https://hbr.org/2017/10/how-u-s-hospitals-and-health-systems-can-reverse-their-sliding-financial-performance

Since the beginning of 2016, the financial performance of hospitals and health systems in the United States has significantly worsened. This deterioration is striking because it is occurring at the top of an economic cycle with, as yet, no funding cuts from the Republican Congress.

The root cause is twofold: a mismatch between organizations’ strategies and actual market demand, and a lack of operational discipline. To be financially sustainable, hospitals and health systems must revamp their strategies and insist that their investments in new payment models and physician employees generate solid returns.

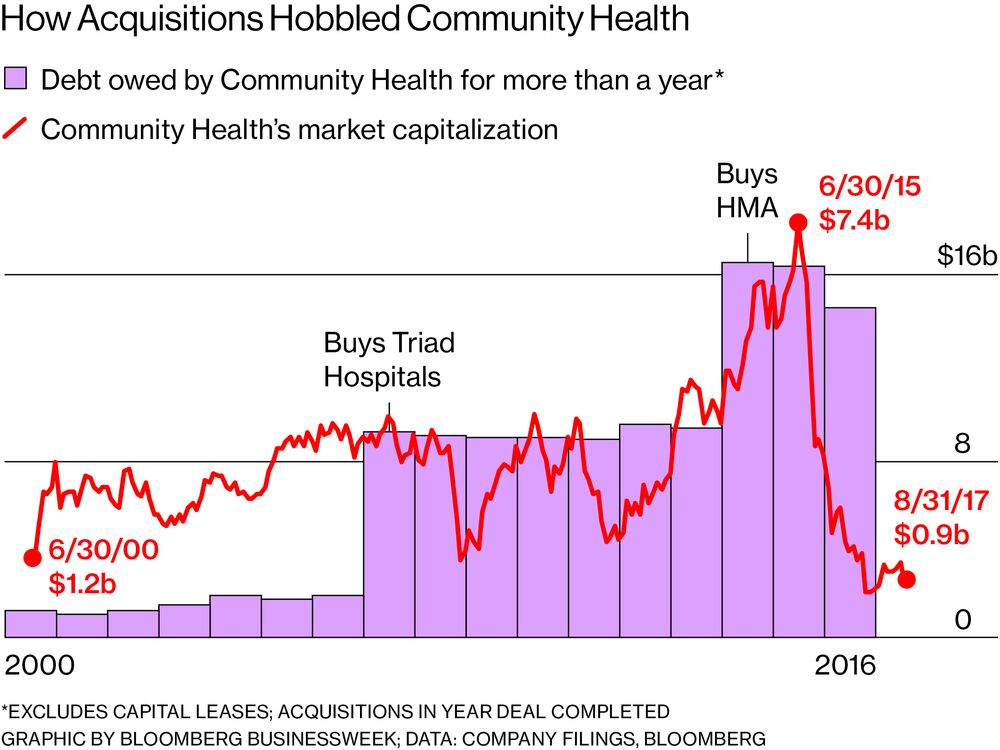

For the past decade, the consensus strategy among hospital and health-system leaders has been to achieve scale in regional markets via mergers and acquisitions, to make medical staffs employees, and to assume more financial risk in insurance contracts and sponsored health plans. In the past 18 months, the bill for this strategy has come due, posing serious financial challenges for many leading U.S. health systems.

MD Anderson Cancer Center lost $266 million on operations in FY 2016 and another $170 million in the first months of FY 2017. Prestigious Partners HealthCare in Boston lost $108 million on operations in FY 2016, its second operating loss in four years. The Cleveland Clinic suffered a 71% decline in its operating income in FY 2016.

On the Pacific Coast, Providence Health & Services, the nation’s second largest Catholic health system, suffered a $512 million drop in operating income and a $252 million operating loss in FY 2016. Two large chains — Catholic Health Initiatives and Dignity Health — saw comparably steep declines in operating income and announced merger plans. Regional powers such as California’s Sutter Health, New York’s NorthWell Health, and UnityPoint Health, which operates in Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin, reported sharply lower operating earnings in early 2017 despite their dominant positions in their markets.

While some of these financial problems can be traced to troubled IT installations or losses suffered by provider-sponsored health plans, all have a common foundation: Increases in operating expenses outpaced growth in revenues. After a modest surge in inpatient admissions from the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion in the fall of 2014, hospitals have settled in to a lengthy period of declining hospital admissions.

At the same time, hospitals have seen their prices growing at a slower rate than inflation. Revenues from private insurance have not fully offset the reductions in Medicare payments stemming from the Affordable Care Act and federal budget sequestration initiated in 2012. Many hospitals and health systems strove to gain market share at the expense of competitors by deeply discounting their rates for new “narrow network” health planstargeted at public and private health exchanges, enrollments from which have far underperformed expectations.

The main cause of the operating losses, however, has been organizations’ lack of discipline in managing the size of their workforces, which account for roughly half of all hospital expenses. Despite declining inpatient demand and modest outpatient growth, hospitals have added 540,000 workers in the past decade.

To achieve sustainable financial performance, health systems must match their strategy to the actual market demand. The following areas deserve special management attention.

The march toward risk. Most health system leaders believe that population-based payment is just around the corner and have invested billions of dollars in infrastructure getting ready for it. But for population-based payment to happen, health plans must be willing to pay hospitals a fixed percentage of their income from premiums rather than pay per admission or per procedure. Yet, according to the American Hospital Association, only 8% of hospitals reported any capitated payment in 2014 (the last year reported by the AHA) down from 12% in 2003.

Contrary to widely held belief, the market demand from health insurers for provider-based risk arrangements has not only been declining nationally but even fell in California where it all began more than two decades ago. This decline parallels the decline in HMO enrollment. Crucially, there is marked regional variation in the interest of insurers in passing premium risk to providers. In a 2016 American Medical Group Association survey, 64% of respondents indicated that either no or very limited commercial risk products were offered in their markets.

The same mismatch has plagued provider-sponsored health-plan offerings. Instead of asking whether there are unmet needs in their markets reachable by provider-sponsored insurance or what unique skills or competencies they can bring to the health benefits market, many health systems have simply assumed that their brands are attractive enough to float new, poorly configured insurance offerings.

Launching complex insurance products in the face of competition from well-entrenched Blue Cross plans with lavish reserves and powerful national firms like UnitedHealth Group, Kaiser, and Aetna is an extremely risky bet. Many hospital-sponsored plans have drowned rapidly in poor risks or failed to achieve their enrollment goals. A recent analysis for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation shows that only four of the 37 provider-sponsored health plans established since Obamacare was signed into law were profitable in 2015.

The regular Medicare and commercial business. Most hospitals are losing money on conventional fee-for-service Medicare patients because their incurred costs exceed Medicare’s fixed, per-admission, DRG payments. Moreover, there is widespread failure to manage basic revenue-cycle functions for commercial patients related to “revenue integrity” (having an appropriately documented, justifiable medical bill that can be collected), billing, and collection. All these problems contribute to diminished cash flows.

Physician employees. For many health care system, physician “integration” — making physicians employees of the system — seems to have become an end in itself. Yet many hospitals are losing upwards of $200,000 per physician per year with no obvious return on the investment.

Health systems should have a solid reason for making physicians their employees and then should stick to it. If the goal is control over hospital clinical processes and episode-related expenses, then the physician enterprise should be built around clinical process managers (emergency physicians, intensivists, and hospitalists). If the goal is control over geographies or increasing the loyalty of patients to the health care system, the physician enterprise should be built around primary care physicians and advanced-practice nurses, whose distribution is based on the demand in each geography. If the goal is achieving specialty excellence, it should be built around defensible clusters of subspecialty internal medicine and surgical practitioners in key service lines (e.g., cardiology, orthopedics, oncology).

To create value by employing physicians, health systems must actually manage their physicians’ practices. This means standardizing compensation and support staffing, centralizing revenue-cycle functions and the negotiations of health plan rates, and reducing needless variation in prescribing and diagnostic-testing patterns. Health system all too often neglect these key elements.

***

If health systems are to improve their financial performance, they must achieve both strategic and operational discipline. If they don’t, their current travails almost certainly will deepen.