Category Archives: Talent Management

Snapshot Analysis Shows ‘Unprecedented’ Decline in RN Workforce

The number of registered nurses plunged by 100,000 in 2021, representing the steepest drop in the RN workforce in 4 decades, according to a new analysis.

From 2019 to 2021, the total workforce size declined by 1.8%, including a 4% drop in the number of RNs under the age of 35, a 0.5% drop in the number of those ages 35 to 49, and a 1.0% drop in the number of those over 50, reported David Auerbach, PhD, of the Center for Interdisciplinary Health Workforce Studies at Montana State University College of Nursing, and colleagues in Health Affairs Forefront.

“The numbers really are unprecedented,” Auerbach told MedPage Today.

“But … given all that we’ve been hearing about burnout, retirement, job switching, and shifting,” and all of the ways the pandemic disrupted the labor market, including healthcare, “I am not super surprised either,” he added.

While Auerbach said he and his co-authors can’t definitively say what caused this shift, he does not think it’s merely a problem of “entry and education” — in other words, fewer people choosing nursing as a career.

There have been no “major changes” in the enrollment and graduation rates reported by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), and the number of RNs completing the National Council Licensure Examination actually increased in 2020 versus 2019, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, Auerbach said.

This suggests that the decline in younger RNs is more likely due to nurses “either pausing or leaving nursing. What we really don’t know is whether this is a temporary or more permanent phenomenon,” he added.

The overall decline was not spread evenly across sites, but instead was “entirely due” to a 3.9% reduction in hospital employment, offset by a 1.6% increase in nursing employment in other settings, the authors said.

For decades, the RN workforce grew steadily, from 1 million nurses in 1982 to 3.2 million in 2020. Though the profession saw a rocky period in the late 1990s, during which growth looked less certain, millennials reversed this temporary downward trend in the early 2000s, Auerbach and team explained.

In a prior Health Affairs analysis, Auerbach and colleagues found that the labor market for nurses had “plateaued” during the first 15 months of the pandemic.

Auerbach’s team had previously projected that the supply of nurses would grow 4.4% from 2019 to 2021.

The data may reflect a mix of RNs leaving “outright” and those shifting to non-hospital jobs. The authors were unable to follow the same people from pre-pandemic to now, Auerbach noted. “Based on taking a snapshot of the world in 2019 and then taking another snapshot of the world in 2021, we’re inferring from what we see what we think might have happened.”

Auerbach said that he and his colleagues are close to ruling out childcare problems as a core reason for younger nurses departing. “We didn’t see some huge reduction in nurses with kids at home,” he explained.

However, if that had been the case, then the decline might be seen as something temporary that could be “ironed out,” compared to more deeply rooted structural problems, like poor working conditions, he said.

Auerbach and colleagues stressed that more needs to be done to help early-career nurses who have endured a “trial by fire” during the pandemic, and that “more effective strategies” must be leveraged to reward nurses who have stayed on the front lines and to bring back those who have left.

On a hopeful note, Auerbach pointed to recent AACN data, which showed a “big jump” in the number of applications to nursing schools. Additionally, prior research found that “times of natural disaster or health crisis could increase interest in RN careers,” the authors noted.

“That doesn’t sound like people are just going to abandon nursing altogether,” Auerbach said.

Don’t pin your hopes on the “Great Regret”

Businesses who suffered from the Great Resignation, in which large numbers of workers voluntarily resigned during the pandemic looking for more fulfilling work or higher wages, are now hoping the “Great Regret” might bring workers back. According to recent surveys, over 70 percent of workers who switched employment during the pandemic found that their new jobs didn’t live up to their expectations, and nearly half wish they had their old job back.

After scores of nurses left hospital positions for travel roles, health system leaders are seeing some nurses return. One physician told us about a favorite nurse on his oncology unit who returned from over a year as a traveler, ready to settle down and be closer to family.

A chief nursing officer relayed that her system was seeing nurses who took agency positions to work toward personal financial goals, like earning a down payment for a house, wanting to come back now that they’ve reached it: “Travel roles are intense, and most nurses can’t do them forever”.

But other nursing leaders caution that they’re preparing for agency nurses to become a permanent fixture in the workforce: “More nurses will see travel as an option for different points in their career, when they have personal flexibility or need the extra money”.

The “Great Regret” might help some hospitals lessen their reliance on agency nursing in the short-term. But building a stable clinical workforce will require addressing underlying structural challenges, through changes in education, rethinking job roles and care models, and finding ways to build individualized job flexibility and customization.

Retail wages are rising. Can hospital pay keep up?

While healthcare workers battle burnout, hospitals have been ramping up wages and other benefits to recruit and retain workers. It has created a culture of competition among health systems as well as travel agencies that offer considerably higher pay.

But other healthcare organizations are not hospitals’ only competitors. Some hospitals, particularly those in rural areas, are struggling to match rising employee pay among nonindustry employers such as Target and Walmart.

“We monitor and we’ve been looking and we ask around in the community and we can ask who’s paying what,” Troy Bruntz, CEO of Community Hospital in McCook, Neb., told Becker’s. “So we know where Walmart is on different things, and we’re OK. But if Walmart tried to match what Target’s doing, that would not be good.”

At Target, the hourly starting wage now ranges from $15-$24. The organization is making a $300 million investment total to boost wages and benefits, including health plans. Starting pay is dependent on the job, the market and local wage data, according to NPR.

Walmart raised the hourly wages for 565,000 workers in 2021 by at least $1 an hour, The New York Times reported. The company’s average hourly wage is $16.40, with the lowest being $12 and the highest being $17.

Meanwhile, Costco raised its minimum wage to $17 an hour, according to NPR. The federal minimum wage is $7.25.

Estimated employment for healthcare practitioners and technical occupations is 8.8 million, according to the latest data released March 31 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. This includes nurse practitioners, physicians, registered nurses, physician assistants and respiratory therapists, among others.

In sales and related occupations, estimated employment is 13.3 million, according to the bureau. This includes retail salespersons, cashiers and first-line supervisors of retail salespersons, among others.

While retail companies up their wages, at least one hospital CEO is monitoring the issue.

Healthcare leaders weigh their options

Mr. Bruntz said rising wages among retailers is an issue his organization monitors. Although Target does not have a store in McCook, there is a Walmart, where pay is increasing.

“I was quoted a few months ago saying Walmart was approaching $15 an hour, and we can handle that,” Mr. Bruntz said. “But when it gets to $20 or $25, it’s going to be an issue.”

He also said he cannot solely increase the wages of the people making less than $15 or less than $25 because he has to be fair in terms of wages for different types of roles.

Specifically, he said he is concerned about what matching rising wages at retailers would mean for labor expenses, which make up about half of the hospital’s cost structure.

“I double that half, that’s 25 percent more expenses instantly,” Mr. Bruntz said. “And how is that going to ratchet to a bottom line anything less than a massive negative number? So it’s a huge problem.”

Clinical positions are not the only ones hospitals and health systems are struggling to fill; they are encountering similar difficulties with technicians and food service workers. Regarding these roles, competition from industries outside healthcare is particularly challenging.

This is an issue Patrice Weiss, MD, executive vice president and chief medical officer of Roanoke, Va.-based Carilion Clinic, addressed during a Becker’s panel discussion April 4. The organization saw workforce issues not just in its clinical staff, but among environmental services staff.

“When you look at what … even fast food restaurants were offering to pay per hour, well gosh, those hours are a whole lot better,” she said during the panel discussion. “There’s no exposure. You’re not walking into a building where there’s an infectious disease or patients with pandemics are being admitted.”

Amid workforce challenges, Community Hospital is elevating its recruitment and retention efforts.

Mr. Bruntz touted the hospital as a hard place to leave because of the culture while acknowledging the monetary efforts his organization is making to keep staff.

He said the hospital has a retention program where full-time employees get a bonus amount if they are at the employer on Dec. 31 and have been there at least since April 15. Part-time workers are also eligible for a bonus, though a lesser amount.

“It also encourages staff [who work on an as-needed basis] to go part-time or full-time, and [those who are] part-time to go full-time,” Mr. Bruntz said. “That’s another thing we’re doing is higher amounts for higher status to encourage that trend.”

Additionally, Community Hospital, which has 330 employees, offers a referral bonus to staff to encourage people they know to come work with them.

“We want staff to bring people they like. [We are] encouraging staff to be their own ambassadors for filling positions,” Mr. Bruntz said.

He said the hospital also will offer employees a sizable market wage adjustment not because of competition from Walmart but because of inflation.

Graham County Hospital in Hill City, Kan., is also affected by the tight labor market, although it has not experienced much competition with retail companies, CEO Melissa Atkins told Becker’s. However, the hospital is struggling with competition from other healthcare organizations, particularly when it comes to patient care departments and nursing. While many hospitals have struggled to retain employees from travel agencies, Graham County Hospital has mostly been able to avoid it.

“As the demand increases, so does the wage,” Ms. Atkins said. “In addition to other hospitals offering sign-on bonuses and increased wages, nurse agency companies are offering higher wages for traveling nurse aides and nurses. We are extremely fortunate in that we have not had to use agency nurses. Our current staff has stepped up and filled in the shortages [with additional incentive pay].”

To combat this trend, the hospital has increased hourly wages and shift differentials, as many healthcare organizations have done. It has also provided bonuses using COVID-19 relief funds.

Overall, Mr. Bruntz said he prefers “not to get into an arms race with wages” among nonindustry competitors.

“It’s not going to end well for anybody. We prefer not to use that,” he said. “At the same time, we’re trying to do as much as possible without being in a full arms race. But if Walmart started paying $25 for a door greeter and cashier, we would have to reassess.”

More than 4K Stanford nurses vote to strike in California

UPDATE: April 14, 2022: Nurses will begin striking April 25 if they are unable to reach a deal with the system by then, according to a Wednesday statement from the union. The two sides have met with a federal mediator three times, and the strike would be open-ended.

Dive Brief:

- Unionized nurses at Stanford hospitals in California voted in favor of authorizing a strike Thursday, meaning more than 4,500 nurses could walk off the job in a bid for better staffing, wages and mental health measures in new contracts.

- Some 93% of nurses represented by the Committee for Recognition of Nursing Achievement voted in favor of the work stoppage, though the union did not set a date, according to a union release. It must give the hospitals 10 days notice before going on strike.

- Nurses’ contracts expired March 31 and the union and hospital have engaged in more than 30 bargaining sessions over the past three months, including with a federal mediator, according to the union.

Dive Insight:

As the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened working conditions for nurses, some unions have made negotiating contracts a priority. Better staffing is key, along with higher wages and other benefits to help attract and retain employees amid ongoing shortages.

The California nurses’ demands in new contracts focus heavily on recruitment and retention of nursing staff “amid an industry-wide shortage and nurses being exhausted after working through the pandemic, many in short-staffed units,” the union said in the release.

They’re also asking for improved access to time off and more mental health support.

Nurses say their working conditions are becoming untenable and relying on travel staff and overtime shifts is not sustainable, according to the release.

The hospitals are taking precautionary steps to prepare for a potential strike and will resume negotiations with the union and a federal mediator Tuesday, according to a statement from Stanford.

But according to CRONA, nurses have filed significantly more assignment despite objections documents from 2020 to 2021 — forms that notify hospital supervisors of assignments nurses take despite personal objections around lacking resources, training or staff.

And a survey of CRONA nurses conducted in November 2021 founds that as many as 45% were considering quitting their jobs, according to the union.

That’s in line with other national surveys, including one from staffing firm Incredible Health released in March that found more than a third of nurses said they plan to leave their current jobs by the end of this year.

The CRONA nurses “readiness to strike demonstrates the urgency of the great professional and personal crisis they are facing and the solutions they are demanding from hospital executives,” the union said in the release.

No major strikes among healthcare workers have occurred so far this year, though several happened in 2021 and in 2020, the first year of the pandemic.

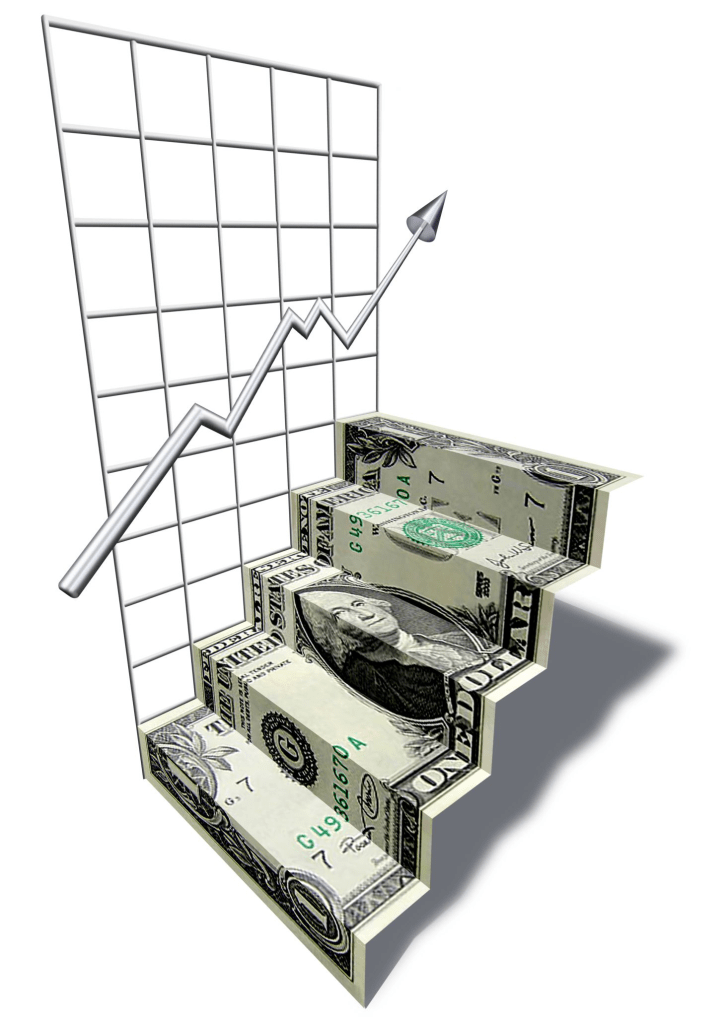

Rising turnover, agency costs compound hospital labor problems

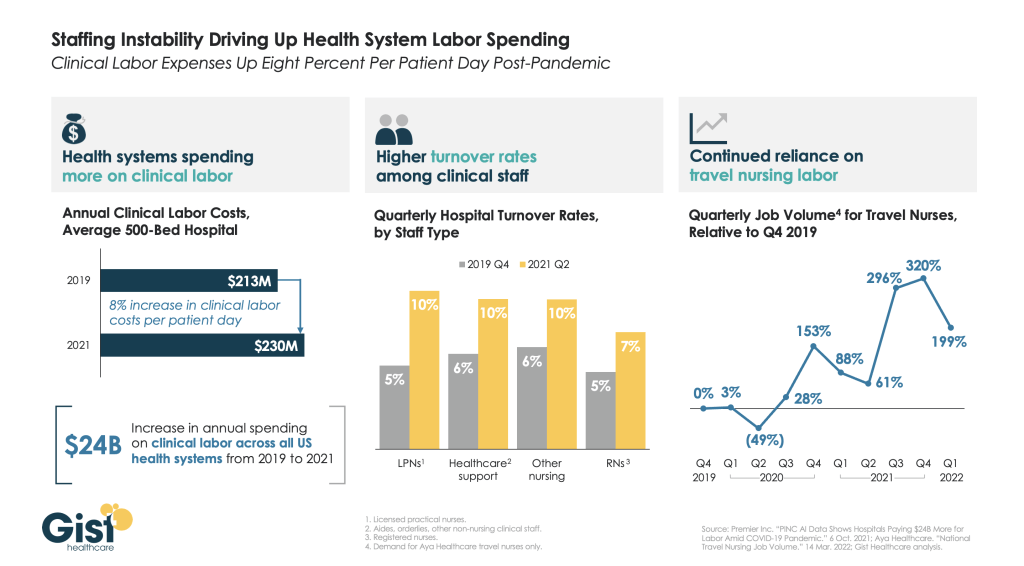

Even as COVID admissions continue to wane, hospitals report that workforce shortages persist. The impact on hospital finances is stark: as shown in the graphic above, there has been an eight percent increase in clinical labor costs per patient day since the start of the pandemic, amounting to an additional $17M annually for an average 500-bed hospital.

Two of the primary factors driving this increase—higher turnover among clinical staff and a continued reliance on travel nurses—are mutually reinforcing.

Quarterly turnover rates for some nursing positions doubled from Q4 2019 to Q2 2021, as hospitals turned to expensive agency labor to fill resulting vacancies. Spiking demand for travel nurses, still running nearly three times higher than the pre-pandemic baseline, fueled more turnover, as more nurses left for these lucrative roles.

It’s unclear how long increased labor costs will persist.

Some HR tactics, like signing and retention bonuses, are one-time expenditures. But total hospital employment is still down two percent from pre-pandemic levels, pointing to a diminished healthcare labor supply.

Permanent wage increases may end up being unavoidable, especially for lower-wage jobs, where a new compensation baseline for talent is being set by the market, both inside and outside the healthcare industry.

Cartoon – Opening in Accounting

Viewpoint: It’s the Great Aspiration, not Resignation

Those who left their jobs during the Great Resignation did so out of more than just frustration, but instead used it as an opportunity to follow their dreams and aspirations, writes Whitney Johnson, CEO of Disruption Advisors, a talent development company, in the Harvard Business Review April 6.

The pandemic forced many people to reevaluate many facets of their lives, from where to live to how to spend more time with family. Ms. Johnson argues that workers’ thoughts on changing the way they work is a good thing, giving workers agency to discover new aspirations and proactively seek them.

“The Great Resignation appellation is, I believe, mistaken. Most workers are not simply quitting. They are following a dream refined in pandemic adversity. They are aspiring to grow in the ways most important to them,” she writes.

Even for those who have been forced out of the workforce, like working mothers and caregivers, Ms. Johnson argues that it will lead to a boom of innovative new businesses, created by those resourceful workers who find another way to work outside the realms of traditional industry.

She also states that this “great aspiration” is beneficial for employers too, who can make the most of a fresh pool of talent, full of newly motivated employees who are dedicated and searching for meaning.

Cartoon – You’re not happy with your job

Hospital CEOs are joining the Great Resignation

The number of departing hospital CEOs is on the rise as C-level executives are grappling with challenges tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Twelve hospital CEOs exited their roles in January, double the number who stepped down from their positions in the same month a year earlier, according to a report from Challenger, Gray & Christmas, an executive outplacement and coaching firm.

While some hospital and health system CEOs are retiring, others are stepping down from their posts into C-level roles at other organizations. At least eight hospital and health system CEOs have stepped down from their positions since mid-February.

The increase in CEO departures isn’t unique to healthcare. More than 100 CEOs of U.S.-based companies left their posts in January, up from 89 in the same month a year earlier, according to the Challenger, Gray & Christmas report.

The uptick in executive exits shouldn’t be surprising given the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, experts told NBC News. CEOs and other executives aren’t immune to the pressures that are prompting people to leave their jobs.

“It’s many factors — the burnout, the pandemic, the school closures, the need to take stock of life,” Julia Pollack, chief economist at ZipRecruiter, told NBC News in January. “It’s a whole wide range of shocks.”