Cartoon – Strong Sense of Right and Wrong

I am intentionally breaking into my series on Body Language to write about my core material on trust because a new Podcast Interview has just been released that contains some vital information about trust. The interview is with Andrew Brady, CEO of the XLR8 Team and author of an upcoming book, “For the ƎVO⅃ution of Business.”

In my leadership classes, I often like to pose 3 challenging questions about the nature of trust.

As people grapple with the questions, it helps them sort out for themselves a deeper meaning of the words and how they might be applied in their own world. The three questions are:

• What is the relationship between trust and vulnerability?

• Can you trust someone you fear?

• Can you respect someone you do not trust, and can you trust someone you do not respect?

I have spent a lot of time bouncing these questions around in my head. I am not convinced that I have found the correct answers (or even that correct answers exist). I have had to clarify in my own mind the exact meanings of the words trust, vulnerability, fear, and respect.

Before you read this article further, stop here and ponder the three questions for yourself. See if you can come to some answers that might be operational for you.

Thinking about these concepts, makes them become more powerful for us. I urge you to pose the three questions (without giving your own answers) to people in your work group. Then have a quality discussion about the possible answers. You will find it is a refreshing and deep conversation to have.

Here are my answers (subject to change in the future as I grow in understanding):

1. What is the relationship between trust and vulnerability?

Trust implies vulnerability. When you trust another person, there is always a chance that the person will disappoint you. Ironically, it is the extension of your trust that drives a reciprocal enhancement of the other person’s trust in you. If you are a leader and you want people in your organization to trust you more, one way to achieve that is to show more trust in them.

That is a very challenging concept for many managers and leaders. They sincerely want to gain more trust, but find it hard to extend higher trust to others. As Abraham Lincoln once said, “It is better to trust and be disappointed every once in a while than to not trust and be miserable all the time.”

2. Can you trust someone you fear?

Fear and trust are nearly opposites. I believe trust cannot kindle in an organization when there is fear, so one way to gain more trust is to create an environment with less fear. In the vast majority of cases, trust and lack of fear go together.

The question I posed is whether trust and fear can ever exist at the same time. I think it is possible to trust someone you fear. That thought is derived from how I define trust.

My favorite definition is that if I trust you, I believe you will always do what you believe is in my best interest – even if I don’t appreciate it at the time. Based on that logic, I can trust someone even if I am afraid of what she might do as long as I believe she is acting in my best interest.

For example, I may be afraid of my boss because I believe she is going to give me a demotion and suggest I get some training on how to get along with people better. I am afraid of her because of the action she will take, while on some level I am trusting her to do what she believes is right for me.

Let’s look at another example. Suppose your supervisor is a bully who yells at people when they do not do things to his standards. You do not appreciate the abuse and are fearful every time you interact with him. You do trust him because he has kept the company afloat during some difficult times and has never missed a payroll, but you do not like his tactics.

3. Can you respect someone you do not trust & can you trust someone you do not respect?

This one gets pretty complicated. In most situations trust and respect go hand in hand. That is easy to explain and understand. But is it possible to conjure up a situation where you can respect someone you do not yet trust? Sure, we do this all the time.

We respect people for the things they have achieved or the position they have reached. We respect many people we have not even met. For example, I respect Nelson Mandela, but I have no basis yet to trust him, even though I have a predisposition to trust him based on his reputation.

Another example is a new boss. I respect her for the position and the ability to hold a job that has the power to offer me employment. I probably do not trust her immediately. I will wait to see if my respect forms the foundation on which trust grows based on her actions over time.

If someone has let me down in the past, and I have lost respect for that person, then there is no basis for trust at all. This goes to the second part of the question: Can you trust someone you do not respect?

I find it difficult to think of a single example where I can trust someone that I do not respect. That is because respect is the basis on which trust is built. If I do not respect an individual, I believe it is impossible for me to trust her. Therefore, respect becomes an enabler of trust, and trust is the higher order phenomenon. You first have to respect a person, then go to work on building trust.

People use the words trust, fear, respect, and vulnerability freely every day. It is rare that they stop and think about the relationships between the concepts. Thinking about and discussing these ideas ensures that communication has a common ground for understanding, so take some time in your work group to wrestle with these questions.

Hospital executives quit on the spot. Corporate giants took healthcare into their own hands. Flu hit the country hard. Nurses wanted to cut ties with Facebook. These and four other events and trends shaped the year in healthcare — and the lessons executives can take from them into 2019.

Flu-related deaths hit 40-year high

Roughly 80,000 Americans died of flu and related complications last winter, according to the CDC, along with a record-breaking estimate of 900,000 hospitalizations. That made 2017-18 the deadliest flu season since 1976, the date of the first published paper reporting total seasonal flu deaths, according to the CDC’s Kristen Nordlund.

The milestone flu season reflected a couple of trends. No. 1: Fee-for-service remains the dominant payment model in healthcare. Flu-related hospitalizations triggered financial gains for health systems and hospital networks. No. 2: A deadly flu season gave more weight to concerns about a flu pandemic, which weighs heavily on the minds of CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, and Bill Gates, among others.

JP Morgan-Berkshire Hathaway-Amazon rocks healthcare

Not even one month into 2018, three corporate giants combined forces to lower healthcare costs for 1.2 million workers. Since the Jan. 30 announcement, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase made several important hires: Surgeon, writer and policy wonk Atul Gawande, MD, started work as CEO of the health venture July 9. Soon after, Jack Stoddard, general manager for digital health at Comcast Corp., was appointed COO. More questions than answers remain about this corporate healthcare disruption, including how extensively the new entrants will redesign healthcare for their employees and how much they will collaborate with traditional healthcare providers.

While Dr. Gawande and Mr. Stoddard continue to build their healthcare-centric team to pursue an ambitious mission, remarks from a member of the old guard illustrate the frustration fueling these corporate giants’ foray into healthcare. “A lot of the medical care we do deliver is wrong — so expensive and wrong,” Charlie Munger, vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, said in a May interview with CNBC. “It’s ridiculous. A lot of our medical providers are artificially prolonging death so they can make more money.”

While someone briefed on the undertaking said the alliance does not plan to replace existing health insurers or hospitals, it will be fascinating to see how this partnership forces legacy providers to behave differently. Chief executives Jamie Dimon, Warren Buffett and Jeff Bezos are clearly dissatisfied with the way their employees’ healthcare has been accessed, delivered and priced to date.

Sudden executive resignations

The practice of two-week notice became less standard for hospital and health system leaders this year — especially CEOs. Becker’s covers roughly 100 executive moves per month, and the rate at which we wrote about executives abruptly leaving their hospitals in 2018 stood out from the norm. Executives normally provide ample notice of their departure from an organization, much more than the baseline of two weeks that’s expected for any industry or occupation. But in 2018 many more executives resigned immediately, withholding explanation for their sudden departure or bound by non-disclosures to keep it confidential. For the first time, we began publishing round-ups of executives who departed with little notice. Two months into the year, we had nearly a dozen to report.

Healthcare consistently has a high executive turnover rate — 18 percent in 2017. But 2018 was a year in which leadership churn became even more volatile with the swift and mysterious nature of executive exits. The uptick in unexplained resignations occurred during the #MeToo movement, but we don’t have the right information to draw any correlation between them. The frequency of “effective immediately” resignations will normalize this practice if it persists in 2019, which could prove detrimental to hospitals for a host of reasons. Transparency is important in healthcare; highly paid executives quietly walking away from their posts does not bode well for community affairs or physician engagement. It goes back to a lesson from media relations 101: “No comment” is the worst comment.

Health system-backed drug company receives warm welcome

Several leading health systems kicked off 2018 by uniting to create a nonprofit, independent, generic drug company named Civica Rx to fight high drug prices and chronic shortages. The pharmaceutical entrant — backed by Intermountain Healthcare, HCA Healthcare, Mayo Clinic, Catholic Health Initiatives, Providence St. Joseph Health, SSM Health and Trinity Health — is led by CEO Martin Van Trieste, former chief quality officer for biotech giant Amgen. The company’s focus will be a group of 14 generic drugs, administered to patients in hospitals, that have been in short supply and increasingly expensive in recent years. The consortium has declined to name the drugs in development, but said it expects to have its first products on the market as early as 2019.

Intermountain CEO Marc Harrison, MD, exercised measure when describing the new drug company’s mission, noting that responsible pharmaceutical companies will fair fine, but those that have been unprincipled in the past with price increases or supply issues should watch out. Civica Rx may be starting with 14 drugs, but it has noted that there are nearly 200 generics it considers essential that have experienced shortages and price hikes.

Based on reactions from providers and on The Hill, the potential for Civica Rx to quickly gain participants and policy advocates seems rich. For instance, even before Civica Rx applied to the FDA for permission to manufacture drugs, the idea of the company caught hospitals’ interest nationwide. Dr. Harrison said approximately 120 healthcare companies — representing about one-third of hospitals in the U.S. — contacted Civica Rx organizers with interest in participating. Furthermore, lawmakers and regulators were quick to throw support behind the venture even though Congress has done little to get drug pricing under control. Dr. Harrison noted to Modern Healthcare that, as of November 2018, the collaborative “received tremendous bipartisan encouragement from elected officials and from regulatory agencies to continue with our efforts.”

Guns and shootings cemented as a healthcare issue

Gun violence was never outside the realm of health and wellness, but in 2018 the medical community passionately declared the issue as one within their jurisdiction. When the National Rifle Association tweeted Nov. 7 that “Someone should tell self-important anti-gun doctors to stay in their lane,” physicians were quick to respond with detailed, graphic stories and images of their encounters treating the aftermath of gun violence. The #ThisIsOurLane social media movement coincided with tragedy Nov. 19, when a man fatally shot a physician, pharmacist and police officer in Mercy Hospital in Chicago.

With the right resources, clinicians can become ardent advocates to better patients’ social determinants of health, including responsible gun ownership and use. Leavitt Partners released poll findings in spring 2018 in which physicians said they see how social determinants influence patients’ well-being, but do not yet have the resources to help with things like housing, hunger, transportation and securing health insurance. If the fervor of #ThisIsOurLane — and attention paid to it — is any indication, physicians deeply care about nonmedical issues that affect patients’ health. With the right resources, the medical community stands to become a powerful catalyst for change for a broad range of issues.

If health systems are serious about success under value-based payment models, they will empower clinicians with the support, partnerships and tools needed to intervene and improve social determinants of health for the good of their patients.

Media coverage of surprise billing

In late 2017, the American Hospital Association released an advisory notice encouraging members to prepare for a yearlong media investigation into healthcare pricing, conducted by Vox Media Senior Correspondent Sarah Kliff. The AHA’s memo illustrated how poorly prepared hospital executives and media teams are in fielding questions about pricing, especially facility fees.

“When I have tried to conduct interviews with hospital executives about how they set their prices, I find that many are reluctant to comment,” Ms. Kliff wrote. By the end of her 15-month project, Ms. Kliff had read 1,182 ER bills from every state and wrote a dozen articles about individual patient’s financial experiences with hospitals (she was also on maternity leave from June through September). Her work produced some effective headlines. Case in point: “A baby was treated with a nap and a bottle of formula. His parents received an $18,000 bill.” In that case, the hospital reversed the family’s $15,666 trauma fee after Ms. Kliff published her report.

As of Jan. 1, Medicare requires hospitals to disclose prices publicly — but this change is unlikely to greatly benefit patients and consumers since list prices don’t reflect what insurers, government programs and patients pay. Furthermore, price transparency is but one of the problems Ms. Kliff encountered in her extensive reporting. Others include high prices for generic drug store items ($238 for eye drops that run $15 to $50 in a retail pharmacy), out-of-network physicians tending to patients who are visiting in-network hospitals, and ER facility fees. Hospitals reversed $45,107 in medical bills as a result of Ms. Kliff’s reporting. Based on the change spearheaded by her work and the Congressional attention paid to medical billing practices, hospitals and health systems shouldn’t quit their AHA-advised preparation on their own billing practices just yet. They also shouldn’t chalk much progress up to CMS-mandated price postings, because that information does not answer the questions Ms. Kliff set out to answer, including how hospital set their prices. There will only be more questions like this — from journalists, patients and lawmakers.

Optum ‘scaring the crap out of hospitals‘

Which business is keeping hospital leaders up at night? Many executives will tell you it’s not Amazon, not CVS, not One Medical — but Optum, the provider services arm of UnitedHealth Group. Optum was a key driver of the 11.7 percent gain UnitedHealth Group’s stock saw in 2018, which made it one of the top performers in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, according to Barron’s. Through its OptumCare branch, Optum employs or is affiliated with more than 30,000 physicians — roughly 8,000 more than Oakland, Calif.-based Kaiser Permanente.

Aside from directly competing for patients, Optum wants to hire or affiliate with the same MD-certified talent. It offers physicians three ways to do so: direct employment, network affiliation or practice acquisition. “OptumCare Medical Group offers recent medical school graduates the opportunity to practice medicine and become a valuable partner in their local community minus the hassles associated with the ever-changing business side of healthcare,” the company writes on its employment website.

It’s not just the physician force that makes Optum a serious concern for hospitals. Part of the challenge is that the $91 billion business has a hand in several healthcare buckets, expanding its presence as either a serious competitor/threat or a potential collaborator in multiple arenas since it is not easily categorized. For instance, consider the mountain of data Optum sits upon, with valuable insights related to utilization, costs and patient behaviors. “Because they are connected to UnitedHealth, they probably have more healthcare data than anyone on the planet,” the CEO of a $2.5 billion health system said.

Mark Zuckerberg lost face with nurses

For as much as we talk about the collision of Silicon Valley and healthcare, one of the year’s most vivid clashes came down to a dozen California nurses and Mark Zuckerberg, the chairman and CEO of Facebook and world’s third-richest person. San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center was renamed the Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center in 2015 after Mr. Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, MD, gave $75 million to the organization.

Soon after the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica ordeal came to light, a dozen nurses protested and demanded Mr. Zuckerberg’s name be stripped from their hospital. His name is hardly synonymous with the protection of privacy, they argued. But philanthropy proves to be more of an art than a science. By November, even as a San Francisco politician pressed for the removal of the name, hospital CEO Susan Ehrlich, MD, said: “We are honored that Dr. Chan and Mr. Zuckerberg thought highly enough of our hospital and staff, and the health of San Franciscans, to donate their resources to our mission.”

The dispute illustrates the tension hospital and health system executives must deal with as cash-rich tech giants and venture capitalists make more high-profile forays into healthcare. Hospitals can use the cash, sure, but the alignment of value systems may present some challenges. 2018 was a year in which several tech companies faced problems with transparency, holding leaders publicly accountable, and diversity in hiring, among other issues. A dozen nurses protesting their hospital sharing a name with Mark Zuckerberg? That’s not the last time we’ll see clinicians urging wealthy but problematic tech icons to back off. Hospital executives will need to be adept in handling that tension and exercise urgency in their response.

You’ve probably felt the battle raging within you. To hold onto your beliefs. To boldly proclaim and do what you feel is right.

The world is crying out around you to do that what they believe to be true. All the while trying to pull you to their side and strip away your integrity.

There’s a battle happening. The battle to maintain our integrity while living in a world that beckons us with the desires of others.

Months ago I wrote a blog post with quotes from Nelson Mandela. I also shared leadership quotes from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

While these posts received quite a bit of positive attention, there were also questions regarding the posts. Partially relating to maintaining your integrity while being told to tweet something one of these great men had said.

Instead of tweeting out quotes from Nelson Mandela or Martin Luther King Jr, it was suggested to take the quote, make it your own, and take action. Eventually changing the world because of the action you took.

This blew me away as I never equated asking someone to retweet a quote to losing their integrity. I thought it was a great way to remember these special men and to share some of their great insights.

After this was brought up, I can see how one could possibly begin to lose the fight to maintain integrity. If all we ever do is tweet good words and yet never act on them, what good are we? How are we really improving the world?

Those thoughts brings me to this post and the idea of maintaining our integrity while living a life true to ourselves.

So, what can be done to win the battle that wants us to lose our integrity?

Be true to yourself: First and foremost, be true to yourself. If someone asks you to retweet a quote or a link and you don’t feel it lives up to your standards or goals, don’t do it. Or if someone asks you to do something that goes against what you believe, tell them no and don’t do it.

This brings up memories of my middle school days. In 6th or 7th grade, my friends began to think it was fun to use profane words.

These guys would hang out behind the school whispering and sharing the bad words they’d learned.

One day a couple of these friends approached me and tried to influence me to curse with them. However, even at that age, I knew it would affect my integrity to do so.

When I refused to use the same words they used, they resorted to offering me cold, hard cash to do something against my beliefs. In the end, I knew what was right and what was wrong. I refused to do what was asked.

Don’t cave into the requests of others just because you follow them and they ask. You’ve got to stay true to your direction even if that means going against the request of someone else.

Be honest with others: I’m so glad a couple of readers brought up this issue with the request for tweets. This issue of integrity never crossed my mind when I asked others to retweet the quotes.

Rather, I was hoping it would inspire people. That they would see what great men have done and hope to do the same.

With this honest reply, I was able to see not everyone sees this in the same light. It also helped me realize people react to requests in different ways.

Honesty opens up the eyes of others and allows you to be true to yourself.

Be aware of your choices: Robert Brault once said

“You do not wake up one morning a bad person. It happens by a thousand tiny surrenders of self-respect to self-interest.”

Each choice you make has an effect on your integrity. You either make choices that add to your integrity or choices to surrender and lose the integrity you hold so dear.

Learn to examine the choices laid before you. Decide whether or not they add to your integrity. Make the choices that will make you a person of integrity.

Integrity can be an easy thing to lose. It can also be an easy thing to maintain when we’re aware of the actions we can take to keep it.

I know you want to live a life of integrity. I encourage you to do so.

Remember, be true to yourself, be honest with others, and know the choices you make affect your integrity.

Question: How do you maintain your integrity?

But because someone says truth is relative, does it make it so? No, and you know this.

Look at the grass outside of your office window. What color is it? There’s typically only two answers to this question:

The grass is green.

The grass is brown.

One is a sign of healthy grass. The other is a sign of dead grass. Yet there’s typically only two colors of grass.

Now, if you looked out your window and saw a lawn full of green grass and someone told you the grass was pink, what would you do? You’d probably laugh. I know I would.

You wouldn’t coddle the person and tell them they’re right. After laughing, you’d probably correct them. You’d tell them: Sam, the grass isn’t pink. The grass is green.

The truth is the grass is green. There’s no two ways about it.

You cannot change the fact that the grass in front of you is green. It is what it is. And grass being the color green is the truth.

You can try to twist the truth of the grass’ color as much as you would like. Your twisting of the colors wouldn’t change the truth.

But how often do we try to twist the truth when it comes to our businesses, organizations, or relationships? We try to twist the truth to what suits our desires, needs, or wants.

And still, no twisting of those truths makes our lies in business any less wrong.

There’s a reason truth matters. Truth is a guiding compass for what is right and what is wrong. You can look at the truth and know whether or not what you’re doing is right.

Truth allows you to know true north. It allows you to get to the destination you’re heading. And it helps you accomplish this with integrity.

Be careful of twisting truths to fit your narrative. It’s a dangerous path to go down.

The more you twist the truth, the more you’ll be willing to do the next wrong thing. Then the next. And then another…

But if you stay on the straight and narrow… If you’re willing to stand for truth… If you’re willing to say truth matters…

You’ll have an unshakeable character. You’ll earn the respect of others. And you’ll know you did the right thing.

I hope you’re not living in a state of relative truth. I hope and pray you’re living a life of truth.

Have enough beds? Demographic trends paint an alarming picture

Healthcare providers know that inpatient volumes are down over historic levels. (But let’s not talk […]

Healthcare providers know that inpatient volumes are down over historic levels. (But let’s not talk about emergency department volumes—those are WAY up.) They know this trend originates mostly with Medicare beneficiaries. They also know the causes: migration to outpatient services, observation day rules, intense focus on decreasing length of stay, and reduced readmissions as part of their quality initiatives.

What they may miss, however, is that this trend also has something to do with the declining average age of our nation’s senior population—a phenomenon that first began in 2005 and will continue until about 2020. In 2005, the average age of our nation’s senior population was 75.2 years; in 2020, the average age is expected to be 74.4 years.

This fact is important because older seniors consume significantly greater healthcare resources than younger seniors. Today, those over 65 represent about 15 percent of the total U.S. population. By 2020, one out of six Americans will be 65 or older, rising to 22 percent by 2040. Understanding how this population is distributed among age cohorts is critically important not only in understanding current trends in reduced utilization, but also in preparing for the future.

Taking a Closer Look

This increasing proportion of the population that are seniors is important because the average Medicare beneficiary consumes about four times the hospital-based services as the average commercially insured person. But it is just as important to look more closely at consumption patterns within the senior population. Those between ages 75 and 84 consume about 60 percent more services than seniors ages 65 to 74. Those age 85 and above consume about two-and-a-half times as much.

According to U.S. Census forecasts, in 2021, the over-75 population will make up the lowest percentage of the senior Medicare population in recent history, at about 41 percent. By 2040, seniors older than 75 will constitute 55 percent of the total senior population. This fact alone would suggest that we are in for a reversal of declining volume patterns—but by how much?

The answer is that if nothing is done to further reduce admissions and days per 1,000 for the senior Medicare population, inpatient days should almost double from about 70 million today to about 130 million in 2040 on the basis of demographic changes alone. That represents a need for some 220,000 additional beds at 75 percent capacity by 2040—never mind all the other healthcare services that will be needed. But even as there is general recognition among healthcare leaders of the advent of an aging population, there is also the general sense that somehow, we will not need the same level of resources to meet that demand as we do today.

Where does that sense of assurance come from? Apparently, it stems from the belief that unnecessary and excess utilization exists purely due to financial reasons, and that even more of the care delivered on an inpatient basis could be performed on an outpatient basis or at home with better monitoring and intervention through new technologies. But there also appears to be an ignoring of the well-known trend for the population becoming increasingly co-morbid at ever-younger ages. Additionally, some believe that increased focus on addressing social determinants of health, which impact 64 percent of health outcomes, will reduce need for medical services.

All of these assumptions may be true, in theory. In practice, however, as a senior healthcare executive and registered nurse said to me recently, “People are really sick. You have no idea.” There is also the enormous question of how one staffs and gets paid for programs and investments that might reduce demand for hospital-based services. The economics of today’s medicalized approach to health care is unprepared to address this.

A Critical Issue for Leadership

This is an issue that should be of paramount importance to healthcare providers. As seniors comprise a greater portion of our population, demand for inpatient and post-acute services will significantly increase. The hope and dream expressed in the view that hospital-based utilization might be reduced springs from a terrible reality: Hospitals in general, with the possible exception of high-end tertiary/quaternary services, lose money on government-reimbursed volume—and this will only get worse as cost inflation continues to exceed government reimbursement trends.

The prospect of the demand for inpatient days nearly doubling over the next 20 years paints a horrifying financial picture. Who, then, would not want to hope that something magical will happen to prevent a scenario that logic and data tell us is likely to occur?

It’s time for healthcare leaders to take a hard look at the trends around senior aging and have tough discussions with their executive teams and boards about the impact these trends could have on their organizations’ futures—and what they should be doing now to prepare.

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time — none. Zero.”

— Charlie Munger, Self-made billionaire & Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner

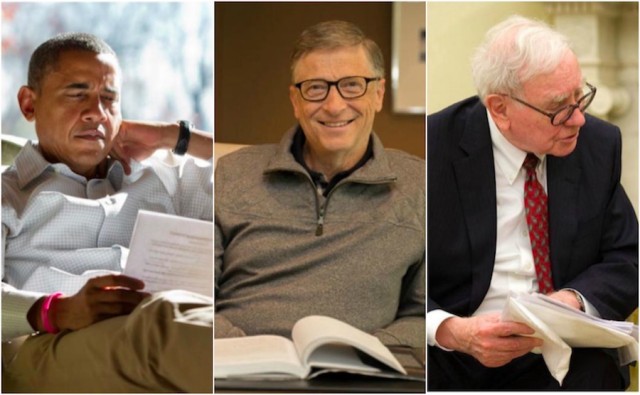

Why did the busiest person in the world, former president Barack Obama, read an hour a day while in office?

Why has the best investor in history, Warren Buffett, invested 80% of his time in reading and thinking throughout his career?

Why has the world’s richest person, Bill Gates, read a book a week during his career? And why has he taken a yearly two-week reading vacation throughout his entire career?

Why do the world’s smartest and busiest people find one hour a day for deliberate learning (the 5-hour rule), while others make excuses about how busy they are?

What do they see that others don’t?

The answer is simple: Learning is the single best investment of our time that we can make. Or as Benjamin Franklin said, “An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”

This insight is fundamental to succeeding in our knowledge economy, yet few people realize it. Luckily, once you do understand the value of knowledge, it’s simple to get more of it. Just dedicate yourself to constant learning.

“Intellectual capital will always trump financial capital.” — Paul Tudor Jones, self-made billionaire entrepreneur, investor, and philanthropist

We spend our lives collecting, spending, lusting after, and worrying about money — in fact, when we say we “don’t have time” to learn something new, it’s usually because we are feverishly devoting our time to earning money, but something is happening right now that’s changing the relationship between money and knowledge.

We are at the beginning of a period of what renowned futurist Peter Diamandis calls rapid demonetization, in which technology is rendering previously expensive products or services much cheaper — or even free.

This chart from Diamandis’ book Abundance shows how we’ve demonetized $900,000 worth of products and services you might have purchased between 1969 and 1989.

This demonetization will accelerate in the future. Automated vehicle fleets will eliminate one of our biggest purchases: a car. Virtual reality will make expensive experiences, such as going to a concert or playing golf, instantly available at much lower cost. While the difference between reality and virtual reality is almost incomparable at the moment, the rate of improvement of VR is exponential.

While education and health care costs have risen, innovation in these fields will likely lead to eventual demonetization as well. Many higher educational institutions, for example, have legacy costs to support multiple layers of hierarchy and to upkeep their campuses. Newer institutions are finding ways to dramatically lower costs by offering their services exclusively online, focusing only on training for in-demand, high-paying skills, or having employers who recruit students subsidize the cost of tuition.

Finally, new devices and technologies, such as CRISPR, the XPrize Tricorder, better diagnostics via artificial intelligence, and reduced cost of genomic sequencing will revolutionize the healthcare system. These technologies and other ones like them will dramatically lower the average cost of healthcare by focusing on prevention rather than cure and management.

While goods and services are becoming demonetized, knowledge is becoming increasingly valuable.

“The central event of the twentieth century is the overthrow of matter. In technology, economics, and the politics of nations, wealth in the form of physical resources is steadily declining in value and significance. The powers of mind are everywhere ascendant over the brute force of things.” —George Gilder (technology thinker)

Perhaps the best example of the rising value of certain forms of knowledge is the self-driving car industry. Sebastian Thrun, founder of Google X and Google’s self-driving car team, gives the example of Uber paying $700 million for Otto, a six-month-old company with 70 employees, and of GM spending $1 billion on their acquisition of Cruise. He concludes that in this industry, “The going rate for talent these days is $10 million.”

That’s $10 million per skilled worker, and while that’s the most stunning example, it’s not just true for incredibly rare and lucrative technical skills. People who identify skills needed for future jobs — e.g., data analyst, product designer, physical therapist — and quickly learn them are poised to win.

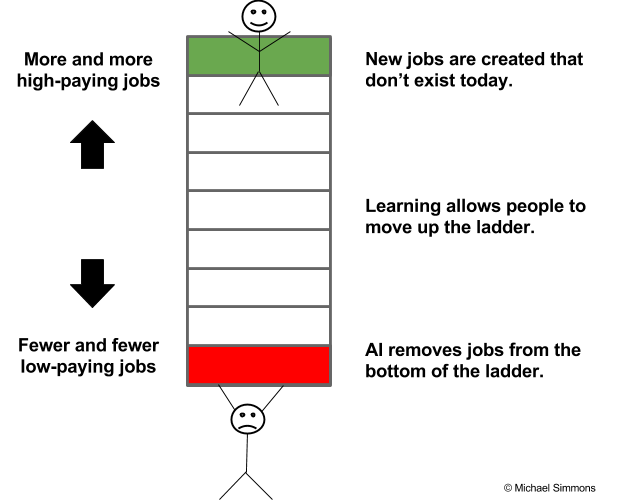

Those who work really hard throughout their career but don’t take time out of their schedule to constantly learn will be the new “at-risk” group. They risk remaining stuck on the bottom rung of global competition, and they risk losing their jobs to automation, just as blue-collar workers did between 2000 and 2010 when robots replaced 85 percent of manufacturing jobs.

Why?

People at the bottom of the economic ladder are being squeezed more and compensated less, while those at the top have more opportunities and are paid more than ever before. The irony is that the problem isn’t a lack of jobs. Rather, it’s a lack of people with the right skills and knowledge to fill the jobs.

An Atlantic article captures the paradox: “Employers across industries and regions have complained for years about a lack of skilled workers, and their complaints are borne out in U.S. employment data. In July [2015], the number of job postings reached its highest level ever, at 5.8 million, and the unemployment rate was comfortably below the post-World War II average. But, at the same time, over 17 million Americans are either unemployed, not working but interested in finding work, or doing part-time work but aspiring to full-time work.”

In short, we can see how at a fundamental level knowledge is gradually becoming its own important and unique form of currency. In other words, knowledge is the new money. Similar to money, knowledge often serves as a medium of exchange and store of value.

But, unlike money, when you use knowledge or give it away, you don’t lose it. In fact, it’s the opposite. The more you give away knowledge, the more you:

Transferring knowledge anywhere in the world is free and instant. Its value compounds over time faster than money. It can be converted into many things, including things that money can’t buy, such as authentic relationships and high levels of subjective well-being. It helps you accomplish your goals faster and better. It’s fun to acquire. It makes your brain work better. It expands your vocabulary, making you a better communicator. It helps you think bigger and beyond your circumstances. It connects you to communities of people you didn’t even know existed. It puts your life in perspective by essentially helping you live many lives in one life through other people’s experiences and wisdom.

Former President Obama perfectly explains why he was so committed to reading during his Presidency in a recent New York Times interview:

“At a time when events move so quickly and so much information is transmitted,” he said, reading gave him the ability to occasionally “slow down and get perspective” and “the ability to get in somebody else’s shoes.” These two things, he added, “have been invaluable to me. Whether they’ve made me a better president I can’t say. But what I can say is that they have allowed me to sort of maintain my balance during the course of eight years, because this is a place that comes at you hard and fast and doesn’t let up.”

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” — Alvin Toffler

So, how do we learn the right knowledge and have it pay off for us? The six points below serve as a framework to help you begin to answer this question. I also created an in-depth webinar on Learning How To Learn that you can watch for free.

To shift our focus from being overly obsessed with money to a more savvy and realistic quest for knowledge, we need to stop thinking that we only acquire knowledge from 5 to 22 years old, and that then we can get a job and mentally coast through the rest of our lives if we work hard. To survive and thrive in this new era, we must constantly learn.

Working hard is the industrial era approach to getting ahead. Learning hard is the knowledge economy equivalent.

Just as we have minimum recommended dosages of vitamins, steps per day, and minutes of aerobic exercise for maintaining physical health, we need to be rigorous about the minimum dose of deliberate learning that will maintain our economic health. The long-term effects of intellectual complacency are just as insidious as the long-term effects of not exercising, eating well, or sleeping enough. Not learning at least 5 hours per week (the 5-hour rule) is the smoking of the 21st century and this article is the warning label.

Don’t be lazy. Don’t make excuses. Just get it done.

“Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever.” — Mahatma Gandhi

Before his daughter was born, successful entrepreneur Ben Clarke focused on deliberate learning every day from 6:45 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. for five years (2,000+ hours), but when his daughter was born, he decided to replace his learning time with daddy-daughter time. This is the point at which most people would give up on their learning ritual.

Instead of doing that, Ben decided to change his daily work schedule. He shortened the number of hours he worked on his to do list in order to make room for his learning ritual. Keep in mind that Ben oversees 200+ employees at his company, The Shipyard, and is always busy. In his words, “By working less and learning more, I might seem to get less done in a day, but I get dramatically more done in my year and in my career.” This wasn’t an easy decision by any means, but it reflects the type of difficult decisions that we all need to start making. Even if you’re just an entry-level employee, there’s no excuse. You can find mini learning periods during your downtimes (commutes, lunch breaks, slow times). Even 15 minutes per day will add up to nearly 100 hours over a year. Time and energy should not be excuses. Rather, they are difficult, but overcomable challenges. By being one of the few people who rises to this challenge, you reap that much more in reward.

We often believe we can’t afford the time it takes, but the opposite is true: None of us can afford not to learn.

Learning is no longer a luxury; it’s a necessity.

The busiest, most successful people in the world find at least an hour to learn EVERY DAY. So can you!

Just three steps are needed to create your own learning ritual:

Over the last three years, I’ve researched how top performers find the time, stay consistent, and get more results. There was too much information for one article, so I spent dozens of hours and created a free masterclass to help you master your learning ritual too!

This article sets out seven thoughts on healthcare systems.

The article discusses:

Before starting the core of the article, we note two thoughts. First, we view a core strategy of systems to spend a great percentage of their time on those things that currently work and bring in profits and revenues. As a general rule, we advise systems to spend 70 to 80 percent of their time doubling down on what works (i.e., their core strengths) and 20 to 30 percent of their time on new efforts.

Second, when we talk about healthcare as a zero-sum game, we mean the total increases in healthcare spend are slowing down and there are greater threats to the hospital portion of that spend. I.e., the pie is growing at a slower pace and profits in the hospital sector are decreasing.

I. Types of Healthcare Systems

We generally see six to eight types of healthcare systems. There is some overlap, with some organizations falling into several types.

1. Elite Systems. These systems generally make U.S. News & World Report’s annual “Best Hospitals” ranking. These are systems like Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins Hospital, NewYork-Presbyterian, Massachusetts General, UPMC and a number of others. These systems are often academic medical centers or teaching hospitals.

2. Regionally Dominant Systems. These systems are very strong in their geographic area. The core concept behind these systems has been to make them so good and so important that payers and patients can’t easily go around them. Generally, this market position allows systems to generate slightly higher prices, which are important to their longevity and profitability.

3. Kaiser Permanente. A third type of system is Oakland-based Kaiser Permanente itself. We view Kaiser as a type in and of itself since it is both so large and completely vertically integrated with Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Kaiser Foundation Hospitals and Permanente Medical Groups. Kaiser was established as a company looking to control healthcare costs for construction, shipyard and steel mill workers for the Kaiser industrial companies in the late 1930s and 1940s. As companies like Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase try to reduce costs, it is worth noting that they are copying Kaiser’s purpose but not building hospitals. However, they are after the same goal that Kaiser originally sought. Making Kaiser even more interesting is its ability to take advantage of remote and virtual care as a mechanism to lower costs and expand access to care.

4. Community Hospitals. Community hospitals is an umbrella term for smaller hospital systems or hospitals. They can be suburban, rural or urban. Community hospitals are often associated with rural or suburban markets, but large cities can contain community hospitals if they serve a market segment distinct from a major tertiary care center. Community hospitals are typically one- to three-hospital systems often characterized by relatively limited resources. For purposes of this article, community hospitals are not classified as teaching hospitals — meaning they have minimal intern- and resident-per-bed ratios and involvement in GME programs.

5. Safety-Net Hospitals. When we think of safety-net hospitals, we typically recall hospitals that truly function as safety nets in their communities by treating the most medically vulnerable populations, including Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured. These organizations receive a great percentage of revenue from Medicaid, supplemental government payments and self-paying patients. Overall, they have very little commercial business. Safety-net hospitals exist in different areas, urban or rural. Many of the other types of systems noted in this article may also be considered safety-net systems.

6. National Chains. We divide national chains largely based on how their market position has developed. National chains that have developed markets and are dominant in them tend to be more successful. Chains tend to be less successful when they are largely developed out of disparate health systems and don’t possess a lot of market clout in certain areas.

7. Specialty Hospitals. These are typically orthopedic hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, women’s hospitals, children’s hospital or other types of hospitals that specialize in a field of medicine or have a very specific purpose.

II. Mergers and Acquisitions

There have seen several large mergers over the last few years, including those of Aurora-Advocate, Baylor Scott & White-Memorial Hermann, CHI-Dignity and Mercy-Bon Secours, among others.

In evaluating a merger, the No. 1 question we ask is, “Is there a clear and compelling reason or purpose for the merger?” This is the quintessential discussion piece around a merger. The types of compelling reasons often come in one of several varieties. First: Is the merger intended to double down and create greater market strength? In other words, will the merger make a system regionally dominant or more dominant?

Second: Does the merger make the system better capitalized and able to make more investments that it otherwise could not make? For example, a large number of community hospitals don’t have the finances to invest in the health IT they need, the business and practices they need, the labor they need or other initiatives.

Third: Does the merger allow the amortization of central costs? Due to a variety of political reasons, many systems have a hard time taking advantage of the amortization of costs that would otherwise come from either reducing numbers of locations or reducing some of the administrative leadership.

Finally, fourth: Does the merger make the system less fragile?

Each of these four questions tie back to the core query: Does the merger have a compelling reason or not?

III. Headwinds

Hospitals face many different headwinds. This goes into the concept of healthcare as a zero-sum game. There is only so much pie to be shared, and the hospital slice of pie is being attacked or threatened in various areas. Certain headwinds include:

1. Pharma Costs. The increasing cost of pharmaceuticals and the inability to control this cost particularly in the non-generic area. Here, increasingly the one cost area that payers are trying to merge with relates to pharma/PBM the one cost that hospitals can’t seem to control is pharma costs. There is little wonder there is so much attention paid to pharma costs in D.C.

2. Labor Costs. Notwithstanding all the discussions of technology and saving healthcare through technology, healthcare is often a labor-intensive business. Human care, especially as the population ages, requires lots of people — and people are expensive.

3. Bricks and Mortar. Most systems have extensive real estate costs. Hospitals that have tried to win the competitive game by owning more sites on the map find it is very expensive to maintain lots of sites.

4. Slowing Rises in Reimbursement – Federal and Commercial. Increasingly, due to federal and state financial issues, governments (and interest by employers) have less ability to keep raising healthcare prices. Instead, there is greater movement toward softer increases or reduced reimbursement.

5. Lower Commercial Mix. Most hospitals and health systems do better when their payer mix contains a higher percentage of commercial business versus Medicare or Medicaid. In essence, the greater percentage of commercial business, the better a health system does. Hospital executives have traditionally talked about their commercial business subsidizing the Medicare/Medicaid business. As the population ages and as companies get more aggressive about managing their own healthcare costs, you see a shift — even if just a few percentage points — to a higher percentage of Medicare/Medicaid business. There is serious potential for this to impact the long-term profitability of hospitals and health systems. Big companies like JPMorgan, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and some other giants like Google and Apple are first and foremost seeking to control their own healthcare costs. This often means steering certain types of business toward narrow networks, which can translate to less commercial business for hospitals.

6. Cybersecurity and Health IT Costs. Most systems could spend their entire budgets on cybersecurity if they wanted to. That’s impossible, of course, but the potential costs of a security breach or incident loom large and there are only so many dollars to cover these costs.

7. The Loss of Ancillary Income. Health systems traditionally relied on a handful of key specialties —cardiology, orthopedics, spine and oncology, for example — and ancillaries like imaging, labs, radiation therapy and others to make a good deal of their profits. Now ancillaries are increasingly shifted away from systems toward for-profits and other providers. For example, Quest Diagnostics and Laboratory Corporation of America have aggressively expanded their market share in the diagnostic lab industry by acquiring labs from health systems or striking management partnerships for diagnostic services.

8. Payers Less Reliant on Systems. Payers have signaled less reliance on hospitals and health systems. This headwind is indicated in a couple of trends. One is payers increasingly buying outpatient providers and investing in many other types of providers. Another is payers looking to merge with pharmaceutical providers or pharmacy and benefit managers.

9. Supergroups. Increasingly in certain specialties and multispecialty groups, especially orthopedics and a couple other specialties, there is an effort to develop strong “super groups.” The idea of some of these super groups is to work toward managing the top line of costs, then dole out and subcontract the other costs. Again, this could potentially move hospitals further and further downstream as cost centers instead of leaders.

IV. The Great Fear

The great fear of health systems is really twofold. First: that more and more systems end up in bankruptcy because they just can’t make the margins they need. We usually see this unfold with smaller hospitals, but over the last 20 years, we have seen bankruptcies periodically affect big hospital systems as well. (Here are 14 hospitals that have filed for bankruptcy in 2018 to date. According to data compiled by Bloomberg, at least 26 nonprofit hospitals across the nation are already in default or distress.)

Second, and more likely, is that hospitals in general become more like mid-level safety net systems for certain types of care — with the best business moving away. I.e., as margins slide, hospitals will handle more and more of the essential types of care. This is problematic, in that many hospitals and health systems have infrastructures that were built to provide care for a wide range of patient needs. The counterpoint to these two great fears is that there is a massive need for healthcare and healthcare is expensive. In essence, there are 325,700,000 people in the United States, and it’s not easy to provide care for an aging population.

V. The Last 10 Years – What Worked

What has worked over the last five to 10 years is some mix of the following:

VI. The Next 10 Years

Over the next 10 years, we advise systems to consider the following.

VII. Other Issues

Other issues we find fascinating today are as follows.

1. First, payers are more likely to look at pharma and pharma benefit companies as merger partners than health systems. We think this is a fascinating change that reflects a few things, including the role and costs of pharmaceuticals in our country, the slowly lessening importance of health systems, and payers’ disinterest in carrying the costs of hospitals.

2. Second, for many years everyone wanted to be Kaiser. What’s fascinating today is how Kaiser now worries about Amazon, Apple and other companies that are doing what Kaiser did 50 to 100 years ago. In essence, large companies’ strategies to design their own health systems, networks or clinics to reduce healthcare costs and provide better care is a force that once created legacy systems like Kaiser and now threatens those same systems.

3. Third, we find politicians are largely tone deaf. On one side of the table is a call for a national single payer system, which at least in other countries of large size has not been a great answer and is very expensive. On the other hand, you still have politicians on the right saying just “let the free market work.” This reminds me of people who held up posters saying, “Get the government out of my Medicare.” We seem to be past a true and pure free market in healthcare. There is some place between these two extremes that probably works, and there is probably a need for some sort of public option.

4. Fourth, care navigation in many elite systems is still a debacle. There is still a lot of room for improvement in this area, but unfortunately, it is not an area that payers directly tend to pay for.

5. Fifth, we periodically hear speakers say “this app is the answer” to every problem. I contrast that by watching care given to elderly patients, and I think the app is unlikely to solve that much. It is not that there is not room for lots of apps and changes in healthcare — because there is. However, healthcare remains as a great mix of technology and a labor- and care-intensive business.