Category Archives: Ambulance

You might need an ambulance, but your state might not see it as ‘essential’

Ambulance services can receive state money once declared essential services.

When someone with a medical emergency calls 911, they expect an ambulance to show up.

But sometimes, there simply isn’t one available.

Most states don’t declare emergency medical services (EMS) to be an “essential service,” meaning the state government isn’t required to provide or fund them.

Now, though, a growing number of states are taking interest in recognizing ambulance services as essential — a long-awaited move for EMS agencies and professionals in the field, who say they hope to see more states follow through. Experts say the momentum might be driven by the pandemic, a decline in volunteerism and the rural health care shortage.

EMS professionals have been advocating for essential designation and more sustainable funding “for longer than I’ve been around — longer than I’ve been a paramedic,” said Mark McCulloch, 42, who is deputy chief of emergency medical services for West Des Moines, Iowa, and who has been a paramedic for more than two decades.

Currently, 13 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws designating or allowing local governments to deem EMS as an essential service, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, a think tank that has been tracking legislation around the issue.

Those include Connecticut, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Nebraska, Nevada, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia.

And at least two states — Massachusetts and New York — have pending legislation.

Idaho passed a resolution in March requiring the state’s health department to draft legislation for next year’s legislative session.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in Wyoming this summer rejected a bill that would have deemed EMS essential, according to local media.

“States have the authority to determine which services are essential, required to be provided to all citizens,” said Kelsie George, a policy specialist with the National Conference of State Legislatures’ health program.

Among those states deeming EMS as essential services, laws vary widely in how they provide funding. They might provide money to EMS services, establish minimum requirements for the agencies or offer guidance on organizing and paying for EMS services at the local level, George said.

The lack of EMS services is acute in rural America, where EMS agencies and rural hospitals continue to shutter at record rates, meaning longer distances to life-saving care.

“The fact that people expect it, but yet it’s not listed as an essential service in many states, and it’s not supported as such really, is where that dissonance occurs,” said longtime paramedic Brenden Hayden, chairperson of the National EMS Advisory Council, a governmental advisory group within the U.S. Department of Transportation.

More financial support

There isn’t a sole federal agency dedicated to overseeing or funding EMS, with multiple agencies handling different regulations, and some federal dollars in the form of grants and highway safety funds from the Department of Transportation. Medicaid and Medicare offer some reimbursements, but EMS advocates argue it isn’t nearly enough.

“It forces it as a state question, because the federal government has not taken on the authority to require it,” said Dia Gainor, executive director for the National Association of State EMS Officials and a former Idaho state EMS director. “It’s the prerogative of the state to make the choice” to mandate and fund EMS.

In states that don’t provide funding, EMS agencies often must rely on Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements and money they get from local governments.

Many of the latter don’t have the budgets to pay EMS workers, forcing poorer communities to turn to volunteers. But the firefighter and EMS volunteer pool is shrinking nationally as the volunteer force ages and fewer young people sign up.

Overhead for EMS agencies is expensive: A basic new ambulance can cost $200,000 to $300,000. Then there are the medicine and equipment costs, as well as staff wages and farther driving distances to medical centers in rural areas.

“The fact that people expect it, but yet it’s not listed as an essential service in many states, and it’s not supported as such really, is where that dissonance occurs.”

– Paramedic Brenden Hayden, chairperson of the National EMS Advisory Council

By contrast, police departments are supported and receive funds from the U.S. Department of Justice along with local tax dollars, and fire departments are supported by the U.S. Fire Administration, although many underserved areas also rely on volunteer firefighters to fill gaps.

“We need more if we’re going to save this industry and [if] we’re going to be available to treat patients,” Hayden said. “EMS in general represents a rounding error in the federal budget.”

What’s more, reimbursements only occur if a patient is taken to an emergency room. Agencies may not receive compensation if they stabilize a patient without transporting them to a hospital.

Gary Wingrove, president of the Paramedic Foundation, an advocacy group, has co-authored studies on the lack of ambulance service and on ambulance costs in rural areas. The former Minnesota EMS state director argues that reimbursements should be adjusted on a cost-based basis, like critical-access medical centers that serve high rates of uninsured patients and underresourced communities.

A rural crisis

About 4.5 million people across the United States live in an “ambulance desert,” and more than half of those are residents of rural counties, according to a recent national study by the Maine Rural Health Research Center and the Rural Health Research & Policy Centers. The researchers define an ambulance desert as a community 25 minutes or more from an ambulance station.

Some regions are more underserved than others: States in the South and the West have the most rural residents living in ambulance deserts, according to the researchers, who studied 41 states using data from 2021 and last year.

In South Dakota, the Rosebud Sioux Reservation covers a 1,900-square-mile area in the south-central part of the state.

State Rep. Eric Emery, a Democrat, is a paramedic and EMS director of the tribe’s sole ambulance station, providing services to 11,400 residents.

Emery and his colleagues respond to a variety of critical calls, from heart attacks to overdoses. They also provide care that people living on the reservation would otherwise get in the doctor’s office — if it didn’t take the whole day to travel to one. Those services might include taking blood pressure measurements, checking vital signs or making sure that a diabetic patient is taking their medicine properly.

Nevertheless, South Dakota is one of 37 states that doesn’t designate emergency medical services as essential, so the state isn’t required to provide or fund them.

While he and his staff are paid, remote parts of the reservation are often served by their respective county volunteer EMS agencies. It would simply take Emery’s crew too long — up to an hour — to arrive to a call.

“Something I wanted to tackle this year is to really look into making EMS an essential service here in South Dakota,” Emery said. “Being from such a conservative state that’s very conservative when it comes to their pocketbook, I know that’s probably going to be a really hard hill to climb.”

Ultimately, Wingrove said, officials need to value a profession that relies on volunteers to fill funding and staffing gaps.

“We’re looking for volunteers to make decisions about whether you live or die,” he said.

“Somehow, we have placed ourselves in a situation where the people that actually make those decisions are just not valued in the way they should be valued,” he said. “They’re not valued in the city budget, the county budget, the state budget, the federal budget system. They’re just not valued at all.”

Congress isn’t done with messy health care fights

https://www.axios.com/2022/08/17/congress-isnt-done-with-messy-health-care-fights

–

The Inflation Reduction Act is law. But that doesn’t mean major health care interests are done testing their lobbying clout. Many are already lining up for year-end relief from Medicare payment cuts, regulatory changes and inflation woes.

The big picture: Year-end spending bills often contain health care “extenders” that delay cuts to hospitals that treat the poorest patients or keep money flowing to community health centers. But lawmakers may be hard-pressed to justify the price tag this time, and are seeing an unusual assortment of appeals for help.

Background: 2% Medicare sequester cuts that had been paused by the pandemic took effect last month. Another 4% cut could come at year’s end, if lawmakers don’t delay it.

- These automatic reductions in spending come amid health labor force shortages, supply chain problems and other pressures that are making providers jockey for relief.

- It will fall to Congress to pick winners and losers among hospitals, physicians, home health care groups, nursing homes and ambulance services. And each says the consequences of not helping are dire.

- “The core question is how do they come up with the money and how do they decide to prioritize who give it to?” said Raymond James analyst Chris Meekins.

Go deeper: Hospitals are pressing hard for relief from the year-end sequester, and want Congress to extend or make permanent programs that support rural facilities and are slated to expire on Sept. 30, absent legislative action.

- The American Hospital Association has estimated its members will lose at least $3 billion by year’s end.

- Hospitals in the government’s discount drug program also have to be made whole after the Supreme Court unanimously overturned a huge pay cut stemming from a 2018 rule. And the industry also is seeking to reverse a planned cuts to supplementary payments for uncompensated care.

Doctors and nursing homes are among the other players lining up for relief from sequester cuts, specific Medicare payment changes that affect their businesses or new regulations.

- The American Medical Association says Medicare cuts could threaten physician practices that have been racked by pandemic-induced retirements and burnout. “This is really about allowing patients and Medicare beneficiaries to continue care,” AMA President Jack Resneck told Axios.

- National Association for Home Care and Hospice President Bill Dombi said over half of the home health agencies will run deficits if lawmakers don’t act. “When you have that many providers in the red, you can foresee there will be negative consequences. They’re already rejecting 20 to 30% of referrals for admissions to care, so it will be affecting patients,” said Dombi.

- Ambulance services are also struggling. “Ambulance providers around the country are at a very near breaking point as we kind of walk along the ledge leading to this cliff at the end of the calendar year,” Shawn Baird, president of the American Ambulance Association and chief operating officer of Metro West Ambulance in Oregon, told Axios.

The other side: Despite Congress’ willingness to delay payment cuts, there’s not enough money to make everyone happy. And concerns about Medicare program’s solvency that emerged during the lengthy debate over the Democrats’ tax, climate and health package could dampen lawmakers’ enthusiasm for costly fixes that favor one provider group.

- The continuation of the COVID-19 public health emergency and its myriad temporary payment allowances could also lessen a sense of urgency around provider relief.

The bottom line: For all the dire warnings, it’s unlikely Congress will do much until December, when it will likely pass a continuing resolution or an omnibus spending bill and could then move to delay the 4% cut.

Ambulance rides are getting a lot more expensive

The cost of an ambulance ride has soared over the past five years, according to a report from FAIR Health, shared first with Axios.

Why it matters: Patients typically have little ability to choose their ambulance provider, and often find themselves on the hook for hundreds, if not thousands of dollars.

The details: Most ambulance trips billed insurers for “advanced life support,” according to FAIR Health’s analysis.

- Private insurers’ average payment for those rides jumped by 56% between 2017 and 2020 — from $486 to $758.

- Ambulance operators’ sticker prices, before accounting for discounts negotiated with insurers, have risen 22% over the same period, and are now over $1,200.

Medicare, however, kept its payments in check: Its average reimbursement for advanced life support ambulance rides increased by just 5%, from $441 to $463.

Between the lines: Ambulances aren’t covered by the new law that bans most surprise medical bills, meaning patients are still on the hook in payment disputes between insurers and ambulance operators.

State of play: Ground ambulances are operated by local fire departments, private companies, hospitals and other providers and paid for in a variety of ways, which makes this a tricky issue to address, according to the Commonwealth Fund.

- Some states — such as Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New York, Ohio, Vermont and West Virginia — have protections against surprise ground ambulance billing, a columnist in the Deseret News pointed out earlier this year.

- But in California, Florida, Colorado, Texas, Illinois, Washington state and Wisconsin, more than two-thirds of emergency ambulance rides included an out-of-network charge for ambulance-related services that posed a surprise bill risk in 2018, according to a Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker brief.

- The Biden administration has said it’s working on the problem.

The bottom line: Costs for ground ambulance care are on the rise and, with few balance billing protections, that means patients could still be hit with some big surprises if they wind up needing a ride in an ambulance.

Setting the rules for settling “surprise bills”

https://mailchi.mp/a2cd96a48c9b/the-weekly-gist-october-1-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

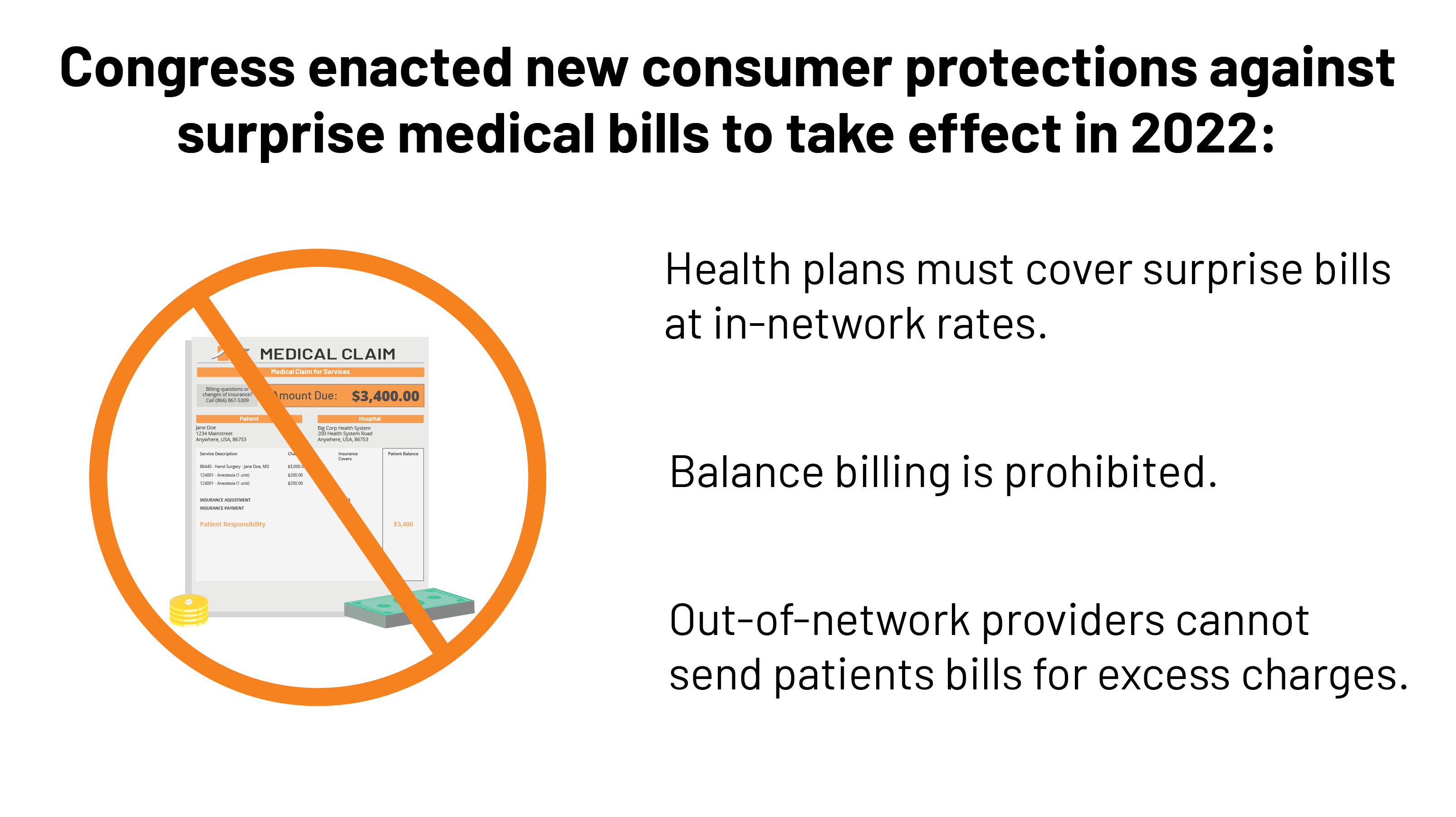

On Thursday the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), along with other federal agencies, released the long-awaited second half of its proposed regulations implementing the No Surprises Act, passed by Congress at the end of last year, which bans “surprise billing” of patients who unsuspectingly receive care from out-of-network providers.

The interim final rule, which will take effect on January 1st after a comment and review period, lays out a process for addressing disputed patient bills, first through a 30-day “open negotiation” between the patient’s insurer and the out-of-network provider, and then through a federally-managed arbitration process.

Of most interest to insurers and providers who have lobbied fiercely for months to ensure a favorable interpretation of the law, the new regulation specifies that the outsider arbitrator, to be agreed upon by both parties, must begin with the presumption that the median in-network rate for services in the local market is the correct one. The arbitrator can then modify that price based on the specific circumstances of the case.

That method was broadly favored by insurers, and AHIP strongly endorsed the proposed approach, saying in a press release that “this is the right approach to encourage hospitals, healthcare providers, and health insurance providers to work together and negotiate in good faith.” Predictably, the hospital lobby felt otherwise; the American Hospital Association reacted by calling the rule “a windfall for insurers”, saying that it “unfairly favors insurers to the detriment of hospitals and physicians who actually care for patients.”

The ultimate winners here are patients, who will gain important new protections against the potentially crippling financial implications of surprise billing. We’d agree with HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra, who told the New York Times that the new rule would “[take] patients out of the middle of the food fight,” and provide “a clear road map on how you can resolve that food fight between the provider and the insurer.” It’s about time.

Still unresolved: the high cost of out-of-network ambulance services, left out of the No Surprises Act altogether. Let’s hope Congress circles back to address that issue soon.

Sign of the Times (Medical Experts)

Biden administration begins to implement a ban on surprise bills

https://mailchi.mp/bfba3731d0e6/the-weekly-gist-july-2-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

On Thursday, the Biden administration issued the first of what is expected to be a series of new regulations aimed at implementing the No Surprises Act, passed by Congress last year and signed into law by President Trump, which bans so-called “surprise billing” by out-of-network providers involved in a patient’s in-network hospital visit.

The interim final rule, which takes effect in 2022, prohibits surprise billing of patients covered by employer-sponsored and individual marketplace plans, requiring providers to give advance warning if out-of-network physicians will be part of a patient’s care, limiting the amount of patient cost-sharing for bills issued by those providers, and prohibiting balance billing of patients for fees in excess of in-network reimbursement amounts.

The rule also establishes a process for determining allowable rates for out-of-network care, involving comparison to prevailing statewide rates or the involvement of a neutral arbitrator, but falls short of specifying a baseline price for arbitrators to use in determining allowable charges. That methodology, along with other details, will be part of future rulemaking, which will be issued later this year.

Of note, the rule does not include a ban on surprise billing for ground ambulance services, which were excluded by Congress in the law’s final passage—even though more than half of all ambulance trips result in an out-of-network bill. Expect intense lobbying by industry interests to continue as the details of future rulemaking are worked out, as has been the case since before the law was passed.

While burdensome for patients, surprise billing has become a lucrative business model for some large, investor-owned specialist groups, who will surely look to minimize the law’s impact on their profits.

Cartoon – Ambulance Service

Dubai’s Super-Ambulance Is a Mini Hospital-on-Wheels with an Operating Room and X-Ray Unit

Dubai is proud to introduce its impressive fleet of the “world’s largest ambulances,” or “Mercedes-Benz large-capacity ambulances” which were created to give rapid medical assistance in the event of major emergencies with large numbers of causalities. These new emergency vehicles offer a fully-equipped, mobile clinic with an intensive-care unit and an operating room.

Equipped with an X-ray unit and ultrasonic equipment for further evaluation, each super ambulance bus carries 12,000 liters of oxygen, which ensures a dependable supply for up to three days. With the press of a button, oxygen masks fall from special holders, and the oxygen flow to each mask can be individually controlled.

They’re also equipped with an ECG and an InSpectra shock monitor, which monitors the oxygen saturation in tissue-matter and warns doctors of the onset of shock minutes before it occurs. This unit can also detect and monitor internal bleeding. If an emergency caesarian birth is needed, essential obstetrical instruments, including an incubator, are on board.

Politicians Tackle Surprise Bills, but Not the Biggest Source of Them: Ambulances

A legislative push in Congress and states to end unexpected medical bills has omitted the ambulance industry.

After his son was hit by a car in San Francisco and taken away by ambulance, Karl Sporer was surprised to get a bill for $800.

Mr. Sporer had health insurance, which paid for part of the ride. But the ambulance provider felt that amount wasn’t enough, and billed the Sporer family for the balance.

“I paid it quickly,” Mr. Sporer said. “They go to collections if you don’t.”

That was 15 years ago, but ambulance companies around the nation are still sending such surprise bills to customers, as Mr. Sporer knows well. These days, he oversees the emergency medical services in neighboring Alameda County. The contract his county negotiated allows a private ambulance company to send similar bills to insured patients.

In most parts of medical care, you can choose a doctor or hospital that takes your insurance. But there are some types of care where politicians have begun tackling the “surprise” bills that occur when, say, patients go to an emergency room covered by their insurance and are treated by a physician who is not.

Five states have passed laws this year to restrict surprise billing in hospitals and doctor’s offices. Congress is working on a similar package of measures, after President Trump held a news conference in May urging action on the issue.

But none of these new policies will protect patients from surprise bills like the one Mr. Sporer received. Ordinary ambulances that travel on roads have been left out of every bill.

“Ambulances seem to be the worst example of surprise billing, given how often it occurs,” said Christopher Garmon, a health economist at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. “If you call 911 for an ambulance, it’s basically a coin flip whether or not that ambulance will be in or out of network.”

Mr. Garmon’s research finds that 51 percent of ground ambulance rides will result in an out-of-network bill. For emergency room visits, that figure stands at only 19 percent.

Congress has shown little appetite to include ambulances in a federal law restricting surprise billing. One proposal would bar surprise bills from air ambulances, helicopters that transport patients who are at remote sites or who have life-threatening injuries. (These types of ambulances tend to be run by private companies.)

But that interest has not extended to more traditional ambulance services — in part because many are run by local and municipal governments.

Lamar Alexander, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, and a key author of a Senate surprise billing proposal, said in an email that surprise bills from air ambulances were the more pressing issue because federal law prevents any local regulation of their prices. “Unlike air ambulances, ground ambulances can be regulated by states,” said Mr. Alexander, a Republican from Tennessee. “And Congress should continue to learn more about how to best solve that problem.”

The ambulance industry has brought its case to Capitol Hill, arranging meetings between members of Congress and their local ambulance operators.

“When we talk to our members of Congress, what we really emphasize is that we’re a little different from the other providers in the surprise billing discussion,” said Shawn Baird, president-elect of the American Ambulance Association. “We have a distinct, public process. The emergency room isn’t subject to any oversight of that kind.”

Patient advocates contend that this public oversight isn’t doing enough to protect patients, who often face surprise bills and forceful collection tactics from ambulance providers.

Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California, worked on a 2016 California law to restrict surprise billing. Initially, he thought it made sense to include ambulances in that legislation.

“It’s our experience that ambulance providers bill quicker and are more aggressive in sending bills to collection,” Mr. Wright said. “If they’re being more aggressive, you might want legislation to deal with that one first.”

But obstacles quickly began to mount. Some were about policy, like whether California would need to offset the revenue local governments would lose.

Then there were the politics. “There is the political reality that it’s hard to go after an entire industry at once,” Mr. Wright said. “It’s hard to have a bill opposed by doctors and hospitals and ambulances. We did manage to get a strong protection against doctor billing, but that was an epic, brutal, three-year fight.”

The California law that passed in 2016 did not regulate ambulance prices.

Patient groups elsewhere also say they ran into political trouble. Of the five states that passed surprise billing regulations in 2019, only Colorado’s new law takes aim at ambulance billing — not by regulating it, but by forming a committee to study the issue.

“The surprise bills laws are hard enough to get,” said Chuck Bell, program director for advocacy at Consumer Reports, who worked to pass a Florida surprise billing law in 2016. “You’re struggling with health plans, hospitals and doctors and other provider groups. At a certain point you don’t want to invite another big gorilla in the room to further widen the brawl.”

On Capitol Hill, the ambulance services have been less aggressive than other health care providers in lobbying against their inclusion in reforms. But lawmakers have largely declined to even include them in the conversation.

Consumer advocates say the lack of state-level legislation has been a barrier.

“Since there are issues related to ambulances being run by municipalities, and, at the state level, there hasn’t been a lot of model law to inform federal law, I think that’s made some members hesitant to wade into that space,” said Claire McAndrew, the director of campaigns and partnerships at the health care consumer group Families USA.

Local governments generally finance their ambulance services through a mix of user fees and taxes. If ambulances charge less to patients, they typically need more government funding.

Municipal governments often publish the prices of their ambulance services online, and they can range substantially. In Moraga and Orinda, in the Bay Area, the base rate for an ambulance ride is $2,600, plus $42 for each mile traveled. In Marion County, Fla., the most basic kind of ambulance ride costs $550, plus $11.25 per mile.

In many communities, there is no choice of ambulances.

Older patients are not charged such fees. Medicare, which also covers some people with disabilities, pays set prices for ambulance rides — a base rate of around $225 for the most typical type of care, in addition to a mileage fee — and forbids the companies to send patients additional bills.

In Bucks County, Pa., where it is $1,500 for a basic ambulance ride, in addition to $16 per mile, the emergency medical service gets 78 percent of its revenue from ambulance billing, according to Chuck Pressler, the executive director of the Central Bucks Emergency Medical Services. The rest of the budget comes from taxes raised by local cities and fund-raising drives.

“There is an expectation that we just plant money trees, that people should come in and work for free,” Mr. Pressler said of proposals to tamp down ambulance billing. “When was the last time you saw the police send out a fund-raiser? They don’t have to do that. Why do we have to raise money to come get you when you’re sick?”