They were late filing a claim. Now I’m in collections.

Hey there —

I get a lot of questions from An Arm and a Leg listeners. Sometimes I write back with advice. So: Why not share? Welcome to an experiment: Our occasional advice column!

Maybe let’s call it: Can they freaking DO that?!?

Disclaimer: I don’t know everything, I’m not a lawyer, and I haven’t done new reporting for this. It’s the kind of advice I’d give a friend.

Or, in this case, a listener named Chris.

Q: Can they charge me $47,000 for their mistake?

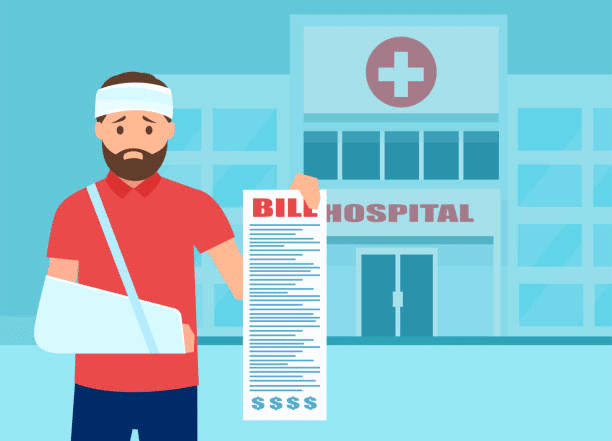

I had an emergency appendectomy. The hospital rang me up for about $47,000 — but, insurance denied the claim because they say the hospital didn’t submit it to them until eight months after the fact — beyond their 60-day “timely filing” limit in the contract [between the hospital and the insurance company].

After that, the hospital started billing me.

I have spent hours and hours on the phone over the last two months with various people in their billing department. I followed their recommendation to send a letter, and an email, requesting that they write off these charges since it was their billing error — and nothing has been fixed.

Now they’ve sent me to collections.

What do I do now? Do I sue? How can I sue? Help!

Chris

A: Don’t run for a lawyer (yet)

Chris, thanks so much for writing in — and YIKES.

I think you’re zeroing in on the right question, which is: How can you demand redress?

Put another way: Where’s your leverage? How can you get them to see they’re better off dealing with you in good faith, versus… getting themselves in actual trouble?

I don’t think you need to run out and hire a lawyer. But there’s a bunch of homework to do.

Start with your insurance

Because it’s their job to protect you from getting unfairly harassed like this.

Sounds like the hospital promised the insurance company — in a contract — to submit bills within 60 days.

That contract probably does not say, “and if we’re late on that, we’ll just go after Chris.”

No. I’m thinking it says, “If we don’t get you that bill on time, that’s just too bad for us.”

So: the insurance company has a right — and an obligation to you — to tell the hospital where to stick that bill.

So ask your insurance company: What’s *supposed* to happen if a hospital doesn’t submit a bill on time? What’s their process for getting things fixed? Can they tell the hospital to just knock it off, already?

And while you’ve got them, you may as well ask: If the hospital had submitted the bill on time, what would you have been on the hook for?

…because when this gets fixed, you’ll probably owe that amount.

If your insurance won’t cough up the info and won’t go to bat for you, get help. If you get your insurance through work, call HR. Otherwise, ring up your state insurance regulator.

Dispute the bill in collections

Meanwhile, you’ve got the hospital siccing a collection agent on you. That’s not right.

Notify the collection agency that you’re disputing this debt, as described in this recent First Aid Kit — which includes a dispute-letter template. (While you’re at it, send a copy to the hospital billing office.)

Document your efforts to get the hospital to see the light on this. If you’ve written to them, attach copies of previous correspondence. If it’s been all phone calls, document them: You called them on this day, at that time, etc.

If you haven’t been logging calls — keeping a set of notes with times, dates, who you spoke to, and where things stood at the end of the call — start now.

Let the hospital know: They could get in trouble

Your state’s consumer-protection office might take a dim view of what the hospital is doing here.

I mean, I’m not a lawyer, but I’m pretty sure there are laws against chasing you for money you don’t actually owe.

Look up that consumer-protection office here. If you can talk with someone there, great. If your state’s consumer-protection laws are easy to find online (and understand), also great.

(If not, consider calling your local public library. Seriously, librarians are amazing at helping dig up useful information.)

Once you’ve got some sense of your legal rights — from the hospital’s contract with the insurance company, from your state’s consumer-protection laws…

Start writing letters. To the hospital, to the collection agency — saying: Let’s get this settled before I have to complain to regulators about this. (When you write to the hospital, maybe cc the General Counsel’s office.)

Let them know how you expect things to go, and indicate — subtly but clearly —that you know what kind of trouble they could be in and why.

And make it all as confident and calm as possible. I’m thinking of something the legal expert Jacqueline Fox told me once:

The person who gets the letter has to make the decision: “Do I ignore this, or do I bring it to my manager?”

And if I was that person and [the letter-writer] was very calm — just saying, “this is happening, and it’s starting to look like this [legal issue] and I want this to be handled according to your processes,” that’s the part I’d find alarming.

If I was that person, I would either make sure it’s handled according to my processes, or give my manager a heads up: that there’s a grownup who seems somewhat irritated.

Somehow, we never actually used that tape, even though I think about it all the time — until now. Thanks for the chance to bring it back.