https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/medicare-all-continuum

Several 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have called for “Medicare for All” as a way to expand health coverage and lower U.S. health care costs. Replacing most private insurance with a Medicare-like system for everyone has instilled both hope and fear across the country depending on people’s perspective or financial stake in the current health care system. But a closer look at recent congressional bills introduced by Democrats reveals a set of far more nuanced approaches to improving the nation’s health care system than the term Medicare for All suggests. To highlight these nuances, a new Commonwealth Fund interactive tool launched today illustrates the extent to which each of these reform bills would expand the public dimensions of our health insurance system, or those aspects regulated or run by state and federal government.1

The U.S Health Insurance System Is Both Public and Private

The U.S. health insurance system comprises both private (employer and individual market and marketplace plans) and public (Medicare and Medicaid) coverage sources, as the table below shows. In addition, both coverage sources are paid for by a mix of private and taxpayer-financed public dollars.

Most Americans get their insurance through employers, who either provide coverage through private insurers or self-insure. Employers and employees share the cost through premiums and cost-sharing such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. But the federal government significantly subsidizes employer coverage by excluding employer premium contributions from employees’ taxable income. In 2018 this subsidy amounted to $280 billion, the largest single tax expenditure.

About 27 million people are covered through regulated private plans sold in the individual market, including the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces. This coverage is financed by premiums and cost-sharing paid by enrollees. The federal government subsidizes these costs for individuals with incomes under $48,560.

For 44 million people, Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program is their primary source of coverage. These public programs are financed by federal and state governments, and small individual premium payments and cost-sharing in some states. In most states, these benefits are provided through private insurers.

Medicare covers 54 million people over age 65 and people with disabilities. The coverage is financed by the federal government along with individual premiums and significant cost-sharing. About 20 million people get their Medicare benefits through private Medicare Advantage plans and most beneficiaries either buy supplemental private insurance or qualify for additional coverage through Medicaid to help lower out-of-pocket costs and add long-term-care benefits.

Millions Still Uninsured or Underinsured, Health Care Costs High

The coverage expansions of the ACA — new regulation of private insurance such as requirements to cover preexisting conditions, subsidies for private coverage on the individual market, and expanded eligibility for Medicaid — lowered the number of uninsured people and made health coverage more affordable for many. But 28 million people remain uninsured and at least 44 million are underinsured. In addition, overall health care and prescription drug costs are much higher in the United States than in other wealthy countries. U.S. health care expenditures are projected to climb to nearly $6 trillion by 2027.

The Medicare for All Continuum

To address these problems, some Democrats running for president in 2020 are supporting Medicare for All. Meanwhile, in Congress, Democrats have introduced a handful of bills that might be characterized as falling along a continuum, with Medicare for All at one end.

As our new Commonwealth Fund interactive tool illustrates, the bills range from adding somewhat more public sector involvement into the system, to adding substantially more public sector involvement. The bills may be broadly grouped into three categories:

- Adding public plan features to private insurance. These include increasing regulation of private plans such as requiring private insurers who participate in Medicare and Medicaid to offer health plans in the ACA marketplaces, and enhancing federal subsidies for marketplace coverage.

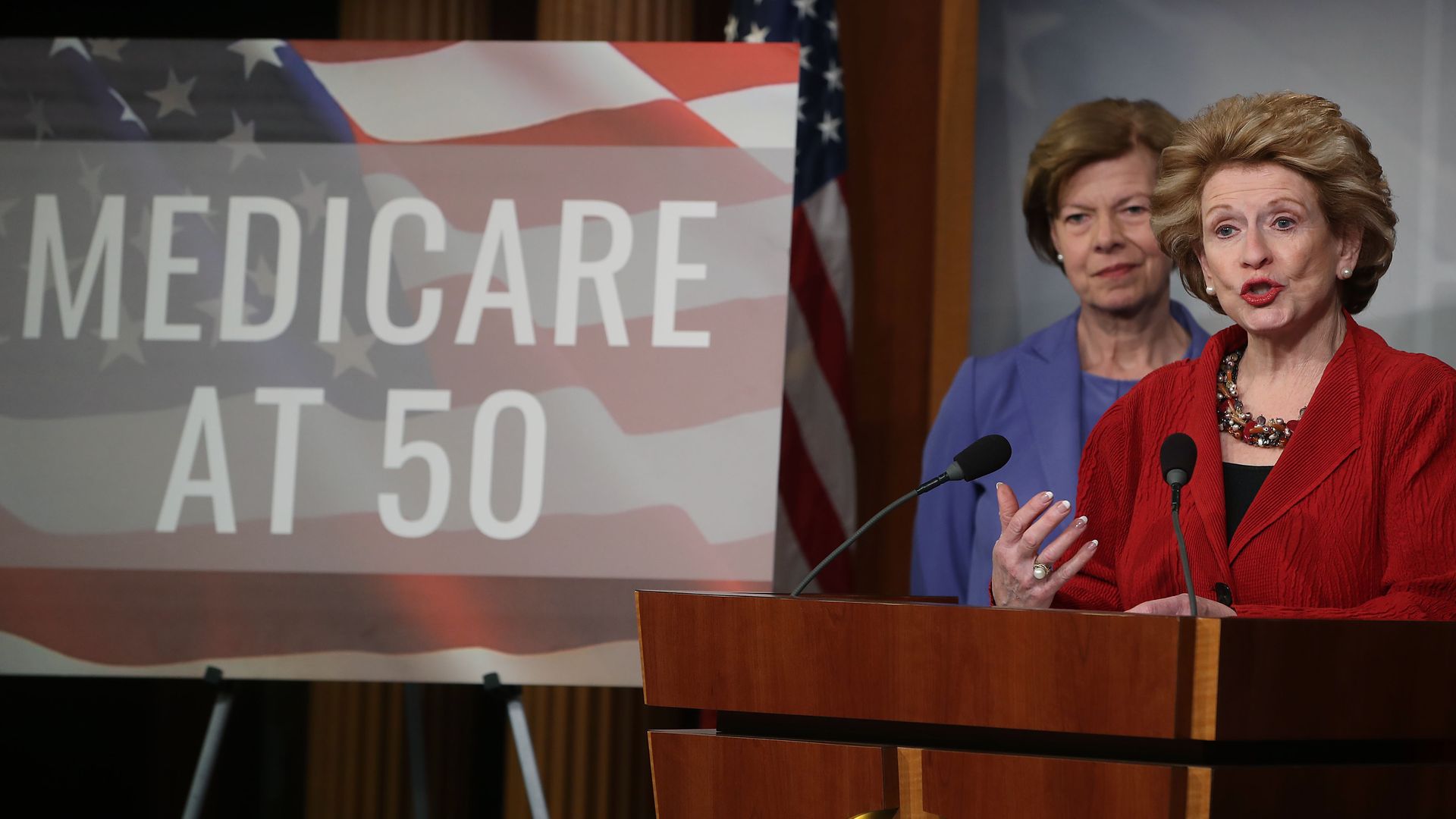

- Giving people a choice of public plans alongside private plans. These bills include offering a Medicare-like public plan option through the marketplaces, extending that option to employers to offer to their employees, giving people ages 50 to 64 the option to buy in to Medicare, and giving states the option to allow people to buy in to Medicaid. These bills also bring the federal government’s leverage into provider rate-setting and prescription drug price negotiation.

- Making public plans the primary source of coverage in the U.S. These are Medicare-for-All bills in which all residents are eligible for a public plan that resembles the current Medicare program, but isn’t necessarily the same Medicare program we have today. The bills vary by whether people would pay premiums and face cost-sharing, the degree to which they end current insurance programs and limit private insurance, how provider rates are set, whether global budgets are used for hospitals and nursing homes, and how long-term care is financed. All of the bills in this category allow people to purchase supplemental coverage for benefits not covered by the plan.

Looking Forward

Many Democratic candidates who have called for Medicare for All are cosponsors of more than one of these bills. The continuum of approaches suggests both the possibility of building toward a Medicare for All system over time, or adopting aspects of Medicare for All without the disruption that a major shift in coverage source might create for Americans. We will continue to update the tool as new bills are introduced or refined. Users also can view a comparison tool of other wealthy countries’ health systems, which shows where select countries fall on a continuum ranging from regulated systems of public and private coverage to national insurance programs.