Cartoon – EMR’s have done Wonders for Patient Care

Health care executives gave no indication to bankers and investors at this year’s J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference that their pricing practices would change any time soon.

Why it matters: That sentiment comes the same week when three of the original authors of an influential 2003 article — which studied why health care is so expensive in the U.S.— published an update. Their conclusion was the same: “It’s still the prices, stupid.”

Though CFOs are usually known for their careful attention to detail, 48 percent of them have not identified a successor, according to a study in The Wall Street Journal.

Robert Half Management Resources surveyed 1,100 CFOs in various industries. Of those respondents who have not created a succession plan, nearly two-thirds said they had no plan because they did not intend to step down soon. They also cited the need to focus on other priorities and the absence of qualified candidates.

Jenna Fisher, head of the global corporate sector at executive search firm Russell Reynolds Associates, said the percentage of CFOs with succession plans represents a dramatic improvement from five years ago, when she estimated less than 10 percent of her clients had CFO succession plans.

“The role of CFO has become more salient,” Ms. Fisher said.

The appeals process to review a ruling that declared the entire Affordable Care Act invalid will have to wait until attorneys for the federal government have funding to proceed.

Fifth Circuit Court Judge Leslie H. Southwick issued a stay in the case Friday, granting a request filed earlier in the week by the U.S. Department of Justice.

The pause comes three weeks into a partial government shutdown that’s poised to become this weekend the longest in U.S. history, as President Donald Trump insists that Congress authorize $5.7 billion for a wall along the U.S. border with Mexico and Democrats refuse to do so.

While most of the federal government was funded by earlier legislation, this shutdown affects about 800,000 federal workers and inhibits the work of several agencies that handle health-related tasks.

Both the plaintiffs and federal defendants agreed that a stay would be appropriate. But the California-led coalition of Democratic state attorneys general challenging the lower court’s decision and the U.S. House of Representatives—which, newly under Democratic control, is seeking to intervene in the case to defend the ACA—opposed the stay request.

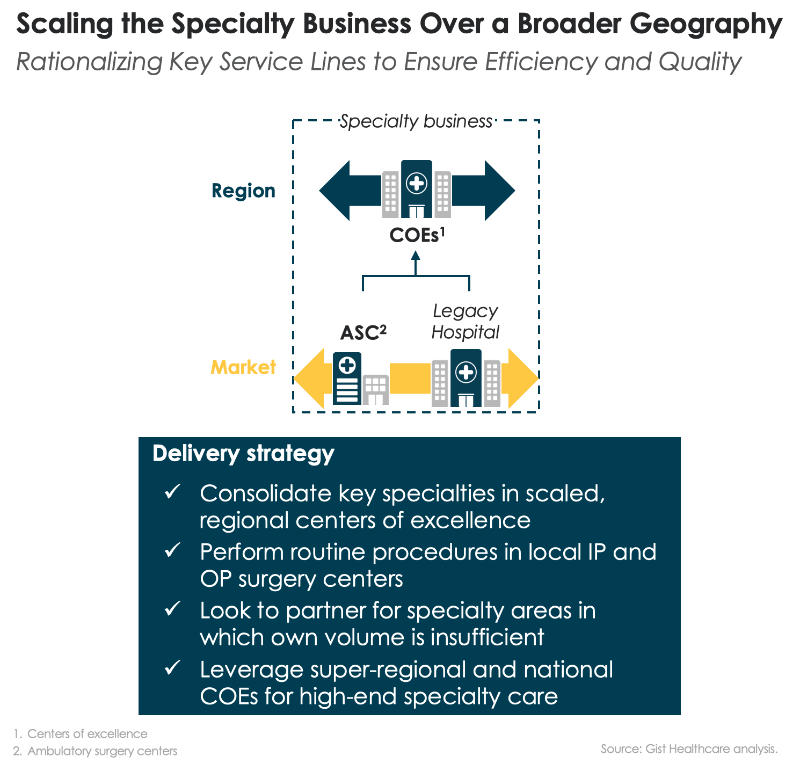

Over the past month we’ve been sharing our framework for helping health systems rethink their approach to investment in delivery assets, built around a functional view of the enterprise. We’ve encouraged providers to take a consumer-oriented approach to planning, starting by asking what consumers need and working backward to what services, programs and facilities are required to meet those needs. That led us to break the enterprise into component parts that perform different “jobs” for the people they serve. We think of each of those parts as a “business”, located at either the market, regional or national level depending on where the best returns to scale are found (and on the geographic scale of any particular system). So far we have described how a consumer-oriented health system should be organized at the market level, with expanded access and senior-care businesses providing lower-cost care in an outpatient setting for many services that were previously delivered in an acute-care hospital, and how the profile of the local hospital needs to change in response.

This week we shift our attention to health system services that can be scaled at the regional level, starting with specialty care, the medical and surgical specialty services that comprise many hospital service lines. Today nearly every community hospital is a “jack of all trades” with the same portfolio of services: obstetrics, cardiac care, orthopedics, and cancer care are the marquee service lines. Incentives, both market-based and internal to the health system, have encouraged this. Hospitals build services aimed at capturing the same handful of profitable (and usually procedurally-focused) DRGs. And many health systems reward local hospital leaders on the profitability of the hospitals they run, creating no incentive for those leaders to shift profitable volume to other hospitals in the system, and often resulting in redundant, inefficient, and sub-scale specialty care services.

We believe many specialty care services could be improved by moving care “up and out” of the community hospital. As we described before, a large portion of routine surgical care could be moved “out” of the hospital to lower-cost outpatient centers, supported by short-stay capabilities and expanded home health. At the same time, more complex specialty care should move “up” in the health system and be concentrated in regional “centers of excellence”, where expensive talent and expertise can be scaled, and systems can aggregate the volume needed for highly-efficient operations that lower the cost of delivering complex specialty care.

While the center of excellence model is not new, it’s often little more than a marketing slogan. Few systems have deployed it for operational efficiency, redirecting specialty care patients to high-volume-centers—and shuttering their low-volume or sub-standard local programs. Even fewer have invested in the infrastructure needed to effectively coordinate care between a regional center and local providers: telemedicine for effective provider collaboration and consultation, effective information sharing, and strong local care management support. One question inevitably arises: will patients travel for care? As individuals bear a larger portion of the cost of care, they do seem to be willing to travel longer distances in pursuit of better value. Understanding how the consumer “travel radius” changes with higher levels of financial accountability, and how that radius differs among services, ought to rank high on the priority list of systems looking to determine what business to consolidate at regional centers.

The selling spree is primarily meant to pay down the company’s outsized debt load left over from when Community Health was growing as fast as it could. But the hospital chain was also strategically pulling out of small towns, including several in Tennessee.

CEO Wayne Smith told investors gathered at this week’s annual J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco that it’s almost entirely left communities with fewer than 50,000 people — once its calling card compared to competing hospital chains.

“So our markets look a lot more like HCA and Universal and Tenet than they did in the past,” Smith said late Wednesday during a company presentation. “We’re no longer a non-urban, or for some of you all a rural, hospital company.”

As it’s repositioned, Community Health’s stock price tumbled to nearly two dollars a share, stoking concern of whether the company could even recover.

The hospital chain has continued to see shrinking admissions and ER visits, but executives assured investors this week they’ve regained their footing.

“Those divestitures have helped us in terms of paying down our debt, improving our margins, improving our cash flow, which you will see more of in 2019,” Smith said.

https://www.city-journal.org/de-blasios-health-care-for-all-illusion

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Tuesday a plan to “guarantee health care to all New Yorkers.” Responding to what he described as Washington’s failure to achieve single-payer health insurance, the mayor laid out a “transformative” plan to provide free, comprehensive primary and specialized care to 600,000 New Yorkers, including 300,000 illegal immigrants. “We are saying the word ‘guarantee’ because we can make it happen,” he announced, pledging to put $100 million toward the new initiative.

If spending an additional $100 million is all it takes to pay the health costs of a half-million people, you may wonder why New York City Health + Hospitals (HHC) is going broke spending $8 billion annually to treat 1.1 million people. The answer: Mayor de Blasio is not really proposing anything new; nor is he planning to expand services or care to anyone currently ineligible. All of New York City’s uninsured—including illegal aliens—can go to city hospitals and receive treatment on demand. The mayor is trying to do what some of his predecessors attempted—shift patients away from the emergency room and into primary care, or clinics. In 1995, for instance, then-mayor Rudy Giuliani empaneled a group of experts to address the future of the city’s public hospitals. The panel concluded, in the words of a Newsday editorial, that “for patients, emphasis would be on primary care instead of hurried emergency-room sessions and days of hospitalization.”

The tendency of a segment of the population to avoid the health-care system until a critical moment, relying in effect on emergency rooms for primary care, has been the knottiest problem in public health for decades. Letting simple problems fester makes them more expensive to treat. Using ERs designed to handle resource-intensive trauma situations for basic medical problems is inefficient and wasteful. The city has spent lots of money trying to convince poor, often dysfunctional people to develop regular medical habits by signing up for Medicaid and getting a primary-care doctor.

De Blasio makes it sound as though illegal immigrants have not been able to get health care until now. But in 2009, Alan Aviles, then the city’s hospitals chief, spoke of “hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funds that cover the costs of serving uninsured patients including undocumented immigrants.” Aviles said that the city was renowned for its “significant innovations in expanding access to care for immigrants, including our financial assistance policies that provide deeply discounted fees for the uninsured, our comprehensive communications assistance for limited English proficiency patients, and our strictly enforced confidentiality policies that afford new immigrants a sense of security in accessing needed care.”

In 2013, Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx announced a new “Integrated Wellness Program” targeting seriously mentally ill people with chronic health problems—the same population that tends to be uninsured, to neglect their own care, and to wind up in the emergency room when their diabetes or cardiovascular disease catches up with them. “At Lincoln, we aim to establish best practices that combine physical and mental health—two services which have historically been treated separately,” said Milton Nuñez, then as now Lincoln’s director—words not much different from what Chirlane McCray said at Tuesday’s “revolutionary” press conference.

HHC director Mitchell Katz practically admitted that the mayor’s announcement of guaranteed health care for all is just fanfare, amounting to more “enabling services” for already-existing programs. Asked if uninsured people—largely illegal immigrants—can get primary care now, Katz explained, “you can definitely walk into any emergency room, you can go to a clinic, but what is missing is the good customer service to ensure that you get an available appointment. . . . that’s what we’re missing and the mayor is providing.”

Dividing $100 million by 600,000 people comes to about $170 per person—perhaps enough money to cover one annual wellness visit to a nurse-practitioner, assuming no lab work, prescriptions, or illnesses. Clearly, the money that the mayor is assigning to this new initiative is intended for outreach—to convince people to go to the city’s already-burdened public clinics instead of waiting until they get sick enough to need an emergency room. That’s fine, as far as it goes, but as a transformative, revolutionary program, it resembles telling people to call the Housing Authority if they need an apartment and then pretending that the housing crisis has been solved. Mayor de Blasio is an expert at unveiling cloud-castles and proclaiming himself a master builder. His “health care for all” effort seems little different.

Healthcare Triage: Rural Hospital Closures Impact the Health of a Lot of People

Rural hospitals in the United States are having an increasingly hard time staying in business. Which is not great for the health of people who live in areas that no longer have a hospital.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin wrote for The Upshot. Links to sources can be found there.

https://www.axios.com/medicare-advantage-tilting-scales-7db28dd2-25af-4283-b971-21a61fa59371.html

Today is the final day when seniors and people with disabilities can sign up for Medicare plans for 2019, and consumer groups are concerned the Trump administration is steering people into privately run Medicare Advantage plans while giving short shrift to their limitations.

Between the lines: Medicare Advantage has been growing like gangbusters for years, and has garnered bipartisan support. But the Center for Medicare Advocacy says the Trump administration is tilting the scales by broadcasting information that “is incomplete and continues to promote certain options over others.”