More than 99.99% of people fully vaccinated against Covid-19 have not had a breakthrough case resulting in hospitalization or death, according to the latest data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.The data highlights what leading health experts across the country have highlighted for months: Covid-19 vaccines are very effective at preventing serious illness and death from Covid-19 and are the country’s best shot at slowing the pandemic down and avoiding further suffering.The CDC reported 6,587 Covid-19 breakthrough cases as of July 26, including 6,239 hospitalizations and 1,263 deaths. At that time, more than 163 million people in the United States were fully vaccinated against Covid-19.

Divide those severe breakthrough cases by the total fully vaccinated population for the result: less than 0.004% of fully vaccinated people had a breakthrough case that led to hospitalization and less than 0.001% of fully vaccinated people died from a breakthrough Covid-19 case.

Most of the breakthrough cases — about 74% — occurred among adults 65 or older.

Since May, the CDC has focused on investigating only hospitalized or fatal Covid-19 cases among people who have been fully vaccinated. The agency says the data relies on “passive and voluntary reporting” and is a “snapshot” to “help identify patterns and look for signals among vaccine breakthrough cases.”

“To date, no unexpected patterns have been identified in the case demographics or vaccine characteristics among people with reported vaccine breakthrough infections,” according to the CDC.

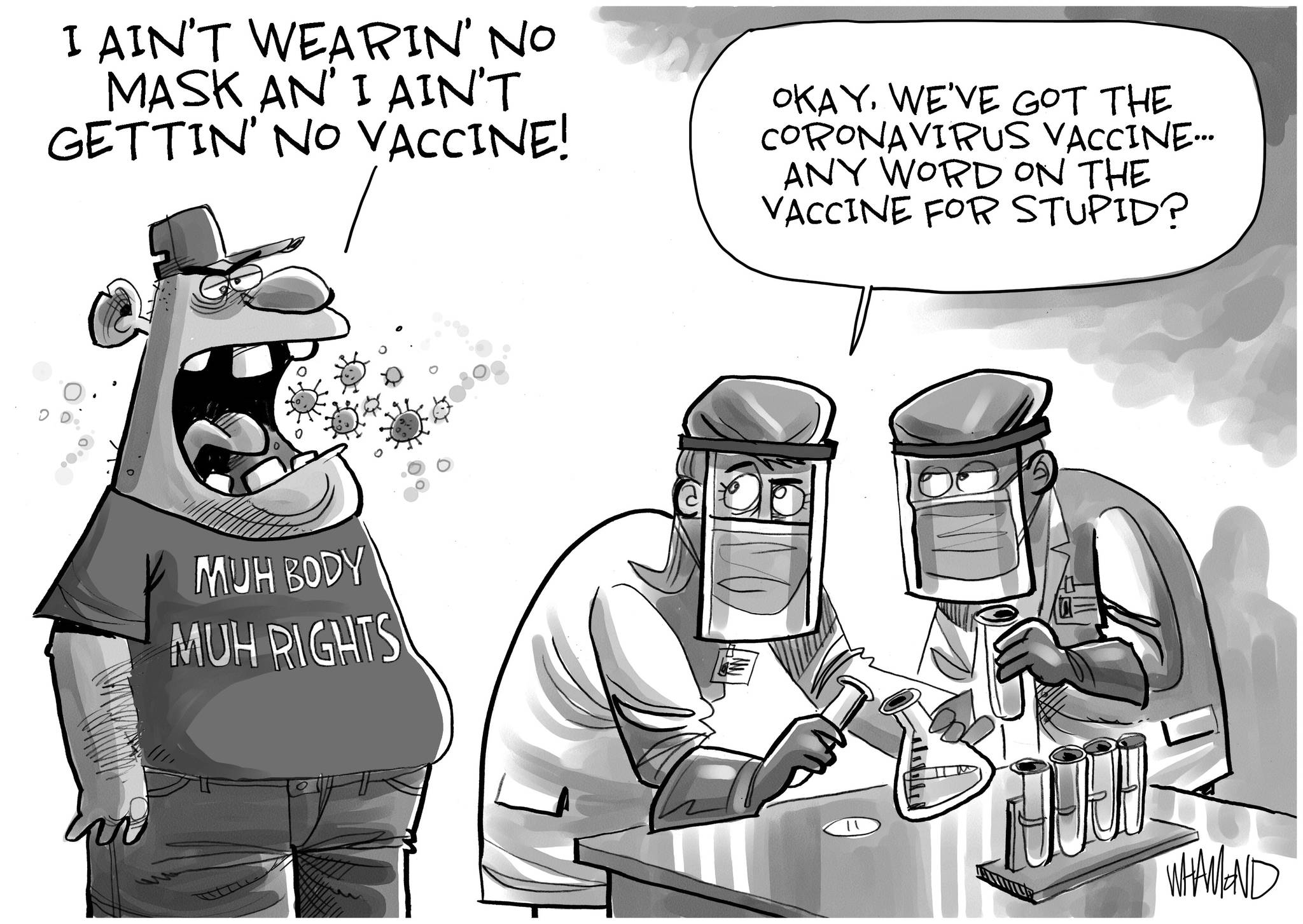

The agency shared a study this week that showed the Delta variant produced similar amounts of virus in vaccinated and unvaccinated people if they get infected. Experts continue to say that vaccination makes it less likely you’ll catch Covid-19 in the first place. But for those who do, the findings suggest they could have a similar tendency to spread it as unvaccinated people. That study also convinced CDC leaders to update the agency’s mask guidance on Tuesday, recommending that fully vaccinated people also wear masks indoors when in areas with “substantial” and “high” Covid-19 transmission to prevent further spread of the Delta variant. Guidance for unvaccinated people remains to continue masking until they are fully vaccinated. Beyond severe cases, an analysis of official state data from the Kaiser Family Foundation showed that breakthrough cases of any kind are also extremely rare.vAbout half of states report data on Covid-19 breakthrough cases, and in each of those states, less than 1% of fully vaccinated people had a breakthrough infection, ranging from 0.01% in Connecticut to 0.9% in Oklahoma.

The KFF analysis also found that more than 90% of cases — and more than 95% of hospitalizations and deaths — have been among unvaccinated people. In most states, more than 98% of cases were among the unvaccinated.

Pace of vaccinations is going up

But experts say those vaccinated, while they may be able to transmit the virus, remain very well protected against getting seriously ill. Amid the latest surge of Covid-19 cases nationwide fueled by the Delta variant, local leaders across the US are reporting that the majority of new infections and hospitalizations are among unvaccinated people. The Delta variant is now so contagious, one former health official recently warned that people who are not protected — either through vaccination or previous infection — will likely get it. Amid concerns over the rising cases and the dangerous strain, the country has seen a steady rise in the pace of vaccinations in the past three weeks — and an even sharper increase in states that had been lagging the most, according to a CNN analysis of CDC data.

The seven-day average of new doses administered in the US is now 652,084, up 26% from three weeks ago. The difference is even more striking in several southern states: Alabama’s seven-day average of new doses administered is more than double what it was three weeks ago. The state has the lowest rate of its total population fully vaccinated in the US, at roughly 34%. Arkansas, with just 36% of its population fully vaccinated, has also seen its average daily rate of doses administered double in the last three weeks. Louisiana, which had by far the most new Covid-19 cases per capita last week and has only fully vaccinated 37% of its population, saw daily vaccination rates rise 111% compared to three weeks ago.

Meanwhile, Missouri, which has been among the hardest-hit states in the latest Covid-19 surge, now has a daily average of new vaccinations 87% higher than three weeks ago.

Roughly 57.5% of the US population has received at least one Covid-19 vaccine dose and about 49.5% is fully vaccinated, CDC data shows.