http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/2018/06/27/High-Toll-High-Deductible-Health-Care-Plans

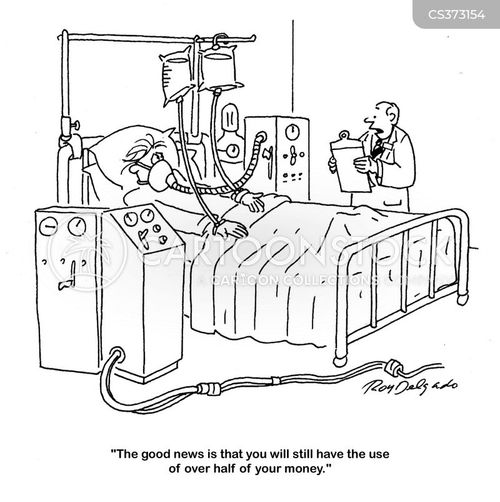

Bloomberg looks at an important trend in health care coverage: the rise of employer-based high-deductible plans that mean many patients and families simply can’t afford to get sick.

Some companies are now rethinking those policies, Bloomberg’s John Tozzi and Zachary Tracer report, after realizing that their goal of reducing costs by getting patients to have more “skin in the game” instead led workers to delay or forgo care, including medications. Patients didn’t become “better” health-care consumers. They simply cut back on what they thought they couldn’t afford — potentially driving up costs in the long run.

“High-deductible plans do reduce health-care costs, but they don’t seem to be doing it in smart ways,” said Neeraj Sood, director of research at the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California.

The trend: Nearly 40 percent of large employers offer only high-deductible plans, up from 7 percent in 2009, according to a survey by the National Business Group on Health cited by Bloomberg. And half of all covered workers now have a deductible of at least $1,000 for an individual, up from 34 percent in 2012 and 22 percent in 2009, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Nearly one in four covered workers has a deductible of $2,000 or more.

The key quote: “Why did we design a health plan that has the ability to deliver a $1,000 surprise to employees?” Shawn Leavitt, a senior human resources executive at Comcast, said at a recent conference, according to Bloomberg. “That’s kind of stupid.”

Why it matters: As employers move away from simply shifting more and more costs to their workers, Axios’ Sam Baker notes, they’re also paying more attention to bringing down underlying health care prices .

This report is the first in a series on health reform in the 2020 election campaign. Future papers will delve into key reform design questions that candidates will face, focusing on such topics as: ways to maximize health care affordability and value; how to structure health plan choices for individuals in ways that improve system outcomes; and how the experience of other nations’ health systems can inform state block-grant and public-plan proposals.

During the 2020 presidential campaign, which begins in earnest at the end of 2018, we are sure to hear competing visions for the U.S. health system. Since 1988, health care has been among the most important issues in presidential elections.1 This is due, in part, to the size of the health system. In 2018, federal health spending comprises a larger share of the economy (5.3%) than Social Security payments (4.9%) or the defense budget (3.1%).2 Moreover, for the past decade, partisan disagreement over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has dominated the health policy debate. If health care plays a significant role in the 2018 midterm elections, as some early polls suggest it will,3 the topic is more likely to play a central role in the 2020 election.

This report on health reform plans focuses on policies related to health insurance coverage, private insurance regulation, Medicare and Medicaid, supply, and tax policy. It explains why campaign plans are relevant, their history since 1940, the landscape for the 2020 election, and probable Republican and Democratic reform plans. The Republican campaign platform is likely to feature policies like those in the Graham-Cassidy-Heller-Johnson amendment: a state block grant with few insurance rules, replacing the ACA’s coverage expansion. The Democratic platform will probably defend, improve, and supplement the ACA with some type of public (Medicare-like) health plan. The exact contours and details of these plans have yet to be set.

Campaign promises, contrary to conventional wisdom, matter.4 During elections, they tell voters each party’s direction on major topics (e.g., health coverage as a choice or a right in 1992). In some cases, candidates or party platforms include detailed policies (reinsurance in Republicans’ 1956 platform, prospective payment in Democrats’ 1976 platform). Campaign plans tend to be used to solidify party unity, especially in the wake of divisive primaries (2016, e.g.).5 Election outcomes are affected by such factors as the state of the economy, incumbency, and political competition rather than specific issues.6 That said, some exit polls suggest that candidates’ views on health policy can affect election outcomes.7

Campaign plans also help set the agenda for a president, especially in the year after an election. Lyndon B. Johnson told his health advisers, “Every day while I’m in office, I’m gonna lose votes. . . . We need . . . [Medicare] fast.”8 Legislation supported by his administration was introduced before his inauguration and signed into law 191 days after it (Exhibit 1). Bill Clinton, having learned from his failure to advance health reform in his first term, signed the bill that created the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) 197 days after his second inauguration. Barack Obama sought to sign health reform into law in the first year of his first term, but the effort spilled into his second year; he signed the ACA into law on his 427th day in office. These presidents, along with Harry Truman, initiated their attempts at health reform shortly after taking office.

In addition, campaign plans are used by supporters and the press to hold presidents accountable. For instance, candidate Obama’s promises were the yardstick against which his first 100 days,9 first year,10 reelection prospects,11 and presidency were measured.12 Though only 4 percent of likely voters believe that most politicians keep their promises, analyses suggest that roughly two-thirds of campaign promises were kept by presidents from 1968 through the Obama years.13

The United States has had public health policies since the country’s founding, with its policy on health coverage, quality, and affordability emerging in the twentieth century. Teddy Roosevelt supported national health insurance as part of his 1912 Bull Moose Party presidential bid.14 Franklin Delano Roosevelt included “the right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health” in his 1944 State of the Union address, although it was not mentioned in the 1944 Democratic platform.15 Harry Truman is generally credited with being the first president to embrace comprehensive reform. He proposed national health insurance in 1945, seven months after F.D.R.’s death, and campaigned on it in 1948 as part of a program that would become known as the Fair Deal, even though it was not a plank in the Democratic platform. Legislation was blocked, however, primarily by the American Medical Association (AMA), which claimed that government sponsoring or supporting expanded health coverage would create “socialized medicine.”16 Health policy became a regular part of presidential candidates’ party platforms beginning about this time (Exhibit 2).

After Truman’s failure, the next set of presidential candidates supported expanding capacity (e.g., workforce training, construction of hospitals and clinics) and making targeted coverage improvements. In 1960, John F. Kennedy campaigned on a version of Medicare legislation: extending Social Security to include hospital coverage for seniors. It was opposed by the AMA as well, whose spokesman, the actor Ronald Reagan, claimed socialized medicine would eventually limit freedom and democracy.17 It took the death of Kennedy, the landslide Democratic victory in 1964, and persistence by Lyndon B. Johnson to enact Medicare and Medicaid, in 1965. This was about 20 years after Truman introduced his proposal; President Johnson issued the first Medicare card to former President Truman.

Shortly after implementation of Medicare and Medicaid, how best to address rising health care costs became a staple subject in presidential campaigns. Between 1960 and 1990, the share of the economy (gross domestic product) spent on health care rose by about 30 percent each decade, with the public share of spending growing as well (Exhibit 3). In his 1968 campaign, Richard Nixon raised concerns about medical inflation, and subsequently proposed his own health reform, which included, among other policies, a requirement for employers to offer coverage (i.e., an employer mandate).18 Nixon’s proposal was eclipsed by Watergate, as Jimmy Carter’s health reform promises were tabled by economic concerns. Presidents and candidates in the 1980s set their sights on incremental health reforms.19

In 1991, comprehensive health reform helped Harris Wofford unexpectedly win a Pennsylvania Senate race. In 1992, it ranked as the second most important issue to voters.20 Democratic candidates vied over health reform in the 1992 primaries, with Bill Clinton embracing an employer “pay or play” mandate. George H. W. Bush developed his own plan, which included premium tax credits and health insurance reforms. Five days after his inauguration, President Clinton tasked the first lady, Hillary Clinton, with helping to develop health care legislation in the first 100 days. Yet, mostly because he prioritized economic and trade policy, Clinton did not address a joint session of Congress until September and did not send his bill to Congress until November of 1993. Key stakeholders (including the AMA and the Health Insurance Association of America) initially supported but ultimately opposed the legislation. In September 1994, the Senate Democratic leadership declared it could not pass a bill.21 Less than two months later, Democrats lost their majorities in the House and the Senate, and did not regain them for over a decade. This created a view that comprehensive reform of the complex health system was politically impossible.22 Indeed, presidential candidates in 1996, 2000, and 2004 did not emphasize major health policies. That said, by 2004, health system problems had escalated and, at least on paper, the candidates’ plans addressing them had expanded.23

In 2008, health reform was a dominant issue in the Democratic primaries and platform. Hillary Clinton supported a requirement for people who could afford it to have coverage (i.e., the individual mandate). Barack Obama limited his support to a requirement that all children be insured. Both candidates supported an employer mandate.24 John McCain countered with a plan whose scope exceeded those of many Republican predecessors: it would cap the tax break for employer health benefits and use the savings to fund premium tax credits for the individual market.25 Attention to health reform waned during the general election, as the economy faltered. Even so, the stage was set for a legislative battle. President Obama opened the door to his rivals’ ideas at a White House summit in March 2009.26 After more than a year of effort, he signed the Affordable Care Act into law.27 Obama said that he did so “for all the leaders who took up this cause through the generations — from Teddy Roosevelt to Franklin Roosevelt, from Harry Truman, to Lyndon Johnson, from Bill and Hillary Clinton, to one of the deans who’s been fighting this so long, John Dingell, to Senator Ted Kennedy.”28

Nonetheless, the partisan fight over the ACA extended into the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections. Despite the ACA’s resemblance to his own 2006 reform plan for Massachusetts, Mitt Romney, as the 2012 Republican presidential candidate, vowed to repeal the ACA before its major provisions were implemented; Republicans would subsequently replace it with conservative ideas (mostly to be developed). Four years later, even though the health system landscape had dramatically changed following the ACA’s implementation, the Republicans’ position had not altered.29 Candidate Donald Trump joined his primary rivals in pledging to “repeal and replace Obamacare” (he also embraced unorthodox ideas such as Medicare negotiation for drug prices). Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton proposed a wide array of improvements to the ACA rather than a wholesale replacement of it with a “Medicare for All” single-payer proposal, as did her Democratic primary rival, Bernie Sanders.30 The intra-party differences among primary candidates in 2016 increased attention to the party platforms relative to previous elections.31 But despite continued voter interest (Exhibit 4), differences in health policy were not credited with determining the outcome of the 2016 election.

President Trump’s attempt to fulfill his campaign promise to repeal and replace the ACA dominated the 2017 congressional agenda. In January 2017, the Republican Congress authorized special voting rules toward this effort, while President Obama was still in office. On the day of his inauguration, Trump signed an executive order to reduce the burden of the law as his administration sought its prompt repeal.32 Yet among other factors,33 the lack of a hammered-out, vetted, and agreed-upon replacement plan crippled the Republicans’ progress.34 Speaker Paul Ryan had to take his bill off the House floor on March 24, 2017, because it lacked the necessary votes; the House passed a modified bill on May 4. Senator Mitch McConnell’s multiple attempts in June and July to secure a majority in favor of his version of a health care bill failed on July 26, when Senator John McCain cast the deciding vote against it. In September, Senators Lindsey Graham, Bill Cassidy, Dean Heller, and Ron Johnson failed to get 50 cosponsors for their amendment, the prerequisite for its being brought to the Senate floor.35 The Republicans subsequently turned to tax legislation and, in it, zeroed out the tax assessment associated with the ACA’s individual mandate. At the bill’s signing on December 22, Trump claimed that “Obamacare has been repealed,”36 despite evidence to the contrary.37

A different type of legislative effort began in mid-2017: bipartisan attempts to improve the short-run stability of the ACA’s individual market. This was in part necessitated by the Trump administration’s actions pursuant to the Inauguration Day executive order: reductions in education efforts, marketing funding, and premium tax credits, among others.38 On October 12, 2017, the president signed a second ACA executive order, directing agencies to authorize the sale of health plans subject to fewer regulatory requirements.39 On the same day, his administration halted federal funding for cost-sharing reductions, a form of subsidy, claiming the ACA lacked an appropriation to make such payments. Concerns that these actions would increase premiums, reduce insurer participation, and discourage enrollment prompted coalitions of bipartisan lawmakers to introduce bills. Most notable was a bill by Senators Lamar Alexander and Patty Murray; their proposal, released October 18, 2017, had 12 Republican cosponsors and implicit support from all Democrats, giving it the 60 votes needed in the Senate to overcome a filibuster.40 Yet the version that Senator McConnell ultimately brought to the floor for a vote, in March 2018, included changes that repelled Democrats, preventing its passage.41 Partisans on both sides have blamed this failure, in part, for emerging increases in health insurance premiums.

Indeed, benchmark premiums in the health insurance marketplaces rose by an average of over 30 percent in 2018 and are projected to increase by 15 percent in 2019, largely because of policy changes.42 Some data suggest that the growth in health care costs may be accelerating as well.43 This may have contributed to an increase in the number of uninsured Americans. One survey found that the number of uninsured adults, after falling to a record low in 2016, had risen by about 4 million by early 2018.44 These statistics could heighten candidates’ interest in health policy in 2020.

Public opinion, too, could help health reform gain traction. Tracking polls suggest that concerns about health care persist, with 55 percent of Americans worrying a great deal about the availability and affordability of health care, according to a poll from March 2018.45 Interestingly, while the partisan differences of opinion on the ACA continue, overall support for the ACA has risen, reaching a record high in February 2018 (Exhibit 5).

This concern about health care has entered the 2018 midterm election debate. It is currently a top midterm issue among registered voters, a close second to jobs and the economy.46 Some House Republicans who formerly highlighted their promise to repeal and replace the ACA no longer do so in light of the failed effort of 2017.47 Democrats, in contrast to previous elections, have embraced the ACA, unifying around its defense in the face of Republican “sabotage.”48 The debate also has been rekindled by Trump’s decision to abandon legal defense of key parts of the ACA.49 Regardless of what happens in the courts, this signifies his antipathy toward the law. Barring a midterm surprise, the next Congress is unlikely to succeed where the last one failed. As such, “repeal and replace” would be a repeat promise in Trump’s reelection campaign.

Against this backdrop, presidential primary candidates and the political parties will forge their health care promises, plans, and platforms. Common threads from past elections are likely to be woven into the 2020 debate. The different parties’ views of the balance between markets and government have long defined their health reform proposals.50 Republicans will most likely still be against the ACA as well as uncapped Medicare and Medicaid spending, and for market- and consumer-driven solutions. Democrats will most likely blame Republicans’ deregulation for rising health care costs; defend the ACA, Medicare, and Medicaid; and advocate for a greater role for government in delivering health coverage and setting payment policy. Potential policies for inclusion in candidates’ plans have been introduced in Congress (Exhibit 6). But major questions remain, such as: how will these campaign plans structure choices for individuals and employers, promote efficient and high-quality care, and learn from the experience of local, state, national, and international systems?

President Trump has indicated he will run for reelection in 2020.51 His fiscal year 2019 budget included a proposal “modeled closely after the Graham-Cassidy-Heller-Johnson (GCHJ) bill.” It would repeal federal financing for the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and health insurance marketplaces, using most of the savings for a state block grant for health care services. It would also impose a federal per-enrollee spending cap on the traditional Medicaid program. States could waive the ACA’s insurance reforms.52 The congressional bill also would repeal the employer shared responsibility provision (i.e., the employer mandate) and significantly expand tax breaks for health savings accounts, among other policies.53 The framework for this proposal — repealing parts of the ACA, replacing them with state block grants, reducing regulation, and expanding tax breaks — is similar to the 2016 Republican platform.

Trump may continue to express interest in lowering prescription drug costs. In 2016 and early 2017, he supported letting Medicare negotiate drug prices54 — a policy excluded from the 2016 Republican platform and his proposals as president. His 2019 budget seeks legislation primarily targeting insurers and other intermediaries that often keep a share of negotiated discounts for themselves.55 On May 11, 2018, he released a “blueprint” to tackle drug costs, including additional executive actions and ideas for consideration. Polls suggest that prescription drug costs rank high among health care concerns.56

One policy initiative in the recent Republican platforms but not embraced by the president is Medicare reform. The idea of converting Medicare’s defined benefit into a defined contribution program and raising the eligibility age to 67 was supported by Vice President Mike Pence when he was a member of Congress and by Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.57 Major Medicare changes were excluded from the 2017 ACA repeal and replace proposals. In contrast, versions of Medicaid block grant proposals appeared in various bills, including the GCHJ amendment, as well as numerous Republican presidential platforms.

Historically, presidents running for reelection have limited competition in primaries. Those challengers, by definition, emphasize their differences with the incumbent, which may include policy. It may be that John Kasich will run on maintaining the ACA Medicaid expansion but otherwise reforming the program (his position as governor of Ohio throughout 2017). Or, Rand Paul could campaign on his plan to repeal even more of the ACA than the Republicans’ 2017 bills attempted to do. Incumbents tend to have slimmer campaign platforms than their opponents in general and primary elections, since their budget proposals, other legislative proposals, and executive actions fill the policy space (see Reagan, Clinton, George W. Bush, Obama). Exceptions include George H. W. Bush, who in 1992 developed a plan given voters’ concerns about health; and Nixon, who offered a proposal for health reform at the end of his first term.

It is possible and maybe probable that the ultimate Democratic Party platform in 2020 will resemble that of 2016: build on the ACA and include some sort of public plan option. Legislation has been introduced during this congressional session that builds on the law by extending premium tax credits to higher-income marketplace enrollees (e.g., Feinstein, S. 1307), lowering deductibles and copayments for middle-income marketplace enrollees (e.g., Shaheen, S. 1462), providing marketplace insurers with reinsurance (e.g., Carper, S. 1354), and strengthening regulation of private market insurance (e.g., Warren, S. 2582). Some proposals aim to increase enrollment following the effective repeal of the individual mandate, by, for example, raising federal funding for education and outreach, and testing automatic enrollment of potentially eligible uninsured people (e.g., Pallone, H.R. 5155). These proposals would have different effects on health insurance coverage, premiums, and federal budget costs.58

The Democrats will inevitably discuss a public plan in their platform, although the primary contenders will most likely disagree on its scale (e.g., eligibility) and design (e.g., payment rates, benefits).59 In September 2017, Senator Bernie Sanders introduced the Medicare for All Act (S. 1804). It would largely replace private insurance and Medicaid with a Medicare-like program with generous benefits and taxpayer financing. “Medicare for more” proposals have also been introduced: Medicare Part E (Merkley, S. 2708), an option for individuals and small and large businesses; Medicare X (Bennet, S. 1970), which is available starting in areas with little insurance competition or provider shortages; and a Medicare buy-in option, for people ages 50 to 65 (Higgins, H.R. 3748). A Medicaid option (Schatz, S. 2001), similar to Medicare Part E, offers a public plan choice to all privately insured people, aiming to capitalize on the recent popularity of that program. Publicly sponsored insurance plans have long been included in Democratic presidents’ platforms, although the government’s role has ranged from regulating the private plans (Carter, Clinton) to sponsoring them (Truman, Obama). It may be that the candidate who prevails in the primaries will determine whether the Democratic platform becomes “Medicare for all” or “Medicare for more.”

This may be the extent of Medicare policies in the 2020 Democratic platform. Relatively high satisfaction and low cost growth in Medicare have limited Democratic interest in Medicare policy changes in recent years. Similarly, Democrats have not introduced or embraced major reforms of Medicaid. However, the public concern about prescription drug costs has fueled Democratic as well as Republican proposals, some of which target the drug companies (e.g., addressing “predatory pricing,” allowing Medicare rather than prescription drug plans to negotiate the prices for the highest-cost drugs).60

Predictions about presidential campaigns have inherent limits, as many experts learned in the 2016 election. Events concerning national security (e.g., conflict), domestic policy (e.g., a recession), or the health system (e.g., a disease outbreak) could alter the policy choices of presidential candidates. New ideas could emerge, or candidates could take unconventional approaches to improving the health system. And, while campaign plans have relevance, the long history of attempts at health reform underscores that by no means are promises preordained.

That said, perennial policies and recent political party differences will likely figure in 2020. Republican presidential candidates, with few exceptions, have adopted a small government approach to health reform: shifting control to states, cutting regulation, preferring tax breaks and block grants over mandatory federal funding, and trusting markets to improve access, affordability, and quality. Democratic presidential candidates have supported a greater government role in the health system, arguing that market solutions are insufficient, and have defended existing programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and, now, the ACA. Some will probably support the government’s taking a primary role in providing coverage given criticism of the efficacy and efficiency of private health insurers. The direction and details of the campaign plans for 2020 will be developed in the coming months and year. Given such plans’ potential to shape the next president’s agenda, now is the time to scrutinize, modify, and generate proposals for health reform.

President Trump is expected to soon address the nation about the rising cost of prescription drugs. But Americans are worried about more than drug prices. New findings from the Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey show that consumers’ confidence in their ability to afford all their needed health care continues to decline.

Last week, we reported that the survey indicated a small but significant increase in the uninsured rate among working-age adults since 2016. In this post, we look at people’s views of the affordability of their health care. The Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey is a nationally representative telephone survey conducted by SSRS that tracks coverage rates among 19-to-64-year-olds, and has focused in particular on the experiences of adults who have gained coverage through the marketplaces and Medicaid. The latest wave of the survey was conducted between February and March 2018.1

In each wave of the survey, we’ve asked respondents whether they have confidence in their ability to afford health care if they were to become seriously ill. In 2018, 62.4 percent of adults said they were very or somewhat confident they could afford their health care, down from a high of nearly 70 percent in 2015 (Table 1). Only about half of people with incomes less than 250 percent of poverty ($30,150 for an individual) were confident they could afford care if they were to become very sick, down from 60 percent in 2015 and about 20 percentage points lower than the rate for adults with higher incomes. There were also significant declines in confidence among young adults, those ages 50 to 64, women, and people with health problems. Declines were significant among both Democrats and Republicans.

We asked people with health insurance how confident they were that their current insurance will help them afford the health care they need this year. Majorities of adults were somewhat or very confident in their coverage; those with employer coverage were the most confident. More than half (55%) of adults insured through an employer were very confident their coverage would help them afford their care compared to 31 percent of adults with individual market coverage and 41 percent of people with Medicaid (Table 2). The least confident were adults enrolled in Medicare. Working-age adults enrolled in Medicare were the sickest among insured adults and the second-poorest after those covered by Medicaid (data not shown).2

We asked people whether, over the past year, their health care, including prescription drugs, had become harder for them to afford, easier to afford, or if there had been no change. The majority (66%) said there had been no change, one-quarter (24%) said it had become harder to afford, and 8 percent said it had become easier (Table 3). People with individual market coverage were significantly more likely than those with employer coverage or Medicaid to say health care had become harder to afford. About one-third of adults with deductibles of $1,000 or more said health care had become harder to afford, twice the share of those who had no deductible. About one-third of those enrolled in Medicare and 41 percent who were uninsured also reported that their health care had become harder to afford.

Accidents and other medical emergencies can leave both uninsured and insured people with unexpected medical bills, which usually require prompt payment. We asked people if they would have the money to pay a $1,000 medical bill within 30 days in the case of an unexpected medical event. Nearly half (46%) said they would not have the money to cover such a bill in that time frame (Table 4). Women, people of color, people who are uninsured, those covered by Medicaid or Medicare, and those with incomes under 250 percent of poverty were among the most likely to say they couldn’t pay the bill.

Fourteen percent of adults said that health care was their biggest personal financial concern, after mortgage or rent (23%), student loans (17%), and retirement (17%) (Table 5). Those most likely to cite health care as their greatest financial concern were people who could potentially face high out-of-pocket costs because they were uninsured or had high-deductible health plans.

Uninsured adults are the least confident in their ability to pay medical bills. But the risk of high out-of-pocket health care costs doesn’t end when someone enrolls in a health plan. The proliferation and growth of high-deductible health plans in both the individual and employer insurance markets is leaving people with unaffordable health care costs. Many adults enrolled in Medicare for reasons of disability or serious illness also report unease about their health care costs. An estimated 41 million insured adults have such high out-of-pocket costs and deductibles relative to their incomes that they are effectively underinsured. As this survey indicates, the nation’s health care cost burden is felt disproportionately by people with low and moderate incomes, people of color, and women.

The ACA’s reforms to the individual insurance market have doubled the number of people who now get insurance on that market to an estimated 17 million, with approximately half receiving subsidies through the ACA marketplaces. The ACA also has made it possible for people who were regularly denied coverage by insurers — older Americans and those with health problems — to get insurance. They are now entitled by law to an offer should they want to buy a plan.

But as this survey suggests, the ACA’s reforms did not fully resolve the individual market’s relatively higher costs for all those enrolled, compared to employer coverage or Medicaid. Moreover, recent actions by Congress and the Trump administration, including the repeal of the individual mandate penalty and loosened restrictions on plans that don’t comply with the ACA, are expected to exacerbate those costs for many. In the survey, people with individual market coverage are more likely than those with employer coverage or Medicaid to say that their health care, including prescription drugs, has become harder to afford in the past year. They express less confidence than those with employer coverage that their insurance will help them afford their care this year. As explained in the first post, there are a number of policy options that Congress can pursue that would improve individual market insurance’s affordability and cost protection. In the absence of bipartisan Congressional agreement on legislation, several states are currently pursuing their own solutions. But if current trends continue, the federal government will likely confront growing pressure to provide a national solution to America’s incipient health care affordability crisis.

Gubernatorial Hopefuls Look To Health Care For Election Edge

California’s leading gubernatorial candidates agree that health care should work better for Golden State residents: Insurance should be more affordable, costs are unreasonably high, and robust competition among hospitals, doctors and other providers could help lower prices, they told California Healthline.

What they don’t agree on is how to achieve those goals — not even the Democrats who represent the state’s dominant party.

“Health care gives them the perfect chance to crystalize that divide” between the left-wing progressives and the “moderate pragmatists” of the Democratic Party, said Thad Kousser, a political science professor at the University of California-San Diego.

Consider the top two Democratic candidates, who both aim to cover everyone in the state, including immigrants living here without authorization.

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom — billed as a liberal Democrat — supports a single-payer health care system. That means gutting the health insurance industry to create one taxpayer-funded health care program for everyone in the state.

But former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa has called single-payer “unrealistic.” He advocates achieving universal health coverage through incremental changes to the current system.

Under California’s “top-two” primary system, candidates for state or congressional office will appear on the same June 5 ballot, regardless of party affiliation. The top two vote-getters advance to the November general election.

A poll in late April by the University of California-Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies puts Newsom in first place with the support of 30 percent of likely voters, followed by Republicans John Cox, with 18 percent, and Travis Allen with 16 percent. Trailing behind were Democrats Villaraigosa, with 9 percent, John Chiang with 7 percent and Delaine Eastin with 4 percent. Thirteen percent of likely voters remained undecided.

Health care is in the forefront of this year’s gubernatorial campaign because of recent federal attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which would have threatened the coverage of millions of Californians, said Kim Nalder, professor of political science at California State University-Sacramento. California has pushed back hard against Republican efforts in Congress to dismantle the law.

“There’s more energy in California around the idea of universal coverage than you see in lots of other parts of the country,” Nalder said. Democrats and those who indicate no party preference make up almost 70 percent of registered voters. Those voters care more about health coverage than Republicans, she said.

“Whoever is most supportive [of universal health care] is likely to win the votes,” she said.

The top Republican candidates, Cox and Allen, are not fans of increased government involvement, however. They favor more market competition and less regulation to lower costs, expand choice and improve quality.

“Governments make everything more expensive,” said Cox, a former adviser to former House Speaker Newt Gingrich during his presidential run. “The private sector looks for efficiencies.”

California Healthline reached out to the top six candidates based on the institute’s poll, asking about their positions on health insurance, drug prices, the opioid epidemic and hospital consolidation.

As health care costs keep rising, more people seem to be skipping physician visits.

It’s not fear of doctors, however, but more of a phobia about the bills that could follow. Higher deductibles and out-of-network fees are just some of the out-of-pocket costs that can hit a consumer’s pockets.

U.S. health care costs keep rising, and hit more than $10,000 a year per person in 2016. According to a recent national poll, over the past 12 months, 44 percent of Americans said they didn’t go to the doctor when they were sick or injured because of financial concerns. Meanwhile, 40 percent said they skipped a recommended medical test or treatment.

Also, the study found most people who are delaying or skipping care actually have health insurance. Some 86 percent of those surveyed said they’re covered either through their employer, have insurance they purchased directly, or through government programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

“There have been so many changes in the health care landscape in the United States that this news is not entirely surprising,” Cleveland Clinic president and CEO Tom Mihaljevic told CNBC’s “On the Money” in a recent interview. However, Mihaljevic warned that skipping visits or treatment can be counterproductive.

“One of most important consequences of skipping medical care or delaying care ultimately impacts the quality of care, impacts the outcome,” he said. “Untimely visits or delay of visits to the physician ultimately leads to the increased cost of care.”

However, the poll, conducted by the University of Chicago and the West Health Institute, found Americans fear large medical bills more than they do serious illness. The data showed 33 percent of those surveyed were “extremely afraid” or “very afraid” of getting seriously ill. About 40 percent said paying for health care is more frightening than the illness itself.

“Part of problem here is healthcare tends to be very complex, and every patient typically requires a number of procedures and tests to be done, so it’s really difficult to estimate the upfront cost of care, ” Mihaljevic told CNBC.

Additionally, the survey found 54 percent of those polled received one or more medical bills over the past year for something they thought was covered by their insurance. And 53 percent received a bill that was higher than they expected.

Mihaljevic acknowledged the range of different fees for the same services should be made clearer for consumers. “There is an absolute need for increased transparency when it comes to cost and this is one of mandates for our industry as a whole,” he said.

To combat rising health costs, Mihaljevic explained that the Cleveland Clinic is focused on the “standardization of care.”

“When we reduce the variability of the way we take care of patients, we manage to decrease the cost and at the same time improve the quality of care that we provide,” he added.

In addition, the health system is also pushing ahead with advances in medical technology, which may help bring down costs in the future. “We firmly believe digital technology is going to have a transformative effect,” Mihaljevic said. Among the initiatives is a partnership with IBM Watson to use big data to help clinical decision making.

And through the Cleveland Clinic’s Express Care Online, 25,000 virtual doctor visits were completed in 2017. Although virtual visits are billed as more cost effective,new data suggest otherwise.

“We are constantly looking how to make our care more accessible more affordable and of higher quality,” Mihaljevic added.

Because of the high cost of healthcare, 44% Americans didn’t go see a physician last year when they were sick or injured, according to a new survey.

The West Health Institute/NORC at the University of Chicago national poll comes as policymakers and health insurance companies are predicting a jump in health premiums and out-of-pocket costs, particularly for Americans with individual coverage under the Affordable Care Act. The $1.3 trillion spending bill signed into law last week by President Donald Trump didn’t include reinsurance programs and money to restore Obamacare funds to help Americans pay co-payments and deductibles despite bipartisan support in the Senate.

Cost continues to be a barrier to treatment with 40% of Americans who say they “skipped a recommended medical test or treatment in the last 12 months due to cost.” Another 32% were “unable to fill a prescription or took less of a medication because of the cost,” the West Health/NORC poll of more than 1,300 adults said.

“The high cost of healthcare has become a public health crisis that cuts across all ages as more Americans are delaying or going without recommended medical tests and treatments,” West Health Institute chief medical officer Dr. Zia Agha said in a statement accompanying the poll results. The survey is being released at this week’s American Society on Aging 2018 Aging in America Conference in San Francisco.

The West Health-NORC poll is the latest national survey showing Americans continued frustration with high healthcare costs even as the U.S. spends more than $3.3 trillion annually on healthcare.

Several recent polls have indicated healthcare is back on the top of voters’ concerns as they head to the polls this November for mid-term Congressional and statewide general elections. A Kaiser Health Tracking poll published earlier this month ranked “health care costs as the top health care issue mentioned by voters when asked what they want to hear 2018 candidates discuss.”

https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180212.852840/full/

During his first year in office, President Donald Trump spoke often about the problem of high drug prices but took no action on the subject. President Trump’s new budget proposal and a newly released white paper from the White House Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) aim to change that by laying out a strategy for action moving forward. These documents are, of course, aspirational, but they do provide a window into the administration’s priorities, and they should be evaluated to consider whether the administration has a possibility of achieving its stated goals.

In this post, I review several of the key elements of those proposals, considering their impact on a range of relevant dimensions. I discuss what’s included in the proposals, and, as importantly, what’s left out.

The bulk of the proposed reforms would act on the Medicare and Medicaid programs. For Medicare, the Trump administration’s proposals are largely targeted at 1) assisting beneficiaries with high out-of-pocket costs and 2) realigning incentives to alter prescribing and reimbursement practices.

First, the administration is advancing a set of proposals to assist Medicare Part D beneficiaries with high out-of-pocket costs. Both the white paper and budget proposal argue that plans should be required to share with beneficiaries at the point-of-sale some amount of the rebates the plan negotiates with drug manufacturers. In November, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) already requested public comments on the implementation of this proposal, and it seems as if the budget document’s inclusion of the proposal is evidence that the administration is hoping to move it forward.

However, like many of the other reforms in the budget proposal and white paper, there are few details proposed. In CMS’s November proposal, the agency modeled a set of scenarios in which insurers pass through 33 percent, 66 percent, 90 percent, or 100 percent of their negotiated rebates. Each scenario comes with a set of advantages for beneficiaries, but also costs for the federal government. That is, CMS anticipated that reducing cost-sharing for particular high-cost beneficiaries would increase premiums for all beneficiaries, and therefore increase CMS’ overall spending through premium subsidies. How much the proposal would increase overall spending depends on the amount of rebates being passed through.

The budget proposal simply says that sponsors must pass through “at least one-third” of total rebates, so it does not provide further clarity on this proposal. However, it states that this proposal will cost the government $42.2 billion over 10 years. That estimate lies between CMS’s November estimates for 33 percent ($27.3 billion in spending) and 66 percent ($55.1 billion in spending), so it is possible that the administration has in mind a pass-through provision at 50 percent or so.

Another proposal aimed at out-of-pocket costs would establish an out-of-pocket maximum for patients who enter the Medicare Part D catastrophic phase. Currently, patients who reach the catastrophic phase of the Part D benefit are responsible for 5 percent of the costs of their prescription drugs, with no upper limit. The budget proposal would reduce their payments to 0 percent, although it is light on the details as to how this would be accomplished. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that just over one million Part D enrollees have out-of-pocket costs above this threshold, and those patients would likely be the primary beneficiaries of this proposal. At the same time, however, the budget proposes to exclude manufacturer discounts from patient out-of-pocket cost calculations, which would likely slow the rate at which patients move into the catastrophic phase.

Second, the Trump administration proposes a number of changes to drug classification and reimbursement that would both enable plan sponsors to negotiate more effectively and alter prescribing behavior. The budget proposal would change current Part D plan formulary rules, requiring sponsors to cover just one drug per class, rather than two. The proposal also mentions increased use of utilization management tools for the six protected classes of drugs, suggesting that the general coverage requirement for those classes would remain as-is. This proposal is projected to save $5.5 billion over ten years.

More interestingly, both the budget proposal and CEA white paper suggest the possibility of moving a set of Part B drugs (those administered in an outpatient setting) into Part D coverage. Medicare Part B does not presently have a number of the tools that enable Part D plan sponsors to negotiate discounts with drug manufacturers, and Secretary Alex Azar spoke during his confirmation hearing about the need to “take the learnings from Part D and apply them to Part B.” This proposal would accomplish that goal, just through the reverse mechanism: by shifting drugs from Part B into Part D. The budget proposal envisions giving the authority to do this to the Secretary, noting that “[t]he Secretary will exercise this authority when there are savings to be gained from price competition.” As such, it does not provide any particular budgetary impact.

The budget proposes two other changes to Part B reimbursement. At present, when a physician is reimbursed for providing a drug under Part B, she is reimbursed based on the Average Sales Price (ASP) of the drug plus 6 percent. There is widespread concern that this reimbursement system encourages physicians to prescribe and administer more expensive drugs than may be medically necessary. The Obama administration proposed a demonstration project that would have moved from the current ASP+6 percent system to a system of ASP+2.5 percent+a flat fee for prescribing the product. After extensive criticism from a range of stakeholders, the administration shelved the initiative. Now, the administration is proposing to reduce payment rates for new drugs (for which the ASP information is not yet available, and so for which the only price available is the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC)). Instead of paying 106 percent for these new products, the administration would pay 103 percent of the WAC during the period before ASP information has yet to be provided. This proposal is quite narrow in its scope, applying only to new drugs and only during the brief period before ASP information is available; it is therefore unlikely to save much money.

The Trump administration is also proposing to establish an inflation limit for the reimbursement of Part B drugs more generally. Instead of continually updating the ASP+6 percent figure if the ASP increases, this proposal would limit the growth of the reimbursement to the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers. CMS would therefore pay “pay the lesser of (1) the actual ASP +6 percent or (2) the inflation-adjusted ASP +6 percent.” At present, Medicaid is protected from price increases when the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) for a drug increases faster than inflation. The Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General has proposed that CMS and Congress consider extending this provision to Medicare Part D, but as yet Congress has not moved to do so. This budget proposal can be thought of as proposing a similar constraint on Part B pricing.

The Medicaid portion of the budget proposal puts forth an idea which is potentially ground-breaking, but which is also potentially a sign of the administration’s recalcitrance to move on drug pricing (depending on the details). Specifically, the administration is proposing “new statutory demonstration authority to allow up to five states more flexibility in negotiating prices with manufacturers, rather than participate in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, and to make drug coverage decisions that meet state needs.” The idea is something like this: at present, state Medicaid programs must cover essentially all drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which limits their ability to extract discounts. To be sure, Medicaid programs are already entitled by statute to large discounts off of the AMP, and to the inflation clawback as noted above. But many state Medicaid programs are worried that pharmaceutical spending has become an unsustainable part of their budget and are seeking ways to control their costs in this area. This proposal might empower them to do so.

Here’s the thing: Massachusetts has already submitted an 1115 waiver to CMS along these lines. Massachusetts is seeking 1) to pay for a single drug in each therapeutic class (as noted above, this is a reform the administration is proposing to make to Medicare Part D), and 2) to exclude entirely from coverage drugs “with limited or inadequate evidence of clinical efficacy,” likely to be those approved through the FDA’s accelerated approval process. This budget proposal may be a sign that the administration is interested in approving Massachusetts’ waiver. However, the fact that the budget explicitly calls for new statutory authority to do so suggests that the administration may not think it has the legal authority to approve Massachusetts’ waiver, as is. And given Congress’ inability to act thus far on drug pricing, the administration may be seeking to hide behind Congress’ inaction here.

Yet the call for new statutory authority is puzzling. At present, pharmaceutical coverage is an optional benefit under the Medicaid program. States do not have to cover drugs and therefore are not required to participate in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, although all have chosen to do so, and choosing to do so comes with a set of requirements. But it is not clear to me why CMS could not conduct this demonstration at present, under the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s (CMMI) existing authority.

A potential clue may lie in the administration’s statement that the demonstration would “exempt prices negotiated under the demonstration from best price reporting.” Having written recently on the topic of the Medicaid best-price rule and innovative contracting for pharmaceuticals, it is not clear to me exactly why this is a sticking point. The Medicaid best price rule entitles Medicaid to the “best price” available for a particular drug for a particular set of providers. The statute contains large carve-outs—for instance, discounts provided to the Department of Veterans Affairs or to Medicare Part D are exempt from the best-price calculation. But it is strange to talk about needing to exempt Medicaid programs from the best-price rule when the best-price rule was intended to benefit Medicaid itself. I imagine that the administration sees the 340B program as a potential concern here, but again it is not obvious why CMMI could not waive the best-price rule as part of its existing authority.

As I have written here previously, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb has been at the forefront of the Trump administration’s efforts on drug pricing. He has taken a number of actions to promote generic competition, and although it will take some time to observe their benefits, the FDA’s existing legal authority to address drug pricing issues is quite narrowly circumscribed. The CEA white paper and budget proposal largely acknowledge this point, with the white paper lauding the actions the FDA has taken thus far on expediting review of generic drug applications, providing guidance on the development of complex generics, and other similar activities.

President Trump’s budget proposal calls for Congress to give the FDA more power to promote generic competition, by “ensur[ing] that first-to-file generic applicants who have been awarded a 180-day exclusivity period do not unreasonably and indefinitely block subsequent generics from entering the market beyond the exclusivity period.” More specifically, the concern is that first-to-file generic applicants—perhaps those whose initial applications may be rejected—can unduly delay generic entry while they remedy the deficiencies in their application. The administration projects that this reform will save the government $1.8 billion in Medicare savings over 10 years.

Other pieces of legislation have called for reform of the 180-day exclusivity period in different ways. Last year, Democrats in both the House and Senate introduced the Improving Access to Affordable Prescription Drugs Act, which included provisions preventing generic entrants from receiving the statutory 180-day exclusivity benefit if they had engaged in pay-for-delay conduct (Sections 402 and 403). But the idea in the president’s budget proposal may dovetail nicely with the FDA’s efforts to improve first-cycle approval rates for abbreviated new drug application products, as well.

Perhaps what’s most notable about the budget proposal and the CEA white paper is not what’s included, but rather what is missing. Gone are some of President Trump’s older arguments that Medicare should negotiate drug prices, or that drug importation should be permitted more widely. Some of the more significant cost-saving provisions from President Obama’s budget, like a reform that would have put low-income patients back on Medicaid prices, are also absent.

A key set of missing proposals are those which would directly assist privately insured patients. The budget’s focus on Medicare and Medicaid may well have a positive impact on the more than 100 million Americans enrolled in those programs. But for the roughly half of Americans (closer to 160 million) with employer-sponsored insurance, these reforms will provide no assistance. Growing numbers of Americans with employer-sponsored insurance are enrolled in high-deductible plans, and many of them may face the same affordability concerns that Medicare beneficiaries are facing.

You could imagine proposals that would address the drug pricing problem more broadly, rather than just within the publicly-insured population. The above-mentioned Improving Access to Affordable Prescription Drugs Act would have addressed the problem of drug pricing for a broader segment of the population. As I’ve explained here, the Act would have taxed companies which engage in large, year-over-year list price increases. It would also have capped patient out-of-pocket costs in Affordable Care Act-regulated plans, at $250 per month for an individual or $500 per month for a family.

More generally, even these proposals which would affect drug companies directly would have a minimal impact on their bottom lines. This set of proposals is largely very friendly to the pharmaceutical industry and is primarily aimed at curtailing patients’ financial burdens and tweaking incentives for stakeholders at the margin.

In this blog post, I have covered just a handful of the many different drug pricing-related proposals included in the new budget proposal and in the CEA white paper. As usual, observers should stay tuned to the actions CMS and the FDA take on this front, as they will show whether the administration is serious about these proposals or is merely posturing.