“Follow the money,” was the advice of Deep Throat to the Watergate journalists. But now, new Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan says that’s not enough when analyzing monopolies in both healthcare and rest of the economy. Follow the algorithms and follow the power, too, not just the money.

We all know how monopolies harm consumers with higher prices. But monopolies and powerful corporations cause harm in other ways. Some examples:

- Facebook using algorithms that “wire” teenage girls to engage with it (and boost Facebook’s profits) but “probably” hurt their mental health

- Sackler family and Purdue Pharma “recklessly” inducing doctors to prescribe unnecessary opioids, often leading to abuse and diversion, prioritizing “money over the health… of patients”

- Media outlets on both the Right and the Left boosting ratings and ad revenue by stoking fear and outrage

- Joe Manchin (D-WV) scuttling carbon-mitigation legislation while profiting from coal interests

- Remington Arms baiting insecure men to buy guns as a badge of masculinity, with tragic results in the case of the Sandy Hook mass murder.

Not all of these examples are linked directly to potentially illegal anticompetitive activities. But all are linked to the exercise of insufficiently checked corporate power. Commissioner Khan has signaled that she will consider such harms when analyzing mergers and other potentially anticompetitive activities.

This expanded view of anticompetitive harm is a departure from Robert Bork’s more narrow approach to antitrust enforcement taken by the F.T.C. since publication of Bork’s 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox. Bork noted that in many cases, mergers resulted in economies of scale that lowered prices for consumers. By his standard, such mergers were permissible as benefiting the consumer.

But now Commissioner Khan – and others like-minded theorists called neo-Brandeisians – point to the other harmful effects beyond the seeming benefit of lower prices. For example, the flip-side of a monopoly’s position as seller is its monopsony as a purchaser of labor. If there is only one big potential employer, workers do not have a competitive labor market, depressing their bargaining power and wages. In the digital economy there is also potential jeopardy to data privacy and security, and coercion to use certain digital products. Think the teenage girls on Instagram.

Employees of a single powerful employer are also inhibited from rocking the boat with innovations, critiques, or whistleblowing. This enervates a truly competitive marketplace.

Commissioner Khan views the antitrust issue not as being one of bigness but rather of power, power that reduces true competition. Beyond merely looking at prices, she seeks to identify and quantify the other elements of power and competition.

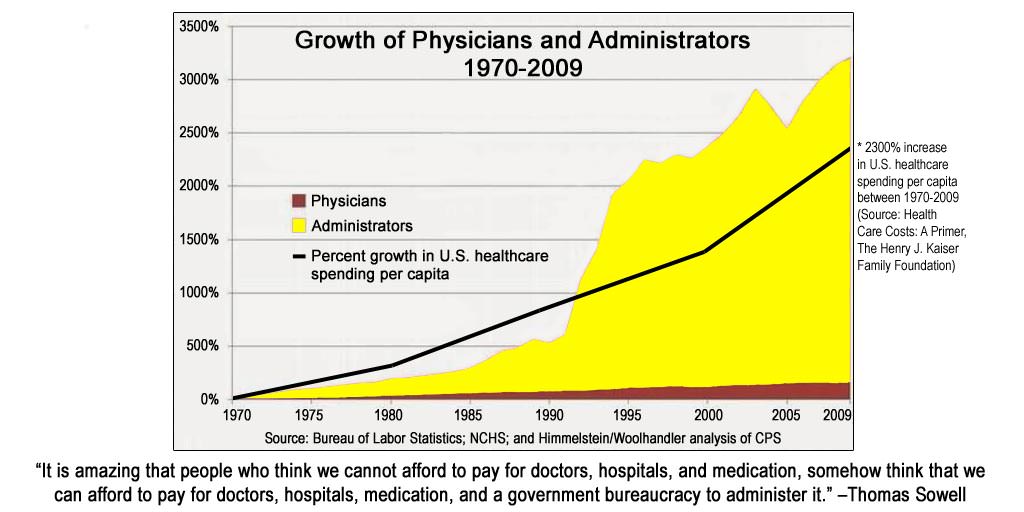

This blog has implicated healthcare monopolies as one direct cause of relentless increases in spending. It has also embraced the view of Steven Brill that “over the last five decades a new ‘best and brightest’ meritocracy rigged not only healthcare, but also the entire American financial, legal, and political system to build ‘moats’ of protection to perpetuate their wealth and power.”

Commissioner Khan is now highlighting a key mechanism – anticompetitive political and financial power — by which healthcare corporations rig healthcare and by which other corporations have blocked reform in pursuit of short-sighted profits. She summarizes the remedy:

If you allow unfettered monopoly power to concentrate, its power can rival that of the state., right? And historically, the antitrust laws have a rich tradition and rich history, and a key goal was to ensure that our commercial sphere was characterized by the same types of checks and balances and protections against concentration of economic power that we had set up in our political and governance sphere. And so the desire to kind of check those types of concentrations of power, I think, is deep in the American tradition.

This blog thinks she is on the right track. Because healthcare reform is in the public interest and must be pursued even in the face of powerful special interests.

Take Action

Now, take action.