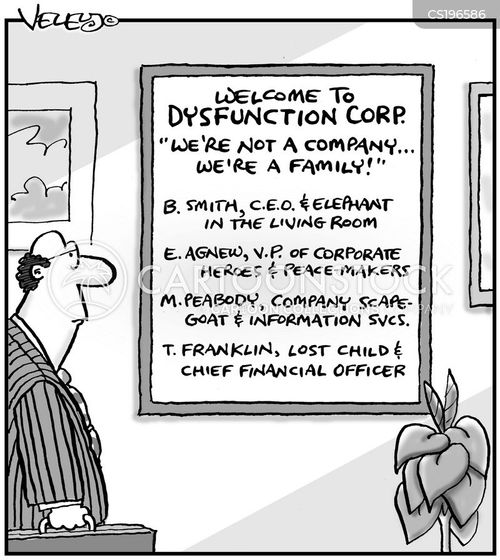

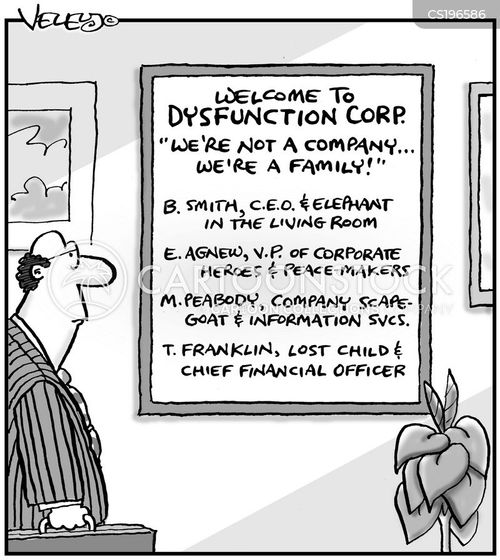

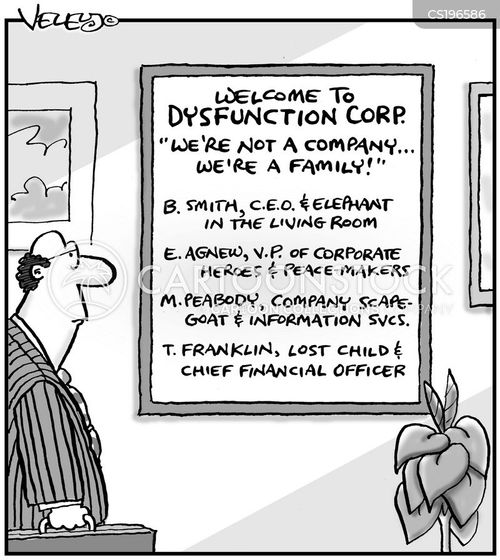

Cartoon – Welcome to Dysfunctional Corp.

Conservative demonstrators gathered at the capitol buildings of Michigan, Kentucky, and North Carolina to protest against stay-at-home orders during a pandemic that has already left more than 26,000 Americans dead.

“I am posting, for once, about something other than my dog.

I have seen 4 patients die, 5 get intubated, 2 re-intubated, witnessed family consent to make 2 more patients DNRs, sweat my butt off during CPR, titrated so many drips to no avail, watched vent settings increase to no avail. We are exhausted and at a total loss.

All of this in two shifts in a row.

Some of you people have never done EVERYTHING you could to save someone, and watched them die anyway, and it shows.

I would have no problem if you fools worried about your “freedom” all went out and got COVID. If only you could sign a form stating that you revoke your right to have medical treatment based on your cavalier antics and refusal to abide by CDC and medical professionals’ advice. If you were the only people who got infected during your escapades to protest tyranny, great. But that’s sadly not how this works.

You wanna complain because the garden aisle is closed? If you knew a thing about gardening, you’d know it’s too early to plant in Michigan. Your garden doesn’t matter. If killing your plants would bring back my patients, I would pillage the shit out of your “essential” garden beds.

Upset because you can’t go boating…in Michigan…in April…in the cold-ass water? You wanna tell my patient’s daughter (who was sobbing as she said goodbye to her father over the phone) about your first-world problems?

Upset because you can’t go to your cottage up north? Your cottage…your second property…used for leisure. My coworkers can’t even stay in their regular homes. Most have been staying in hotels and dorms, not able to see their spouses or babies.

All of these posts, petitions online to evade “tyranny”, it’s all such bullshit. I’m sorry you’re bored and have nothing to do but bitch and moan. You wanna pick up a couple hours for me? Yeah, didn’t think so. I wouldn’t trust most of you with patient care, anyway. Not just because of the selfish lack of humanity your posts exude, but because most of those posts and petitions are so riddled with misspellings and grammatical errors, that it makes me question your cognitive capacity.

Shoutout to my coworkers, the real MVPs.”

As sweeping stay-at-home orders in 42 U.S. states to combat the new coronavirus have shuttered businesses, disrupted lives and decimated the economy, some protesters have begun taking to the streets to urge governors to rethink the restrictions.

A few dozen protesters, many with young children, gathered in Virginia’s state capital of Richmond on Thursday in defiance of Democratic Governor Ralph Northam’s mandate, the latest in a series of demonstrations this week around the country.

The protests have taken on a partisan tone, often featuring supporters of President Donald Trump, and critiquing governors whose shelter-at-home directives are intended to slow the spread of a pandemic that has killed more than 31,000 across the United States.

On Wednesday, thousands of Michigan residents blocked traffic in Lansing, the state capital, while protesters in Kentucky disrupted Democratic Governor Andy Beshear’s afternoon news briefing on the pandemic, chanting “We want to work!”

States including Utah, North Carolina and Ohio also saw demonstrations this week, and more are planned for the coming days, including in Oregon, Idaho and Texas.

The United States has seen the highest death toll of any country in the pandemic, and public health officials have warned that a premature easing of social distancing orders could exacerbate it.

Trump has repeatedly said he wants to “reopen” the economy as soon as possible and has clashed with governors over whether he can overrule their stay-at-home orders.

In Michigan, where Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer has imposed some of the country’s toughest limits on travel and business, some protesters at “Operation Gridlock” wore campaign hats and waved signs supporting Trump.

Whitmer is considered a top contender to be the running mate of Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden when he takes on Trump in November’s general election.

One of the organizers of the demonstration in Lansing, Meshawn Maddock, said she was frustrated that much of the media focused on a handful of protesters who gathered on the steps of the capitol, including militia group members and a man holding a Confederate flag who she said were not part of the rally.

She faulted Whitmer for dismissing the event as a partisan rally instead of engaging with the thousands of residents who Maddock said have legitimate questions about the governor’s stay-at-home order.

“When I’m fighting to (help) a guy who cleans pools or mows lawns, or a women who wants to sell her onion sets or geraniums, I don’t care whether they vote Republican, Democrat, or never vote at all,” Maddock said.

Maddock, 52, is among seven board members of the Republican-aligned Michigan Conservative Coalition who organized the protest. She is also a board member of the pro-Trump political action committee Women for Trump, but said the Trump campaign had no involvement in organizing the protest.

“The Trump campaign has given me no messaging,” she said. “All I know is that I care about Michigan. I’ve lived here my whole life and I want to help workers get back to work.”

She said she had received calls from people in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Virginia and other states asking for advice on planning similar protests.

The political wrangling over the COVID-19 crisis has begun to take on familiar partisan battle lines. Democratic strongholds in dense urban centers such as Seattle and Detroit have been hard hit by the virus, while more Republican-leaning rural communities are struggling with the shuttered economy but have seen fewer cases.

Kenny Clevenger, 30, a realtor in western Michigan’s Allegan County, where only 25 coronavirus cases have been identified, said the shutdown had put him out of business.

“Yes, this needs to be taken seriously, but it’s being taken advantage of,” Clevenger said. “People believe Democrats are attempting to use this to undermine the economy, once again just attacking the president.”

Increasingly, Republican state lawmakers, including some in Texas, Oklahoma and Wisconsin, have begun putting pressure on governors to reopen businesses. Pennsylvania’s Republican-led legislature passed a bill that would loosen restrictions, which Democratic Governor Tom Wolf was expected to veto.

Both Democratic and Republican governors have resisted calls to abandon distancing too quickly. On Thursday, five Democratic governors and two Republican governors in the Midwest, including Whitmer in Michigan, said they would coordinate efforts.

Stephen LaSpina, one of the organizers of a “Stand Up to End the Shutdown” protest set for April 20 at Pennsylvania’s capitol in Harrisburg said that its sole goal was to get the economy running again by May 1.

“We are really welcoming groups of all different backgrounds and demographics,” said LaSpina, who lives near Scranton, and like many others who work in retail, said he had personally been affected by the shutdown. “Anyone who has been impacted by this shutdown in a negative way is welcome and we want them to be heard regardless of their party affiliation.”

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2020/3/31/21199874/coronavirus-spanish-flu-social-distancing

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66580807/2660331.jpg.0.jpg)

A study of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic finds that cities with stricter social distancing reaped economic benefits.

For much of the past month, some commentators have defended the effort to promote social distancing, including the near-shutdown of huge swaths of America’s economy, as the lesser of two evils: Yes, asking or forcing people to remain in their homes for as much of the day as possible will slow economic activity, the argument goes. But it’s worth it for the public health benefits of slowing the coronavirus’s spread.

This argument has, naturally, led to a backlash, explained here by my colleague Ezra Klein. Critics — including the president — have argued that the cure is worse than the disease, and mass death from coronavirus is a price we need to be willing to pay to keep the American economy from cratering.

Both these viewpoints obscure an important possibility: The social distancing regime may well be optimal not just from a public health point of view, but from an economic perspective as well.

Economists Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner released a working paper (not yet peer-reviewed) last week that makes this argument extremely persuasively. The three analyzed the 1918-1919 flu pandemic in the United States, as the closest (though still not identical) analogue to the current crisis. They compare cities in 1918-’19 that adopted quarantining and social isolation policies earlier to ones that adopted them later.

Their conclusion? “We find that cities that intervened earlier and more aggressively do not perform worse and, if anything, grow faster after the pandemic is over.”

The researchers refer to such social distancing policies as NPIs, or “non-pharmaceutical interventions,” essentially public health interventions not achieved through medication, like quarantines and school and business closures. The key to the paper is their observation that, in theory, NPIs can both decrease economic activity directly, by keeping people in certain jobs from going to work, and increase it indirectly, because it prevents large-scale deaths that would also have a negative impact on the economy.

“While NPIs lower economic activity, they can solve coordination problems associated with fighting disease transmission and mitigate the pandemic-related economic disruption,” they write. In other words, social distancing measures that save lives can also, in the end, soften the economic disruption of a pandemic.

The data here comes from a 2007 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association, where a group of researchers chronicled what specific policies were put in place between September 8, 1918, and February 22, 1919, by 43 different cities. The most common NPI the JAMA researchers identified was a combination of school closures and bans on public gatherings; 34 of the 43 cities adopted this rule, for an average of four weeks.

Other cities eschewed these policies in favor of mandatory isolation and quarantine procedures: “Typically, individuals diagnosed with influenza were isolated in hospitals or makeshift facilities, while those suspected to have contact with an ill person (but who were not yet ill themselves) were quarantined in their homes with an official placard declaring that location to be under quarantine,” the JAMA authors write, detailing New York City’s approach.

Another 15 cities did both isolation/quarantines and school closures/public gathering bans.

The 2007 paper found a strong association between the number and duration of NPIs and pandemic deaths, with more and longer-lasting NPIs associated with a smaller death toll. Correia, Luck, and Verner, in their new paper, replicate this finding.

But they take it a step further. They study the impact of changes in mortality due to the 1918 pandemic on economic outcomes.

“The increase in mortality from the 1918 pandemic relative to 1917 mortality levels (416 per 100,000) implies a 23 percent fall in manufacturing employment, 1.5 percentage point reduction in manufacturing employment to population, and an 18 percent fall in output,” they conclude. In other words, a big outbreak spelled economic disaster for affected cities.

Then they combined this analysis with an analysis of the effects of NPI policies. They find that the introduction of social distancing policies is associated with more positive outcomes in terms of manufacturing employment and output. Cities with faster introductions of these policies (one standard deviation faster, to be technical) had 4 percent higher employment after the pandemic had passed; ones with longer durations had 6 percent higher employment after the disaster.

The takeaway is clear: These policies not only led to better health outcomes, they in turn led to better economic outcomes. Pandemics are very bad for the economy, and stopping them is good for the economy.

It’s important to always approach this kind of study with a degree of skepticism. The 1918 pandemic was not a planned experiment, so researchers’ ability to determine the degree to which the pandemic, or the policies adopted in response to it, affected economic outcomes is always going to be somewhat limited.

The researchers acknowledge that their biggest limitation is the non-randomness of policy adoption by cities. Presumably cities with strict responses to the pandemic were different from cities with laxer responses in ways that went beyond this one incident. Maybe the stricter cities had better public health infrastructure to begin with, for instance, which could exaggerate the estimated effect of social distancing interventions.

The authors argue that because the second and most fatal wave of the 1918 pandemic spread mostly from east to west, geographically, these kinds of dynamics weren’t at play. “Given the timing of the influenza wave, cities that were affected later appeared to have implemented NPIs sooner as they were able to learn from cities that were affected in the early stages of the pandemic,” they note.

The best explanation of differences in policies, then, is how far a city is from the East Coast of the US. They control for a big factor that might affect Western states more (the boom and bust of the agricultural industry as World War I drew to a close) and find few other observable differences between Western cities with strong policies and Eastern policies with weak ones. But the notion that these cities are comparable is a key part of the paper’s research design, and one worth digging into as the paper goes through peer review and revisions.

The message that there isn’t a trade-off between saving lives and saving the economy is reassuring. If there were such a trade-off, the debate over coronavirus response would be in the realm of pure values: How much money should we be willing to forsake to save a human life? That’s a thorny choice, and finding that we don’t actually have to make it — as this paper suggests — is comforting.

It’s worth emphasizing, though, that if we did have to make that choice, it would still be an easy decision. The lives saved would be worth more.

In another recent white paper, UChicago’s Michael Greenstone and Vishan Nigam estimate the social value of social distancing policies, relative to a baseline where we endure an untrammeled pandemic. To simulate the two scenarios, they rely on the influential Imperial College London model of the coronavirus pandemic — a paper that found that an uncontrolled spread of coronavirus would kill 2.2 million Americans.

Then they throw in an oft-used tool of cost-benefit economic analysis: the value of a statistical life (VSL). Popularized by Vanderbilt economist Kip Viscusi, VSL involves putting a dollar value on a human life by estimating the implicit value that people in a given society place on continuing to live based on their willingness to pay for services that reduce their risk of dying.

Usually, this involves a “revealed preferences” approach. A 2018 paper by Viscusi, for example, used, among other data sources, Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries to measure how much more, in practice, US workers demand to be paid to take jobs that carry a higher risk of death.

Greenstone and Nigam allow VSL to vary with age — understandably, older people are less willing to pay to reduce their odds of death than younger people — but set the average VSL for an American age 18 and over to $11.5 million.

Based on the Imperial College projection that social distancing would save about 1.76 million lives over the next six months, Greenstone and Nigam estimate that the economic value of the policy is $7.9 trillion, larger than the entire US federal budget and greater than a third of GDP. The value is about $60,000 per US household. Even if the Imperial College model is off by 60 percent and the no-social-distancing scenario is less deadly than anticipated, the aggregate benefits are still $3.6 trillion. And this is likely an underestimate that ignores other costs of a large-scale outbreak to society; it focuses solely on mortality benefits.

VSL is sometimes attacked from the left as craven, a reductio ad absurdum of economistic reasoning trampling over everything, including the value of human life itself. But coronavirus helps illustrate how VSL can work in the opposite direction. Human life is so valuable in these terms that social distancing would have to force a 33 percent drop in US GDP before you could start to plausibly argue that the cure is worse than the disease.

That social distancing likely won’t cause a reduction in GDP relative to a scenario where there’s a multimillion-person death toll, as indicated by the 1918 flu paper, makes the case for distancing policies that much stronger.

STOCKHOLM – Does Sweden’s decision to spurn a national lockdown offer a distinct way to fight COVID-19 while maintaining an open society? The country’s unorthodox response to the coronavirus is popular at home and has won praise in some quarters abroad. But it also has contributed to one of the world’s highest COVID-19 death rates, exceeding that of the United States.

In Stockholm, bars and restaurants are filled with people enjoying the spring sun after a long, dark winter. Schools and gyms are open. Swedish officials have offered public-health advice but have imposed few sanctions. No official guidelines recommend that people wear masks.

During the pandemic’s early stages, the government and most commentators proudly embraced this “Swedish model,” claiming that it was built on Swedes’ uniquely high levels of “trust” in institutions and in one another. Prime Minister Stefan Löfven made a point of appealing to Swedes’ self-discipline, expecting them to act responsibly without requiring orders from authorities.

According to the World Values Survey, Swedes do tend to display a unique combination of trust in public institutions and extreme individualism. As sociologist Lars Trägårdh has put it, every Swede carries his own policeman on his shoulder.

But let’s not turn causality on its head. The government did not consciously design a Swedish model for confronting the pandemic based on trust in the population’s ingrained sense of civic responsibility. Rather, actions were shaped by bureaucrats and then defended after the fact as a testament to Swedish virtue.

In practice, the core task of managing the outbreak fell to a single man: state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell at the National Institute of Public Health. Tegnell approached the crisis with his own set of strong convictions about the virus, believing that it would not spread from China, and later, that it would be enough to trace individual cases coming from abroad. Hence, the thousands of Swedish families returning from late-February skiing in the Italian Alps were strongly advised to return to work and school if not visibly sick, even if family members were infected. Tegnell argued that there were no signs of community transmission in Sweden, and therefore no need for more general mitigation measures. Despite Italy’s experience, Swedish ski resorts remained open for vacationing and partying Stockholmers.

Between the lines, Tegnell indicated that eschewing draconian policies to stop the spread of the virus would enable Sweden gradually to achieve herd immunity. This strategy, he stressed, would be more sustainable for society.

Through it all, Sweden’s government remained passive. That partly reflects a unique feature of the country’s political system: a strong separation of powers between central government ministries and independent agencies. And, in “the fog of war,” it was also convenient for Löfven to let Tegnell’s agency take charge. Its seeming confidence in what it was doing enabled the government to offload responsibility during weeks of uncertainty. Moreover, Löfven likely wanted to demonstrate his trust in “science and facts,” by not – like US President Donald Trump – challenging his experts.

It should be noted, though, that the state epidemiologist’s policy choice has been strongly criticized by independent experts in Sweden. Some 22 of the country’s most prominent professors in infectious diseases and epidemiology published a commentary in Dagens Nyheter calling on Tegnell to resign and appealing to the government to take a different course of action.

By mid-March, and with wide community spread, Löfven was forced to take a more active role. Since then, the government has been playing catch-up. From March 29, it prohibited public gatherings of more than 50 people, down from 500, and added sanctions for noncompliance. Then, from April 1, it barred visits to nursing homes, after it had become clear that the virus had hit around half of Stockholm’s facilities for the elderly.

Sweden’s approach turned out to be misguided for at least three reasons. However virtuous Swedes may be, there will always be free riders in any society, and when it comes to a highly contagious disease, it doesn’t take many to cause major harm. Moreover, Swedish authorities only gradually became aware of the possibility of asymptomatic transmission, and that infected individuals are most contagious before they start showing symptoms. And, third, the composition of the Swedish population has changed.

After years of extremely high immigration from Africa and the Middle East, 25% of Sweden’s population – 2.6 million of a total population of 10.2 million – is of recent non-Swedish descent. The share is even higher in the Stockholm region. Immigrants from Somalia, Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan are highly overrepresented among COVID-19 deaths. This has been attributed partly to a lack of information in immigrants’ languages. But a more important factor seems to be the housing density in some immigrant-heavy suburbs, enhanced by closer physical proximity between generations.

It is too soon for a full reckoning of the effects of the “Swedish model.” The COVID-19 death rate is nine times higher than in Finland, nearly five times higher than in Norway, and more than twice as high as in Denmark. To some degree, the numbers might reflect Sweden’s much larger immigrant population, but the stark disparities with its Nordic neighbors are nonetheless striking. Denmark, Norway, and Finland all imposed rigid lockdown policies early on, with strong, active political leadership.

Now that COVID-19 is running rampant through nursing homes and other communities, the Swedish government has had to backpedal. Others who may be tempted by the “Swedish model” should understand that a defining feature of it is a higher death toll.