https://revcycleintelligence.com/features/patient-financial-experience-the-new-focus-for-revenue-cycle-tech?eid=CXTEL000000093912&elqCampaignId=8479&elqTrackId=be91ef7e45814e448e63f5f449863c07&elq=c0883462d36f46f1919e194284b0fcd0&elqaid=8937&elqat=1&elqCampaignId=8479

Hospitals and practices have traditionally relied on public and private payers to cover the bulk of patient charges and costs for their services. Everything from their revenue cycle technologies to billing workflows has been tailored to create cleaner claims, reduce denials, and collect payer reimbursement.

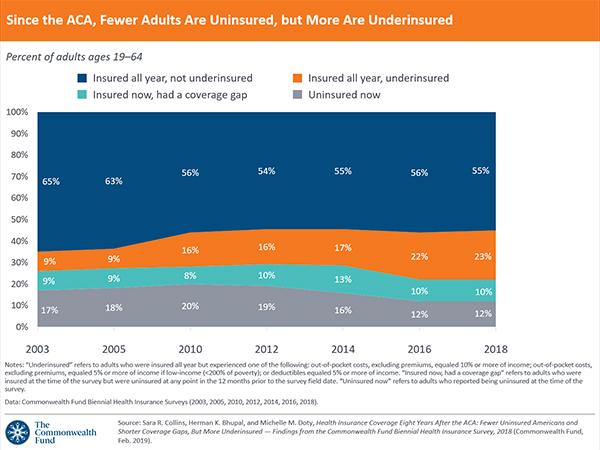

But in an environment of record spending and changing attitudes towards purchasing and payment, payers are starting to shift more financial responsibility to their consumers. Nearly 21 million Americans had a high-deductible health plan or health savings account in 2017, and AHIP experts anticipate enrollment in high-deductible plans to continue climbing.

Increases in patient out-of-pocket spending are driving individuals to become more discerning healthcare consumers who demand more value for the medical services they receive. Plans and policymakers argue that the rise in healthcare consumerism will ultimately result in lower cost, higher quality care.

In the meantime, however, high-deductible health plans and other increases in out-of-pocket spending are presenting challenges to providers who are not used to this new player: the patient as a payer.

Three-quarters of providers report that they are seeing a noticeable upward trend in what patients must pay out of pocket. At hospitals, total revenue attributable to patient balances after insurance rose 88 percent from 2012 to 2017.

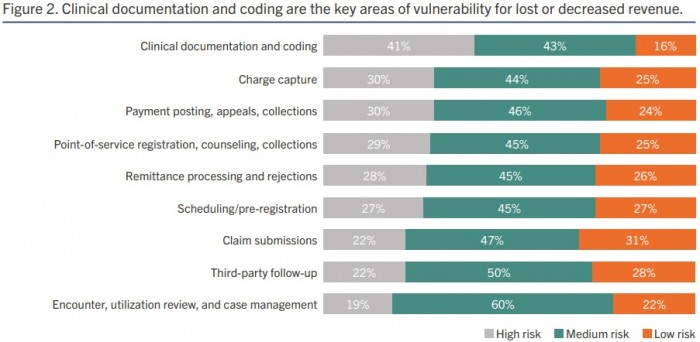

While payers have been steadily shifting the financial responsibility to consumers, providers have yet to adapt their workflows and systems to collect revenue from this new source while delivering a satisfactory experience to consumers.

For example, nearly all 900 healthcare financial executives recently surveyed by HIMSS Analytics said their organizations still use paper-based billing and collection strategies – despite the fact that the same survey revealed more than half of patients prefer electronic billing methods.

Patients in the survey even said they were more likely to pay their medical bills if they had the option to do so online.

In light of these statistics, providers are facing the difficult task of transforming their manual patient collection processes to address this changing, consumer-focused trend.

“What we’ve seen historically has been that the revenue cycle has been not as well funded or not as strategically prioritized for healthcare delivery networks. A lot of the decision making has been either reactive or more short-term oriented,” Joe Polaris, Senior Vice President of Product and Technology at the health IT company R1 RCM, recently told RevCycleIntelligence.com.

“But we’re starting to see more of a long-term strategic vision coming together for their revenue cycles,” he added. “Organizations understand they need to make transformative change in light of some of the challenges that are only growing in the market, especially the need to be consumer-friendly.”

Revenue cycle technologies that cater to the patient financial experience are part of that transformative change, added Matt Hawkins, the CEO of Waystar, the newly combined revenue cycle management company formed by ZirMed and Navicure.

“Innovators are beginning, more so than ever, to treat the patient as a consumer,” he said. “A lot of health systems are demanding or embracing services or technologies that get them closer to patients from the earliest interaction point.”

The demand for technologies that cater to the patient financial experience is on the rise. And providers could face significant financial losses and patient retention problems if they fail to adapt to healthcare consumerism.

Becoming a patient-centered entity that can collect what it’s owed without alienating its consumers is a significant challenge, experts agree. But embracing a handful of high-impact strategies could help to ensure that both patients and their providers complete the payment process feeling satisfied.

PRICE TRANSPARENCY LAYS THE FOUNDATION FOR PATIENT FINANCIAL EXPERIENCE

“Consumerism” may be a popular buzzword in the healthcare industry, but providers still have a long way to go before their patients can accurately compare their clinical journeys to their retail experiences.

For one thing, patients often agree to services or procedures with no clear idea of what they will ultimately cost.

Providers rarely offer prices or price estimates to patients prior to service delivery. In fact, the percentage of hospitals that are not able to give consumers price estimates actually increased from 14 percent in 2012 to 44 percent in 2018, a recent JAMA Internal Medicine study revealed.

With patients expecting the ability to plan their expenses, providers are looking to implement new revenue cycle technologies that can deliver accurate cost estimates and boost overall healthcare price transparency.

“How do we give patients shoppable experiences, so they can find out the cost of an MRI?” asked Christy Martin, Senior Vice President of Product Management at Optum360. “In their local care market, where is the best place to go in terms of both quality and cost? Then, if they go to a certain location, what are they expected to pay based on their insurance coverage? What would the out-of-pocket costs be at this point in the year?”

Informing consumers of their patient financial responsibility before the point-of-service is critical for providers seeking to improve the patient financial experience.

“In the immediate future, one of the things that we can unlock using technology is an understanding upfront about what the payment responsibility will be, and have that help inform all of the things that happen subsequent to presenting that to the patient,” Hawkins said.

Providing price estimates up front helped one health system in Oklahoma increase point-of-service collections by $17 million in seven years.

The Consumer Priceline tool at INTEGRIS Health is a database of charges for most procedures and services. The health system also promises to deliver written price quotes to consumers within two days if the service is not already included in the database.

INTEGRIS may be seeing significant patient collection improvements using price estimates, but providers should be aware that databases like the Consumer Priceline tool require a wealth of historical financial data.

“In the immediate future, one of the things that we can unlock using technology is an understanding upfront about what the payment responsibility will be.”

Merely posting chargemaster prices for common services and procedures is not necessarily helpful for patients. Giving consumers information about their patient financial responsibility and out-of-pocket costs is supposed to prevent sticker shock. Yet chargemaster prices are primarily used to start negotiations with payers, and the numbers can seem exorbitant to consumers.

“Chargemaster prices serve only as a starting point; adjustments to these prices are routinely made for contractual discounts that are negotiated with or set by third-party payers. Few patients actually pay the chargemaster price,” the Healthcare Financial Management Association (HMFA) explained to policymakers in May 2018.

Despite reservations about chargemaster prices, CMS recently required hospitals to publish a list of their standard charges online. And providers are scrambling to understand how to present the information in a meaningful way to consumers.

About 92 percent of providers in a recent poll said they were concerned about the new hospital price transparency requirement, and the majority also expressed concerns about how the public would perceive their standard charges.

Now more than ever, revenue cycle technologies that aggregate and analyze information on what patients actually pay will be critical for health systems.

UNIFYING THE PATIENT FINANCIAL EXPERIENCE

Healthcare is nothing like going grocery shopping. Not only do consumers not have access to prices, but the funding mechanism for medical services is also vastly different from a traditional retail experience.

Unlike what happens during a retail transaction, healthcare consumers rarely pay providers directly for services or procedures rendered. Instead, healthcare consumers use insurance plans, health savings accounts, and a wide range of other funding mechanisms to eventually pay providers after a service is delivered. They may also receive several bills and benefit documents from providers and insurers before receiving the final bill listing their financial responsibility.

As patients become more responsible for their healthcare spend, the onus is on providers to simplify the patient financial experience if they want to boost collections and save their bottom line.

Delivering a navigable and consistent financial experience is key to making the most of the newly consumer-driven environment, Polaris advised providers.

“The patient wants to have a clear and transparent journey through the healthcare system, and that’s much more challenging when they have to navigate different departments on different systems, asking for the same data over and over again, never coordinating, and never communicating a holistic end-to-end experience,” he said.

Integrated and seamless revenue cycle technologies aim to deliver a consistent patient financial experience by simplifying medical bills and bringing all providers in a practice, hospital, or health system under the same billing brand.

For example, a multi-specialty physician group in central Texas boosted patient collections by 24 percent and reduced the amount of patient cash sitting in A/R from 14 to two percent in one year by unifying the patient financial experience across their organization.

“Even though we were one clinic with 60 providers, our collection process treated every healthcare encounter separately,” explained Abilene Diagnostic Clinics CFO Andrew Kouba, CPA. “Patients were receiving bills for each physician they saw, which allowed them to pick and choose which bills to pay. When you get four statements and you think you got one experience, you’re confused as a patient.”

Consolidating all of Abilene’s providers under one billing system helped the group to deliver a consistent patient financial experience, which in turn simplified the payment process for consumers.

Revenue cycle departments are finding that end-to-end systems or interoperable bolt-on solutions are worth the investment. The integrated technologies allow healthcare organizations to guide the patient through the financial experience.

But to truly advance the patient financial experience, revenue cycle technology experts agreed that clinical and financial data integration is also vital.

“Being able to leverage the clinical and billing data to provide a better patient experience all the way around is a key capability,” Martin of Optum360 stated.

“While hospitals are certainly focused on providing high-quality care, there’s also this focus on how they can improve the overall patient financial experience to reduce the confusion, complexity, and lack of understanding around patient responsibility. Health systems are looking to provide ease of doing business to address patient responsibility and reduce patient bad debt.”

Revenue cycle technologies that can leverage both clinical and financial data are crucial to transforming the patient experience into a consumer-friendly encounter. Understanding the whole patient can help providers offer a consistent experience from the front office to the billing department.

SELF-SERVICE AS THE ULTIMATE PATIENT FINANCIAL EXPERIENCE GOAL

Price transparency tools and integrated revenue cycle technologies lay the groundwork for a consistent, intuitive patient financial experience. But revenue cycle technology vendors are also observing an increased interest in self-service portals and kiosks for the ultimate retail-like experience.

The disjointed, manual processes involved in the patient financial experience have not been convenient for consumers. Patients often have to interact with a call center or sit down with a staff member to complete basic tasks like scheduling, filling out insurance forms, or paying a medical bill, Polaris explained. In other industries, these tasks have already been replaced by mobile apps or automated systems.

“With digital self-service, we automate tasks like they do in the airline industry,” he said. “We let the patient book an appointment right on their mobile phone, get all the paperwork, fill out the forms they need, and check in at a kiosk.”

“Automation takes repetitive tasks that are frankly not patient- or consumer-friendly out of the process and makes the whole healthcare experience much more satisfying,” he stressed.

Self-service portals and kiosks have the potential to truly transform the patient financial experience into a more convenient, navigable journey. But healthcare organizations would need to invest in large amounts of revenue cycle automation to achieve this goal, Polaris acknowledged.

“Automation takes a lot of forms,” he explained. “There’s always been robotics, user emulation, and basic automation to complete individual tasks. But very few organizations have driven automation of entire processes, and that’s where we’re seeing more investment in transformative automation.”

Healthcare consumers have already voiced their support for more self-service options and more automation. A recent survey of over 500 individuals showed that in addition to offering more payment options and sending simpler bills, expanding access to self-service tools was a top suggestion for improving the patient financial experience.

“Automation takes repetitive tasks that are frankly not patient- or consumer-friendly out of the process and makes the whole healthcare experience much more satisfying.”

Providers are also expressing interest in implementing the relatively new technology in the revenue cycle space. Kouba from Abilene Diagnostic Clinic in Texas said he wanted to create a type of Disney FastPass for the patient financial experience.

“We want to simplify the process from pre-registration through bill collection and try to automate that similar to Disney’s FastPass,” Kouba stated. “Disney is one of the best experiences of all time and when you go there, they want you to interact with the people, all their products, and just enjoy yourselves. The last thing Disney wants you to think of is the terrible lines.”

“If we can remove the pain points and strive to ease that front piece, the patient will be focused on a friendly conversation when they walk in the door with the person that can answer questions, rather than being pestered to pull out their wallet.”

However, Kouba is not convinced that full automation will take over the healthcare industry any time soon.

As much as adopting retail-style approaches can improve the patient financial journey, providers must still ensure their technologies and processes work for them, too.

For example, Kouba decided that self-service technology that automates scheduling is not ideal for Abilene.

“In our group, most of our physicians like to follow their patients to the hospital, so the difficult piece with self-scheduling, especially from the provider’s side, is their schedules depend on what their rounds look like for the day. It’s very difficult to get them to commit to blocks of time,” he continued.

Self-service and automated tools may still be maturing in the revenue cycle technology space. But providers still have the option to improve the patient financial experience through systems that estimate patient financial responsibility and unify the billing experience.

And providers should be looking to the revenue cycle technology market for help. The rise of patient financial responsibility has been steady. Deductibles and out-of-pocket costs have been growing, particularly since healthcare spending growth rates rapidly accelerate.

Implementing the right tools for their patients and their providers will be key to empowering patients to choose the highest value care while ensuring providers get paid for it.