosis or any of these things,” he said. “You’re expected to deal with those and make sure it’s not affecting the public. Otherwise you have a disaster.”