https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/the-mu-variant-is-on-the-rise-scientists-weigh-in-on-how-much-to-worry?cmpid=org=ngp::mc=crm-email::src=ngp::cmp=editorial::add=SpecialEdition_20210910::rid=C1D3D2601560EDF454552B245D039020

Laboratory studies suggest this variant may be better at avoiding the immune system but lags Delta when it comes to transmission and infecting cells.

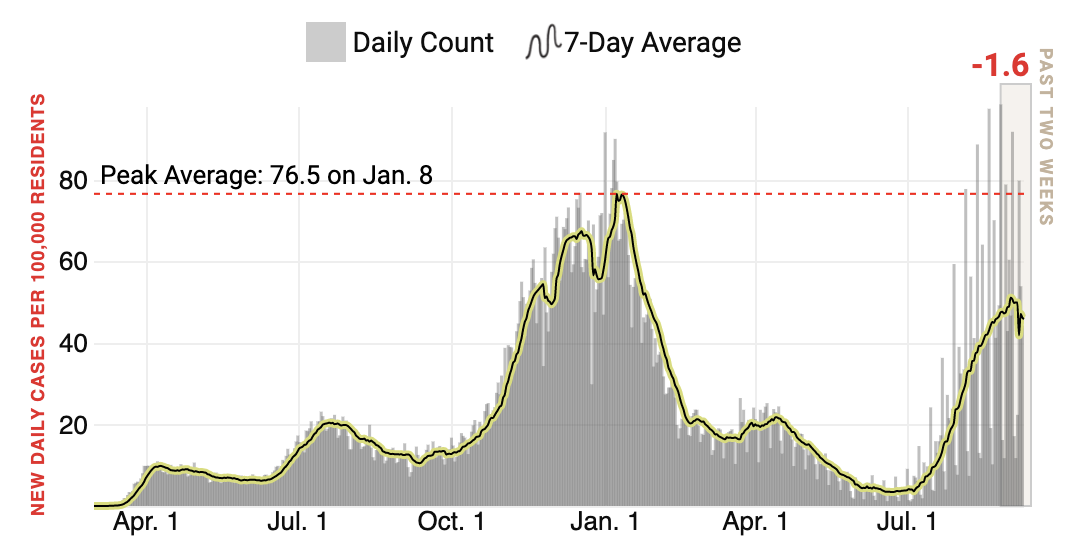

One of the newest variants of COVID-19, known as Mu, has spread to 42 countries, but early studies suggest that it is less easily transmitted than the dangerous Delta variant, which has triggered a resurgence of the pandemic in the U.S. and many other countries.

Mu quickly became the dominant strain in Colombia, where it was first detected in January, but in the U.S., where the Delta virus is dominant, it has not spread significantly. After reaching a peak at the end of June, the prevalence of the Mu variant in the U.S. has steadily declined.

Scientists believe that the new variant cannot compete with the Delta variant, which is highly contagious. “Whether it could have gone higher or not if there was no Delta, that’s hard to really say,” says Alex Bolze, a geneticist at the genomics company Helix.

In Colombia, however, the Mu variant is responsible for more than a third of the COVID-19 cases. There have been 11 noteworthy variants to date, which the World Health Organization has named for the letters of the Greek alphabet. The newest variant, Mu, is the 12th. WHO has labeled this latest version of SARS-CoV-2 a Variant of Interest, a step below a Variant of Concern.

Delta and three other variants have drawn the highest level of concern. But a Variant of Interest, like Mu still raises worries. Mu has many known mutations that can help the virus escape immunity from vaccines or previous infection.

Still, the good news is that Mu is unlikely to replace Delta in places like the U.S. where it is already predominant, says Tom Wenseleers, evolutionary biologist and biostatistician at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, who previously estimated the transmissibility and impact of Alpha variant in England.

How is Mu different?

Most genetic sequences reveal that Mu has eight mutations in its spike protein, many of which are also present in variants of concern: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta.

Some of Mu’s mutations, like E484K and N501Y, help other variants evade antibodies from mRNA vaccines. In the Beta and Gamma variants, the E484K mutation made the variants more resistant to a single dose of mRNA vaccines.

A study, not yet peer reviewed, has shown that the P681H mutation helps transmission of the Alpha variant—it may do the same for Mu.

Mu also harbors novel mutations that haven’t been seen in variants before, so their consequences are not fully understood. Mutation at the 346 position disrupts interaction of antibodies with the spike protein, which, scientists say, might make it easier for the virus to escape.

A study using epidemiological models, not yet peer reviewed, estimates that Mu is up to twice more transmissible than the original SARS-CoV-2 and caused the wave of COVID-19 deaths in Bogotá, Colombia in May, 2021. This study also suggests that immunity from a previous infection by the ancestral virus was 37 percent less effective in protecting against Mu.

“Right now, we do not have [enough] available evidence that may suggest that indeed this new variant Mu is associated with a significant [..] change in COVID,” says Alfonso Rodriguez-Morales, the President of the Colombian Association of Infectious Diseases.

But some clues are emerging that Mu can weaken protection from antibodies generated by existing vaccines. Lab-made virus mimicking the Mu variant were less affected by antibodies from people who had recovered from COVID-19 or were vaccinated with Pfizer’s Comiranty. In this study, not yet peer reviewed, Mu was the most vaccine resistant of all currently recognized variants.

In another lab-based study, antibodies from patients immunized with Pfizer’s vaccine were less effective at neutralizing Mu compared to other variants.

“[Mu] variant has a constellation of mutations that suggests that it would evade certain antibodies—not only monoclonal antibodies, but vaccine and convalescent serum-induced antibodies—but there isn’t a lot of clinical data to suggest that. It is mostly laboratory […] data,” said Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, at a White House press briefing on September 2.

The COVID-19 vaccines—Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Sinovac, all of which are available in Colombia—still seem to offer good protection against Mu, according to Rodriguez-Morales.

How prevalent is Mu?

The Mu variant rapidly expanded across South America, but it is difficult to know for sure how far Mu has spread, according to Paúl Cárdenas, microbiologist at Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador.

“[Latin American countries] have provided very low numbers of sequences, compared with the numbers of cases that we have,” says Cárdenas. South American countries have sequenced just 0.07 percent of their total SARS-CoV-2 positive cases, although 25 percent of global infections have occurred in the region. This contrasts with 1.5 percent of all positive cases sequenced in the U.S. and 9.3 percent of all positive cases sequenced in the U.K.

“We are not necessarily looking at the reality of the distribution of the variants [in Latin America], because of the limitations in performing genome sequencing,” says Rodriguez-Morales.

That said, except in Columbia where Mu has been spreading since late February, the variant is becoming relatively less frequent globally, including in the rest of South America.

“Additional evidence on Mu is scarce, similar to Lambda and other regionally prevalent variants, because of limited capacity for follow-up studies, and because these variants have not yet been a significant threat in high-income countries like Delta is,” says Pablo Tsukayama, a microbiologist at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Lima, Peru. He hopes the WHO’s designation of Mu as a variant of interest will change that.