For a small group of vascular surgery centers in metropolitan Washington, D.C., it was local churches that turned out to be surprisingly lucrative.

It was at health screening fairs hosted by these houses of worship where Marty Makary, M.D., found surgeons drumming up business for pricey—and often unnecessary—leg stents. It’s among the collection of systemic and human examples Makary examines in his new book “The Price We Pay: What Broke American Health Care—and How to Fix It” as driving forces behind rising U.S. health costs.

Makary, a surgeon at Johns Hopkins and New York Times best-selling author, hits every segment of the market, from a health system in New Mexico that has sued 1 in 5 residents in town to a health insurance conference where brokers described over drinks why they usually aren’t helping employers get the best deal.

“Healthcare has adopted a business model that uses middlemen, price gouging and sometimes delivers care that can be inappropriate, and this bloated economy has a tremendous amount of waste,” Makary said. “So our research really asks the question: ‘What is the experience of the everyday American interfacing with our healthcare system?’”

I caught up with Makary recently to discuss some of the problems he highlights in his new book, which is being released Sept. 10, and some of his ideas on how we solve them.

FierceHealthcare: Why did you write this book?

Marty Makary: Hospitals are amazing places and there is a tremendous amount of public trust in hospitals. But I’ve been seriously concerned about the erosion of public trust by the price gouging and predatory billing practices that patients are describing all over America. Our research team found bills are marked up as much as 23 times higher than what hospitals will accept from Medicare. We kept hearing over and over again that, ‘No one is expected to pay these bills. Hospital CEOs assured me when I showed them inflated bills that nobody is expected to pay the sticker price.’ But that didn’t seem to match the stories we were hearing on the ground.

FH: One of the hospitals you highlight in this book in Carlsbad, New Mexico, had a practice of hiking prices and suing patients who were unable to pay. What did you find there?

MM: We decided to shift our research into the question: “Are Americans asked to pay the sticker price and if so, what happens when they can’t afford it?”

A woman sent me a message where not only was the bill inflated, but the care was—in her opinion, unnecessary—and the hospital had sued her. When I reached out, she said, “They’ve sued all my friends as well and garnished our paychecks.” I couldn’t believe this, and so I flew out to Carlsbad. The driver of the Chamber of Commerce taxi service that picked us up from the airport, the receptionist at the hotel, the waitress at the breakfast place, the clerk’s office staff, families in the courthouse: You couldn’t believe it. Everywhere you turned, people had been terrorized financially by this local community hospital. I thought: “Where is the spirit of medicine? Do these executives even know the consequences on the ground of these billing practices?”

FH: In the book, you mention many hospital executives don’t even know they’re suing patients.

MM: Oftentimes, there’s detachment. And when we’re detached from the consequences or problems, that’s when horrible things happen in societies historically. I found sometimes hospital executives, board members and certainly our research supports doctors not knowing about this practice. And when they find out, the clinicians are outraged. By and large, board members want it to stop … I think if you look at any major issue in the United States, whether it be race, poverty or healthcare, if we are not proximate to the problem, we tend to rationalize financial systems that enable the problem. In healthcare, what I’ve noticed is, when I would share these stories at conferences, other healthcare experts argued it was not a problem that was diabolical, they just weren’t proximate to the issue.

FH: You also document that many hospitals are doing the right thing.

MM: Most hospitals try to do the right thing. But I think it tells us a lot about the practice of suing patients and that it’s unnecessary. When all the revenue generated from suing patients amounts to less than the amount of the CEO pay increase in one year, which is something we’ve seen, the argument that it’s essential to sue patients in order for the hospital to be sustainable melts away.

FH: But obviously, the problem is not just about hospitals, right?

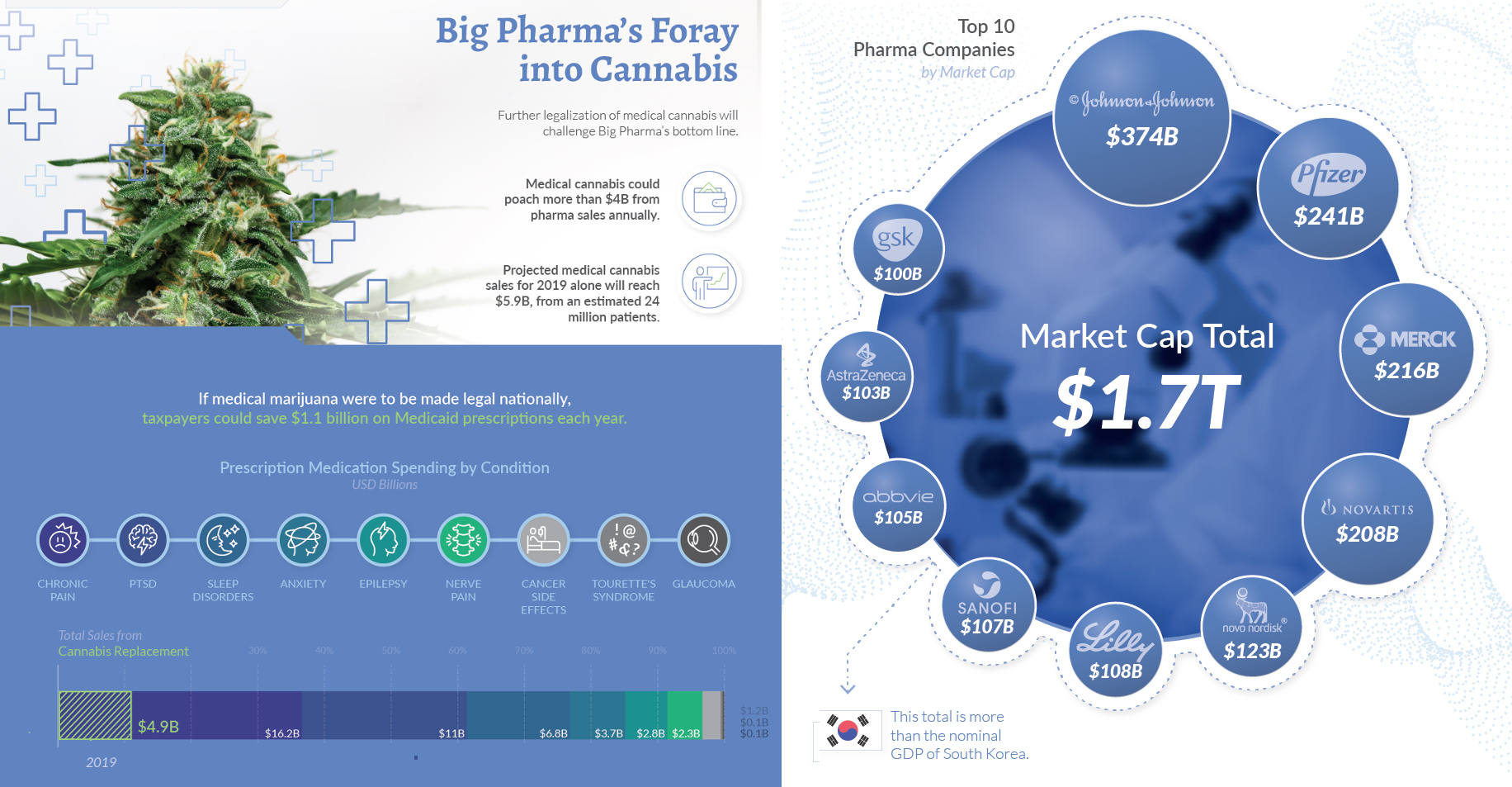

MM: A lot of people are getting rich in healthcare. We’ve created tens of thousands of millionaires that are not patient-facing. If you look at the earnings on Wall Street of some of these healthcare companies, for example, UnitedHealth Group reported a 25% increase in earnings in a recent earnings report. How do earnings go up 25% in an actuarial insurance business? They said on their call it was in part due to their pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), a well-known middleman that profits from spread pricing and money games. Hospitals are on target this year for their highest margin in history—5.1% based on early 2019 data. At the same time rural hospitals are closing, large hospitals are making barrels of money. Although they are claiming razor-thin margins, the cost shift accounting is so sophisticated, that they can use their profit to buy new buildings, pay down debt, buy more real estate, increase executive pay. What we have right now is an arms race of profiteering in healthcare where all the stakeholders are making a lot of money except for one, and that’s the patient.

FH: In the book, you talk about efforts to address practice outliers like those vascular surgeons through the use of big data, which led to the creation of the “Improving Wisely” initiative. What did you do?

MM: Most doctors do the right thing or always try to. But the fraction that are responding to the consumerist culture or the perverse incentives or are just not practicing state of the art care can cost the system a lot more money than those who aren’t … Instead of hammering doctors that do the right thing with reporting burdens and other hassles, we can shunt those resources to address outliers identified in the data using metrics endorsed by the experts in each specialty, and gold card the good doctors so they don’t have to deal with reporting hassles and the expense of the reporting hassles.

In studying the issue of inappropriate care and delivering measures of the appropriateness of care, we’ve been meeting with individual specialists around the country and many of these doctors are telling us about the practice pattern that a fraction of specialists in their field are doing that represents overuse. Our work called “Improving Wisely” partners with associations to send outlier physicians their data around a specialty-endorsed measure of overuse. What we’ve seen is, among doctors, among outlier physicians who see their data with a confidential dear doctor letter, that 83% reduce their pattern of overuse. The initial project two years ago that cost $150,000 has resulted in $27 million worth of savings. This is an example of a high consensus approach that results in real savings that you just don’t see in other areas. By and large, politicians are talking about different ways to fund the broken healthcare system and not ways to fix it. We need to talk about how to fix it.

FH: In the book, you really seem to try to take on everyone: doctors, hospitals, air ambulances, workplace wellness companies, PBMs.

MM: Almost all the voices in healthcare are beholden to some special interest or stakeholder. We desperately need a global critique of how this system has gone awry and there’s a lot of finger-pointing going on right now, especially at the insurance companies and pharma. But the reality is, we all have a piece of this pie. I don’t think there’s really any one villain in the healthcare system. I don’t even think there’s much deliberate malfeasance that goes on. I think we have a system that’s largely run by people doing what they are told to do and they are doing it in a place where they may not be proximate to the hardship the system creates.

FH: So the big question: How do we fix the problems?

MM: For every problem I described, I tried to describe one of the most exciting disrupters in this space. With the pricing failure problem, I highlight the Free Market Medical Association and the individuals who are saying they are going to make all prices transparent and fair regardless of who’s paying whether it’s a patient or an insurance company. There’s one fair price. Keith Smith of the Surgery Center of Oklahoma is offering one fair true price. Not a sticker price but a true price, regardless of who’s paying. You look at MDsave and Clear Health Costs. They are offering ways for people to shop. If the government does nothing on healthcare, I’m still optimistic we are moving in the right direction because businesses in American are realizing that they’re getting ripped off on their healthcare and pharmacy plans. They’re increasingly doing direct contracting and looking closely at their health insurance benefits and pharmacy design and realizing there is a lot of money wasted.

One of the root issues in healthcare is the way we physicians are educated. It uses a model that’s highly flawed, relying highly on rote memorization of things that are easily available on the Internet today and omits training in effective communication, public policy and healthcare literacy. It turns out that many doctors feel paralyzed in fixing this broken system even as they’re suspicious of the waste in it. One of the goals of writing the book was creating healthcare literacy because we in the field are taught medical literacy but we’re never taught healthcare literacy. One of the exciting disrupters I had the privilege of spending time was the Sidney Kimmel Medical College (in Philadelphia). They have an academic standard in the admissions process. Once people meet that academic standard, everybody is considered based on their empathy, self-awareness and communication skills. It’s revolutionary as simple as it sounds. But they’re focusing on what matters.