https://theweek.com/articles/811962/impossibility-bipartisan-healthcare-compromise

If there’s one thing political centrists claim to value, it’s compromise. It’s “the way Washington is supposed to work,” writes Third Way’s Bill Schneider. “Centrists, or moderates, are really people who are willing to compromise,” The Moderate Voice‘s Robert Levine tells Vice.

What does this mean when it comes to health care and the developing lefty push for Medicare-for-all? The fresh new centrist health-care organization, the Partnership for America’s Health Care Future (PAHCF), says it is a “diverse, patient-focused coalition committed to pragmatic solutions to strengthen our nation’s health-care system.” In keeping with the moderate #brand, PAHCF may not support Medicare-for-all. But perhaps they might support a quarter-measure compromise, like allowing people under 65 to buy into Medicare?

Haha, of course not. Their offer is this: nothing.

Valuing compromise in itself in politics is actually a rather strange notion. It would make a lot more sense to determine the optimal policy structure through some kind of moral reasoning, and then work to obtain an outcome as close as possible to that. Compromise is necessary because of the anachronistic (and visibly malfunctioning) American constitutional system, but it is only good insofar as it avoids a breakdown of democratic functioning that would be even worse.

However, “moderation” is routinely not even that, but instead a cynical veneer over raw privilege and self-interest. The American health-care system, as I have written on many occasions, is a titanic maelstrom of waste, fraud, and outright predation — ripping off the American people to the tune of $1 trillion annually.

And so, Adam Cancryn reports on the centrist Democrats plotting with Big Medical to strangle the Medicare-for-all effort:

Deep-pocketed hospital, insurance, and other lobbies are plotting to crush progressives’ hopes of expanding the government’s role in health care once they take control of the House. The private-sector interests, backed in some cases by key Obama administration and Hillary Clinton campaign alumni, are now focused on beating back another prospective health-care overhaul, including plans that would allow people under 65 to buy into Medicare.

Behind the preposterously named “PAHCF” stands a huge complex of institutions that benefit from the wretched status quo. This includes the PhRMA drug lobby (Americans spend twice what comparable countries do on drugs, almost entirely because of price-gouging), the Federation of American Hospitals (Americans overpay on almost every medical procedure by roughly 2- to 10-fold), the American Medical Association (U.S. doctors, especially specialists, make far more than in comparable nations), America’s Health Insurance Plans, and BlueCross BlueShield (the cost of average employer-provided insurance for a family of four has increased by almost $5,000 since 2014, to $28,166).

The human carnage inflicted by this bloody quagmire of corruption and waste is nigh unimaginable. Perhaps 30,000 people die annually from lack of insurance, and 250,000 annually from medical error. America is a country where insurance can cost $24,000 before it covers anything, where doctors can conspire to attend each other’s surgeries so they can send pointless six-figure balance bills, where hospitals can charge the uninsured 10 times the actual cost of care, where gangster drug companies can buy up old patents and jack up the price by 57,500 percent, and on and on.

One might think this is all a bit risky. Wouldn’t it be more prudent to accept some sensible reforms, so these institutions don’t get completely driven out of business?

But wealthy elites almost never behave this way. John Kenneth Galbraith, explaining the French Revolution, once outlined one of the firmer rules of history: “People of privilege almost always prefer to risk total destruction rather than surrender any part of their privileges.” One reason is “the invariable feeling that privilege, however egregious, is a basic right. The sensitivity of the poor to injustice is a small thing as compared with that of the rich.”

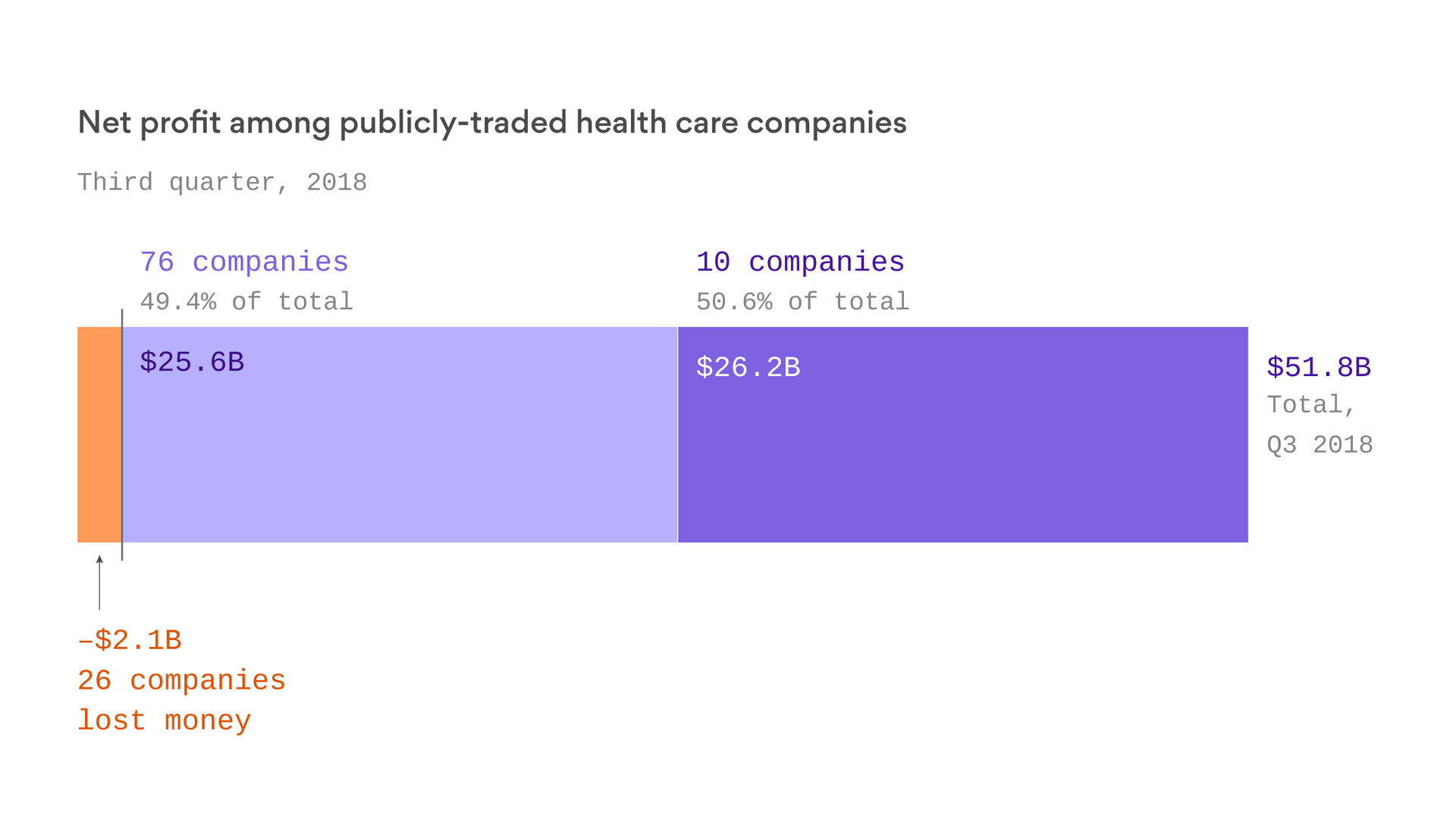

And so we see with the Big Medical lobby. The vast ziggurat of corpses piled up every year from horrific health-care dysfunction is just a minor side issue compared to the similar-sized piles of profits these companies accumulate — which they will fight like crazed badgers to preserve.

As Paul Waldman points out, this means a big resistance to the prospect of doing anything at all, let alone Medicare-for-all. However, the political implication is clear. If compromise is impossible, then liberals and leftists who want to improve the quality and justice of American health care should write off the corrupt pseudo-centrists, and go for broke. Democrats should write a health-care reform bill so aggressive that it drastically weakens the profitability of Big Medical, and drives many of them out of business entirely. If you cannot join them, beat them.