Category Archives: Leadership Legacy

Thought of the Day – What You Leave Behind

Pericles is perhaps best remembered for a building program centered on the Acropolis which included the Parthenon and for a funeral oration he gave early in the Peloponnesian War, as recorded by Thucydides. In the speech he honored the fallen and held up Athenian democracy as an example to the rest of Greece.

Thought of the Day – Leaving Things Better Than You Found Them

Thought of the Day: On Acting in Anger

Thought of the Day: On Leadership Integrity

Thought of the Day: On Life’s Writing

Leadership & Project Management: Must See

When Financial Performance Matters

https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/thoughts-ken-kaufman/when-financial-performance-matters

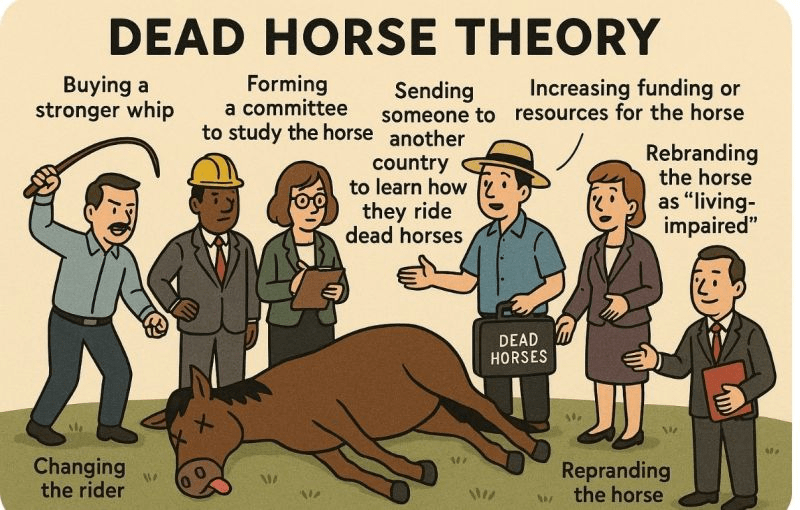

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

In behavioral economics, the sunk cost fallacy describes the tendency to carry on with a project or investment past the point where cold logic would suggest it is not working out. Given human nature, the existence of the sunk cost fallacy is not surprising. The more resources—time, money, emotions—we devote to an effort, the more we want it to succeed, especially when the cause is an important one.

Under normal circumstances, the sunk cost fallacy might qualify as an interesting but not especially important economic theory. But at the moment, given that 2022 will likely be the worst financial year for hospitals since 2008 and given that the hospital revenue/expense relationship seems to be entirely broken, there is little that is theoretical about the sunk cost fallacy. Instead, the sunk cost fallacy becomes one of the most important action ideas in the hospital industry’s absolutely necessary financial recovery.

Historically, cases of the sunk cost fallacy can be relatively easy to spot. However, in real time, cases can be hard to identify and even harder to act on. For hospital organizations that are subsidizing underperforming assets, identifying and acting on these cases is now essential to the financial health of most hospital enterprises.

For example, perhaps the asset that is underperforming is a hospital acquired by a health system. (Although this same concept could apply to a service line or a related service such as a skilled nursing facility, ambulatory surgery center, or imaging center.) The costs associated with integrating an acquired hospital into a health system are typically significant. And chances are, if the hospital was struggling prior to the acquisition, the purchaser made substantial capital investments to improve the performance.

As time goes on, if the financial performance of the entity in question continues to fall short, hospital executives may be reluctant to divest the asset because of their heavy investment in it.

This understandable tendency can lead the acquiring organization to throw good money after bad. After all, even when an asset is underperforming, it can’t be allowed to deteriorate. In the case of hospitals, that’s not just a matter of keeping weeds from sprouting in the parking lot. The health system often winds up supporting an underperforming hospital with both working capital and physical capital, which compounds the losses.

And the costs don’t stop there, because other assets in the system are supporting the underperforming asset. This de facto cross-subsidy has been commonplace in hospital organizations for decades. Such a cross subsidy was probably never sustainable, but it is even less so in the current challenging financial environment.

This is a transformative period in American healthcare, when hospital organizations are faced with the need to fundamentally reinvent themselves both financially and clinically. The opportunity costs of supporting assets that don’t have an appropriate return are uniquely high in such an environment. This is true whether the underperforming asset is a hospital in a smaller system, multiple hospitals in a larger system, or a service line within a hospital.

The money that is being funneled off to support underperforming assets may be better directed, for example, toward realigning the organization’s portfolio away from inpatient care and toward growth strategies. In some cases, the resources may be needed for more immediate purposes, such as improving cash flow to support mission priorities and avoiding downgrades of the organization’s credit rating.

The underlying principle is straightforward:

When a hospital supports too many low-performing assets, the capital allocation process becomes inefficient. Directing working capital and capital capacity toward assets that are dilutive to long-term financial success means that assets that are historically or potentially accretive don’t receive the resources they need to grow and thrive. The underlying principle is a clear lose-lose.

In the highly challenging current environment, it is especially important for boards and management to recognize the sunk cost fallacy and determine the right size of their hospital organizations—both clinically and financially.

Some leadership teams may determine that their organizations are too big, or too big in the wrong places, and need to be smaller in order to maximize clinical and balance-sheet strength. Other leadership teams may determine that their organizations are not large enough to compete effectively in their fast-changing markets or in a fast-changing economy.

Organizational scale is a strategy that must be carefully managed. A properly sized organization maximizes its chances of financial success in this very difficult inflationary period. Such an organization invests consistently in its best performing assets and reduces cross-subsidies to services and products that have outlived their opportunity for clinical or financial success.

Executives may see academic economic theory as arcane and not especially relevant. However, we have clearly entered a financial moment when paying attention to the sunk cost fallacy will be central to maintaining, or recovering, the financial, clinical, and mission strength of America’s hospitals.

5 fatal flaws of healthcare leaders: inspired by HBO’s ‘Succession’

HBO’s critically acclaimed series Succession recently concluded its fourth and final season with a crescendo of family dramatics and falls from grace. If you haven’t seen the finale, bookmark this article for later. It contains spoilers.

Succession, for those unfamiliar, centers on the uber-wealthy Roy family, majority owners of the global media and entertainment subsidiary Waystar Royco. The plot revolves around the bullishly Machiavellian patriarch Logan Roy and his four adult children, each of them seeking (a) control of the family business and (b) their dad’s approval.

During its run, the show’s endless infighting and fascinating archetypes captivated viewers. But the 39-episode series also provided enduring lessons in dysfunctional leadership, which apply directly and saliently to U.S. healthcare.

As with Waystar Royko, the institutions of medicine (hospitals, medical groups, insurers, pharma and med-tech companies) need excellent leadership just to survive. With millions of dollars and hundreds or thousands of jobs resting on the decisions of top administrators, any major flaw can prove fatal—erasing decades of organizational success.

In any industry, poor leadership can undermine performance and threaten livelihoods. In healthcare, poor leadership puts lives at risk. Here are five dangerous types of leadership personalities, each inspired by a character from Succession:

1. Connor Roy: the delusional leader

In the show’s second season, Connor, the eldest and oft-forgotten son of Logan Roy, launches his U.S. presidential campaign on a “no-tax” platform. When the eve of election arrives, he’s polling at less than 1%, yet he refuses to step aside, still convinced he is capable of doing the job.

Like Connor, healthcare’s delusional leaders overestimate their abilities. Their ideas are unrealistic and their vision for the future: pure fiction. But no matter how outlandish their outlook, delusional leaders will always find apostles among the disenfranchised who, themselves, feel undervalued and overlooked.

When confronted with the harshness of reality, deluded leaders and their followers double down, insisting that everyone else is myopic. “Just follow and you’ll see,” they demand.

Unless senior executives or board members step in to relieve this leader of power, the organization will be as doomed as Connor Roy’s bid for presidency.

2. Kendall Roy: the narcissistic leader

On the surface, Kendall is by far the most capable and experienced candidate to succeed his father. He’s a smart and articulate heir apparent who appears up to the task of CEO.

But underneath the gold plating, his every action is reflexively self-centered. As such, when the time comes to sacrifice something of himself for the good of the company, he freezes and falters, his decisions corrupted by the compulsion to put himself first.

Like Kendall, healthcare’s narcissistic leaders bask in praise and blind loyalty. They reject and punish those who provide honest feedback and fair criticism. Their obsession with status and self-importance blinds them to long-term threats and opportunities, alike.

Unlike delusional leaders, who fail because their vision cuts against the grain of reality, the narcissistic leader’s passion for winning may advance an organization—in the short run. Long-term, however, their flaws will be exposed and weaknesses manipulated by seasoned competitors.

Across four seasons, Kendall can’t fathom that anyone else might be a better choice to run the company. As a result, he underestimates a rival CEO who’s seeking to acquire Waystar, and he overestimates the loyalty of his siblings. In the end, he’s left hopeless and broken.

3. Roman Roy: the immature leader

Roman, the youngest Roy, is brash and witty, but also unpredictable and unrestrained. His penchant for foul language and cutting insults make for good television, but they’re the telltale signs of insecurity and immaturity.

Like all immature leaders, Roman is addicted to novelty and excitement, often acting without regard for the consequences. He’s fast-talking and loud, which makes him likable enough for many to overlook his incompetence. But he’s incapable of filling his father’s shoes.

Immature leaders get promoted before they’re primed and polished. They often lack boundaries and excel at the sport of making others uncomfortable. At times, they seem more interested in causing a scene than creating results. They chase big ideas—if only for the adrenaline rush—but can’t accurately calculate whether the risk of failure is 20% or 80%. This makes them very dangerous as leaders.

4. Shiv Roy: the political leader

In a world of deluded and despotic men, Shiv comes across as the voice of reason. Smart and strategic, relaxed and composed, Shiv carefully cultivates new allies but never establishes an identity of her own. This makes her an excellent political consultant (the job she has) but a poor candidate for CEO (the job she wants).

Political leaders are better at advancing within an organization than advancing the organization itself. Like chameleons, these leaders change with the scenery, shifting alliances and values as organizational power waxes and wanes. While they’re busy focusing on rumors and relationships, they fail to muster real-life business acumen and experience.

Colleagues rarely respect those who play organizational politics. Once political leaders have accrued enough power and advanced their careers to the max, their shallow alliance and inability to drive performance leaves them stranded at the top—with nowhere to go but down.

5. Tom Wambsgans: the compromised leader

Not technically a Roy, Tom is Shiv’s husband and an eager aspirant for CEO.

Once appointed head of Waystar’s struggling cruises division, Tom conceals damaging information to protect his father-in-law. He is a willing henchman, ready to sacrifice his ethics for a shot at the corner office. To advance his interest, Tom repeatedly compromises his integrity, first with Logan, then Kendall, and eventually Lukas Matsson, the incoming global CEO who completes the hostile takeover of Waystar.

In what proves to be Tom’s final interview for U.S. CEO, Matsson asks him whether he will be willing to play the role of “pain sponge,” absorbing any negative fallout the company may experience. After he responds positively, Matsson tests him further by mentioning that he’d like to have sex with Shiv. While viewers squirm in their seats, Tom doesn’t object. For him, every compromise is simply a means to an end.

Compromised leaders are skilled at making promises. They seek support by vowing to fulfill wants and palliate pains. Depending on who these leaders aim to please, they’re willing to slash budgets or raise salaries, regardless of the financial impact. Ultimately, they’ll do anything to keep people happy, even if they have to sink the business in the process.

The three attributes of excellent healthcare leaders

In the final season of Succession, Logan tells his offspring, “I love you, but you are not serious people.” He is both accurate and accountable. Logan was not a serious father and, as a result, his kids were poorly equipped for life and leadership.

The healthcare industry is replete with stories of once-successful institutions falling on hard times under poor leadership. Although there’s no one way to run an organization, all great healthcare leaders share three characteristics:

1. A clear mission and purpose

Leaders have three jobs. They must create a vision, align people around it and motivate them to succeed. To accomplish these tasks, executives may use carrots and sticks, incentives and disincentives, or positive and negative reinforcement. But these tactics will fail unless they reflect a clear mission and purpose.

Years ago, former CMS administrator Don Berwick started a program with an audacious goal of maximizing patient safety and preventing unnecessary deaths. He called it the 100,000 Lives Campaign. And when he spoke of the program, he leaned hard on its righteous mission. Instead of presenting metrics and statistics, he talked about the weddings and graduation ceremonies that parents and grandparents would attend, thanks to the program and the people behind it. Even hard-weathered clinicians in the audience had tears in their eyes.

Financial incentives drive change in healthcare, but rarely achieve the outcomes intended. Everyone engaged in the 100,000 Lives Campaign knew exactly what they needed to accomplish and were motivated to do so.

2. Experience and expertise

Bold ideas and glittering promises always capture attention. Words are powerful and relationships can take aspiring leaders far. But when it comes time to turn big plans into action, there is no substitute for a leader who has been there and done it well.

Exceptional performance, not promises, separate great leaders from the rest—and success from failure. In every industry, past performance is the best predictor of future success. Of course, poor leaders can get lucky and even great ones in bad circumstances may fail. But the odds always favor those who have achieved recurring success throughout their careers.

3. Personal integrity

Emerging leaders can work on their weaknesses. Coaching, training and even therapy can help them quell maladaptive behaviors.

But everything changes when an emerging leader becomes the head of an organization and faces a crisis. As risks and pressures intensify, people tend to fall back on approaches and habits they learned in the past, particularly problematic ones. Whenever tested, the Roy children did exactly that.

After Logan’s death early in the final season, the fatal flaws of each Roy child came into clear view. As a result, the Waystar board made the safest choice for successor: none of the above.

Like a true Shakespearean tragedy, the flaws of the characters in Succession exceeded their abilities.

In healthcare, that’s a guaranteed prescription for failure.

Is the Traditional Hospital Strategy Aging Out?

https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/thoughts-ken-kaufman/traditional-hospital-strategy-aging-out

On October 1, 1908, Ford produced the first Model T automobile. More than 60 years later, this affordable, mass produced, gasoline-powered car was still the top-selling automobile of all time. The Model T was geared to the broadest possible market, produced with the most efficient methods, and used the most modern technology—core elements of Ford’s business strategy and corporate DNA.

On April 25, 2018, almost 100 years later, Ford announced that it would stop making all U.S. internal-combustion sedans except the Mustang.

The world had changed. The Taurus, Fusion, and Fiesta were hardly exciting the imaginations of car-buyers. Ford no longer produced its U.S. cars efficiently enough to return a suitable profit. And the internal combustion technology was far from modern, with electronic vehicles widely seen as the future of automobiles.

Ford’s core strategy, and many of its accompanying products, had aged out. But not all was doom and gloom; Ford was doing big and profitable business in its line of pickups, SUVs, and -utility vehicles, led by the popular F-150.

It’s hard to imagine the level of strategic soul-searching and cultural angst that went into making the decision to stop producing the cars that had been the basis of Ford’s history. Yet, change was necessary for survival. At the time, Ford’s then-CEO Jim Hackett said, “We’re going to feed the healthy parts of our business and deal decisively with the areas that destroy value.”

So Ford took several bold steps designed to update—and in many ways upend—its strategy. The company got rid of large chunks of the portfolio that would not be relevant going forward, particularly internal combustion sedans. Ford also reorganized the company into separate divisions for electric and internal combustion vehicles. And Ford pivoted to the future by electrifying its fleet.

Ford did not fully abandon its existing strategies. Rather, it took what was relevant and successful, and added that to the future-focused pivot, placing the F-150 as the lead vehicle in its new electric fleet.

This need for strategic change happens to all large organizations. All organizations, including America’s hospitals and health systems, need to confront the fact that no strategic plan lasts forever.

Over the past 25-30 years, America’s hospitals and health systems based their strategies on the provision of a high-quality clinical care, largely in inpatient settings. Over time, physicians and clinics were brought into the fold to strengthen referral channels, but the strategic focus remained on driving volume to higher-acuity services.

More recently, the longstanding traditional patient-physician-referral relationship began to change. A smarter, internet-savvy, and self-interested patient population was looking for different aspects of service in different situations. In some cases, patients’ priority was convenience. In other cases, their priority was affordability. In other cases, patients began going to great lengths to find the best doctors for high-end care regardless of geographic location. In other cases, patients wanted care as close as their phone.

Around the country, hospitals and health systems have seen these environmental changes and adjusted their strategies, but for the most part only incrementally. The strategic focus remains centered on clinical quality delivered on campus, while convenience, access, value, affordability, efficiency, and many virtual innovations remain on the strategic periphery.

Health system leaders need to ask themselves whether their long-time, traditional strategy is beginning to age out. And if so, what is the “Ford strategy” for America’s health systems?

The questions asked and answered by Ford in the past five years are highly relevant to health system strategic planning at a time of changing demand, economic and clinical uncertainty, and rapid innovation. For example, as you view your organization in its entirety, what must be preserved from the existing structure and operations, and what operations, costs, and strategies must leave? And which competencies and capabilities must be woven into a going-forward structure?

America’s hospitals and health systems have an extremely long history—in some cases, longer than Ford’s. With that history comes a natural tendency to stick with deeply entrenched strategies. Now is the time for health systems to ask themselves, what is our Ford F150? And how do we “electrify” our strategic plan going forward?