Cartoon – Word of Mouth Marketing

Atrium Health struck out a year ago when it attempted to merge with in-state rival UNC Health Care, Bob reports. Now, the hospital system has inked a new deal to combine with Wake Forest Baptist Health, which is 90 minutes away from its headquarters.

Why it matters: Research overwhelmingly shows these kinds of regional hospital mergers lead to higher health care prices (and, consequently, premiums) because providers gain negotiating leverage and make it harder for health insurers to exclude them from networks.

Between the lines: The primary hook that Atrium and Wake Forest are selling is that they would build a new medical school in Charlotte. Because who could be against more doctors and research?

Sen. Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for All” plan would drastically change not only how health care is paid for, but who ultimately pays for it.

Driving the news: As part of yesterday’s rollout, Sanders released a white paper with several “options” on how to raise the additional revenue it would take for the government to pay for everyone’s health care without any premiums or out-of-pocket costs.

What they’re saying: Even if all of these payment options were implemented, they still wouldn’t cover the total cost of Sanders’ plan, said the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s Marc Goldwein.

The bottom line: “More progressive tax-based financing of health care is a feature, not a bug, of Medicare for all,” the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Larry Levitt said.

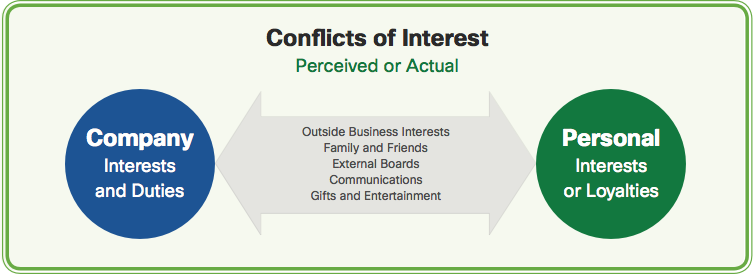

Chattanooga, Tenn.-based Erlanger Health System may have to upend its board of trustees if a bill targeting ties between governing bodies and public hospitals is signed into Tennessee law, according to the Times Free Press.

The bill, which passed the state’s Senate and is moving through its House, aims to protect consumers who live near a county or publicly owned hospital. It would prevent hospital authority trustees and former trustees from signing an employment agreement with an authority until at least 12 months after the trustee’s tenure of service on the board. The bill would not affect private or nonprofit hospitals.

The Times Free Press reviewed a list of current and former trustees from Erlanger to see if anyone would be affected by the bill. A hospital spokesperson told the publication “it would be premature for Erlanger to speculate who this bill impacts at this point.”

After reviewing conflict of interest disclosures trustees have to complete, the Times Free Press found current physician board members could have to choose between ending any financial ties with Erlanger or staying on the 11-member board.

Erangler’s Board Chairman Mike Griffin told the publication having physicians on the board is “a tremendous asset.” He added, “I am hopeful that the bill, in its final form, will not impact physician participation on Erlanger’s board.”

Citing a staff shortage, Los Angeles-based Pipeline Health announced plans April 9 to suspend services at Westlake Hospital in Melrose Park, Ill. That plan was put on hold after a Cook County Circuit Court judge held that the abrupt closure could have “irreparable harm” to the community, according to the Chicago Sun Times.

In late January, Pipeline acquired Westlake Hospital and two other facilities from Dallas-based Tenet Healthcare. A few weeks after the transaction closed, Pipeline revealed plans to shut down 230-bed Westlake Hospital, citing declining inpatient stays and losses of nearly $2 million a month.

Pipeline said staffing rates have significantly declined in the weeks since it filed the application to close Westlake Hospital.

“Our utmost priority is safety and quality of patient care,” Pipeline Health CEO Jim Edwards said in an April 9 press release. “With declining staffing rates and more attrition expected, a temporary suspension of services is necessary to assure safe and sufficient operations. This action is being taken after considering all alternatives and with the best interest of our patients in mind.”

In addition to announcing the suspension of services, Pipeline also said it gave hospital employees a 60-day notice of closure, which is required by state and federal law.

Pipeline’s plan to immediately suspend services at the hospital was put on hold yesterday evening, when Judge Eve Reilly granted the village of Melrose Park a temporary restraining order to prevent the hospital from closing. The restraining order prevents Pipeline from closing the hospital, cutting services or laying off workers until after the state Health Facilities and Services Review Board considers the application to shut down the hospital on April 30, according to the Chicago Tribune.

The board could postpone the application due a pending lawsuit against Pipeline over the closure, according to the Chicago Tribune.

The village of Melrose Park sued Pipeline in March, alleging Pipeline acquired Westlake Hospital under false pretenses. The lawsuit alleges Pipeline and its owners kept their plans to shut down the hospital secret until after the transaction with Tenet closed to avoid opposition from village leaders and community members.

Pipeline recently filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, arguing its application for change of ownership made no promise to keep Westlake Hospital open and that the hospital’s financial troubles were not fully evident at the time the change of ownership was prepared.

“The complete impact of Westlake’s 2018 devastating net operating loss was not known until the year’s end and had not fully occurred in September 2018 when Pipeline submitted its application for change of ownership or even when that application was granted,” Pipeline said in a press release.

Pipeline said Westlake Hospital ended 2018 with a net operating loss of $14 million, and those losses are projected to worsen over time.

Celina became the 11th rural hospital in Tennessee to close in recent years — more than in any state but Texas. Both states have refused to expand Medicaid in a way that covers more of the working poor.

The closest hospital is now 18 miles away. That adds another 30 minutes through mountain roads for those who need an X-ray or bloodwork. For those in the back of an ambulance, that bit of time could mean the difference between life or death.

When a rural community loses its hospital, health care becomes harder to come by in an instant. But a hospital closure also shocks a small town’s economy. It shuts down one of its largest employers. It scares off heavy industry that needs an emergency room nearby. And in one Tennessee town, a lost hospital means lost hope of attracting more retirees.

Seniors, and their retirement accounts, have been viewed as potential saviors for many rural economies trying to make up for lost jobs. But the epidemic of rural hospital closures is threatening those dreams in places like Celina, Tenn. The town of 1,500, whose 25-bed hospital closed March 1, has been trying to position itself as a retiree destination.

“I’d say, look elsewhere,” said Susan Scovel, a Seattle transplant who arrived with her husband in 2015.

Scovel’s despondence is especially noteworthy given she leads the local chamber of commerce effort to attract retirees like herself. She considers the wooded hills and secluded lake to hold scenic beauty comparable to the Washington coast — with dramatically lower costs of living; she and a small committee plan getaway weekends for prospects to visit.

When she first toured the region before moving in 2015, Scovel and her husband, who had Parkinson’s, made sure to scope out the hospital, on a hill overlooking the sleepy town square. And she has rushed to the hospital four times since he died in 2017.

“I have very high blood pressure, and they’re able to do the IVs to get it down,” Scovel said. “This is an anxiety thing since my husband died. So now — I don’t know.”

She can’t in good conscience advise a senior with health problems to come join her in Celina, she said.

When Seconds Count, Delays In Care

Celina’s Cumberland River Hospital had been on life support for years, operated by the city-owned medical center an hour away in Cookeville, which decided in late January to cut its losses after trying to find a buyer. Cookeville Regional Medical Center executives explain that the facility faced the grim reality for many rural providers.

“Unfortunately, many rural hospitals across the country are having a difficult time and facing the same challenges, like declining reimbursements and lower patient volumes, that Cumberland River Hospital has experienced,” CEO Paul Korth said in a written statement.

Celina became the 11th rural hospital in Tennessee to close in recent years — more than in any state but Texas. Both states have refused to expand Medicaid in a way that covers more of the working poor. Even some Republicans now say the decision to not expand Medicaid has added to the struggles of rural health care providers.

The closest hospital is now 18 miles away. That adds another 30 minutes through mountain roads for those who need an X-ray or bloodwork. For those in the back of an ambulance, that bit of time could mean the difference between life or death.

“We have the capability of doing a lot of advanced life support, but we’re not a hospital,” said Natalie Boone, Clay County’s emergency management director.

The area is already limited in its ambulance service, with two of its four trucks out of service.

Once a crew is dispatched, Boone said, it’s committed to that call. Adding an hour to the turnaround time means someone else could likely call with an emergency and be told — essentially — to wait in line.

“What happens when you have that patient that doesn’t have that extra time?” Boone asked. “I can think of at least a minimum of two patients [in the last month] that did not have that time.”

Residents are bracing for cascading effects. Susan Bailey hasn’t retired yet, but she’s close. She has spent nearly 40 years as a registered nurse, including her early career at Cumberland River.

“People say, ‘You probably just need to move or find another place to go,'” she said.

Bailey and others are concerned that losing the hospital will soon mean losing the only three physicians in town. The doctors say they plan to keep their practices going, but for how long? And what about when they retire?

“That’s a big problem,” Bailey said. “The doctors aren’t going to want to come in and open an office and have to drive 20 or 30 minutes to see their patients every single day.”

Closure of the hospital means 147 nurses, aides and clerical staff have to find new jobs. Some employees come to tears at the prospect of having to find work outside the county and are deeply sad that their hometown is losing one of its largest employers — second only to the local school system.

Dr. John McMichen is an emergency physician who would travel to Celina to work weekends at the ER and give the local doctors a break.

“I thought of Celina as maybe the ‘Andy Griffith Show’ of healthcare,” he said.

McMichen, who also worked at the now-shuttered Copper Basin Medical Center, on the other side of the state, said people at Cumberland River knew just about anyone who would walk through the door. That’s why it was attractive to retirees.

“It reminded me of a time long ago that has seemingly passed. I can’t say that it will ever come back,” he said. “I have hopes that there’s still some hope for small hospitals in that type of community. But I think the chances are becoming less of those community hospitals surviving.”

“UNFORTUNATELY, RURAL HOSPITALS ACROSS THE COUNTRY ARE HAVING A DIFFICULT TIME AND FACE THE SAME CHALLENGES, LIKE DECLINING REIMBURSEMENTS AND LOWER PATIENT VOLUMES THAT CUMBERLAND RIVER HOSPITAL HAS EXPERIENCED.”

The longtime CEO signaled in 2017, after a push for his ouster, that his likely successor would be recruited to the health system so he could retire.

The board decided keeping the same leader in place for another two years would be ‘our greatest advantage’ in the midst of change.

Eighteen months have passed since the medical executive committee of Willis-Knighton Health System in Shreveport, Louisiana, urged the board to force President and CEO James K. Elrod to either step out of his longtime leadership position voluntarily or be pushed.

The committee’s statement of no confidence in a letter to the trustees complained that Elrod failed to tolerate dissent and hadn’t responded appropriately to changes in the healthcare industry, as the Shreveport Times reported, describing the incident as “an attempted coup.”

Elrod was 80 at the time. He had worked for the organization more than 50 years and turned what was an 80-bed hospital into what became Louisiana’s largest health system. He weathered the criticism with backing from the board. Then he signaled in a letter to hospital staff that a succession planning process for his likely successor was underway.

Despite the controversy, the board announced Friday that it asked Elrod, now 81, to stay at his post for another two years.

“After taking some time to consider our vote, Mr. Elrod graciously agreed to delay his retirement plans,” board president Frank Hughes, MD, said in a statement describing Elrod as “our greatest advantage” in the face of uncertainty and change.

“This is a clear indication of his ongoing dedication and commitment to Willis-Knighton, and we are grateful for this decision,” Hughes added. “While we are pleased with the current senior leadership team assembled during the past 18 months, we felt that the greatest gift we could give them is additional time for mentoring and guidance. We made this decision in support of our physicians, our employees and the larger community.”

https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/feds-indict-24-massive-12b-telemarketing-dme-scheme

Two dozen people were indicted in the multistate, international telemarketing and DME scheme, which allegedly occurred in 17 federal judicial districts.

The 130 DME companies submitted more than $1.7 billion in claims to Medicare, were paid more than $900 million, and accounted in total for more than $1 billion in losses for the federal government.

The swindled money was allegedly laundered through international shell corporations and used to purchase exotic automobiles, yachts and luxury real estate in the United States and abroad,

Federal prosecutors are calling it one of the largest healthcare fraud schemes they’ve ever investigated.

Criminal indictments were made public this week against 24 people, including CEOs, COOs, physicians, and other executives at five telemedicine companies, and the owners of 130 durable medical equipment companies across 17 federal judicial districts for their roles in various schemes to bilk Medicare out of $1.2 billion.

Prosecutors said the DME companies allegedly paid kickbacks and bribes in exchange for the referral of Medicare beneficiaries by physicians in cahoots with fraudulent telemedicine companies for unnecessary back, shoulder, wrist and knee braces.

Some of the defendants allegedly controlled an international telemarketing network that lured over hundreds of thousands of elderly and/or disabled patients into a criminal scheme that crossed borders, involving call centers in the Philippines and throughout Latin America, prosecutors said.

The defendants allegedly paid doctors to prescribe DME either without any patient interaction or with only a brief telephonic conversation with patients they had never met or seen.

“The breadth of this nationwide conspiracy should be frightening to all who rely on some form of healthcare,” said Don Fort, Chief of Criminal Investigations at the Internal Revenue Service, one of six federal agencies involved in the probe.

“The conspiracy described in this indictment was not perpetrated by one individual. Rather, it details broad corruption, massive amounts of greed, and systemic flaws in our healthcare system that were exploited by the defendants,” Fort said.

The 130 DME companies submitted more than $1.7 billion in claims to Medicare and were paid more than $900 million, and accounted in total for more than $1 billion in losses for the federal government.

The swindled money was allegedly laundered through international shell corporations and used to purchase exotic automobiles, yachts and luxury real estate in the United States and abroad, prosecutors said.

Court documents allege that some of the defendants lured patients for the scheme by using an international call center that advertised to Medicare beneficiaries and “up-sold” the beneficiaries to get them to accept numerous “free or low-cost” DME braces, regardless of medical necessity.

The international call center allegedly paid illegal kickbacks and bribes to telemedicine companies to obtain DME orders for these Medicare beneficiaries. The telemedicine companies then allegedly paid physicians to write medically unnecessary DME orders. Finally, the international call center sold the DME orders that it obtained from the telemedicine companies to DME companies, which fraudulently billed Medicare.

Albert Davydov, 26, of Rego Park, New York, was charged for his alleged participation in a $35 million DME scheme.

Creaghan Harry, 51, of Highland Beach, Florida; Lester Stockett, 51, of Deefield Beach, Florida; and Elliot Loewenstern, 56, of Boca Raton, Florida; the owner, CEO and VP of marketing, respectively, of call centers and telemedicine companies were charged for their alleged participation in a $454 million kickback and money laundering scheme.

Joseph DeCoroso, MD, 62, of Toms River, New Jersey, was charged in a $13 million conspiracy to commit healthcare fraud and separate charges of healthcare fraud for writing medically unnecessary orders for DME, often without speaking to patients, while working for two telemedicine companies.