Cartoon – New Product Enhancement

Late last year, the Christensen Institute’s Rebecca Fogg wrote about disruption accelerating in healthcare, priming of the pump for new capitated health plans and new delivery models. It is certain that leading consultancies have expressed a surging desire to disrupt in their business intelligence work and their analysis holds some insight for business leaders. But the truth about what our healthcare system will look like over the next 20 years is far from determined — and “disruption” will certainly not be the optimal path.

Disruption is, well, disruptive. It leaves in its wake complicating debris that trend towards more disorder. Consider that disruption’s synonyms include breakdown, collapse, disarrangement, disturbance, havoc, upset,… Is this what we actually want or need? Healthcare doesn’t shatter and reanimate, it evolves. Over 200 years ago, for example, the invention of the stethoscope ushered in a series of generational discoveries that transformed public health, general health, and overall life expectancy through the enhancement of insight into pathophysiology underlying human symptoms. The new technology was groundbreaking, but the transformation happened over time and with continuous building upon prior advances. This evolutionary system works remarkably well. To disrupt it, to disarrange it, does not make sense.

At the center of Fogg’s argument is interest in different models that seem to be on the increase. The data does not fully support this view or serve as evidence of a pending wave of disruption. What we see instead are repeated ripples.

Take the “wave” of HMOs initiated in the 1970s. The ramp was supposed to be significant — combining financing and care delivery would be genuinely transformative. And yet the model’s penetration over 20 years only reached about 15 percent nationwide, and even now (data as of 2016) has only increased to 31.6 percent.

Further, in 2014 and again in 2018, Rand Corporation explored health payment constructs. Its most recent report on this work is a great representation of both our progress and stagnation: Findings suggest that in the window between initial engagement around alternative payment models (such as value-based care in 2014) and follow up (in 2018) little in the way of significant change has occurred. While we have seen plenty of perceived “disruptive models” emerge, we’ve also witnessed models championed as “disruptive” fall away.

The rise, plateau, and sometimes decline of various broad modernization initiatives is common and should be expected. The whole effort is hard. We do not have any magical ability to foretell the future. And we do a poor job of grasping the evolutionary nature of healthcare and the timelines of its change. Sure, we see pockets of capitated plan models that work, locations where the ACO makes sense, incidences where bundles show promise. But we are not primed for disruption that will change everything, or even most things, tomorrow. Rather, we are primed for a series of experiments, discoveries, and adaptive evolution. This is OK.

Three points stand out significantly in charting the realistic course of healthcare change moving forward:.

Amid the flurry of articles and analysis expounding the grandiosity of ever-imminent healthcare disruption (just around the corner), a nod to Darwin and the observable nature of our actual healthcare system and a scientifically based understanding of evolution seems appropriate.

Frustrations faced by Americans in paying for healthcare are understandable given that the U.S. ranks first among the 36 OECD developed nations in healthcare cost per person.

But their belief in the supremacy of the U.S. healthcare system is misplaced at best.

The U.S. ranks 31st among the OECD group in terms of infant mortality, a key indicator of overall quality, and a depressing 28th in overall life expectancy.

While healthcare is more regulated in nearly every other developed country, mammoth bills pack a bigger punch because they can come out of nowhere in the U.S. Some 47% of Americans reported never knowing what a visit to the emergency room will cost before receiving care. Just 19% of respondents said they “always” knew their out-of-pocket costs before visiting the ER.

Outpatient surgery, visits to a physical therapist or chiropractor, and check-ups and physicals didn’t fare much better, with only 17%, 23% and 39% of respondents respectively saying they always knew their out-of-pocket costs at those sites of care.

Obfuscation of prices may lead to “risky and unhealthy behavior,” according to the West Health report. It found 41% of Americans surveyed reported forgoing a visit to the ER over the past year due to cost concerns.

And this fear over costs is affecting people at every rung of the socioeconomic ladder. West Health and Gallup found the concern wasn’t just unique to people struggling financially — it was consistent up to the top 10% of earners.

“Angst is a very appropriate word to use when you see the data,” Mike Ellrich, healthcare portfolio leader at Gallup said at the West Health Healthcare Costs Innovation Summit on Tuesday.

Political debate over fixing this problem has centered of late on drug prices, surprise medical bills, pre-existing conditions and lowering insurance premiums, which are rising faster than income. And CMS has prodded providers and payers to make out-of-pocket costs more transparent for patients.

But Americans largely don’t think politicians will be able to fix the problem, with more than two-thirds of Republicans and Democrats alike not at all confident that elected officials will be able to achieve bipartisan legislation to lower costs.

However, perceptions of quality diverged among party lines. West Health and Gallup found 67% of Republicans view the U.S. healthcare system as delivering the best or among the best care in the world. Just 38% of Democrats agreed.

“I’m all for patriotism, but this is a disconnect from reality,” Ellrich said. “This issue is not red or blue.”

https://www.politico.com/story/2019/04/03/obamacare-health-care-crisis-1314382

The ceaseless battle over the 2010 law has made it difficult to address the high cost of American health care.

The Obamacare wars have ignored what really drives American anxiety about health care: Medical costs are decimating family budgets and turning the U.S. health system into a runaway $3.7 trillion behemoth.

Poll after poll shows that cost is the number one issue in health care for American voters, but to a large extent, both parties are still mired in partisan battles over other aspects of Obamacare – most notably how to protect people with pre-existing conditions and how to make insurance more affordable, particularly for people who buy coverage on their own.

That leaves American health care consumers with high premiums, big deductibles and skyrocketing out-of-pocket costs for drugs and other services. Neither party has a long-term solution — and the renewed fight over Obamacare that burst out over the past 10 days has made compromise even more elusive.

Democrats want to improve the 2010 health law, with more subsidies that shift costs to the taxpayer. Republicans are creating lower-cost alternatives to Obamacare, which means shifting costs to older and sicker people.

Neither approach gets at the underlying problem — reducing costs for both ordinary people and the health care burden on the overall U.S. economy.

Senate HELP Committee chair Lamar Alexander, the retiring Tennessee Republican with a reputation for deal-making, has reached out to think tanks and health care professionals in an attempt to refocus the debate, saying the interminable fights about the Affordable Care Act have “put the spotlight in the wrong place.”

“The hard truth is that we will never get the cost of health insurance down until we get the cost of health care down,” Alexander wrote, soliciting advice for a comprehensive effort on costs he wants to start by summer.

But given the partisanship around health care — and the fact there have been so many similar outreaches over the years for ideas, white papers and commissions — it’s hard to detect momentum. Truly figuring how to fix anything as vast, complex and politically charged as health care is difficult. Any serious effort will create winners and losers, some of whom are well-protected by powerful K Street lobbies.

And the health care spending conversation itself gets muddled. People’s actual health care bills aren’t always top of mind in Washington.

“Congress is looking at federal budgets. Experts are looking at national health spending and the GDP and value. And the American people look at their own out-of-pocket health care costs and the impact it has on family budgets,” said Drew Altman, the president and CEO of the Kaiser Family Foundation, which extensively tracks public attitudes on health.

But Congress tends to tinker around the edges — and feud over Obamacare.

“We’re doing nothing. Nothing. We’re heading toward the waterfall,” said former CBO director Doug Elmendorf, now the dean of the Harvard Kennedy School, who sees the political warfare over the ACA as a “lost decade,” given the high stakes for the nation’s economic health.

The solutions championed by the experts — a mix of pricing policies, addressing America’s changing demographics, delivering care more efficiently, creating the right incentives for people to use the right care and the smarter use of high-cost new technologies — are different than what the public would prescribe. The most recent POLITICO-Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health poll found the public basically wants lower prices, but not a lot of changes to how — or how much — they consume health care, other than spending more on prevention.

Lawmakers are looking at how to start chipping away at high drug prices, or fix “surprise” medical bills that hit insured people who end up with an out-of-network doctor even when they’re at an in-network hospital. Neither effort is insignificant, and both are bipartisan. While those steps would help lower Americans’ medical bills, health economists say they won’t do enough to reverse the overall spending trajectory.

Drug costs and surprise bills, which patients have to pay directly, “have been a way the public glimpses true health care costs,” said Melinda Buntin, chair of the Department of Health Policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “That information about how high these bills and these charges can be has raised awareness of health care costs — but it has people focused only on that part of the solution.”

And given that President Donald Trump has put Obamacare back in the headlines, the health law will keep sucking up an outsized share of Washington’s oxygen until and quite likely beyond the 2020 elections.

Just in the last week, the Justice Department urged the courts to throw out Obamacare entirely, two courts separately tossed key administration policies on Medicaid and small business health plans, and Trump himself declared he wants the GOP to be the “party of health care.” Facing renewed political pressure over the party’s missing Obamacare replacement plan, Trump last week promised Republicans would devise a grand plan to fix it. He backtracked days later and said it would be part of his second-term agenda.

Democrats say Trump’s ongoing assaults on the ACA makes it harder to address the big picture questions of cost, value and quality. “That’s unfortunately our state of play right now,” said Rep. Raul Ruiz (D-Calif.). “Basic health care needs are being attacked and threatened to be taken away, so we have to defend that.”

The ACA isn’t exactly popular; more than half the country now has a favorable view of it, but it’s still divisive. But for Republicans and Democrats alike, the new POLITICO-Harvard poll found the focus was squarely on health care prices — the cost of drugs, insurance, hospitals and doctors, in that order.

The Republicans’ big ideas have been to encourage less expensive health insurance plans, which are cheaper because they don’t include the comprehensive benefits under Obamacare. That may or may not be a good idea for the young and healthy, but it undoubtedly shifts the costs to the older and sicker. The GOP has also supported spending hundreds of millions less each year on Medicaid, which serves low-income people — but if the federal government pays less, state governments, hospitals and families will pay more.

Last week, courts blocked rules in two states that required many Medicaid enrollees to work in order to keep their health benefits, and also nixed Trump’s expansion of association health plans, which let trade groups and businesses offer coverage that doesn’t include all the benefits required under the ACA.

House Democrats last week introduced a package of bills that would boost subsidies in the Obamacare markets and extend that financial assistance to more middle-class people. The legislation would also help states stabilize their insurance markets — something that the Trump administration has also helped some states do through programs backstopping health insurers’ large costs.

These ideas may also bring down some people’s out-of-pocket costs, which indirectly lets taxpayers pick up the tab. These steps aren’t meaningless — more people would be covered and stronger Obamacare markets would stabilize premiums — but they aren’t an overall fix.

The progressive wing of the Democratic party backs “Medicare for All,” a brand new health care system that would cover everyone for free, including long-term care for elderly or disabled people. Backers say that the administrative simplicity, fairness, and elimination of the private for-profit insurance industry would pay for much of it.

The idea has moved rapidly from pipe dream to mainstream, but big questions remain even among some sympathetic Democrats about financing and some of the economic assumptions, including about how much of a role private insurance plays in Medicare today, and how much Medicare puts some of its costs onto other payers. Already a political stretch, the idea would face a lot more economic vetting, too.

The experts, as well as a smattering of politicians, define the health cost crisis more broadly: what the country spends. Health care inflation has moderated in recent years; backers of the Affordable Care Act say the law has contributed to that. But health spending is still growing faster than the overall economy. CMS actuaries said this winter that if current trends continue, national health expenditures would approach nearly $6 trillion by 2027 — and health care’s share of GDP would go from 17.9 percent in 2017 to 19.4 percent by 2027. There aren’t a lot of health economists who’d call that sustainable.

And ironically, the big fixes favored by the health policy experts — the ones that Alexander is collecting but most politicians are ignoring — might address many of the problems that keep aggravating U.S. politics. If there were rational prices that reflected the actual value of care provided for specific episodes of illness and treatment, instead of the fragmented system that largely pays for each service provided to patients, then no medical bill would be a surprise, noted Mark McClellan, who was both FDA and CMS chief under the President George W. Bush and now runs the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy.

“But taking those steps take time and will be challenging,” McClellan noted. “And they’ll be resisted by a lot of entrenched forces.”

Philadelphia-based Hahnemann University Hospital plans to lay off 175 nurses, support staff and managers as it struggles to keep its doors open, hospital officials told philly.com.

“We are in a life-or-death situation here at Hahnemann,” said Joel Freedman, chairman and founder of American Academic Health System, which bought Hahnemann and St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children from Dallas-based Tenet Healthcare in January 2018.

“We’re not Tenet with endless cash. We’re running out of money,” Mr. Freedman added.

He told philly.com Hahnemann won’t stay afloat without help from government, insurers and its academic partner, Philadelphia-based Drexel University.

The layoffs, which represent about 6 percent of Hahnemann’s total workforce of 2,700, reportedly affect 65 nurses, 22 service and technical employees, and 88 nonunion workers and managers.

They come as Hahnemann has struggled financially. The hospital and and St. Christopher’s combined have $600 million to $700 million in annual revenue, compared to $790 million at the time of American Academic Health System’s purchase, according to philly.com.

Mr. Freedman, who is also CEO of healthcare investment firm and American Academic Health System affiliate El Segundo-based Paladin Healthcare, partially attributed the struggles at Hahnemann to a lower volume of patients. He also cited information technology and documentation problems at the hospital.

He expects the layoffs, along with other cost-cutting initiatives, such as the closure of some primary care offices, to save Hahnemann $18 million annually.

Read the full philly.com report here.

Healthcare workers at Los Angeles-based Cedars-Sinai Medical Center revealed a series of billboards that highlights profits and CEO pay at the hospital.

The workers, who are represented by Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West, announced the billboards April 2 amid contract negotiations. The billboards are scheduled to appear throughout April at seven locations that are all within 1.5 miles of the hospital.

A union news release says the billboards aim to draw attention to “excessive profits and CEO compensation,” as well as the amount of charity care the nonprofit hospital provides.

“The public deserves to know that this elite hospital with huge profits and obscene CEO compensation, isn’t acting in the public’s best interests,” Dave Regan, president of SEIU-UHW, said in the release. “On top of paying no income or property taxes, Cedars-Sinai skimps when it comes time to care for the poorest people in our community.”

The hospital addressed the union’s claims.

“The Cedars-Sinai Board of Directors believes in providing every one of our employees with compensation that is based upon merit of their individual performance, a rigorous review of each position’s responsibilities, and comparisons with other organizations for positions with similar responsibilities. For the president and CEO, the review process is even more extensive,” the statement said.

“[CEO]Tom Priselac’s compensation appropriately reflects his more than two-decade tenure of successfully presiding over the western United States’ largest nonprofit hospital. Under his leadership, Cedars-Sinai has earned national recognition for delivering the highest quality care to patients and has been ranked among the top medical centers in the country.

“Over the last 10 years alone, Cedars-Sinai has invested nearly $6 billion to benefit the local community by, among other things, providing free or part-pay care for patients who cannot afford treatment; by losses caring for Medicare and Medi-Cal patients; and by providing a wide range of free health programs and clinics in neighborhoods as well as education, health and fitness services in dozens of local schools.”

SEIU-UHW represents more than 1,800 service and technical workers at the hospital. The last contract with Cedars-Sinai expired March 31.

The only plausible explanation for President Trump’s renewed effort through the courts to do away with the Affordable Care Act, other than muscle memory, is a desire to play to his base despite widely reported misgivings in his own administration and among Republicans in Congress.

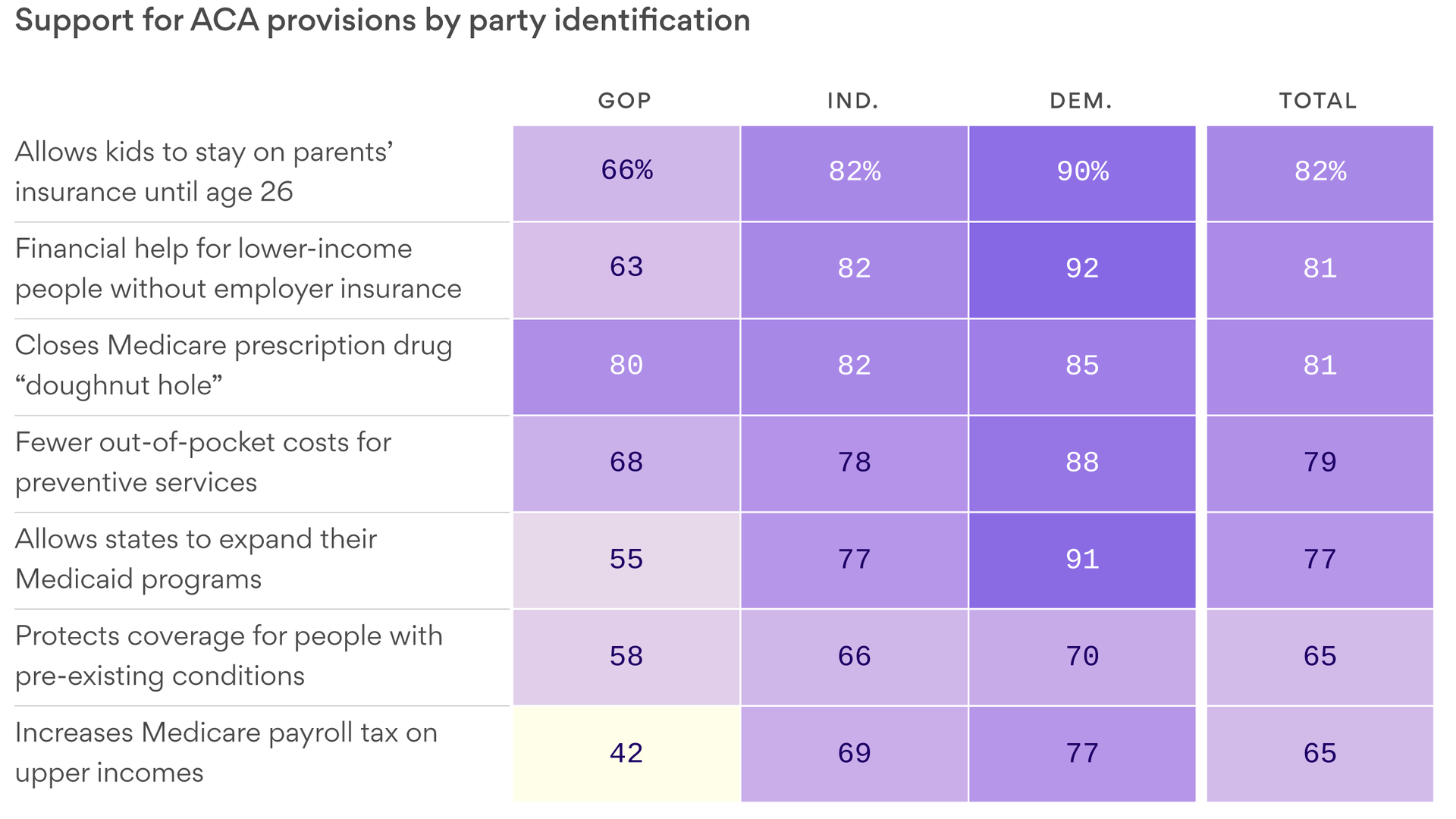

Reality check: But the Republican base has more complicated views about the ACA than the activists who show up at rallies and cheer when the president talks about repealing the law. The polling is clear: Republicans don’t like the ACA, but just like everyone else, they like its benefits and will not want to lose them.

GOP leaders are trying their best to put a lid on President Trump’s talk of a new and wonderful health care plan that would define the Republican Party for 2020.

“Not any longer,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said yesterday when asked whether he and Trump differ on health care.

Rhetorically, Trump has kicked the can past 2020, just after pushing his administration to dive back into — and escalate — the legal fight that hurt Republicans so badly in 2018.

Reality check: It’s still the Justice Department’s position that the courts should strike down the Affordable Care Act. As long as this lawsuit is still active — and that will be a while — it’ll be accurate for Democrats to say on the campaign trail that Trump is trying to end protections for pre-existing conditions.

Together with Jonathan Adler, Abbe Gluck, and Ilya Somin, I’ve filed an amicus brief with the Fifth Circuit in Texas v. Azar. Those of you who’ve been closely following health-reform litigation know that Abbe and I often square up against Jonathan and Ilya. It’s a testament to the outlandishness of the district court’s decision that we’ve joined forces. Like our original district court filing, the brief focuses on severability.

In 2017, Congress zeroed out all the penalties the ACA had imposed for not satisfying the individual mandate. Yet it left everything else undisturbed, including the guaranteed-issue and community-rating provisions. That simple fact should be the beginning and end of the severability analysis. It was Congress, not a court, that made the mandate unenforceable. And when Congress did so, it left the rest of the scheme, including those two insurance reforms, in place. In other words, Congress in 2017 made the judgment that it wanted the insurance reforms and the rest of the ACA to remain even in the absence of an enforceable individual mandate.

Because Congress’s intent was explicitly and duly enacted into statutory law, consideration of whether the remaining parts of the law remain “fully operative”—an inquiry courts often use in severability analysis as a proxy for congressional intent—is unnecessary.

Nor does the district court’s incessant focus on findings that Congress made about a mandate backed by financial penalties hold water.

The 2010 Congress believed that 2010’s penalty-backed mandate was necessary to induce a significant number of healthy people to purchase insurance, and thereby “significantly reduc[e] the number of the uninsured.” 42 U.S.C. § 18091(2)(E). But because the neutered mandate of 2017 lacks a penalty, it could not have been based on those earlier findings. They are thus irrelevant. The earlier findings have been overtaken by Congress’s developing views—based on years of experience under the statute—that the individual marketplaces created by the ACA can operate without penalizing Americans who decline to purchase health insurance.

At bottom, a toothless mandate is essential to nothing. A mandate with no enforcement mechanism cannot somehow be essential to the law as a whole. That is so regardless of the finer points of severability analysis or congressional intent. The district court’s conclusion makes no sense.

There are (at least!) two other notable amicus briefs in the case.

The first is from Sam Bray, Michael McConnell, and Kevin Walsh. In a terse 1,000 words, they argue—correctly, in my view—that “Congress has not vested the federal courts with statutory subject-matter jurisdiction to opine whether an unenforceable statutory provision is unconstitutional.” In this, they sound many of the same themes that Jonathan Adler and yours truly sounded in arguing that plaintiffs lack standing under the Constitution. But Bray, McConnell, and Walsh hitch their argument not to Article III, but to the jurisdictional reach of the Declaratory Judgment Act.

The second is from the Republican attorneys general of Ohio and Montana. They agree that the mandate is unconstitutional, but they have no truck with the argument that all or part of the Affordable Care Act should be struck down. “At the same time that Congress made the mandate inoperative, it left in place the remainder of the Affordable Care Act. As a result, the application of the severability doctrine in this case requires no ‘nebulous inquiry into hypothetical congressional intent.’ … To the contrary, the Court can see for itself what Congress wanted by looking to what it did.” Their participation suggests deep fractures in the down-with-the-ACA-at-all-costs coalition.

So, by my count, the parties and amici have pressed at least four independent reasons for getting rid of this case. First, because plaintiffs lack standing. Second, because the courts lack jurisdiction under the Declaratory Judgment Act. Third, because there is no “mandate” and thus no constitutional problem (as Marty Lederman has rightly argued). And fourth, because even if there is a mandate and it’s unconstitutional, it’s fully severable.

This isn’t a federal case. It’s a choose-your-own-adventure book where all the adventures lead to the end of this misbegotten litigation.

Cumberland, Md.-based Western Maryland Health System has signed a nonbinding letter of intent with Pittsburgh-based UPMC to pursue a merger.

The systems entered a clinical affiliation in February 2018. Over the next few months they will engage in further due diligence and research to reach a definitive merger agreement.

A merger would “allow WMHS to maintain clinical excellence in western Maryland and throughout the region for years to come,” said Barry Ronan, president and CEO of the Maryland health system. “Since we became clinically affiliated with UPMC in 2018, we have a stronger clinical and operational position, allowing a broad range of nationally recognized care here locally for the people of Allegany County and surrounding counties in Maryland, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.”