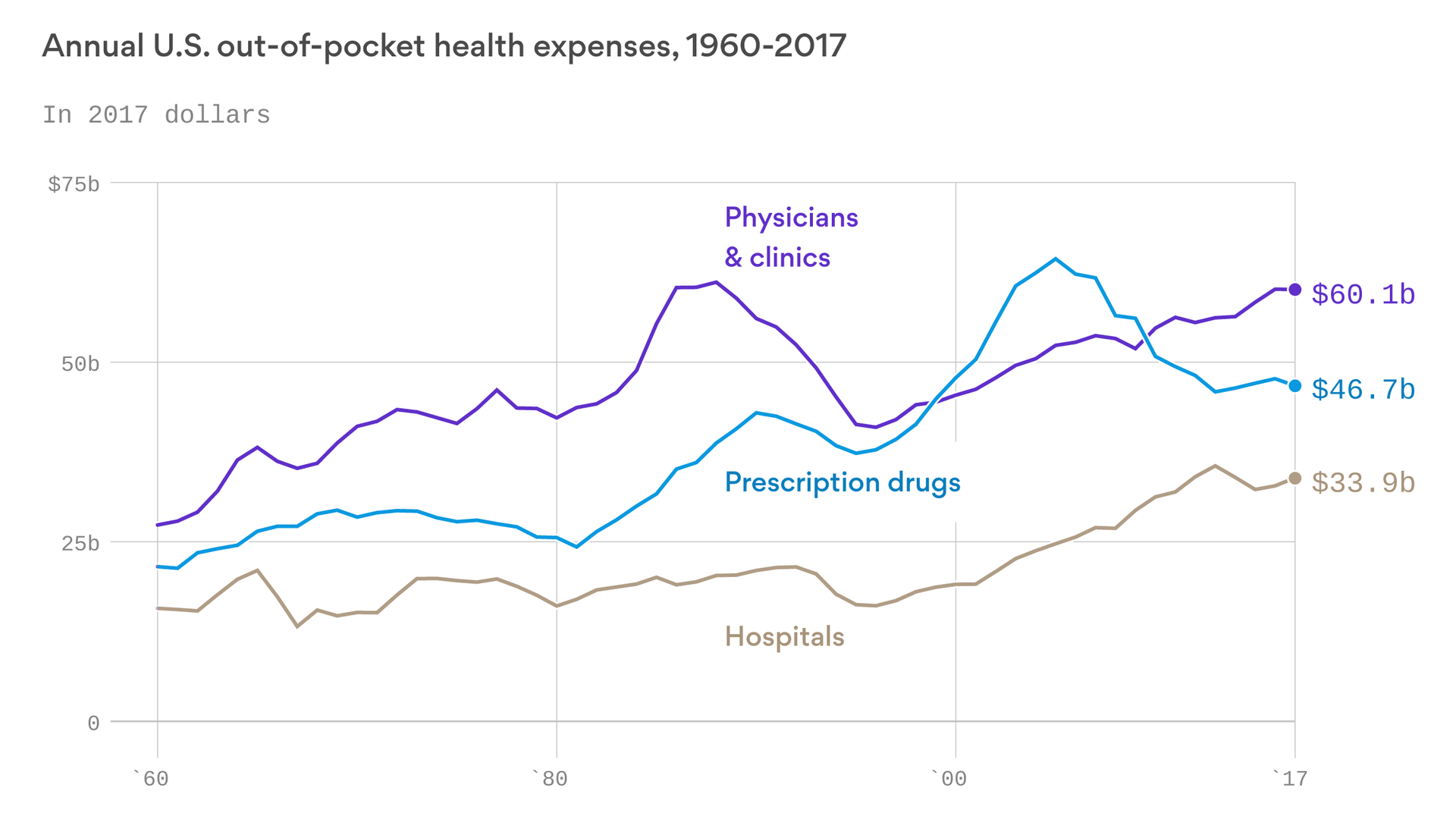

What happens when record increases in health insurance premiums and deductibles put too much stress on patients’ pocketbooks? They delay needed care out of fear they’ll be unable to shoulder an unexpected medical expense for themselves or their families.

Now more than ever, patients worry about their ability to cover out-of-pocket healthcare costs, a recent Commonwealth Fund survey shows. The percentage of patients who believe they could afford the care they need is falling, and many say satisfying their financial obligations for care has become more difficult.

But these data only tell part of the story. Our own research shows that while 68% of patients want to discuss financing options that could ease their minds about mounting healthcare expenses, providers are falling short—and families, especially, are feeling the pinch.

Feeling the pinch

According to our survey, 27% of households with children are likely to delay care because they can’t afford to pay for it. Families are also less likely to pay their out-of-pocket costs for care in full—and their chances of having their account sent to collections are twice as high.

It’s not that families and individuals don’t want to cover their out-of-pocket costs. In fact, half of the patients surveyed were willing to select providers based on the availability of financing plans that stretch out their obligation into more manageable monthly payments. The trouble is, providers have been slow to adopt flexible payment plans. They are even slower to discuss financing options with patients or publicize them more broadly.

It’s time for a new approach to patient billing—one that takes into account patients’ desire to fulfill their financial obligations for care, addresses their concerns from the point of service, and demonstrates a willingness to meet them where they are.

The experience of one new mother in Florida illustrates the gains hospitals can make when they take a compassionate approach to patient collections. As she prepared to give birth to her daughter, she found herself facing a financial dilemma. The hospital required her to “reserve” her spot in its labor and delivery unit—for a $1,000 deposit. With no money in reserve and a baby on the way, she feared she wouldn’t be able to deliver her baby at the hospital.

She asked hospital representatives whether the hospital might consider a payment plan instead of a lump-sum payment. To her relief, the hospital allowed her to extend the payment over 12 months—interest-free. It’s an option that relieved the stress of the financial burden of care during what should be a joyous time for her family.

Making a difference through flexible payments

Offsetting the impact of out-of-pocket medical costs for individuals and families doesn’t require an overhaul of a hospital’s patient financial services program. Instead, hospitals can take simple steps to help patients more easily fulfill their financial obligations for care—and reduce their costs to collect as well as bad debt in the process.

Consider offering a variety of options for payment, such as low-interest and no-interest loans that all patients qualify for, without the fear of credit reporting or negative consequences. Setting the program up so that patients have a choice and opt into the program significantly helps the patient experience. Discuss their estimated out-of-pocket expense with patients before or at the point of care, and share information on payment plans widely, both onsite and online. Lastly, a program that is consumer friendly with easy ways to pay their bills and manage their accounts will go a long way to increase patient satisfaction.

Taking a more proactive approach to affordability is not only the right thing to do for patients but also the smart choice in protecting an organization’s long-term financial health.