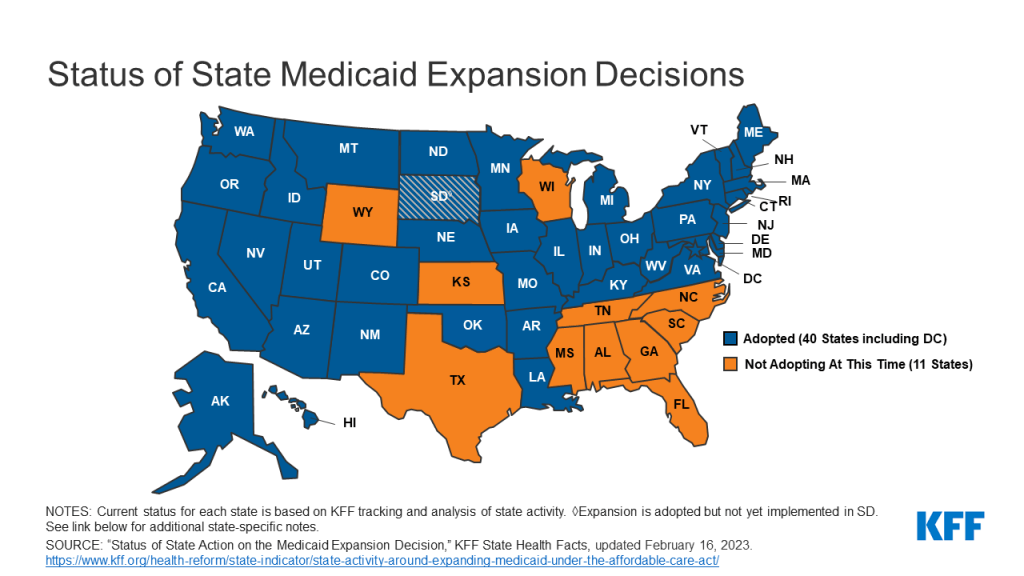

North Carolina is poised to become the 40th state to expand Medicaid.

Yesterday afternoon, Gov. Roy Cooper (D) signed legislation crafted by the state’s two Republican leaders, an unlikely deal that puts an end to an over-a-decade-long political battle.

But North Carolina may be the last of the Medicaid expansion holdout states to reverse course for a while. Supporters of extending the safety net coverage to hundreds of thousands more low-income adults have repeatedly run into Republican resistance in the 10 states that have long refused the Obamacare program — and another victory isn’t imminent.

“Now we’re down to some of the hardest states to get expansion through,” said Frederick Isasi, the executive director of Families USA, a left-leaning consumer health lobby, though he expressed confidence the remaining states would eventually budge.

Over the years, some steadfast GOP opposition to Medicaid expansion has softened, such as in North Carolina. The 2010 Affordable Care Act required states to extend the safety net program up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, but the Supreme Court made doing so voluntary.

The ballot measures

Since 2017, advocates have put expanding Medicaid directly to voters in seven conservative-leaning states. They argued it would bring federal taxpayer dollars back to their state and help struggling rural hospitals — and the ballot measures passed in every instance.

But that strategy may be almost exhausted. Three of the holdout states have had citizen-led ballot measure processes — Florida, Wyoming and Mississippi — but at the moment, that path only appears viable in one state.

That’s Florida, where Medicaid advocates have their eye on fall 2026. Florida Decides Healthcare, a political committee supporting expansion, estimates it’ll cost roughly $10 million just to gather enough signatures to get the measure on the ballot, according to Jake Flaherty, the group’s campaign manager.

- Even if that happens in a few years, there’s another hurdle. An amendment to the constitution must garner the support of 60 percent of voters. Only once — in Idaho — has that happened for Medicaid expansion.

The prospects are dim in the near future for the other two states. Wyoming advocates don’t believe they can use the ballot measure process to expand Medicaid, citing a mandate that an initiative not “make appropriations.” The next best chance is likely 2025, when the state legislature convenes again for a general session, according to Nate Martin, the executive director of Better Wyoming.

And in Mississippi, advocates filed paperwork to launch an expansion campaign in 2021. But it had to disband a month later when the state Supreme Court nullified the ballot measure process until state lawmakers fixed it, which the legislature failed to do this year, the Clarion Ledger reported.

Other states

North Carolina is the first state to expand Medicaid through the legislature since Virginia in 2018. And it’s still not finalized: The expansion is tied to the state passing a new budget, which is expected to occur over the summer.

Other states that haven’t expanded include Alabama, Georgia, Kansas, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Wisconsin. Republicans opposing expansion have often cited fiscal concerns with the policy, which supporters push back against and have pointed to extra two-year incentives signed into law in 2021.

Several advocates said they’re watching Alabama closely, and that Gov. Kay Ivey (R) has the power to expand Medicaid without the GOP-led legislature’s sign-off. Last week, a House committee held an educational meeting on addressing the state’s coverage gap, the Alabama Reflector reported. In a statement to The Health 202, spokesperson Gina Maiola wrote that “the governor’s concern remains how the state would pay for it long-term.”

And in Kansas, Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly has been pushing the issue for years. But it’s an uphill battle to get it passed this year amid some Republican opposition, Will Lawrence, her chief of staff, acknowledged in an interview. Lawrence said he believes if a deal can be reached with the House speaker at some point, then the Senate may come along.

- “We’ll continue to push those conversations,” Lawrence said. He added: “If it doesn’t happen this session, then we’ll be working over the summer and fall, like we did a few years ago, and we’ll come back with a strong push in January of next year.”