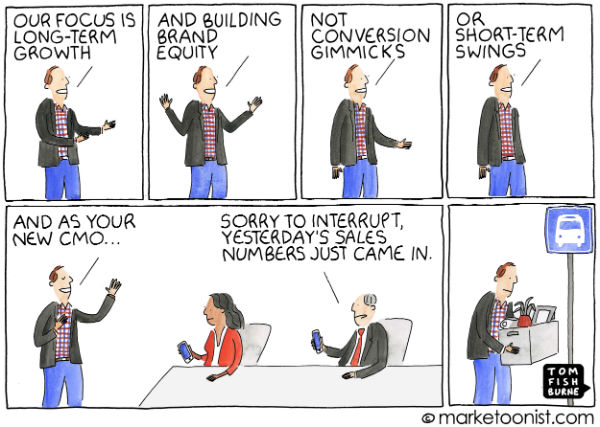

Cartoon – Fiscal Year Projections

Experts said the new data suggest that cases could soar in many U.S. communities if schools reopen soon.

Among the most important unanswered questions about Covid-19 is this: What role do children play in keeping the pandemic going?

Fewer children seem to get infected by the coronavirus than adults, and most of those who do have mild symptoms, if any. But do they pass the virus on to adults and continue the chain of transmission?

The answer is key to deciding whether and when to reopen schools, a step that President Trump urged states to consider before the summer.

Two new studies offer compelling evidence that children can transmit the virus. Neither proved it, but the evidence was strong enough to suggest that schools should be kept closed for now, many epidemiologists who were not involved in the research said.

Many other countries, including Israel, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have all either reopened schools or are considering doing so in the next few weeks.

In some of those countries, the rate of community transmission is low enough to take the risk. But in others, including the United States, reopening schools may nudge the epidemic’s reproduction number — the number of new infections estimated to stem from a single case, commonly referred to as R0 — to dangerous levels, epidemiologists warned after reviewing the results from the new studies.

In one study, published last week in the journal Science, a team analyzed data from two cities in China — Wuhan, where the virus first emerged, and Shanghai — and found that children were about a third as susceptible to coronavirus infection as adults were. But when schools were open, they found, children had about three times as many contacts as adults, and three times as many opportunities to become infected, essentially evening out their risk.

Based on their data, the researchers estimated that closing schools is not enough on its own to stop an outbreak, but it can reduce the surge by about 40 to 60 percent and slow the epidemic’s course.

“My simulation shows that yes, if you reopen the schools, you’ll see a big increase in the reproduction number, which is exactly what you don’t want,” said Marco Ajelli, a mathematical epidemiologist who did the work while at the Bruno Kessler Foundation in Trento, Italy.

The second study, by a group of German researchers, was more straightforward. The team tested children and adults and found that children who test positive harbor just as much virus as adults do — sometimes more — and so, presumably, are just as infectious.

“Are any of these studies definitive? The answer is ‘No, of course not,’” said Jeffrey Shaman, an epidemiologist at Columbia University who was not involved in either study. But, he said, “to open schools because of some uninvestigated notion that children aren’t really involved in this, that would be a very foolish thing.”

The German study was led by Christian Drosten, a virologist who has ascended to something like celebrity status in recent months for his candid and clear commentary on the pandemic. Dr. Drosten leads a large virology lab in Berlin that has tested about 60,000 people for the coronavirus. Consistent with other studies, he and his colleagues found many more infected adults than children.

The team also analyzed a group of 47 infected children between ages 1 and 11. Fifteen of them had an underlying condition or were hospitalized, but the remaining were mostly free of symptoms. The children who were asymptomatic had viral loads that were just as high or higher than the symptomatic children or adults.

“In this cloud of children, there are these few children that have a virus concentration that is sky-high,” Dr. Drosten said.

He noted that there is a significant body of work suggesting that a person’s viral load tracks closely with their infectiousness. “So I’m a bit reluctant to happily recommend to politicians that we can now reopen day cares and schools.”

Dr. Drosten said he posted his study on his lab’s website ahead of its peer review because of the ongoing discussion about schools in Germany.

Many statisticians contacted him via Twitter suggesting one or another more sophisticated analysis. His team applied the suggestions, Dr. Drosten said, and even invited one of the statisticians to collaborate.

“But the message of the paper is really unchanged by any type of more sophisticated statistical analysis,” he said. For the United States to even consider reopening schools, he said, “I think it’s way too early.”

In the China study, the researchers created a contact matrix of 636 people in Wuhan and 557 people in Shanghai. They called each of these people and asked them to recall everyone they’d had contact with the day before the call.

They defined a contact as either an in-person conversation involving three or more words or physical touch such as a handshake, and asked for the age of each contact as well as the relationship to the survey participant.

Comparing the lockdown with a baseline survey from Shanghai in 2018, they found that the number of contacts during the lockdown decreased by about a factor of seven in Wuhan and eight in Shanghai.

“There was a huge decrease in the number of contacts,” Dr. Ajelli said. “In both of those places, that explains why the epidemic came under control.”

The researchers also had access to a rich data set from Hunan province’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Officials in the province traced 7,000 contacts of 137 confirmed cases, observed them over 14 days and tested them for coronavirus infection. They had information not just for people who became ill, but for those who became infected and remained asymptomatic, and for anyone who remained virus-free.

Data from hospitals or from households tend to focus only on people who are symptomatic or severely ill, Dr. Ajelli noted. “This kind of data is better.”

The researchers stratified the data from these contacts by age and found that children between the ages of 0 and 14 years are about a third less susceptible to coronavirus infection than those ages 15 to 64, and adults 65 or older are more susceptible by about 50 percent.

They also estimated that closing schools can lower the reproduction number — again, the estimate of the number of infections tied to a single case — by about 0.3; an epidemic starts to grow exponentially once this metric tops 1.

In many parts of the United States, the number is already hovering around 0.8, Dr. Ajelli said. “If you’re so close to the threshold, an addition of 0.3 can be devastating.”

However, some other experts noted that keeping schools closed indefinitely is not just impractical, but may do lasting harm to children.

Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, said the decision to reopen schools cannot be made based solely on trying to prevent transmission.

“I think we have to take a holistic view of the impact of school closures on kids and our families,” Dr. Nuzzo said. “I do worry at some point, the accumulated harms from the measures may exceed the harm to the kids from the virus.”

E-learning approaches may temporarily provide children with a routine, “but any parent will tell you it’s not really learning,” she said. Children are known to backslide during the summer months, and adding several more months to that might permanently hurt them, and particularly those who are already struggling.

Children also need the social aspects of school, and for some children, home may not even be a safe place, she said.

“I’m not saying we need to absolutely rip off the Band-aid and reopen schools tomorrow,” she said, “but we have to consider these other endpoints.”

Dr. Nuzzo also pointed to a study in the Netherlands, conducted by the Dutch government, which concluded that “patients under 20 years play a much smaller role in the spread than adults and the elderly.”

But other experts said that study was not well designed because it looked at household transmission. Unless the scientists deliberately tested everyone, they would have noticed and tested only more severe infections — which tend to be among adults, said Bill Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“Assumptions that children are not involved in the epidemiology, because they do not have severe illness, are exactly the kind of assumption that you really, really need to question in the face of a pandemic,” Dr. Hanage said. “Because if it’s wrong, it has really pretty disastrous consequences.”

A new study by the National Institutes of Health may help provide more information to guide decisions in the United States. The project, called Heros, will follow 6,000 people from 2,000 families and collect information on which children get infected with the virus and whether they pass it on to other family members.

The experts all agreed on one thing: that governments should hold active discussions on what reopening schools looks like. Students could be scheduled to come to school on different days to reduce the number of people in the building at one time, for example; desks could be placed six feet apart; and schools could avoid having students gather in large groups.

Teachers with underlying health conditions or of advanced age should be allowed to opt out and given alternative jobs outside the classroom, if possible, Dr. Nuzzo said, and children with underlying conditions should continue to learn from home.

The leaders of the two new studies, Dr. Drosten and Dr. Ajelli, were both more circumspect, saying their role is merely to provide the data that governments can use to make policies.

“I’m somehow the bringer of the bad news but I can’t change the news,” Dr. Drosten said. “It’s in the data.”

Once the system can discriminate on a multitude of data points, the commons collapses.

A theme of my writing over the past ten or so years has been the role of data in society. I tend to frame that role anthropologically: How have we adapted to this new element in our society? What tools and social structures have we created in response to its emergence as a currency in our world? How have power structures shifted as a result?

Increasingly, I’ve been worrying a hypothesis: Like a city built over generations without central planning or consideration for much more than fundamental capitalistic values, we’ve architected an ecosystem around data that is not only dysfunctional, it’s possibly antithetical to the core values of democratic society. Houston, it seems, we really do have a problem.

Last week ProPublica published a story titled Health Insurers Are Vacuuming Up Details About You — And It Could Raise Your Rates. It’s the second in an ongoing series the investigative unit is doing on the role of data in healthcare. I’ve been watching this story develop for years, and ProPublica’s piece does a nice job of framing the issue. It envisions “a future in which everything you do — the things you buy, the food you eat, the time you spend watching TV — may help determine how much you pay for health insurance.”

Unsurprisingly, the health industry has developed an insatiable appetite for personal data about the individuals it covers. Over the past decade or so, all of our quotidian activities (and far more) have been turned into data, and that data can and is being sold to the insurance industry:

“The companies are tracking your race, education level, TV habits, marital status, net worth. They’re collecting what you post on social media, whether you’re behind on your bills, what you order online. Then they feed this information into complicated computer algorithms that spit out predictions about how much your health care could cost them.”

HIPPA, the regulatory framework governing health information in the United States, only covers and protects medical data – not search histories, streaming usage, or grocery loyalty data. But if you think your search, video, and food choices aren’t related to health, well, let’s just say your insurance company begs to differ.

Lest we dive into a rabbit hole about the corrosive combination of healthcare profit margins with personal data (ProPublica’s story does a fine job of that anyway), I want to pull back and think about what’s really going on here.

The Tragedy of the Commons

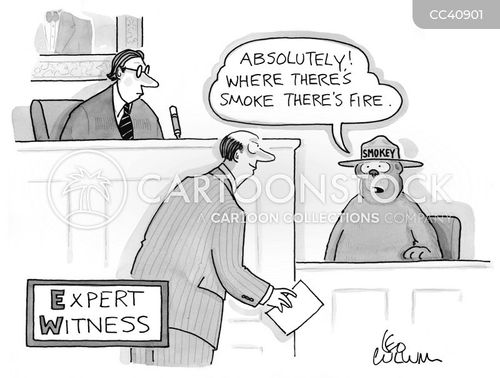

One of the most fundamental tensions in an open society is the potential misuse of resources held “in common” – resources to which all individuals have access. Garrett Hardin’s 1968 essay on the subject, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” explores this tension, concluding that the problem of human overpopulation has no technical solution. (A technical solution is one that does not require a shift in human values or morality (IE, a political solution), but rather can be fixed by application of science and/or engineering.) Hardin’s essay has become one of the most cited works in social science – the tragedy of the commons is a facile concept that applies to countless problems across society.

In the essay, Hardin employs a simple example of a common grazing pasture, open to all who own livestock. The pasture, of course, can only support a finite number of cattle. But as Hardin argues, cattle owners are financially motivated to graze as many cattle as they possibly can, driving the number of grass munchers beyond the land’s capacity, ultimately destroying the commons. “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all,” he concludes, delivering an intellectual middle finger to Smith’s “invisible hand” in the process.

So what does this have to do with healthcare, data, and the insurance industry? Well, consider how the insurance industry prices its policies. Insurance has always been a data-driven business – it’s driven by actuarial risk assessment, a statistical method that predicts the probability of a certain event happening. Creating and refining these risk assessments lies at the heart of the insurance industry, and until recently, the amount of data informing actuarial models has been staggeringly slight. Age, location, and tobacco use are pretty much how policies are priced under Obamacare, for example. Given this paucity, one might argue that it’s utterly a *good* thing that the insurance industry is beefing up its databases. Right?

Perhaps not. When a population is aggregated on high-level data points like age and location, we’re essentially being judged on a simple shared commons – all 18 year olds who live in Los Angeles are being treated essentially the same, regardless if one person has a lurking gene for cancer and another will live without health complications for decades. In essence, we’re sharing the load of public health in common – evening out the societal costs in the process.

But once the system can discriminate on a multitude of data points, the commons collapses, devolving into a system rewarding whoever has the most profitable profile. That 18-year old with flawless genes, the right zip code, an enviable inheritance, and all the right social media habits will pay next to nothing for health insurance. But the 18 year old with a mutated BRCA1 gene, a poor zip code, and a proclivity to sit around eating Pringles while playing Fortnite? That teenager is not going to be able to afford health insurance.

Put another way, adding personalized data to the insurance commons destroys the fabric of that commons. Healthcare has been resistant to this force until recently, but we’re already seeing the same forces at work in other aspects of our previously shared public goods.

A public good, to review, is defined as “a commodity or service that is provided without profit to all members of a society, either by the government or a private individual or organization.” A good example is public transportation. The rise of data-driven services like Uber and Lyft have been a boon for anyone who can afford these services, but the unforeseen externalities are disastrous for the public good. Ridership, and therefore revenue, falls for public transportation systems, which fall into a spiral of neglect and decay. Our public streets become clogged with circling rideshare drivers, roadway maintenance costs skyrocket, and – perhaps most perniciously – we become a society of individuals who forget how to interact with each other in public spaces like buses, subways, and trolley cars.

Once you start to think about public goods in this way, you start to see the data-driven erosion of the public good everywhere. Our public square, where we debate political and social issues, has become 2.2 billion data-driven Truman Shows, to paraphrase social media critic Roger McNamee. Retail outlets, where we once interacted with our fellow citizens, are now inhabited by armies of Taskrabbits and Instacarters. Public education is hollowed out by data-driven personalized learning startups like Alt School, Khan Academy, or, let’s face it, YouTube how to videos.

We’re facing a crisis of the commons – of the public spaces we once held as fundamental to the functioning of our democratic society. And we have data-driven capitalism to blame for it.

Now, before you conclude that Battelle has become a neo-luddite, know that I remain a massive fan of data-driven business. However, if we fail to re-architect the core framework of how data flows through society – if we continue to favor the rights of corporations to determine how value flows to individuals absent the balancing weight of the public commons – we’re heading down a path of social ruin. ProPublica’s warning on health insurance is proof that the problem is not limited to Facebook alone. It is a problem across our entire society. It’s time we woke up to it.

So what do we do about it? That’ll be the focus of a lot of my writing going forward. As Hardin writes presciently in his original article, “It is when the hidden decisions are made explicit that the arguments begin. The problem for the years ahead is to work out an acceptable theory of weighting.” In the case of data-driven decisioning, we can no longer outsource that work to private corporations with lofty sounding mission statements, whether they be in healthcare, insurance, social media, ride sharing, or e-commerce.

Originally published here.

2018 July 27