Cartoon – Modern Communication Management

Nurse staffing ratios are one of the most hotly debated issues within the nursing profession. Those in favor say the limits improve patient safety and care. Those against them say ratios don’t account for patient acuity and would create a financial burden on hospitals and healthcare systems.

Now the public gets to weigh in on the issue. On Nov. 6, Massachusetts voters will face ballot Question 1, which would implement nurse to patient ratios in hospitals and other healthcare settings. The ratios vary according to the type of unit and level of care provided.

The Massachusetts Nurses Association supports the law, while hospitals, health systems and some other nursing professional organizations oppose it.

Both sides have pumped millions of dollars into the debate.

Voters seem to be split on the issue as well.

According to an October 25 to 28 WBUR poll, 58% of voters say they are against Question 1. This is a change from September when respondents to a previous WBUR poll were more evenly split with 44% in favor, 44% against, and 12% undecided.

Massachusetts is not completely unfamiliar with nurse-patient staffing ratios. In 2014, Massachusetts passed a law requiring 1-to-1 or 2-to-1 patient-to-nurse staffing ratios in intensive care units, as guided by a tool that accounts for patient acuity and anticipated care intensity.

However, an analysis by physician-researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center found those regulations were not associated with improvements in patient outcomes.

Should the law pass, Massachusetts will join California as the only other state to require this level of mandatory ratios. In California, the law supporting ratios was passed in 1999 and was then rolled out in a staggered fashion until it was in full-effect in 2004.

Will mandatory ratios become a reality for those in the Baystate? That will be known, most-likely, in just a few short days.

Betsy Foster and Doug Dillon are devotees of Josh Harder. The Democratic upstart is attempting to topple Republican incumbent Jeff Denham in this conflicted, semi-rural district that is home to conservative agricultural interests, a growing Latino population and liberal San Francisco Bay Area refugees.

To Foster’s and Dillon’s delight, Harder supports a “Medicare-for-all” health care system that would cover all Americans.

Foster, a 54-year-old campaign volunteer from Berkeley, believes Medicare-for-all is similar to what’s offered in Canada, where the government provides health insurance to everybody.

Dillon, a 57-year-old almond farmer from Modesto, says Foster’s description sounds like a single-payer system.

“It all means many different things to many different people,” Foster said from behind a volunteer table inside the warehouse Harder uses as his campaign headquarters. “It’s all so complicated.”

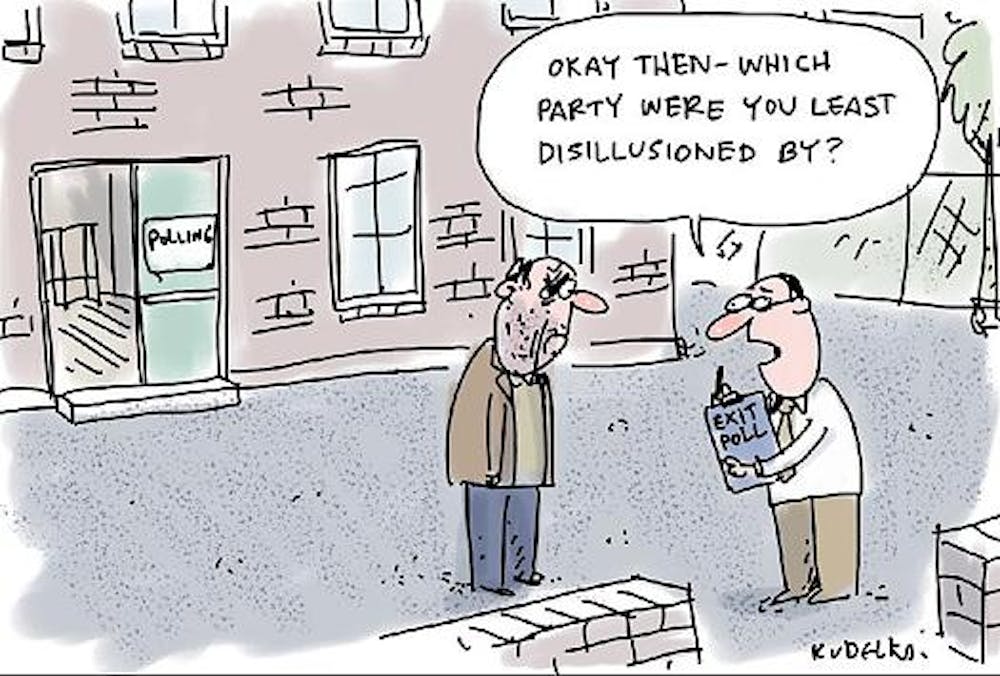

Across the country, catchphrases such as “Medicare-for-all,” “single-payer,” “public option” and “universal health care” are sweeping state and federal political races as Democrats tap into voter anger about GOP efforts to kill the Affordable Care Act and erode protections for people with preexisting conditions.

Republicans, including President Donald Trump, describe such proposals as “socialist” schemes that will cost taxpayers too much. They say their party is committed to providing affordable and accessible health insurance, which includes coverage for preexisting conditions, but with less government involvement.

Voters have become casualties as candidates toss around these catchphrases — sometimes vaguely and inaccurately. The sound bites often come across as “quick answers without a lot of detail,” said Gerard Anderson, a professor of public health at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School Public Health.

“It’s quite understandable people don’t understand the terms,” Anderson added.

For example, U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) advocates a single-payer national health care program that he calls Medicare-for-all, an idea that caught fire during his 2016 presidential bid.

But Sanders’ labels are misleading, health experts agree, because Medicare isn’t actually a single-payer system. Medicare allows private insurance companies to manage care in the program, which means the government is not the only payer of claims.

What Sanders wants is a federally run program charged with providing health coverage to everyone. Private insurance companies wouldn’t participate.

In other words: single-payer, with the federal government at the helm.

Absent federal action, Democratic gubernatorial candidates Gavin Newsom in California, Jay Gonzales in Massachusetts and Andrew Gillum in Florida are pushing for state-run single-payer.

To complicate matters, some Democrats are simply calling for universal coverage, a vague philosophical idea subject to interpretation. Universal health care could mean a single-payer system, Medicare-for-all or building upon what exists today — a combination of public and private programs in which everyone has access to health care.

Others call for a “public option,” a government plan open to everyone, including Democratic House candidates Antonio Delgado in New York and Cindy Axne in Iowa. Delgado wants the public option to be Medicare, but Axne proposes Medicare or Medicaid.

Are you confused yet?

Sacramento-area voter Sarah Grace, who describes herself as politically independent, said the dialogue is over her head.

“I was a health care professional for so long, and I don’t even know,” said Grace, 42, who worked as a paramedic for 16 years and now owns a holistic healing business. “That’s telling.”

In fact, most voters approached for this article declined to be interviewed, saying they didn’t understand the issue. “I just don’t know enough,” Paul Her of Sacramento said candidly.

“You get all this conflicting information,” said Her, 32, a medical instrument technician who was touring the state Capitol with two uncles visiting from Thailand. “Half the time, I’m just confused.”

The confusion is all the more striking in a state where the expansion of coverage has dominated the political debate on and off for more than a decade. Although the issue clearly resonates with voters, the details of what might be done about it remain fuzzy.

A late-October poll by the Public Policy Institute of California shows the majority of Californians, nearly 60 percent, believe it is the responsibility of the federal government to make sure all Americans have health coverage. Other state and national surveys reveal that health care is one of the top concerns on voters’ minds this midterm election.

Democrats have seized on the issue, pounding GOP incumbents for voting last year to repeal the Affordable Care Act and attempting to water down protections for people with preexisting medical conditions in the process. A Texas lawsuit brought by 18 Republican state attorneys general and two GOP governors could decimate protections for preexisting conditions under the ACA — or kill the law itself.

Republicans say the current health care system is broken, and they have criticized the rising premiums that have hit many Americans under the ACA.

Whether the Democratic focus on health care translates into votes remains to be seen in the party’s drive to flip 23 seats to gain control of the House.

The Denham-Harder race is one of the most watched in the country, rated too close to call by most political analysts. Harder has aired blistering ads against Denham for his vote last year against the ACA, and he sought to distinguish himself from the incumbent by calling for Medicare-for-all — an issue he hopes will play well in a district where an estimated 146,000 people would lose coverage if the 2010 health law is overturned.

Yet Harder is not clinging to the Medicare-for-all label and said Democrats may need to talk more broadly about getting everyone health care coverage.

“I think there’s a spectrum of options that we can talk about,” Harder said. “I think the reality is we’ve got to keep all options open as we’re thinking towards what the next 50 years of American health care should look like.”

To some voters, what politicians call their plans is irrelevant. They just want reasonably priced coverage for everyone.

Sitting with his newspaper on the porch of a local coffee shop in Modesto, John Byron said he wants private health insurance companies out of the picture.

The 73-year-old retired grandfather said he has seen too many families struggle with their medical bills and believes a government-run system is the only way.

“I think it’s the most effective and affordable,” he said.

Linda Wahler of Santa Cruz, who drove to this Central Valley city to knock on doors for the Harder campaign, also thinks the government should play a larger role in providing coverage.

But unlike Byron, Wahler, 68, wants politicians to minimize confusion by better defining their health care pitches.

“I think we could use some more education in what it all means,” she said.

When HealthLeaders issued its first list in April of the healthcare leaders running for public office, there were more than 60 candidates with relevant healthcare backgrounds out on the campaign trail. Now, that list has nearly been halved, with 35 candidates still remaining.

This collection of healthcare leaders includes registered nurses, former insurance company executives, physicians, and former government health policy leaders.

In an election decidedly marked by voter interest on healthcare, these leaders are eyeing to shape policy by bringing their industry experience to both houses of Congress as well as the governor’s mansion in their respective states.

Check out the list below to see which healthcare players are running for office or reelection.

Gov. Rick Scott, R-Fla., is the Republican nominee in Senate race against Democratic incumbent Bill Nelson.

Scott founded Columbia Hospital Corporation, ultimately merging with Hospital Corporation of America in 1989 to form Columbia/HCA.

Scott resigned as CEO in 1997 over issues regarding Medicare billing practices by his organization.

Former Gov. Phil Bredesen, D-Tenn., is the Democratic nominee in Senate race to replace outgoing Republican incumbent Bob Corker.

Bredesen founded HealthAmerica Corp., an insurance company that he sold his controlling interest in 1986.

Bob Hugin, R-N.J., is the Republican nominee in Senate race against Democratic incumbent Bob Menendez.

Hugin is the former CEO of Celgene Corp.

State Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, R-W.V., is the Republican nominee in Senate race against Democratic incumbent Joe Manchin.

As partner at King & Spalding, Morrisey focused the majority of his work on healthcare legislation.

He served as both deputy staff director and chief health counsel for the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

State Sen. Leah Vukmir, R-Wisc., is the Republican nominee in Senate race against Democratic incumbent Tammy Baldwin.

Vukmir worked as a nurse.

Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wy., running for reelection.

Barrasso is an orthopedic surgeon.

Dr. Dawn Barlow, D-Tenn., is the Democratic nominee in House race to replace outgoing Republican incumbent Diane Black.

Barlow serves as director of hospital medicine at Livingston Regional Hospital.

Jim Maxwell, MD, R-N.Y., is the Republican nominee in House race to replace deceased Democratic incumbent Louise Slaughter.

Maxwell is a neurosurgeon affiliated with Rochester General Hospital.

Mel Hall, D-Ind., is the Democratic nominee in House race against Republican incumbent Jackie Walorski.

Hall formerly served as CEO of Press Ganey, a patient satisfaction firm.

Lauren Underwood, RN, D-Illi., is the Democratic nominee in House race against Republican incumbent Randy Hultgren.

Underwood is a registered nurse.

She also served as a senior advisor to the Department of Health and Human Services under President Barack Obama.

State Sen. Jeff Van Drew, D-N.J., is the Democratic nominee in House race to replace outgoing Republican incumbent Frank LoBiondo.

Van Drew is a dentist.

Dr. Hiral Tipirneni, D-Ariz., is the Democratic nominee in House race against Republican incumbent Debbie Lasko.

Former HHS Secretary Donna Shalala, D-Fla., is the Democratic nominee in House race to replace outgoing Republican incumbent Ileana Ros-Lehtinen.

Dr. Steve Ferrara, R-Ariz., is the Republican nominee in House race to replace outgoing Democratic incumbent Kyrsten Sinema.

Ferrara is an interventional radiologist.

Dr. Matt Longjohn, D-Mich., is the Democratic nominee in House race against Republican incumbent Fred Upton.

Longjohn is a physician.

He also served as the first National Health Officer for the YMCA.

Dr. Kim Schrier, D-Wash., is the Democratic nominee in House race to replace outgoing Republican incumbent Dave Reichert.

Schrier is a pediatrician.

Related: Collected Profiles of Healthcare Leaders Running in the Midterms

Rep. Brad Wenstrup, R-Ohio, running for reelection.

Wenstrup is a physician.

Rep. Scott DesJarlais, R-Tenn., running for reelection.

DesJarlais is a physician.

Rep. Michael Burgess, R-Texas, running for reelection.

Burgess is a physician.

Rep. Ami Bera, D-Calif., running for reelection.

Bera served as Chief Medical Officer of Sacramento County.

Rep. Neal Dunn, R-Fla., running for reelection.

Dunn is a surgeon.

Rep. Drew Ferguson, R-Ga., running for reelection.

Ferguson is a dentist.

Rep. Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, running for reelection.

Simpson is a dentist.

Rep. Larry Bucshon, R-In., running for reelection.

Buchson is a heart surgeon.

Rep. Roger Marshall, R-Kansas, running for reelection.

Marshall is an obstetrician.

Rep. Andy Harris, R-Md., running for reelection.

Harris is an anesthesiologist.

Rep. Phil Roe, R-Tenn., running for reelection.

Roe is an OB/GYN.

Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, D-Texas, running for reelection.

Johnson was the first nurse elected to Congress in 1993.

Rep. Raul Ruiz, D-Calif., running for reelection.

Ruiz is a physician.

Rep. Ralph Abraham, R-La., running for reelection.

Abraham is a physician.

Rep. Seth Moulton, D-Mass., running for reelection

Moulton founded Eastern Healthcare Partners in 2011.

Rep. Michelle Lujan Grisham, D-N.M., is the Democratic nominee in the gubernatorial race to replace outgoing Republican incumbent Susana Martinez.

Grisham previously served as head of the state’s Department of Health.

State Rep. Knute Buehler, R-Ore., is the Republican nominee in the gubernatorial race against Democratic incumbent Kate Brown.

Buehler works as an orthopedic surgeon at the Center for Orthopedic and Neurosurgical Care and Research.

He also serves as a member of the Board of Directors for the Ford Family Foundation and St. Charles Health System.

Gov. Charlie Baker, R-Mass., running for reelection.

Baker served in the state department of health and human services under two governors in the 1990s.

He also served as CEO of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates beginning in 1998.

Gov. Kim Reynolds, R-Iowa, running for reelection.

Reynolds worked as a pharmacist assistant

Issues to watch: Medicaid expansion in 4 states, a healthcare bond initiative in California, and the debate over preexisting condition protections.

Candidates to watch: Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, former Gov. Phil Bredesen, former HHS Secretary Donna Shalala, and others.

Healthcare has been an overarching issue for voters in the 2018 midterm election cycle, with many focusing on the future of the Affordable Care Act when it comes to national health policy but also taking stock of state and local ballot initiatives as well.

Several traditionally Republican states will decide whether to expand Medicaid under the ACA; staffing requirements for nurses are a hot-button topic in Massachusetts; and a major children’s hospital bond is on the table in California.

Beyond the issues are the candidates, including many Republican leaders on Capitol Hill in tight races to defend their seats after voting to repeal and replace the ACA. At the state level, Republican governors and their attorneys general are having their healthcare records put to the test as Democrats make protecting preexisting conditions and rejecting Medicaid work requirements key parts of the campaign.

Here are the key issues and candidates healthcare leaders will be watching as results begin rolling in Tuesday evening, with voters determining the direction of healthcare policymaking for years to come.

One year after voters approved Medicaid expansion in Maine, the first state to do so through a ballot initiative, four other states have the opportunity to join the Pine Tree State.

Montana: The push to extend Medicaid expansion in Montana before the legislative sunset at the end of the year is tied to another issue: a tobacco tax hike. The ballot measure, already the most expensive in Montana’s history, would levy an additional $2-per-pack tax on cigarettes to fund the Medicaid expansion which covers 100,000 persons.

Nebraska: Initiative 427 in traditionally conservative Nebraska, could extend Medicaid coverage to another 90,000 people. The legislation has been oft-discussed around the Cornhusker State, earning the endorsement of the Omaha World-Herald editorial board.

Idaho: Medicaid expansion has been one of the most talked about political items in Idaho throughout 2018. Nearly 62,000 Idahoans would be added to the program by Medicaid expansion, some rural hospitals have heralded the move as a financial lifeline, and outgoing Gov. Bruce Otter, a Republican, blessed the proposal last week.

Utah: Similar to Montana’s proposal, Utah’s opportunity to expand Medicaid in 2018 would be funded by a 0.15% increase to the state’s sales tax, excluding groceries. The measure could add about 150,000 people to Medicaid if approved by voters, who back the measure by nearly 60%, according to a recent Salt Lake Tribune/Hinckley Institute poll.

In addition to the four states considering whether to expand Medicaid, there are four others considering ballot initiatives that could significantly affect the business of healthcare.

Massachusetts mulls nurse staffing ratios. Question 1 would implement nurse-to-patient staffing ratios in hospitals and other healthcare settings, as Jennifer Thew, RN, wrote for HealthLeaders. The initiative has backing from the Massachusetts Nurses Association.

Nurses have been divided, however, on the question, and public polling prior to Election Day suggested a majority of voters would reject the measure, which hospital executives have actively opposed. The hospital industry reportedly had help from a major Democratic consulting firm.

California could float bonds for children’s hospitals. Proposition 4 would authorize $1.5 billion in bonds to fund capital improvement projects at California’s 13 children’s hospitals, as Ana B. Ibarra reported for Kaiser Health News. With interest, the measure would cost taxpayers $80 million per year for 35 years, a total of $2.9 billion, according to the state’s Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Proponents say children’s hospitals would be unable to afford needed upgrades without public assistance; opponents say the measure represents a fiscally unsound pattern. (California voters approved a $750 million bond in 2004 and a $980 million bond in 2008.)

Nevada nixing sales tax for medical equipment? Question 4 would amend the Nevada Constitution to require the state legislature to exempt certain durable medical goods, including oxygen delivery equipment and prescription mobility-enhancing equipment, from sales tax. The proposal, which passed a first time in 2016, would become law if it passes again.

Bennett Medical Services President Doug Bennett has been a key proponent of the measure, arguing that it would bring Nevada in line with other states, but opponents contend the measure is vaguely worded, as the Reno Gazette Journal reported.

Oklahoma weighs Walmart-backed optometry pitch. Question 793 would add a section to the Oklahoma Constitution giving optometrists and opticians the right to practice in retail mercantile establishments.

Walmart gave nearly $1 million in the third quarter alone to back a committee pushing for the measure. Those opposing the measure consist primarily of individual optometrists, as NewsOK.com reported.

It’s been more than two months since Republican attorneys general for 20 states asked a federal judge to impose a preliminary injunction blocking further enforcement of the Affordable Care Act, including its coverage protections for people with preexisting conditions. Some see the judge as likely to rule in favor of these plaintiffs, though an appeal of that decision is certain.

Amid the waiting game for the judge’s ruling, healthcare policymaking—especially as it pertains to preexisting conditions—rose to the top of voter consciousness in the midterms. That explains why some plaintiffs in the ACA challenge have claimed to support preexisting condition protections, despite pushing to overturn them.

The lawsuit and its implications mean healthcare leaders should be watching races in the 20 plaintiff states in the Texas v. Azar lawsuit: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine Gov. Paul LePage, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Thirteen of those plaintiff states have active elections involving their state attorneys general, and several have races for governor in which the ACA challenge has been an issue, including these noteworthy states:

Five states have received approvals from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to institute Medicaid work requirements: Kentucky, Indiana, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, and Arkansas. (Only four have active approvals, however, since a federal judge blocked Kentucky’s last summer.)

Three incumbent governors who pushed for work requirements are running for reelection:

New Hampshire: After receiving approval for New Hampshire’s Medicaid work requirements, Republican Gov. Chris Sununu said the government is committed to helping Granite Staters enter the workforce, adding that it is critical to the “economy as a whole.” Despite spearheading a controversial topic in a politically centrist state, Sununu has not trailed against his Democratic opponent Molly Kelly in any poll throughout the midterm elections.

Arkansas: Similarly, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, is running in a race where he has held a sizable lead over his Democratic challenger Jared Henderson. Since enacting the work requirements over the summer, the state has conducted two waves where it dropped more than 8,000 enrollees.

Wisconsin: The most vulnerable Republican governor of a state with approved Medicaid work requirements is Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, who has been neck and neck with Democratic nominee Tony Evers. While the Badger state only received approval for its Medicaid work requirements last week, healthcare has been a central issue of the campaign as Walker, a longtime opponent of the ACA, works to address premium costs in the state and defend his record on preexisting conditions.

Indiana and Kentucky: Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb and Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin are not on the ballot this year.

When HealthLeaders issued its first list in April of the healthcare leaders running for public office during the primaries, there were more than 60 candidates with relevant healthcare backgrounds out on the campaign trail.

Now, for the general election, that list has nearly been halved, with 35 candidates still remaining.

This collection of healthcare leaders includes registered nurses, former insurance company executives, physicians, and former government health policy leaders.

U.S. Senate: Running for the Senate are Florida Gov. Rick Scott, former Tennessee Gov. Phil Bredesen, former Celgene CEO Bob Hugin, and State Sen. Leah Vukmir.

U.S. House: Among those aiming to join the House are Lauren Underwood, RN, former HHS Secretary Donna Shalala, and Dr. Kim Schrier.

In race after race, Democrats have been pummeling Republicans on the most popular piece of Obamacare, protections for pre-existing conditions. No matter how sick someone might be, today’s law says insurance companies must cover them.

Republican efforts to repeal and replace Obamacare have all aimed to retain the guarantee that past health would be no bar to new coverage.

Democrats aren’t buying it.

In campaign ads in Nevada, Indiana, Florida, North Dakota, and more, Democrats charged their opponents with either nixing guaranteed coverage outright or putting those with pre-existing conditions at risk. The claims might exaggerate, but they all have had a dose of truth.

Republican proposals are not as air tight as Obamacare.

We’ll walk you through why.

In the old days, insurance companies had ways to avoid selling policies to people who were likely to cost more than insurers wanted to spend. They might deny them coverage outright, or exclude coverage for a known condition, or charge so much that insurance became unaffordable.

The Affordable Care Act boxes out the old insurance practices with a package of legal moves. First, it says point-blank that carriers “may not impose any preexisting condition exclusion.” It backs that up with another section that says they “may not establish rules for eligibility” based on health status, medical condition, claims experience or medical history.

Those two provisions apply to all plans. The third –– community rating –– targets insurance sold to individuals and small groups (about 7 percent of the total) and limits the factors that go into setting prices. In particular, while insurers can charge older people more, they can’t charge them more than three times what they charge a 21-year-old policy holder.

Wrapped around all that is a fourth measure that lists the essential health benefits that every plan, except grandfathered ones, must offer. A trip to the emergency room, surgery, maternity care and more all fall under this provision. This prevents insurers from discouraging people who might need expensive services by crafting plans that don’t offer them.

At rally after rally for Republicans, President Donald Trump has been telling voters “pre-existing conditions will always be taken care of by us.” At an event in Mississippi, he faulted Democrats, saying, “they have no plan,” which ignores that Democrats already voted for the Obamacare guarantees.

At different times last year, Trump voiced support for Republican bills to replace Obamacare. The White House said the House’s American Health Care Act “protects the most vulnerable Americans, including those with pre-existing conditions.” A fact sheet cited $120 billion for states to keep plans affordable, along with other facets in the bill.

But the protections in the GOP plans are not as strong as Obamacare. One independent analysis found that the bill left over 6 million people exposed to much higher premiums for at least one year. We’ll get to the congressional action next, but as things stand, the latest official move by the administration has been to agree that the guarantees in the Affordable Care Act should go. It said that in a Texas lawsuit tied to the individual mandate.

The individual mandate is the evil twin of guaranteed coverage. If companies were forced to cover everyone, the government would force everyone (with some exceptions) to have insurance, in order to balance out the sick with the healthy. In the 2017 tax cut law, Congress zeroed out the penalty for not having coverage. A few months later, a group of 20 states looked at that change and sued to overturn the entire law.

In particular, they argued that with a toothless mandate, the judge should terminate protections for pre-existing conditions.

The U.S. Justice Department agreed, writing in its filing “the individual mandate is not severable from the ACA’s guaranteed-issue and community-rating requirements.”

So, if the mandate goes, so does guaranteed-issue.

The judge has yet to rule.

In August, a group of 10 Republican senators introduced a bill with a title designed to neutralize criticism that Republicans don’t care about this issue. It’s called Ensuring Coverage for Patients with Pre-Existing Conditions. (A House Republican later introduced a similar bill.)

The legislation borrows words directly from the Affordable Care Act, saying insurers “may not establish rules for eligibility” based on health status, medical condition, claims experience or medical history.

But there’s an out.

The bill adds an option for companies to deny certain coverage if “it will not have the capacity to deliver services adequately.”

To Allison Hoffman, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, that’s a big loophole.

“Insurers could exclude someone’s preexisting conditions from coverage, even if they offered her a policy,” Hoffman said. “That fact alone sinks any claims that this law offers pre-existing condition protection.”

The limit here is that insurers must apply such a rule across the board to every employer and individual plan. They couldn’t cherry pick.

But the bill also gives companies broad leeway in setting premiums. While they can’t set rates based on health status, there’s no limit on how much premiums could vary based on other factors.

The Affordable Care Act had an outside limit of 3 to 1 based on age. That’s not in this bill. And Hoffman told us the flexibility doesn’t stop there.

“They could charge people in less healthy communities or occupations way more than others,” Hoffman said. “Just guaranteeing that everyone can get a policy has no meaning if the premiums are unaffordable for people more likely to need medical care.”

Rodney Whitlock, a health policy expert who worked for Republicans in Congress, told us those criticisms are valid.

“Insurers will use the rules available to them to take in more in premiums than they pay out in claims,” Whitlock said. “If you see a loophole and think insurers will use it, that’s probably true.”

Whitlock said more broadly that Republicans have struggled at every point to say they are providing the same level of protection as in the Affordable Care Act.

“And they are not,” Whitlock said. “It is 100 percent true that Republicans are not meeting the Affordable Care Act standard. And they are not trying to.”

The House American Health Care Act and the Senate Better Care Reconciliation Act allowed premiums to vary five fold, compared to the three fold limit in the Affordable Care Act. Both bills, and then later the Graham-Cassidy bill, included waivers or block grants that offered states wide latitude over rates.

Graham-Cassidy also gave states leeway to redefine the core benefits that every plan had to provide. Health law professor Wendy Netter Epstein at DePaul University said that could play out badly.

“It means that insurers could sell very bare-bones plans with low premiums that will be attractive to healthy people, and then the plans that provide the coverage that sicker people need will become very expensive,” Epstein said.

Insurance is always about sharing risk. Whether through premiums or taxes, healthy people cover the costs of taking care of sick people. Right now, Whitlock said, the political process is doing a poor job of resolving how that applies to the people most likely to need care.

“The Affordable Care Act set up a system where people without pre-existing conditions pay more to protect people who have them,” Whitlock said. “Somewhere between the Affordable Care Act standard and no protections at all is a legitimate debate about the right tradeoff. We are not engaged in that debate.”